Recent features

Why we should stop banging on about Thatcher and the Toxteth Bloody Riots

Journalists arrive in Liverpool to tell the same story over and over again - the city cast as the lead in a Shakespearean morality play, fuelled by righteous anger, touched by tragedy, let down by treachery. Yet is our own obsession with the 1980s feeding the media stereotypes?

Paul Bryan

My personal experience of the 1981 Toxteth Riots existed, as for so many others in Liverpool, solely on television. The nightly news reports showed lines of police officers cowering under shields as youths hurled stones and set light to cars and buildings. I didn’t know why it was happening but I knew it was exciting and so did my friends – as if through some mechanism of the collective unconscious we quickly turned it into a street game, unimaginatively called ‘Toxteth Riots’. The rules were fairly simple. All you had to do was clutch a metal bin lid and defend yourself from rocks and stones hurled somewhat half-heartedly by your mates. The winner was the one who could stick it out for the longest. Writing about this now, I’ve only just realised, we were instinctively putting ourselves in the shoes of the police. They at least seemed understandable. Still, it didn’t hold our attention for long. We got bored of it after two nights.

If only I could say the same about the national media. 41 years later and they’re still using the Toxteth Riots as the go-to framing device for just about any story on Liverpool. Of course, in no way do I mean to belittle the experiences of those who were there, or those who suffered under the social forces that made life more difficult. But for me growing up, the riots always felt like something distant, from some other Liverpool, far off and largely irrelevant. If anything, the Toxteth Riots were a boon – they gave me the chance to meet TV scarecrow, Worzel Gummidge at the International Garden Festival three years later, thanks to the intervention of Michael Heseltine, unofficially crowned the Minister for Merseyside.

I mention this personal story because I’ve noticed a tendency in the media and in political circles to describe Liverpool as a single unit, with a single, monolithic outlook and I find this approach unhealthy and untrue. The Toxteth Riots as history and metaphor have become something of an unquestionable foundation stone in our understanding of Liverpool’s journey. I’m not for one minute doubting their significance, but merely wish to flag that, due to the vicarious nature in which they were experienced by many, the events will never speak to us all in the same way and I think that’s worth acknowledging given the sometimes over-simplified, stripped-down caricature of ‘Scouse’ tales that we are often encouraged to identify with. And if that applies to someone who was alive at the time, you can bet it will apply even more to those who were as yet unborn.

The Toxteth Riots sit as the starting point of a master narrative that is told and retold ad finitum. Typically, it’s a story pitched as one of strife and rebirth – a city on its knees rising phoenix-like from the ashes with the regeneration that followed. Either that or it’s used to evidence our home town’s long history of racial inequality. There are further beats in the story of course and usually they point to ‘basket-case’ – a city that just can’t seem to catch a break or get its house in order. A place that is frankly perplexing. Journalists visiting Liverpool tell the same story, time after time, yet they never tire of it, new facts on the ground serving merely to embellish an already familiar pattern.

It would be easy to point the finger at outsiders here, but this game plays out amongst Liverpool’s inhabitants too and I’ve begun to wonder… does the incessant focus on the 1980s (and we must throw the hate figure that is Margaret Thatcher into the same pot) does the constant repetition serve the city’s best interests? Do these references still yield insight or are they just a reheating of old battles, about as useful to understanding Liverpool today as the Suez crisis is to making sense of Britain’s contemporary approach to foreign policy?

A case in point. This week, the Mayor of Liverpool, Joanne Anderson was interviewed by a journalist from the left-leaning New Statesman magazine, enticed no doubt by the city’s hosting of the Labour Party Conference. Ostensibly about Liverpool’s current political crisis, the article began like this… “In 1981, the violent arrest of a young black man near Granby Street in Toxteth, Liverpool, led to nine days of rioting.”

“Journalists visiting Liverpool tell the same story, time after time, yet they never tire of it, new facts on the ground serving merely to embellish an already familiar pattern.”

What followed was a tick list from the unofficial media guide to Liverpool which we presume is handed out by the NCTJ on journalism graduation day. Margaret Thatcher, ‘managed decline’, European Capital of Culture and the regeneration of the Albert Dock, Derek “Degsy” Hatton and the Militant Tendency, gang warfare and the shootings of young children, now sadly updated with new names. Welcome to Fleet Street’s version of Punxsutawney where we’re all doomed to live the same day, every day. Bill Murray, at least, found a way out. In Liverpool, we’re still looking.

Truth is, the story could have been about anything – crime, the opening of an arts festival, or an important football match and it could have been published anywhere – The Telegraph, The Guardian, The New York Times or Unherd. It doesn’t really matter what the initial prompt is, as long as the story stays the same. Liverpool, the city, is perennially cast as the troubled lead in a Shakespearean morality play, fuelled by righteous anger, touched by tragedy, let down by treachery, now sadly a watchword for – (insert your favoured macro-political, agenda-driven blank here).

Refreshingly, the Mayor was not too impressed with the New Statesman article. On Twitter, Joanne claimed the writer had “focused on a whole load of scouse stereotypes” and accused him of “lazy journalism”. I found myself in agreement so I reached out to the Mayor for further comment, and to my surprise she replied. What she had to say, for a local Labour leader is, I think, important and worth hearing. But you’ll have to wait a while. You see, first I have this theory and it involves turning our attention inwards. It’s the real meat in this piece. For as much as we might want to blame the media, I believe that the press are, in large part, reflecting back what we as a city put out about ourselves.

Sometimes, our own worst enemy

Compare these two statements. The first is by a journalist, Oliver Brown, Chief Sports Writer at the Telegraph, who was writing about Liverpool’s complex relationship with the establishment in light of some fans failing to observe a minute’s silence to mark the death of the Queen.

“Liverpool is a city that feels that it has been shunted to the margins of British society. It is scarcely an unfounded view.”

The second is from Kim Johnson, MP for Liverpool Riverside who was describing her sense of betrayal at Labour Leader, Keir Starmer writing in the Sun in 2021.

“We are the Socialist republic of Liverpool, a city that marches to the beat of a different drum, a resilient city that will always come back fighting. But we have a long memory and will not forget this betrayal by the leader of the Labour Party, in our Labour city.”

Can you spot the similarities? For starters, they are both quite careless in their use of the collective – back to that sense of the monolithic, singular opinion to represent the Liverpool way. But they also both spoke to something else – a powerful sense of grievance baked into the city identity. Kim Johnson’s quote in particular was the perfect crystallisation of a view that has become increasingly noisy in recent years – the idea that Liverpool is ‘Scouse, not English’ – a place apart, waged in a perpetual battle to get a fair deal, coalescing around some sense of the ‘Other’.

A few weeks back, the Liverpool Echo’s Dan Haygarth, in a quite remarkable article, attempted to explain why so many in the city reject national identity. As explanations go it was comprehensive, yet strangely unconvincing, but it was a perfect reflection of what passes for common sense around here. Supposedly, our 19th-century Irish roots had turned us into ‘rebels’ sceptical of authority; our coastal location transformed us into natural internationalists who looked out rather than in; a history of being ‘let down by the establishment’ first by the Thatcher government in the 1980s and then over the Hillsborough disaster had for many ‘broken the city’s relationship with England beyond repair.’ Throw in the generosity of EU European Objective 1 funding followed by savage post-2010 cuts from Westminster, a Brexit vote that went the wrong way and a nasty article in the Spectator under Boris Johnson’s watch and a seemingly irresistible case was made for a city destined to walk alone.

Haygarth’s article concludes – “The phrase 'Scouse, not English' not only encapsulates Liverpool's civic pride and a healthy rebellious spirit, but expresses a feeling that the city has been so often let down by the establishment of this country. It should come as no shock that large swathes of this Labour-voting, outward-looking, and heavily-Irish city do not feel like they have much in common with the rest of England.”

“They also both spoke to something else – a powerful sense of grievance baked into the city identity… a mutual connection made through the collective swallowing of bitter pills… our loudest voices complicit in the forging of our own myth of alienation.”

For me, the sense of our loudest voices being complicit in the forging of our own myth of alienation is palpable and the justifications horribly deterministic. Who here thinks their life choices and personality are determined by people born 200 years ago? Stitching together disparate events, our public figures and opinion-formers are consciously weaving a narrative that seems to share some of the features of an accelerated national story – one encompassing communal loss and betrayal, a unique sense of difference forged through a mythic connection to lands beyond the horizon and an othering from a surrounding horde of distinctly unsympathetic barbarians. But as foundation stories go, it seems to lack many of the positive elements that make nationhood worth having – with little sense of victories past or historic purpose hard won. Today, it’s hard to look back to our past days as the Second City of Empire with any pride – our fine buildings now come tinged with a dusting of racial guilt. Meanwhile, victories in the class war seem thin on the ground. We are adrift.

What is striking about this evolving story of self, and I must point out that this is about the narrative, not the individual, what is most striking is that it does seem to cohere around a strong sense of grievance for slights endured – a mutual connection made through the collective swallowing of bitter pills made palatable by the odd-football win. Of course, many will simply feel this description does not fit and may take offence at any perceived slight on their scouse identity. But this project to manufacture a sense of separation is very real.

In my view, we are being sold a pup and it’s one that needs to take a trip back to the vet. While we gripe against lazy stereotypes in the media, we are, in truth, guilty of playing to them ourselves and too often take on these restrictive ideas as our own. Liverpool, and I say this with genuine love, is in danger of becoming an addict to its own class-A narrative.

Stuck in the past – where’s our sense of agency?

I’m conscious I need to explain how I think this works and why I believe it’s so dangerous to our health of mind and our future prospects. Let’s go back to that Liverpool Echo article and the popular argument. It has the benefit of simplicity. It goes like this… our sense of grievance, which is legitimately founded, is fuelling our independent, republican spirit, our demand for fairness and our rejection of Englishness, and this is entirely understandable and in some ways positive. It is up to the English and the English alone to make good or we’ll carry on our separate way. Should you be so minded you can buy the mug or the t-shirt and proudly proclaim your support for the Scouse Republic.

Now let me explain what I think is really happening. It ain’t pretty. Strap yourself in. I won’t be winning any prizes for popularity.

My argument is that our sense of grievance is fuelling not a positive assertion of independence but a downward spiral into insularity. The modern sense of political scouse identity that we are being encouraged to adopt, is a perversion of the positive and energetic forms that went before. It is forming primarily around negative assumptions – everyone hates us, we never get treated fairly, we have to fight for everything, and the outcomes that we want are largely beyond our control. There is a sense that the game is rigged against us, feeding a loss of faith in government authority both in Westminster but also increasingly at the local government level too. That’s one of the reasons why we’ve been seeing such low electoral turnouts. After all, if you view things that way, what is the point?

“Our sense of grievance is fuelling not a positive assertion of independence but a downward spiral into insularity. The modern sense of political scouse identity that we are being encouraged to adopt, is a perversion of the positive and energetic forms that went before.”

A primary feature of this outlook is pessimism and a loss of faith in the future. Our belief in our own agency to identify and solve the city’s problems and to conceive of big, ambitious solutions is becoming eroded over time. This is why today, in Liverpool of all places, we feel the pull of the past so strongly, expressed as it is in our stubborn defence of heritage (even when it makes no sense) or our determination to keep fighting old battles long after the social forces that made them have ceased to apply. Looking to the past is simply more reassuring because there is already a map to guide us and our obsession with the 1980s is at least in part, down to this nervousness about our future. It is also a politically convenient way of passing the buck.

As we struggle to find solutions to the problems we face and lose hope of better outcomes, our instinct as proud men and women of Liverpool is to throw our ire outwards, to say, ‘Sod you’ to the rest of England, which as the mooted source of our suffering is cast as the villain (the Scots, Welsh and Irish have our sympathies as they are also considered to be under ‘the yolk’). So then we double down on our own sense of uniqueness - we are hated because we are different - which is mostly a palatable rationalisation of our own sense of defeat. Of course, some people just go away, fire up their belly, and take charge of their lives, for example by setting up a business in places like the Baltic. Others just go away. Meanwhile, as a community, we re-commit to our grievances.

Unfortunately, despite the likelihood of a new government and a change in policy direction, there is little prospect of a shining knight riding over the hill to rescue us. We know this, don’t we? Our grievances serve no purpose in a battle we cannot win. All they do is fuel our sense of powerlessness. What we need to do as a city, as a people and as individuals is to reclaim our sense of power and agency and we can only do that by just doing it. Some, like Metro Mayor Steve Rotherham, will argue that this is why he is trying to gain more powers for the Combined Authority so that the region can exercise more control over decisions and that is right. But unless our leaders can find a way to turn their backs on the dominant pessimism of these times, they will dream only little dreams.

What ‘Scouse, not English’ and the backward-looking forever-focus on the 1980s offer us is a shrunken vision of our place in the world. A tiny Scouse Republic of Retreat - a new Pimlico. Sure, it doesn’t require a passport for entry and exit, but just like in that famous Ealing Comedy, it brings with it a wariness of the outside and a closing of doors at the exact time we need to be opening them. We should have no truck for this limited and carefully edited version of ourselves, this ‘Petty Scouser’ mentality. Instead, let’s stand tall, be open to the world and claim our confident place amongst it.

So, back to Thatcher and Toxteth

A little section here about our 1980s obsession and who stands to benefit. Let’s be clear. When in 2022 people re-raise folk devils from 40+ years ago as if they are still relevant, they are doing it for a reason. In Liverpool, it gives activists and elected representatives an alibi, allowing them to point the finger of blame outwards for the city’s sorrows, instead of looking within. It’s a way of avoiding scrutiny and of taking responsibility for inventing new stories and new sources of power and success. It’s time we all got wise to it. We deserve better.

More concerning though is what an over-zealous focus on the past communicates to the world outside and to the people we’d like to partner with. Forever talking about the 1980s pins us as irrelevant, backward-looking, and worst of all, passive in the face of the present. By using long-gone events to explain the outcomes of today, we risk turning ourselves into victims of history, still driven by events we cannot change. Time to let go.

What’s in a name?

At Liverpolitan, we’ve often been chided for adopting such a name. Why didn’t we use Liverpudlian? Nobody calls themselves a Liverpolitan. But exercising our agency means waving goodbye to insularity and engaging fully with the world around us. It is our signal that this country and in fact the whole planet is full of Liverpolitans making their way beyond the narrow confines of the city limits. What is remarkable about many of these people, is that though their lives have taken them elsewhere, they retain their passion for their ultimate home. They are a resource, they are legion and they are on our side. We should use them.

Last words to Joanne…

So what did the Mayor say that was so interesting? If we are being honest, it is the Left in the city that has been more prone to mining the past. You can argue it’s been an election-winning strategy, but that doesn’t mean it’s the right thing to do. So when the Labour Mayor of Liverpool tells us it’s time to face forward, I think we should listen. Here’s what she had to say.

“Every city has its challenges, and Liverpool is no different. But outdated scouse stereotypes and harking back to the 1980s does not define our city today. It is blatantly obvious that the city has undergone massive transformation and is continuously evolving. We have a dynamic culture and arts scene and major regeneration projects, whether it’s the growing health and life sciences sector, the film studios on Edge Lane, or Bramley Moore Dock. It is damaging when publications rely on the same old tired cliches and narratives about Liverpool, as it just perpetuates old myths that simply are not true. Liverpool is looking forward with optimism – maybe it’s time others do too.” Joanne Anderson, Mayor of Liverpool.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach

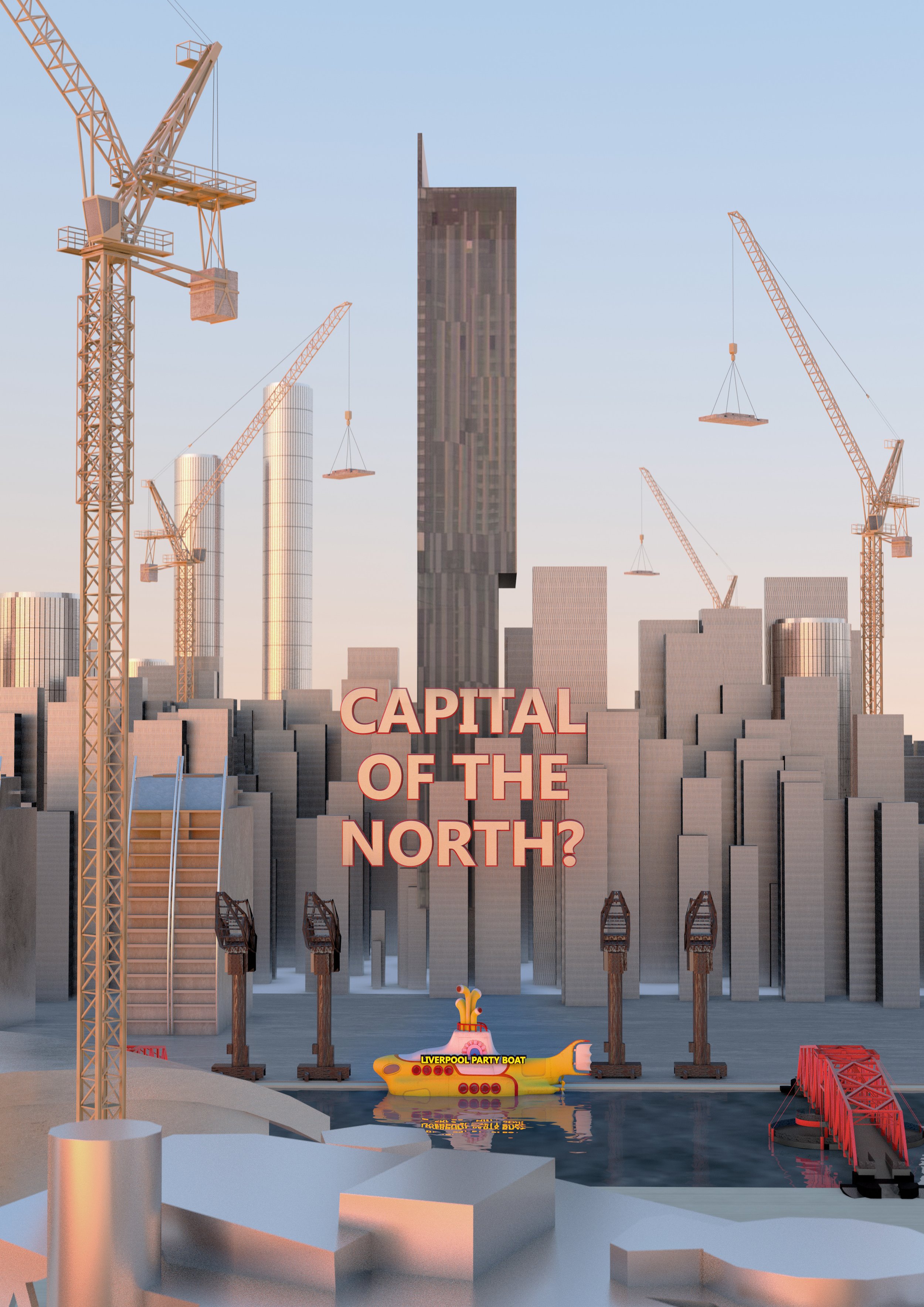

*Main picture by Alex McCarthy on Unsplash

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Devolution Derailed: When trust turns to dust

The breaking of the mayoral promise for a referendum on the way Liverpool is governed will have lasting effects on voter engagement. Trust has not just been lost, it’s been shat on and flushed into the river. But it’s not too late to change tack. Do councillors have the guts and the smarts to change their minds, put self-interest to one side, and give the people what they desperately need?

Matt O’Donoghue

Elected Mayors. Cabinet or Committee. Devolution. Who wants any of it and who really cares? Well, we all do and those who don’t really should. The more say we have over the way we’re governed, and the way we raise and spend our taxes, the better. But what good is having an opinion about how your city or region is run, if your voice is only listened to but never heard?

A proper referendum – not a ‘consultation’ on just the Mayoral Model – but one that gives the citizens a real choice in how they are governed is what the political nihilists of Liverpool need. Encourage them to step away from the edge, to stop blaming the Tories and their Commissioners, or Joe Anderson and his cronies, and let the people take control of their future.

The current debate over an elected Mayor for Liverpool, and who should have the final say, has more than the malodorous whiff of déjà vu. We could have hot-wired the flux capacitor and jumped into the Doc’s DeLorean to step back to the future of the Cunard’s Council Chambers circa 2012 and barely noticed the difference. Many of the same faces are there. Just as Joe’s army of acolytes did, back when he was Labour Leader of the ruling party, so Joanne Anderson and today’s elected members appear to have snatched the option to choose how their city will be governed from the fingers of its citizens. The best you can say is that it took the current Mayor until January 26th - that’s ten months - to break her manifesto pledge and her media promises for a referendum.

Accusations of ‘betrayal’ and ‘u-turn’ by Mayor Joanne Anderson on this issue, however true they may be, are as pointless as the consultation that her passed amendment is likely to deliver. The binary ‘yes’ or ‘no’ choice that the citizens are likely to get is an exercise that’s estimated to cost £120,000 and will not be legally binding. It serves to appease and to distract. At its core this is about far more than whether to elect a City Mayor. This is about popular engagement and allowing the people to finally have their say over how their city is run; Mayor with a Cabinet, Cabinet and Leader, or Leader and Committee. And it obviously scares them to give the people a choice because our councillors appear to be doing everything they can to make sure this doesn’t happen. Again.

Amid smokescreen-claims that the estimated costs of any full referendum would be £450,000, the Mayor’s post-election pledge that she could be trusted to deliver a legally binding vote have been turned to ashes. As one council insider put it;

“She really should have looked under the bonnet before she promised to put the car back on the road.”

But the importance of a push towards a re-engagement with politics and how the Liverpool City Region’s capital is governed cannot be underestimated. The people of Liverpool deserve this much after being taken for granted, and for fools for so many years. Trust has not just been lost, it’s been shat on and flushed into the river. Never have the people of Liverpool felt more disillusioned with - and more distanced from - those they elect.

When Manchester voters were handed their referendum they chose to reject Mayoral and Cabinet governance and to stick with the Committee system, led until recently by Labour’s Sir Richard Leese. In this city, Labour holds 94 of the 96 seats. Of course, we still ended up with the ‘King of The North’, Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham imposed upon us from above. But in terms of the city authority, we never missed what we never had, a spare Mayor to push the city’s interests. But at least we had our say through a referendum and the people were engaged with the political process. They said ‘no’ in a way that had to heard.

Trust has not just been lost, it’s been shat on and flushed into the river.

When it came to Greater Manchester’s Mayor, like Liverpool, the toy came without instructions. Our two great cities and our regions were political petri dishes. This was Call-Me-Dave Cameron’s experiment in devolved democracy and we just had to get on with things as best we could. But both experiments have had disastrous consequences because transparency and accountability have become an ‘inconvenience’ in the dash towards devolution. I spent the last decade as a journalist exposing the effects of these slippery standards in integrity and investigating the statutory failures of governance and oversight that got us here, in Liverpool and Greater Manchester.

In Greater Manchester, the Mayor was handed the Policing and Crime Commissioner’s duties. Where once we had a monthly Police Committee made up from elected members with statutory powers of oversight and audit responsibilities over the country’s second largest constabulary, now we have Baroness Beverley Hughes who was appointed by Andy Burnham. Oversight has slipped and with it transparency, leaving the Fourth Estate (the media) and its journalists to hold the police to account for their failings and to expose the devastating effects on individuals.

Perhaps Greater Manchester Police was too complicated or contentious for the new office to deal with? Whatever the reasons, we now have a new computer control system that’s possibly £80 million over budget - we can’t find out for sure because the Mayor’s office has refused to answer the Freedom of Information requests - and it still doesn’t work more than two years after it was switched on. It’s likely that the Integrated Police Operational System - or iOPS - will soon be binned. Tens of thousands of victims have not received justice because their crimes have been ‘lost’ and tens of millions that should have been spent on front line policing has been blown on consultants and a computer that says ‘no’. What’s certain is that the Police Committee, whose meetings I used to attend, would have publicly asked the questions of the Chief Constable that could have halted this slow-motion car-crash and this disaster may have been averted before the damage was done. Instead, we had complicit cronies of the Chief who covered up his failings. Those who should have held him to account either didn’t see, or chose to look the other way. Sounds familiar?!

One telling difference between our two regions is the excellent job that The Manchester Evening News and the fearless Jennifer Williams did to investigate and hold authorities to account. If only The Liverpool Echo had been so diligent, rather than acting as if they were a branch of Joe Anderson’s official communications team for so many years, perhaps then the rocks would have been turned over much earlier.

Despite continual warnings from whistleblowers and the stories from those brave journalists who fought to give voice to their claims of cronyism and coverup, it took two years for the ‘King’ to kick his Chief Constable to the kerb. This only happened after an investigation by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabularies which exposed all the truths that we had broadcast and published. Finally, GMP was placed into ‘enhanced special measures’. This was the first time a police force had been found out to be operating so poorly. Andy Burnham’s nose was rubbed in it by authorities higher than himself, before he admitted that he could smell the stench and cleared the air. The best you can say is that Andy Burnham’s wilful ignorance was born of his desire to be liked and to avoid conflict - little comfort for the countless victims of rape or assault who never saw an officer because his computer kept crashing, meaning the crime was never investigated. Even so, ‘The King’ was re-elected in 2021 with 67% of the vote.

Transparency and accountability have become an ‘inconvenience’ in the dash towards devolution.

Look to Liverpool and we see a familiar pattern; an overwhelming political majority for Labour and an elected Mayor with the powers that were once held by Committee members, now in the hands of one person. The similar failings in oversight, transparency and accountability that allowed Greater Manchester Police to spiral out of control, and the same lack of integrity in those elected to serve our best interests, have brought Liverpool to the brink of financial ruin and political shame. This complete failure of the devolution experiment and the democratic governance that was supposed to hold the Mayor to account has delivered - ‘The Commissioners’, plus a former Mayor and his officers who are ‘released under investigation’, and a financial black hole the auditors say gets bigger by the day. But please don’t let them use this to fool you into thinking ‘Mayor-Bad’, ‘Leader-Good’.

The shift to elected Mayor delivered the adoption of the “Cabinet Model” of Governance creating new Committees for Regeneration, Communities, Education and more besides. These Cabinets are chaired by Leads who sit with their members, to consider and vote on the issues before them. As their reward, all Lead Members receive a top-up, or ‘Special Responsibility Allowance’ of around £13,000 on top of the £10,500 they receive as a councillor. And they are appointed by the Mayor.

The power of patronage means it pays well to stay close to “Big Joe” and “Joanne”. Under this style of constitution the idea of “delegated responsibility”, that always existed, is focused on the Mayor and their Cabinet Leads. They can choose to vest the authority they have to approve matters under consideration into the hands of Departmental Directors. In theory, this should make the resolution of difficult matters much quicker. For example, urgent business deals can be dealt with before they collapse. In practice, it has meant schemes like the Tarmacademy were railroaded through council without the proper scrutiny.

By a deft sleight of hand and before the end of 2015, the only two committees that were asking difficult questions about policies and performance - The Mayoral Select Committee, and The Overview and Scrutiny Committee, were ‘disappeared’. Mayor Joe Anderson left oversight and transparency in his wake with barely a look over his shoulder. Even so, in 2016 the voters of Liverpool still returned Mayor Joe for a second term on a reduced majority of 52%. But inside the Labour Party mutiny loomed on the horizon.

On the eve of the 2019 local elections, Joe Anderson’s own former Deputy Mayor, Anne O’Byrne, wrote her mutinous clarion call for rebellion and change. Under the flag, “Why Liverpool needs to return to a Leader and Cabinet Model”, she posted her assault on a system in which she had once been key.

“We’ve done a lot of things well (since we swept to power in 2010), however over the past few years the whole of the city has seen the problems of the Mayoral model being too centralised, adopting a Presidential style of decision making.”

Councillor O’Byrne continued her Trumpian-takedown of the way her boss did business.

“The current mayoral model insulates the Mayor from criticism. A Mayor does not hold surgeries, report regularly to the Labour Party branch and does not represent a ward that would ground them in the issues people raise on a daily basis.”

The mayoral structure, according to his one-time deputy, insulated him in an ivory tower and away from all the problems and concerns of his councillors and the electorate who voted for him.

In doing away with the position of Leader of the Council and in concentrating all power in the hands of an elected Mayor, Joe Anderson may have hoped the new system would be more dynamic, with faster decision making. He was to be the boss and his close-knit ‘gang’ would get the job done. But while listening to and communicating with councillors and communities may take a bit more time, Councillor O’Byrne wryly remarked, “It means you make better decisions for everybody and not just a selected few.”

As the electorate of Liverpool prepared to cast their 2019 votes, the Deputy Leader of the Labour Party saved her most devastating lines for last;

One telling difference between our regions is the excellent job that The Manchester Evening News did to hold authorities to account. If only The Liverpool Echo had been so diligent.

“The Mayoral model lends itself to meetings with developers, investors, Whitehall mandarins and Tory ministers in order to have a top down approach to developing the city. The people of the city have no role other than voting for the Mayor once every four years. The rest of the time they are seen as obstacles to development, not integral to the process of inclusive growth.”

Councillor O’Byrne’s depth charge was still making waves as the Labour Councillor for Knotty Ash, Harry Doyle, looked forward to working with and speaking up for his residents. In a ward once famous as the home of the comedian Ken Dodd, Councillor Doyle was more likely to be concerned with the community legacy of Liverpool Football Club’s former training ground, Melwood, than looking for a fight with the man now known as ‘Big Joe’.

Yet less than a week after the count, a leaked email chain exposed Councillor Doyle’s true feelings about his life inside Liverpool Council. “During my induction day last year, a council officer advised new councillors that 95% of decisions are made by the Mayor,” he wrote. “This is a figure that baffled me as it made me wonder what role we backbenchers have to play in policy formation.” In his leaked emails, Doyle echoes the sentiments of the former Deputy Mayor, from her night-of-the-election tweet. He wrote “It centres all of our decision-making around one person, and some decisions are not made clear to us until they’re made clear to the public via the press.”

Is it any wonder that the people who’ve watched their city carved up and sold off on the cheap have begun to abandon hope for change and trust in those they elected to deliver a better life? ‘They’re in it for themselves’ or ‘they can’t do a thing’ becomes ‘my vote makes no difference’ and soon gives way to ‘what do I care?’. And once that wall is built between the people and their politicians and it becomes unscalable, who will rise up to knock it down? The Infidels? Militant? Extreme disaffection can feed extreme politics. Councillors, be careful what you vote for.

As a proud woolly-backed Lancastrian and adopted Mancunian, married into Old Swan heritage, I believe the affairs of both cities bookending the western stretch of the M62 are important to our mutual understanding and growth. Only those who’ve breathed life in the Liverpool City Region or in Greater Manchester can truly begin to know what’s going on here, and what needs to be done in the best interests of the people whose lives and jobs reside here. Well, that assumes the people in charge actually have the best interests of their electorate held closest to their hearts… rather than their own careers, or those of the businesses and individuals of influence who drip poison in their ears.

From Corbett and Conception, to Kemp and Crone; the elected representatives of Liverpool still have the chance to unite. Mayor Joanne Anderson, must jump down from that conveniently climbed fence and make a difference for those citizens who feel their trust has been misplaced. It is they who must shoulder much of the blame for what has passed and the political embarrassment that Liverpool became. Their wards elected them to serve, and instead they passed motions that concentrated powers and blinkered oversight. They cancelled the Committees that created accountability, and set up Cabinets led by cronies. And when their constituents came with complaints about the scam developments blighting their neighbourhoods, or the Cabinets rubber stamped back-door-disposals of the city’s Crown Jewels, they found they were powerless to stop things, or too late to change them. Now is their chance to consult, to listen to those voices calling for respect.

The practice and custom of a one-size-fits-all set of policies that are dictated from a Westminster and London-centric government just doesn’t work for any of us any more. Our regions are individual and different and only a federation working together and towards the common national good can be the right way to go. This country’s regions have their own characteristics, their own needs and their own strengths. You can’t properly understand a place unless you’ve lived, loved and listened to its citizens. And heard what they have to say. To deny a ‘proper’ referendum – in favour of some ‘Mayoral Choice’ - is so much more than a sacrifice of the alternative. In a city where the councillors barely have a grip on costs, let alone appreciate values, what price to encourage engagement with ‘democracy’ and to deliver on a promise?

Matt O’Donoghue is an investigative reporter who has worked for the BBC and ITV including Granada Reports and Newsnight. He is a previous winner of the O2 Broadcast Journalist of the Year, ITV Correspondent of the Year and has won numerous awards from the Royal Television Society.

Share this article

The Beatles: Inspiration or dead weight?

When does city pride in the Fab Four turn into a hindrance to future achievement? Jon Egan argues that the city of Liverpool is in danger of becoming a Beatles theme park, and its world conquering band a crutch to exorcise the painful intimations of our diminished relevance and prestige. In looking to the past, have we forgotten what made John, Paul, George and Ringo so special - their fearless embrace of the avant-garde, the contemporary and the new?

Jon Egan

There was something profoundly true and desperately sad in University of Liverpool lecturer, Dr David Jeffery's acerbic observation that "Liverpool is a Beatles' shrine with a city attached."

It is the dispiriting obverse to music journalist, Paul Morley's rhapsodic description of Liverpool as "a provincial city plus hinterland with associated metaphysical space as defined by dramatic moments in history, emotional occasions and general restlessness."

Jeffery's comments on Twitter appear to have been inspired or provoked by the recent announcement that Liverpool would be using a £2 million grant from Government to advance the business case for yet another "world-class" and "cutting-edge" Beatles' attraction on our hallowed waterfront. Presumably, it will be sandwiched somewhere between the Beatles statue and The Beatles Experience and conveniently close to The Museum of Liverpool and The British Music Experience with their not inconsiderable collections of Beatles artifacts and memorabilia. The exact nature of this new cultural icon remains a little unclear, however, amidst wildly differing descriptions offered by our City and Metro Mayors.

What is deeply depressing about this announcement is that it suggests that Liverpool is incapable of imagining any kind of cultural proposition that is not predicated on the seemingly inexhaustible allure of the four boys who shook the world.

There is of course a readily available and seemingly plausible justification for the never-ending Beatles' fetish, and that is the claim that they are the anchor for our hugely important tourism economy. Notwithstanding the implication that David Jeffery is right to suspect that the city is consciously morphing into a Fab Four theme park, I suspect that this is not exactly the whole truth. For Liverpool, The Beatles are a crutch, a cherished emblem of identity and importance used to exorcise painful intimations of diminished relevance and prestige.

In the novel, Immortality, Czech writer Milan Kundera tells the story of the man who fell over in the street, who on his way home stumbles on an uneven pavement, falls to the ground and arises dazed, grazed and dishevelled, but after a few moments composes himself, and gets on with his life. But unbeknown to the man, a world famous photographer happens to witness the scene and quickly snaps an image of the bewildered and bloodied pedestrian. He subsequently decides to make this picture the cover image for his new book and the poster for his international exhibition. For the man, a momentary misfortune freeze-framed, replicated and disseminated across the world, becomes the image that will forever define who he is.

The more we conflate the Beatles brand with the city's identity, the less space we have to imagine anything original, contemporary or remarkable.

In a sense, Liverpool is the City that fell over on the street, our external image is in significant part, defined by a succession of misfortunes, afflictions and tragedies that befell the city over two decades at the end of the last century. These events forged images, preconceptions and stereotypes that still blight us today and have never been successfully exorcised or replaced.

The Beatles hark back to a time before this blight, when Liverpool was in Alan Ginsberg's celebrated phrase, "the centre of consciousness of the human universe." They are, I believe, a therapeutic distraction from the task of making a different story or discovering a new identity.

Culturally, our Beatles fixation is unhealthy, debilitating and regressive. In fact, I fear we are reaching a point where The Beatles will become the single biggest impediment to any form of civic progression, or any serious project to make Liverpool important, interesting or relevant in today's world. If we are going to have a civic conversation about what kind of "world class" Beatles attraction should be erected at The Pier Head, my immediate impulse would be to recommend a mausoleum.

But perhaps a more imaginative and original idea was the one offered by the late Tony Wilson. That supreme Mancophile, Factory Records producer, Granada TV reporter and founder of the Hacienda nightclub was never held in particularly high regard in this city, especially following some tongue in cheek words of encouragement he gave to Club Brugge on the eve of their European Cup semi-final with Liverpool in 1977. Scousers may resemble elephants with respect to their prodigious powers of memory, but our skins can sometimes be just a tiny bit thinner. Tragically, Wilson's Mancunian persona and his tendency to lapse into casual profanity whilst presenting his project to civic decision-makers proved the undoing of his brilliant and visionary proposition for POP - the International Museum of Popular Culture. Pitched as the big idea for the European Capital of Culture, and the solution that would provide content for Will Alsop's audacious but otherwise functionless Fourth Grace, POP was a talisman for instant reinvention - a Beatles-inspired attraction without any reference to The Beatles. Alas it never happened.

Wilson had first dreamt of POP as an adornment for his own native city and a fitting celebration of its notable contribution to the history of modern popular music, but he soon realised that it was the right idea for the wrong place. He would often express irritation that when travelling in the US he would frequently have to explain where Manchester was by reference to its proximity to Liverpool - a place that people had actually heard of. And there was also the grudging recognition that at a time when Liverpool was "the centre of the human universe" globalising popular culture - Manchester could only offer us Freddy and The Dreamers. Even the outrageous charisma of Manchester United football god, George Best was derivative as he was often dubbed the 5th Beatle.

POP would not simply have been about popular music, it would encompass every facet of popular culture, every expression of contemporary creativity in film, TV, advertising, games, cars, sport, fashion, digital technology and consumer culture. And it was proposed for Liverpool because this was the place that spawned a phenomenon that reached the four corners of the Earth. It was a moment when the world discovered a common currency and a cultural vernacular intelligible to every ear.

POPs content would be dynamic and ever-changing, a continuous exposition of the new, curated by global creatives, designers and technologists. It would be Liverpool recovering its world city perspective and its capacity to invent and innovate - the pool of life, the birth canal for the extraordinary and the unprecedented. Its ingenious paradox was its implicit assertion that The Beatles did not make Liverpool, but Liverpool made The Beatles.

They monopolise our self-image occluding facets of identity and history now only half-glimpsed in the penumbra of a shadowy scouse dreamtime.

All of which is a million miles from Steve Rotheram's "world-class immersive experience" which he promises us will be more spectacular than a glass cabinet containing John Lennon's underpants. We can hardly wait.

If all we can possibly imagine are The Beatles etherealised into holograms - almost literally spectres from beyond the grave - then David Jeffery is right and Liverpool's once rich and cosmopolitan culture has collapsed into a black hole of redundant clichés. The more we inflate our Beatles offer and conflate their brand with the city's very identity, the less space we have in which to imagine anything original, contemporary or remarkable. Along with football (which at least tells new stories) they have come to monopolise both our external brand and our officially curated self-image, occluding facets of our identity and history that are now forgotten and suppressed, only half-glimpsed in the penumbra of a shadowy scouse dreamtime.

The Beatles have come not only to represent our brand, but have also helped to define our personality, attitude and accent - cheeky, chippy, sassy and defiant. As emblems of the 60s social revolution, they helped to forge and reify the idea of Liverpool as a working class city - or more accurately an exclusively working class city. As rock journalist Paul duNoyer, notes in his book, Wondrous Place, this is both a false and profoundly disabling imposition. Not only, as Tony Wilson asserted, are we the city that globalised popular culture, but we are a city that has contributed massively to every facet of culture, ideas and invention over the last 200 years.

The world's first enclosed dock and inter-city railway, together with the completion of the Transatlantic telegraph cable, are not only stunning achievements in technological innovation, but bolster the credible claim that globalisation began here.

The extent to which we have been willing to squander or disown the breadth of our cultural heritage was brought home to me in the febrile final stages of the European Capital of Culture bidding competition. Having commissioned pop artist, Sir Peter Blake to create a homage to his iconic Sgt Pepper album cover to remind the world, or at least the judging panel, of Liverpool's cultural and intellectual prowess, the task of deciding who exactly was worthy of inclusion was both fraught and enormously revealing. Apart from a few contemporary, and at the time highly topical creatives including the poet Paul Farley, artist Fiona Banner and film-maker Alex Cox, the principal criterion for inclusion appeared to be the directness or intimacy of connection to The Beatles. A lop-sided bias towards musicians, popular entertainers and Sixties icons meant no room for the likes of painters George Stubbs and Augustus John, poets Nathaniel Hawthorne and Wilfred Owen, novelist Nicholas Monsarrat, playwright, Peter Shaffer or even poet and novelist, Malcolm Lowry the author of the celebrated, Under the Volcano. Incredibly, until Bluecoat Artistic Director, Bryan Biggs' finally succeeded in persuading Wirral Council to erect a blue plaque on New Brighton's sea wall, there was virtually no public recognition that one of the 20th century's greatest and most influential novelists had any association with the Liverpool City Region.

Without questioning or diminishing the impact of the Mersey Sound poets (McGough, Henri and Patten) in the 1960s, their literary status is no way comparable to another unsung and forgotten cultural luminary with a significant Liverpool connection - C.P. Cavafy. Now acknowledged as one of the last century's most important and original poetic voices, Cavafy spent much of his childhood at addresses in Toxteth and Fairfield. Greek and gay, his poetry will forever be associated with the city of Alexandria where his family settled after leaving Liverpool. We do not know to what extent his formative years in the city helped nurture Cavafy's creative animus, but transience, up-rootedness and departure are woven into our narrative. Our sense of self and place in the world as Liverpolitans, owe as much to those who moved on, or merely passed through, as they do to those who stayed or settled here.

We are not, and never have been a monochrome canvass or a one trick city. Our culture is dense, deep and multifarious, formed by a hotchpotch of races, creeds and classes. For those tasked with defining a place and communicating its uniqueness to the world, there is always the temptation to reduce and simplify.

Brands, including place brands, are often conceived like Platonic forms - a distilled essence, fixed and immutable. But cities like Liverpool are neither simple nor static, and are thus frustratingly un-brandable. Described by Wilson as a place with "an innate preference for the abstract and the chaotic," our essence is pre-Socratic - unresolved, unpredictable and disconcerting. We know that port cities like Liverpool, Naples, Barcelona and Marseilles have historically been melting pots for ideas, influences and cultures - places where things never quite settled.

But their edginess is not merely a function of a perturbed diversity, it is also literal. It's connected to Marshall McLuhan's philosophical idea of right hemisphere sensitivity and the expanded perspective of what he terms acoustic space. Ports face outwards, they are perched on the precipice of a vast and formless abyss. It's an omnipresent reminder that there are no limits.

For Paul Morley, Liverpool’s character and identity - its ability to charm, entertain, inspire and infuriate - proceed from an inchoate restlessness and fidgety creativity. It's a place "where something happens, most of the time, leading to something else." But it seems like that creative energy and inventiveness have deserted us - or at least our leaders. What was once an animating pulse has been reduced to a piece of hollow rhetoric - a brand attribute.

It's sad that a UNESCO City of Music should have forsaken polyphony, and that we are continually stuck in a repetitive groove, narrowing our identity and stifling our capacity to be original (again). For this reason the very last thing Liverpool needs is yet another Beatles' attraction, even an immersive one.

So, OK, The Beatles were important, are important. They changed the world, but did they change Liverpool? We're still, I hope, the city capable of creating something else.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

Life after Joe: Ditching the Mayor won’t fix our broken democracy

There’s something nearly all of Liverpool’s political parties agree on - the need to abolish the office of directly elected city mayor. But are their positions based on principle, self-interest or just faulty logic? In 2022, the public should get to decide the question for itself in a referendum, but with such a one-sided campaign in prospect, there’s an acute danger that we’ll sleep walk into this vote without the chance of a properly informed debate.

Jon Egan

When nearly all of Liverpool’s political parties agree on something, you can bet it’s on an issue of mutual self-interest rather than in defence of any cherished principle.

As things stand, Liverpool’s voters will be invited, most likely in 2022, to decide whether to keep or dispense with the office of directly elected city mayor. It promises to be a rather one-sided campaign with the city’s three largest political groups (Labour, Liberal Democrats and Greens) all arguing for abolishing the post and returning to what they collectively describe as the “more accountable” Leader with Cabinet structure.

Even our recently elected incumbent, Mayor Joanne Anderson, is pledging to vote for the abolition of her own job, which begs the question, why she was so anxious to run for office in the first place? But of course, she was not alone. In the 2021 mayoral election, only two candidates - the Independent, Stephen Yip, and the Liberal Party's Steve Radford - were actually standing on a pro-mayor ticket. Indeed, following the unprecedented intervention by Labour's ruling National Executive to disqualify all three of the senior councillors on the original selection shortlist, both the Labour and Liberal Democrat council groups attempted to cancel the election by abolishing the role without recourse to a public referendum, until they were stopped in their tracks by polite reminders from their own legal officers that such a move would be unlawful.

There is an acute danger that we will sleep walk into this referendum without either a campaign or a properly informed debate. Voters will be asked to reflect on the need to learn lessons from euphemistically labelled "recent events" and fed the seemingly plausible line that one mayor is better than two. After all, why do we need a city mayor now that we have a metro mayor?

Of course, there is a shadow hanging over this whole discussion – one powerful argument for the case against elected mayors – which comes in the shape of the now under investigation and widely discredited former mayor, Joe Anderson. For some, he has become a walking metaphor and deal-sealing symbol of the dangers of too much power in the hands of one larger than life individual. But this is too important a decision for knee-jerk reactions. Our democracy demands that the subject be properly examined and debated. It’s too easy for us to be seduced by over-simplified and questionable arguments. We should think hard before dispensing with a model, that I would contend, has never been properly embraced or tried by our local politicians.

There is an acute danger that we will sleep walk into this referendum without either a campaign or a properly informed debate.

Before we head off to the ballot box (presuming we get the chance), there are some key questions we have to consider. Are mayors generally a good thing? Can they achieve results that old-style council leaders can't? Is there something specifically about Liverpool and the state of our local governance, our politics and our economic and social predicament that makes having a city mayor here particularly desirable or dangerous? And how are we to make sense of our experience of the mayoral model to date? Are the critics right that the concentration of power has been unhealthy or even corrupting?

But first… a little context. Let’s delve back into the city’s recent history to find out how we ended up in this mess. City mayors were an early prescription for what is now fashionably described as ‘levelling-up.’ The problem of a seriously unbalanced economy and underperforming urban centres was a matter of serious priority for the incoming New Labour government in 1997. The publication of Towards an Urban Renaissance - the report of Lord Rogers' Urban Task Force was a seminal moment in re-prioritising the importance of cities as vital engines for growth, innovation and national prosperity.

We’ve been here before - Liverpool’s democratic deficit

Harnessing that growth, it was implied, would require a new kind of energised civic governance similar in form and style to the dynamic leadership that had successfully regenerated European and North American cities such as Barcelona and Boston. In contrast, the fragmented committee structure of local government, then dominant in the UK, was seen as a recipe for old-school inefficiency and a failure of imagination. A new Local Government Bill (2000) set out the options to reset civic democracy. There was no coercion; just three choices: Leader and Cabinet (close enough to stay as you are), and two flavours of the big bang option for directly-elected City Mayors. Towns and cities were free to decide for themselves and unsurprisingly, councils overwhelmingly chose the least change option with only a handful willing to embrace the more radical mayoral restructure.

In Liverpool, however, the idea of a directly elected mayor aroused immediate interest, though admittedly not amongst our politicians. Instead, the city's three universities, its two largest media organisations (BBC Radio Merseyside and the Liverpool Echo) and a collection of faith leaders convened the ground-breaking Liverpool Democracy Commission in 1999. Under the chairmanship of Littlewood's supremo, James Ross, the independent commission brought together politicians, academics, and community and business leaders such as Lord David Alton, Professor of Urban Affairs, Michael Parkinson (now of the Heseltine Institute), radio presenter Roger Phillips, and Claire Dove, a key player in the local social enterprise movement. They took evidence from national and local experts and were shadowed by a Citizen's Jury to widen representation. In turn, the city council made a commitment to consider its recommendations and, if a mayoral model was advocated, to hold a public referendum.

From its inception it was clear that the commission was not simply evaluating the general merits of the available models, but was considering their applicability to Liverpool’s very particular local circumstances. Those circumstances included a wretched turnout of just 6.3% when a tired and divided Labour administration lost its majority in the crucial Melrose ward council by-election in 1997, the lowest ever poll in British electoral history. A Peer Review of the troubled council at the time by the Independent and Improvement Agency had painted a picture of lethargy, cronyism, an insular town hall culture, and wretchedly poor service delivery. Liverpool was acutely aware that its civic governance required a radical reboot.

Leaders run councils, Mayors run cities

The more general case for a directly elected mayor centred on its ability to reinvigorate local democracy, transferring the focus of civic leadership from the inner minutiae and manoeuvrings of the town hall to the wider city – its communities, businesses and institutions. As local government academic Professor Gerry Stoker put it when giving evidence to the Democracy Commission, “Leaders run councils, mayors govern cities.”

Stoker was by no means alone in advocating this radical change. Evidence from witnesses, community meetings, public surveys and the Citizen’s Jury converged on the same transformational proposition. Mayors could be convenors, able to galvanise civic energy by bringing multiple parties together in partnership. They would change the destiny of places in ways that our stilted and bureaucratic town halls could never hope to emulate.

Against this backdrop, the idea of giving every citizen the opportunity to vote for the city's leader seemed refreshingly progressive. It also offered a tantalising possibility - a radical break with party politics. Theoretically, the elected mayor system provides a level playing field for independent candidates. No longer would political parties with the networks and infrastructure required to support candidates in all of the city's wards be able to monopolise the system. Politics could be open, unpredictable and much more interesting and the talent pool from which to select a city leader was immediately expanded. Clever and experienced people from business and civil society would step forward to offer themselves for election.

But above all, it was the radical simplicity of the democratic contract that commended the mayoral model. No longer would local democracy be transacted behind closed doors, shrouded by arcane traditions and enacted through the inscrutable election-by-thirds voting system that somehow allowed political parties to lose elections but miraculously stay in power. With a directly-elected mayor, there would be visible leadership, clear and simple accountability and a transparent means of returning them or removing them from office.

By blaming the mayoral model for the shameful abuses and failures identified by Caller, our councillors are indulging in a transparently hollow attempt at self-exoneration.

It was for that reason that elected mayors were pitched as the antidote to voter disaffection, not just in Liverpool but across the whole country. Turnouts for local elections were in decline everywhere resulting in a widely acknowledged crisis of legitimacy.

Legitimate or not, one year before the Democracy Commission was founded, Liverpool’s voters had their say, overcoming their most ingrained cultural instincts to throw out what they knew was rotten. Liverpool's Labour administration was swept from power by an almost entirely unpredicted Liberal Democrat landslide.

So it would be a Liberal Democrat administration that would decide whether to adopt the mayoral model and respond to the unequivocal recommendation of The Democracy Commission. But they fluffed their lines, embracing instead the less radical option offered by the New Labour government – a Leader with Cabinet. Not for the first time, our political leaders knew best. Rather than allowing voters to choose their preferred model via the referendum they had promised, the council opted for the one that suited their own ends best.

Paradoxically, Liberal Democrat Council Leader, Mike Storey’s style and swagger were almost mayoral. He set up the UKs first Urban Regeneration Company (Liverpool Vision) and boldly calibrated a vision of the city as a European Capital of Culture. These were heady days, and many will now look back nostalgically on Storey’s early tenure as a time of almost limitless promise. So what went wrong?

Storey was instinctively attracted to the idea of city mayors and thought he could be one without having to navigate this dangerously Blairite and centralising heresy through his notoriously individualistic and anarchic Liberal Democrat Party. But Storey was constrained both by the instincts, prejudices and personal ambitions of his own political group, but perhaps more importantly, by the absence of an independent democratic mandate. His leadership rested on the confidence and acquiescence of his unruly Lib Dem caucus, but also on the compliance and co-operation of his highly ambitious Chief Executive, Sir David Henshaw - a challenging job at the best of times. From the outset, some had feared being left out in the cold by this high profile vote winner and knives were sharpened. Without a personal mandate from the public, it was difficult for Storey to face them down. The image of a beleaguered leader imprisoned and frustrated by an obstructive town hall bureaucracy was painfully and comically exposed in the infamous "Evil Cabal" blog. This was local government reduced to camp farce.

The fact is, Storey’s leadership and authority waned precisely because he was not a mayor. He lacked the clear constitutional and democratic authority to deliver on his mandate and to prevail over vested interests and personal agendas. At the end of the day, he was too much a part of a system that was still instinctively protective and self-serving.

Where power really lies

This may appear to be a subtle and rather academic distinction, but the source of a council leader's authority is always municipal rather than civic. The democratic process is indirect and opaque, and real power rests with councillors, not voters. It is councillors who choose the leader, and it is councillors who can topple them, even outside of the local election cycle. Ultimately, council leaders know who they are answerable to and are inclined to act accordingly.

Eventually Storey was forced to resign and after his nemesis, Henshaw, had departed, the Liberal Democrat regime lapsed into a familiar pattern of failure and chaos, mimicking its Labour predecessor. Before long it was being tagged as the country’s worst performing council, and was dumped out of office by an unlikely Labour revival. The compromise option of The Leader with Cabinet model had not ushered in the promised golden age of civic renewal, but only dismal continuity and an all too familiar story of town hall intrigue and ineptitude.

For the incoming Labour administration, the mayoral option was perceived as a threat, not an opportunity. Liam Fogarty’s Mayor for Liverpool campaign was gathering steam, and its petition heading towards the tipping point where a public referendum would have to be negotiated. For Fogarty, the slow implosion of the previous Liberal Democrat administration was evidence that the problems were systemic. He believed that only a new model which transferred more power to voters could fix Liverpool's dysfunctional municipal culture, and that the authority of leaders must rest on a direct personal mandate from the public.

Fearful that a referendum campaign would be a platform for a powerful independent, and in an act of supreme cynicism, Joe Anderson invoked a hitherto unsuspected provision of the Local Government Act to transform himself into an “unelected” elected mayor. It’s worth remembering that Labour’s adoption of the model was motivated solely by a neurotic phobia of a Phil Redmond (creator of popular TV soap-opera, Brookside) candidacy, rather than any intrinsic attraction to this radical new way of running a city. In truth, Liverpool Labour never believed in elected mayors and the shambles and shame of Anderson’s last days provided it with a perfect opportunity to dispatch the idea once and for all.

Boss politicians and the school of hard knocks

Anderson's sleight of hand once again deprived Liverpool voters of the opportunity of a referendum where the mayoral model could have been properly debated and explored. The fact that it was adopted without enthusiasm or any thorough consideration of its merits, is perhaps the explanation for what subsequently transpired. Anderson did not rule as a convening mayor - as envisaged by Stoker and advocated by the Democracy Commission - dispersing power, building coalitions, and using soft levers to nurture civic cohesion. He was an old-style Labour “City Boss” – in the style and tradition of Derek Hatton, Jack Braddock, Bill Sefton and a host of less memorable and notorious predecessors. Anderson’s approach was that of a fixer and deal-maker - a pugnacious “school of hard knocks” political operator who once threatened to punch a Tory Minister on the nose for claiming that austerity was over.

If Mike Storey was a council leader masquerading as a mayor, Joe Anderson was a mayor acting out the role of a traditional boss politician. What Storey lacked in terms of authority and mandate, Anderson lacked in terms of subtlety, collegiality and an overarching civic perspective.

During a mayoral hustings event in 2012 at the Neptune Theatre, an audience member posed the challenge, what is Liverpool for? A tricky question and one that demanded a perspective beyond the familiar horizons of the council budget and Tory assaults on its finances. Anderson seemed utterly dumbfounded. Only Liam Fogarty was able to grasp that existential questions like these cannot even be perceived, let alone resolved, from the myopic vantage point of a town hall bunker. Our politicians were simply incapable of rising to the challenge of a political role that required a radically different set of skills and a civic, rather than a municipal, mindset.

Which brings us to today. In effect, we have had a mayoral model, but we have never had a mayor in the way it was envisaged… as a radical antidote to a broken town hall culture.

It is the supreme irony that the case against elected mayors is now being framed on the record and reputation of Joe Anderson - the very embodiment of old-style Liverpool municipalism with its narrow and insular perspective. The argument that Anderson proves the perils of placing too much power in one person’s hands is a dangerous and misleading sleight of hand; a fallacy designed to obscure both historic truth and the complex considerations that should be informing this hugely important debate about how our city is governed.

The fallacy was set out quite pointedly in the 2021 Max Caller report, with its forensic exposure of Liverpool Council’s systemic municipal failure. In describing the governance structure of the city council, Caller observed:

“although the mayor is an authority’s principal public spokesperson and provides the overall political direction for a council, an elected mayor has no additional local authority powers over and above those found in the leader and cabinet model, or the committee system.”

Mayors are a dangerous idea. Independent candidate Stephen Yip threatened to end party political hegemony in Liverpool with only the meagrest resources. This is an eventuality that establishment politicians must join forces to thwart once and for all.

In effect, the "Leader with Cabinet" model now favoured by our local politicians, places exactly the same amount of power in precisely the same number of hands as the “discredited” mayoral model. In no way is it inherently more accountable or transparent. We are being sold a false prospectus, and one we know from our own recent history is no panacea. This is the classic ruse of the second-hand car salesman, and we need to look under the bonnet before it's too late.

By blaming the mayoral model for the shameful abuses and failures identified by Caller, our councillors are indulging in a transparently hollow attempt at self-exoneration. The “few rotten apples” alibi became the recurrent mantra to explain away the systemic dysfunctionalism exposed by the report. It was all down to the Mayor and a system that allowed a few powerful individuals to operate without adequate transparency or scrutiny. Or so the story goes. The solution is simple, get rid of the Mayor and all will be well.

But there was nothing extraordinary or atypical in Anderson's style, nor anything that was especially mayoral about the municipal culture or the way power was exercised. Caller's report is depressingly redolent of the Peer Review into the previous failed Labour administration and the chaotic end days of the subsequent Liberal Democrat council. This is simply what Liverpool local government looks like.

Multiple Mayors - other cities seem to manage it

We cannot make the mayoral system a scapegoat for a chronic and systemic failure of governance in our city. If, as its critics allege, mayors necessarily lead to an undesirable and dangerous concentration of power, then logically, wouldn’t we also need to seriously revisit our devolution deal and the post of Metro Mayor? Our politicians can’t have it both ways.

And neither should we be spooked by the “too many mayors confuse the voters” line. If it turns out that mayors are a good thing after all, then why should they be rationed? Mayors and Metro Mayors co-exist happily in London, Greater Manchester, South Yorkshire, the West of England, Tees Valley and North of Tyne. Cities in these areas including Bristol, Middlesbrough and Salford appear to be able to cope with the idea of different mayors exercising different powers over different geographic jurisdictions.

We shouldn't of course be surprised that our politicians are advocating for a return to the Leader with Cabinet system, when its most conspicuous difference to the “disgraced” mayoral model is that it would give them the exclusive power to decide who our City Leader should be. Rather than a direct popular mandate, Liverpool’s leader would be entirely beholden to councillors from within their own political group. Only in the looking-glass world of Liverpool politics can this be presented as more democratic and accountable. As the elected Mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees recently argued in response to those advocating abolition of the post there. “It doesn't take much understanding of why the old system didn't work. Anonymous and unaccountable leadership, decisions made by faceless people in private rooms, and a total lack of leadership and action. The mayoral model makes the leader accountable - he/she is elected by the people of Bristol directly, not by 30 people in a room as in the old committee structure.”

If Liverpool votes to abolish its elected mayor and reverts to a system that has already proven unfit for purpose, we will weaken local democracy and diminish accountability.

But this is precisely the brave new system that we will be invited to endorse in next year's referendum and one that has already been tried and found wanting.

The lesson is that having an elected mayor is not a sufficient condition to deliver radical civic and political change, but it is a necessary one. The authority, legitimacy and wider perspective of the mayoral office is vitally important in making our municipal edifice work for the city rather than for itself.

Mayors are a good idea because they provide visible, directly accountable leadership. Their mandate enables them to speak up for their locality with authority and influence. We only need to look to London and Greater Manchester to see how mayors have been powerful and effective advocates for their cities and regions. But ultimately we need one who understands and actually believes in the role, which is why it is difficult to believe that Joanne Anderson's tenure is likely to fulfil the potential that the post could still offer to the people of Liverpool.

But as our councillors understand only too well, mayors are a dangerous idea. Independent candidate Stephen Yip threatened to end party political hegemony in Liverpool with only the meagrest resources and virtually no grassroots organisation. This is an eventuality that establishment politicians must join forces to thwart once and for all.

If Liverpool votes to abolish its elected mayor and reverts to a system that has already proven unfit for purpose, we will weaken local democracy and diminish accountability. And we’ll be doing it in the name of its opposite, bamboozled by the Humpty Dumpty logic of Liverpool politics where words mean whatever our politicians choose them to mean. We will also denying ourselves even the faintest possibility of breaking out from the cycle of dysfunctional party politics.

The elected mayoralty is the only chance we have to change the way our city is run. The tragedy is, we could lose this opportunity before ever having really given it a proper go. Someone needs to start a campaign, and soon.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

Liverpool Bombing: Calls to unite reveal what they really think of us

In the face of a terrorist attack, when much is supposition and information is still filtering in, it’s really important not to rush to judgement. Calm heads should, as in all situations, prevail. However, following the bomb blast from a home-made device in a taxi outside the Liverpool Women’s Hospital, it seems many are doing the complete opposite, crow-barring their agendas into a story that luckily didn’t appear to kill any innocents.

Paul Bryan

In the face of a terrorist attack, when much is supposition and information is still filtering in, it’s really important not to rush to judgement. Calm heads should, as in all situations, prevail.

However, following the bomb blast from a home-made device in a taxi outside the Liverpool Women’s Hospital, it seems many are doing the complete opposite, crow-barring their agendas into a story that luckily didn’t appear to kill any innocents.

One of the more curious examples could be found in Spiked Online in an article entitled ‘David Perry and the incredible heroism of ordinary people’. Speedily jumping onto claims that the taxi driver had quick-wittedly locked his passenger, Emad Al Swealmeen inside the car, after spotting suspicious activity, writer Tom Slater warmed to his task. “Time and again it is the public who are our last line of defence against this barbarism,” he concluded. And that may well be true, but the full facts are not yet clear in this case and Perry’s heroism is yet to be established conclusively. All that we do know at the time of writing, is that the video of the incident clearly shows that the explosion took place before the car had come to a stop. Why don’t we just wait and see and let the police piece it together?

The commentaries that swirl around these events reveal so much about the pre-occupations of those who would form the nation’s opinions. Liverpool’s Metro Mayor, Steve Rotheram was quick to set the tone, issuing a statement which said, “it would seem this was an attempt to sow discord and divisions within our communities. But our area is much stronger than that. We are known for our solidarity and resilience. Our diversity remains one of our greatest strengths. We will never let those who seek to divide us win.”

Merseyside Police Commissioner, Emily Spurrell, obviously had the same briefing sheet, ‘our region is known for its solidarity and resilience,’ she tweeted. Meanwhile, in the Liverpool Echo, Liverpool Mayor, Joanne Anderson was reported to have said, “For all of us who know that Liverpool is a tolerant and inclusive city – this will be hard to come to terms with. Over the next few days, as we learn more about what happened, we must all support each other and unite, as we always do, when times are tough."

Just in case anyone might point the finger, the Liverpool Region Mosque Network issued a statement too, appealing for “calm and vigilance”.

Take note of the consistent themes – tolerance, inclusivity, diversity, solidarity. They’ll be important.