Recent features

Not So Red: Labour’s Slow Rise in the Scouse Republic

Liverpool wasn't always the ultimate Labour stronghold. For much of the past century, Conservatives have dominated local and parliamentary elections. Historian of the Left, David Swift, charts Labour's surprisingly slow rise to power in not-so-red Liverpool.

David Swift

You don’t often see Liverpool compared to Iran. And certainly a stroll through the city centre on a Friday or Saturday night brings sights you probably wouldn’t see in downtown Tehran.

In an essay comparing the politics of Iran and Egypt, the sociologist Asef Bayat pointed out that Egypt, despite having strong popular support for Islamist politics and a weak middle class, never established a religious theocracy along Iranian lines. The difference being that in Iran, the government of the Shah had successfully eliminated all secular opposition – liberals, socialists, trade unionists – so the Mullahs were the only people in a position to take over, despite a lack of broader support for their project. So Egypt had an Islamic movement but not an Islamic revolution, and Iran had an Islamic revolution without much of an Islamist movement.

Over the past 100 years something similar has happened in the political transformation of Liverpool. From a bastion of working-class Toryism, Liverpool has become a city with the five safest Labour seats in the country. Other areas with similar demographics have seen Labour’s support slide in recent years, but in Liverpool the party’s dominance has continued to grow.

Yet curiously, beneath the surface, just like in Iran, the dominant political movement has been anything but strong. Liverpool has undergone this Labour revolution with a much weaker, organised Labour movement than other cities. Don’t believe me? Look at the history.

This year marks the centenary of the election of Jack Hayes, the first Labour MP to sit for a Liverpool constituency – who won the 1923 Edge Hill by-election. This breakthrough came roughly two decades after other ‘Labour heartlands’ such as Manchester, East London, Glasgow, Leeds and South Wales had elected their first Labour MPs.

Before and even after Jack Hayes’ triumph, Liverpool was solidly Tory. From 1885 to 1923, with just a few exceptions, the city’s nine constituencies were won by the Conservative candidate in every parliamentary election. Toxteth was represented by people with little claim to working class roots; people with grand-sounding names such as Henry de Worms and Augustus Frederick Warr. It is hard to imagine now but for 14 years the MP for rugged Kirkdale was a Baronet called Sir John de Fonblanque Pennefather.

The most notable exception to Tory dominance at that time was the Liverpool Scotland constituency, centred on Scotland Road, which was dominated by Irish immigrants. Held by the Irish Nationalist T.P. O’Connor from 1885 until his death in 1929, his victory remains the only time a British parliamentary seat has been won by an Irish nationalist party outside the island of Ireland.

Of course, the Liberals had the occasional reason to celebrate too, winning Liverpool Exchange in 1886, 1887, 1906 and 1910 as well as Liverpool Abercromby in their general election landslide of 1906. But even at that election – a wipeout for the Tories and their worst result until 1945 – the Liberal Party only managed to win two of Liverpool’s nine seats, with the Conservatives taking six out of the other seven.

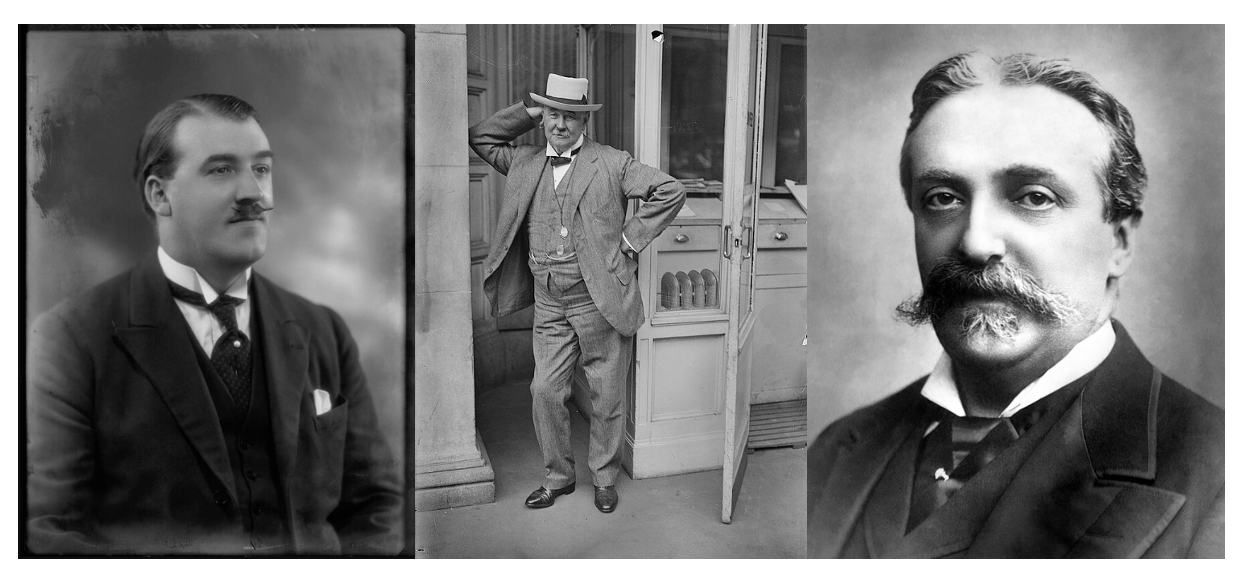

An Irish Republican, Tory Baron and Liverpool’s first Labour MP walk into a bar. But who’s who?

Left to Right: Jack Hayes Labour MP for Edge Hill (1923-31); T.P. O’Connor the Irish Nationalist MP For Liverpool Scotland (1885-1929); and Baron Henry de Worms, Conservative MP for East Toxteth (1885-95). Image credits in respective order (left to right): Bassano Ltd, public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Bain - Library of Congress (1917); Alamy

Some commentators have claimed Liverpool politics are based on rebelliousness or innate defiance and a willingness to speak up and go against the crowd. Which makes what happened in the 1906 general election all the more fascinating. Dominated by the issue of free trade, the Conservatives lost badly at the national level because it was feared their plan to impose tariffs on imported goods would damage trade. And yet even in this election, in a town as totally dependent on trade as Liverpool, even in a port city, Liverpolitans put two fingers up to the national trend and voted for the Tories anyway. Was this an early example of that noted tendency to contrarian defiance or slavish support for the party of power?

Of course, at this time, the six-year-old Labour party was not a serious force around the banks of the Mersey and their leader Ramsay MacDonald – who later become the first Labour Prime Minister, knew it too. In 1910, after a visit to the city he seemed to accept they had no prospects of winning there any time soon, writing with a note of sour grapes that ‘Liverpool is rotten and we had better recognize it’.

Why was Liverpool so slow to support the party of the working class?

One explanation often put forward is the narrowness of the parliamentary franchise which dictated who got to vote. It’s claimed voting restrictions prevented many working people from making their voices heard and it’s certainly true that this affected politics at this time, though perhaps not always in the ways most commonly understood. From 1867, men in ‘borough’ constituencies (usually towns and cities like Liverpool) were able to vote in general elections but only if they were defined as a ‘householder’. This meant a man living independently by himself or with his wife and children who also paid a minimum of £10 a year in rent. In theory, most working-class men could now vote, but in reality it’s estimated 40% of men nationwide were disenfranchised until these rules were relaxed in 1918.

This was because the lack of affordable accommodation meant many men still lived at home with their parents or in houses with multiple families, and so fell foul of the rule. In a port city like Liverpool, where seafaring was the second largest source of employment, this would have been particularly significant because so many men worked away for long periods. The 1921 census found there were twelve times as many men without a fixed address or workplace in Bootle than in St Helens.

Nonetheless, some historians have challenged the idea the franchise disproportionately affected working-class voters, noting that, on average, men from working-class backgrounds found work, left home and started families earlier than their middle-class equivalents. As noted by Neal Blewett in an article for Past and Present, middle-class professionals were more likely to be lodgers, who very often couldn’t vote. It’s too easy to use the disenfranchisement of working-class voters to explain Tory dominance in the city - especially since women, who have tended to favour the Conservatives by wide margins, were unable to vote in general elections until 1918. Perhaps the limitations on the voting franchise hurt rather than helped the Tories. In her influential book, The Iron Ladies (1987), journalist Beatrix Campbell claimed Labour would have won every election between 1945 and 1979 but for women’s right to vote.

The influence of sectarianism overstated

It’s also too easy to blame ‘sectarianism’ for Tory rule in Liverpool. According to this analysis, conflict between Protestants and Catholics divided the working class vote, with Catholics favouring ‘home rule’ for Ireland supporting the Irish Nationalist party (the IPP), while Protestants opposing greater Irish autonomy voted for the Conservatives. The argument goes that the conditions for a Labour breakthrough in Liverpool only occurred after Irish independence in 1922, when the sting went out of the nationalist cause. Catholic votes transferred to Labour, whilst Protestants, with the nationalist issue seemingly resolved, felt less inclined to vote Tory.

But many historians, such as Sam Davies, have downplayed the importance of sectarianism, arguing instead that Tory dominance resulted from the weakness of the Labour party in local politics and splits in the anti-Tory vote.

Famously, Churchill sent gunboats on the Mersey in 1911 to quell a dockers strike, but despite this Liverpool was still voting Conservative. Meanwhile in Glasgow … Red Clydeside was already represented in parliament. Image: HMS Antrim, Ernest Hopkins, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s instructive to compare the political situation in Liverpool to that of Glasgow - another town with a violent sectarian divide. While Liverpool outside of Scotland Road was staunchly Tory, in Glasgow, sectarian sentiment saw a surge in support for the Liberal Party. As far back as 1886, with the Liberal Government led by William Gladstone (a Liverpolitan), proposing Home Rule for Ireland under a less centralised United Kingdom, Catholic voters jumped at the opportunity to get behind the Bill. Nationally, the 1886 general election saw the Liberals lose over 150 seats as the issue proved unpopular. Yet in Glasgow, the Liberals won four of the city’s nine seats – with another two going to the ‘Liberal Unionists’ who, opposing the move, were no doubt supported by the city’s Protestants. Liverpool never saw anything like this degree of sectarian influence.

Back to that 1906 election, which by the way was only the second to be contested by the newly-formed Labour party. While Liverpool was busy voting Tory, in Glasgow, former shipyard worker George Barnes was elected as a Labour MP for Glasgow Blackfriars and Hutchesontown, a seat he held until he was elected for the new Gorbals constituency in 1918, alongside Neil Maclean, who won in Govan. By 1922, Labour was winning ten of the city’s 15 seats. In contrast, no Liverpool constituency elected a Labour MP until after the party had taken most of the seats in Glasgow.

“It is perhaps forgotten today, but back in the interwar years, the largest unions on Merseyside, the TGWU and the National Union of Seamen - representing dockers and sailors – had an inconsistent relationship with the Labour party.”

The importance of skilled workers and Nonconformists

One reason for Labour’s earlier breakthrough in Glasgow was its stronger concentration of skilled trades. Although like Liverpool, a major port, Glasgow relied less on distribution and more on the dominant industry of shipbuilding. This provided a stronger industrial base with many skilled jobs defended by well-organised trade unions. Even if we include the Cammel Laird shipyards in nearby Birkenhead, Liverpool never had a similar level of manufacturing jobs. There was far too much reliance on low-skilled, casual labour which was a lower priority for the wider trade union movement.

At this time, areas that voted Labour had either strong trade unions, or high levels of Nonconformist Protestants such as Baptists, Methodists, Quakers – or both. You can see this trend in places like South Wales, West Yorkshire, East Lancashire, and the Durham coalfield. Nonconformity was linked with moral and political liberalism: Nonconformists such as William Wilberforce had been prominent anti-slavery advocates, and were over-represented among critics of British imperialism. They also challenged elements of the British establishment such as the Church of England and the House of Lords. In Liverpool, however, the trade unions were small or weak, whilst most people were Catholics or Anglicans, with few Protestant Nonconformists.

It is perhaps forgotten today, but back in the interwar years, the largest unions on Merseyside, the TGWU and the National Union of Seamen - representing dockers and sailors – had an inconsistent relationship with the Labour party. In 1927, the Executive Committee of the Liverpool Labour Party (then known as the Liverpool Trades Council and Labour Party) was formed from clerks, postal workers, electricians, engineers, railwaymen, painters and insurance workers. Dressmakers, shop assistants, clerical workers, tailors and garment workers were all well represented in the membership – but representatives from the two dominant occupations in the city were conspicuous by their absence.

Tories still strong after World War 2 and the politics of normal

Even after the 1945 Labour landslide, the Conservatives continued to win elections in Liverpool. Tory MPs were elected for Walton and West Derby until 1964, and for Wavertree and Garston until 1983. At the 1959 local elections, six of Liverpool’s nine council wards were controlled by the Conservatives, and three of those were solidly working-class areas, including Toxteth and Walton.

During the 1970s, control of the council swung between the Tories and Liberals. When the Trotskyist Militant Tendency took over in 1983, they succeeded a Conservative-Liberal coalition.

When Labour was successful on Merseyside in this period it was not because of a strong local labour movement, but because political sentiment was tracking with the ‘normal’, with the city tending to vote in line with national trends

Speaking to political scientist David Jeffery, who studies electoral politics in Liverpool, he told me that after the Second World War there was a general trend towards the ‘nationalisation of politics’. By this he means that national rather than local issues became key determinants in deciding how to vote. Local politics began to matter a lot less, so the Liverpool vote tracked the national vote share. As elsewhere in the country, the party in power nationally would usually suffer in local elections.

As Jeffery explained, the Tory successes in council elections during the late 1960s were not driven by a surge in support for the Tories, but rather a collapse in the Labour vote due to the growing unpopularity of Harold Wilson’s Labour government in Westminster.

Then in the early 1970s, when Ted Heath’s Conservative government was unpopular, Labour and the Liberals did better in local elections, and in 1998, a year after Tony Blair’s Labour landslide, the Liberal Democrats once again took power of Liverpool City Council.

Prone to takeover – the problem with Labour’s low local membership

Even though there was a real change of the political culture and identity of the city in the 1980s, there was still not much of a labour ‘movement’. One of the reasons Militant was able to take over Liverpool Labour was because the local Labour party branches had relatively few members. They’d become hollowed out and simply didn’t have enough people to buttress against a well-organised and well-motivated sect.

Historically, in areas without strong trade unions there would be relatively few people in the local Labour party – put simply if you were not a union member or close to a union member you were far less likely to get involved with Labour. So once the unions lost their strength and influence from the 1980s onwards, alongside a decline in local government, the traditional working class routes into local politics dried up. Membership of Labour constituency branches (CLPs) in traditional working class areas has been on the slide ever since. As an example, the biggest constituency Labour parties today such as Hornsey and Wood Green in London have over 3,000 members, but one of Liverpool’s largest, Liverpool Walton, claims to have just over one thousand, and that might have been at the height of the Jeremy Corbyn membership surge.

One of the reasons Militant was able to take over Liverpool Labour was because the local Labour party branches had relatively few members. They’d become hollowed out and simply didn’t have enough people to buttress against a well-organised and well-motivated sect.

Just as in the early twentieth century, Liverpool today has a large working-class population, but it doesn’t have much of a labour movement – despite Labour consistently winning elections.

There have been well-supported social justice movements: such as during the dock strike of 1995-1998, the Hillsborough Justice Campaign, and more recently grassroots initiatives such as Fans Supporting Foodbanks. But this hasn’t translated into high membership or engagement with the Labour party itself.

Middle-class activists and the politics of identity

Labour’s membership surged under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn from just 198,000 in 2015 to 564,000 by 2017. But how many of these new members were from traditionally working class communities? Creative Commons C.C.0 1.0 via Wikimedia.

As far back as Tony Blair, commentators have noted how the ‘Islington set’ have become increasingly influential in the politics of the Labour party. People whose personal circumstances had taken them a long way from the traditional Labour voter were now shaping the party’s direction. During Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership in the 2010s, membership of the party grew, but often those new members were not from the traditional voter base. London, by comparison to Liverpool, has far higher levels of middle-class graduates and these are exactly the kind of people who have historically joined political parties. It’s not surprising that in places with more middle class voters, there’s been increased enthusiasm and engagement with Labour. But back in the Labour heartlands, not so much. This relative lack of enthusiasm and political engagement can be seen by comparing the turnouts of the last mayoral races in Liverpool and London: in both cases, everyone knew that the Labour candidate would win, yet in London the turnout was 40%, in Liverpool it barely reached 30%.

In recent years, the Liverpool Left has become more radical on cultural issues such as race and ethnicity - but it’s doubtful whether the city’s population is as liberal as their representatives on these issues.

The website, Electoral Calculus breaks down the demographics and political culture of each of the UK’s 650 constituencies, and ranks them according to their political opinion on economics (Left versus Right), internationalism (Global versus National) and culture (Liberal versus Conservative). It then uses cluster analysis to identify the influence of one of seven ‘Tribes’ in each constituency - including ‘Progressives’, ‘Traditionalists’, ‘Centrists’, ‘Kind Young Capitalists’, ‘Somewheres’, ‘Strong Left’ and ‘Strong Right’. It also estimates how each constituency seat voted in the Brexit referendum, a much finer grain of breakdown than exists in the official statistics.

Let’s take a look at how it assesses Liverpool’s five safest Labour seats:

Liverpool Walton - Traditionalist

27 degrees Left, 3 degrees Globalist and 1 degree Conservative; 52% voted Leave.

Knowsley - Traditionalist

26 degrees Left, 2 degrees Globalist, 2 degrees Conservative; 52% voted Leave.

Bootle - Traditionalist

25 degrees Left, 3 degrees Globalist, 0 degrees Social; 50% voted Leave.

West Derby - Traditionalist

26 degrees Left , 6 degrees Global, 1 degree Liberal; 48% voted Leave.

Liverpool Riverside – Strong Left

21 degrees Left, 29 degrees Globalist and 18 degrees Liberal; 27% voted Leave.

As you can see, the top four constituencies are classed as ‘Traditionalists’, according to the Electoral Calculus formula. The people in these seats have, on average, left-wing economic views but cultural and social views that are centrist or conservative.

Traditionalist Kirkby. Small ‘c’ conservatism may rule when it comes to social and cultural views in many of the region’s Labour constituencies. Image Kirkby High Street (2023) by Paul Bryan

In a recent study into how local identities impact on voting behaviour in the Liverpool City Region, David Jeffery also found that while Liverpool constituencies are in the bottom quarter nationally in terms of pro-monarchy sentiment, they are still more pro than anti-monarchy. He found that only 18% of Liverpudlians feel ‘only Scouse’, just 5 percentage points higher than the 13% who feel ‘only English’, with the rest feeling some mixture of Scouse and English.

What can we read into this?

It appears that despite the victories of the Labour party in parliamentary and local elections, there is a large amount of small ‘c’ socially conservative sentiment in the city. That is why up to three constituencies likely voted Leave, and why UKIP came third in the 2014 local elections – only 969 votes off the Greens in second place. They did especially well in working-class wards such as Club Moor, County, Fazakerley, and Norris Green.

This data suggests there’s a risk of Liverpool Labour overreaching on culture, as happened recently with the Scottish National Party (SNP). Despite Scotland’s population being slightly more sceptical on trans rights than the UK average, the SNP leadership assumed they could push forward with radical gender policies - an approach which led to Kate Forbes, who opposes same-sex marriage, coming within 3,000 votes of winning the party’s leadership election.

Within the past year, the SNP has gone from looking invulnerable to now polling only 1% ahead of Labour. Obviously this has not all been down to overplaying their hand on cultural issues, but nonetheless it’s a salutary warning for Liverpool Labour about the dangers of hubris, and mistaking the transformation in the politics of the city for a transformation in its culture.

In the hundred years since the election of the city’s first Labour MP, Liverpool’s support for Labour appears stronger than ever. But history suggests an unpopular Starmer government and continued chaos at the municipal level could well see the party lose power locally and for the majorities of the city’s MPs to be chipped away. The city’s current loyalty to Labour cannot be taken for granted, either by national politicians looking to Liverpool for lessons, or by local figures who might mistake voting patterns for political and cultural radicalism.

David Swift is a historian and writer specialising in Left wing activism who has written for publications such as the New Statesman, The Times, Tribune and Unherd. He is the author of three books including A Left For Itself; and The Identity Myth.

His latest book, Scouse Republic? A Personal History of Liverpool, will be published in 2024 by the Little, Brown Book Group.

*Main image created on Stable Diffusion.

Can Liverpool be Liberated from Labour?

From black ops-style campaigns to discredit rival independent candidates by the local Labour Party to the unlikely rise of the ultimately doomed anti-corruption movement, Liberate Liverpool, the city’s local elections proved to be one of the most fiercely contested in years. And then Labour won. Writing for UnHerd on the eve of the election, Liverpolitan Editor Paul Bryan describes the fervid atmosphere of the campaign amongst the hopes and shattered dreams of candidates of all colours.

Local Elections 2023

Paul Bryan

This article by Liverpolitan Editor, Paul Bryan was published by UnHerd on 3rd May 2023 on the eve of the 2023 Local Elections in Liverpool. To read the whole feature visit…

Before Liverpool can bask in the joy of hosting next week’s Eurovision Song Contest, it must first contend with tomorrow’s local elections — and the rounds of mudslinging that have come with it. Take one of Labour’s election pamphlets, pushed through the letterboxes of residents in the south of the city. Disguised under the banner of Garston Resident News, the leaflet mined old social media posts belonging to independent councillor, Sam Gorst, who had been expelled from the Labour Party in December 2021 for associating with Labour Against the Witchhunt, a group opposed to “the purge” of pro-Corbyn supporters for alleged antisemitism.

Under the headline “Sickening”, Gorst was criticised for historic posts in which he called Queen Elizabeth “a useless bitch” and the Jewish former Liverpool Wavertree MP Luciana Berger, who eventually resigned from the party, a “hideous traitor”. The pamphlet also claimed that he lived in a “leafy” area and insinuated that he had jumped the queue on social housing, although that accusation is contested.

But if the intention was to make an opponent look bad, Labour may have shot itself in the foot. A joint statement released by the Liberal Democrats, The Liverpool Community Independents, The Green Party and the Liberal Party described the leaflet as “cynical”, “dishonest” and “shameful”. Their calls for a clean fight, however, have fallen on deaf ears, not least because the mud is being thrown in all directions amid widely reported allegations of Labour corruption and incompetence.

“In cities with a more contested political complexion, one might expect such failures to be severely punished at the ballot box. But this is Liverpool, and ousting Labour is the toughest of political challenges.”

Snippet taken from a Labour election pamphlet disguised under the banner of Garston Resident News,

To read the whole article visit…

https://unherd.com/2023/05/can-liverpool-be-liberated-from-labour/

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Vanished. The city that disappeared from the map

When I was a young child my parents bought me a truly wondrous gift ‐ an illuminated globe of the world. It was a magical object with the power to inspire and enrapture, but it also taught me two important, but hitherto unknown, facts about the world. The first was that my country, Britain, was very small. So small in fact that it was only possible to fit the names of two cities onto this tiny morsel of irradiated pinkness.

Jon Egan

When I was a young child my parents bought me a truly wondrous gift ‐ an illuminated globe of the world. It was a magical object with the power to inspire and enrapture, but it also taught me two important, but hitherto unknown, facts about the world.

The first was that my country, Britain, was very small. So small in fact that it was only possible to fit the names of two cities onto this tiny morsel of irradiated pinkness. The second lesson, that followed ineluctably from the first, was that my city clearly was important. As far as the world was concerned Britain could be adequately represented by only two places – London, its capital, and Liverpool, its global gateway. We were on the map, or at least we were then.

A few years ago, when passing through the John Lewis department store, I stopped to browse at a selection of highly impressive (but sadly not illuminated) globes. Britain remained within its familiar miniscule dimensions, but the cartographers had skilfully managed to inscribe on its terrain the names of not two, but five significant British cities – London, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and Glasgow. It merely confirmed what I had long suspected ‐ we were no longer important.

There is of course a serious point to this parable, and it is that we are not simply absent from physical maps, but also from the conceptual and metaphorical maps that shape policy and influence important decision‐making. Despite the incessant hype to the contrary, data from the Centre For Cities suggests we are making little progress in closing the performance gap with competing and emerging economic centres.

A well‐placed insider described Liverpool as “the city that has forgotten how to conjugate in the future tense.”

We have become peripheral ‐ largely outside the thought processes and priorities of political decision‐makers, investors, media commentators and influencers. Addressing and reversing this process – or putting Liverpool ‘back on the map’ ‐ has been, or certainly should have been, a guiding principle for our political and civic leaders over the last four decades. With a City Council mired in crisis and multiple criminal investigations, and the most recent State of The City Region (2015) report presenting a picture of chronic levels of ill‐health, worklessness and deprivation, it’s clear we still have a very long way to go.

For anyone wondering if the economic picture has improved since that last report was published, check out the tale of woe in the new Shaping Futures report, The Demographics and Educational Disadvantage in the Liverpool City Region (2021).

My own involvement with efforts to reposition and rehabilitate Liverpool’s external image has been deeply frustrating and depressingly circular. When in 2002 Liverpool was bidding to become European Capital of Culture, bid supremo, Bob Scott, suffered a heart attack in the closing stages of the process. City Council CEO, Sir David Henshaw took control of the bid, and invited myself as director of the agency that had devised the bid’s World in One City branding, and the Lib Dem’s political strategist, Bill le Breton, to review the campaign and communication messaging. This was an interesting and instructive exercise. Talking to people very close to the then Culture Minister, Tessa Jowell, and contacts equally close to the leading members of the judging panel, the feedback on Liverpool’s campaign pitch was not entirely encouraging. One of the most memorable comments from a very well‐placed insider described Liverpool as “the city that has forgotten how to conjugate in the future tense.” In a competitive process that was supposedly about regeneration and the role of culture in stimulating economic transformation, Liverpool had, until that point, focused almost entirely on showcasing its “great cultural heritage” and waxing nostalgically about its past glories as the Second City of Empire.

A radical rethink was needed, and fast if the city was to be ready in time for the judges’ second visit. We’d need a whole new bid narrative, rigorously disciplined messaging and a tightly scripted programme to change hearts and minds. The new story would be about the future ‐ a city applying its creative energies to embrace cutting‐edge culture, commerce and technology – and it worked. The only problem was that having won, we quickly abandoned the brave, new language and future‐focused vision. 2008 became, as Phil Redmond, Capital of Culture’s, last‐minute appointee as Creative Director, once testified, the proverbial “Big Scouse wedding” with Uncle Ringo on the karaoke.

Consigned to the second tier of UK cities, Liverpool had somehow become pigeon‐holed as economically and maybe even culturally irrelevant.

Fast forward to 2010 and the festival’s former marketing supremo, Kris Donaldson, arrives back in Liverpool to take up a new position as the city’s Destination Manager, only to discover that the promise of Capital of Culture as a platform to radically re‐position Liverpool had largely been squandered. Research commissioned by economic regeneration company, Liverpool Vision had suggested the city was perceived as quirky and entertaining, but news of its “regeneration miracle” was still a dimly perceived rumour amongst the nation’s influencers and decision‐makers. Without any significant expectation of success, I joined forces with journalist, political campaigner and former BBC Radio Merseyside broadcaster, Liam Fogarty and two local creatives (Jon Barraclough and Chris Blackhurst) to pitch for the city re‐branding brief that emerged from Kris’s sobering discovery. Our proposal was less of a pitch and more an indulgent exercise in provocation. Having initially been sifted out of the process by a dutiful underling at Liverpool Vision, Kris reinstated us onto the shortlist for interview. Our presentation began with a miscellany of quotes from ministerial speeches, broadsheet Op‐Eds and the authoritative musings of a polyglot of professional commentators. They were all opining on the need for economic re‐balancing and the incipient promise of that great new hope, the Northern Powerhouse. But amongst their mountain of words, one city was consistently and depressingly absent, and it was of course, Liverpool.

Permanently consigned to the second tier of UK cities, Liverpool had somehow become pigeon‐holed as economically and maybe even culturally irrelevant. The bold promise of 2008 had been replaced by fatalistic resignation, punctuated by occasional blasts of delusional bombast and mawkish nostalgia. As a result, Liverpool ceased to be discussed when the adults were in the room.

Winning the brief, with an ominous feeling of déjà vu and an almost Sisyphean sense of futility, we set out to equip the city once again with a future tense vocabulary and a story that would surprise and challenge the preconceptions of those we most needed to convince and convert. But like an aging soap star struggling with new scripts and plot lines, the city inevitably lapsed into its well‐worn phrases and crowd‐pleasing clichés. The It’s Liverpool campaign became less of a device to “package surprises” and orientate future ambition, but more an excuse to recycle familiar messages and tell the world what they already knew.

Fast forward another seven years to 2017 and I am sitting in the campaign HQ of the man bidding to become the first Liverpool City Region Mayor, the Labour MP for Walton, Steve Rotheram. We are discussing how to frame a transformational narrative for his soon to be launched election campaign. I find myself agreeing with him that devolution is the last chance saloon for a city (or City Region) being left behind by its competitors and too often ignored by those whose judgments and decisions shape its future. I think we may even have used the phrase “putting Liverpool back on the map” as shorthand for a project to reassert the city’s status as a Premier League player (forgive the clumsy football cliché) ensuring it once again became an integral component in the national economic narrative. I was increasingly hopeful that Steve’s refreshingly insightful analysis of the city’s deficiencies could be the prequal to a visionary devolution project. Four years on, and the consensus is that our Metro Mayor has yet to reset Liverpool’s trajectory or restore our status as an important economic or creative asset for the UK. If devolution was the last chance saloon, then the barman, with one eye on the clock, appears to be reaching ominously for the towels.

Four years on, and the consensus is that our Metro Mayor has yet to reset Liverpool’s trajectory or restore our status as an important economic or creative asset for the UK.

The initial stimulus for this article was the then imminent launch of Rotheram’s re‐election campaign in March 2020, before, of course, normality was put on hold by Covid and what we imagined were urgent political challenges dissolved into irrelevancy in the face of a global human tragedy. That earlier, never published version of this article, drafted in the format of an open letter to the Metro Mayor‐elect, was triggered by a series of events that acted as timely reminders of our reduced circumstances. Former Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne had used his resignation as Chair of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership to restate his vision of a rebalanced Britain where the “great cities of the north” (predictably we weren’t name‐checked) counterbalanced the wealth and prestige of London. But the tipping point for me, however, came on a day when Rotheram launched the latest phase of the Mersey Tidal Energy study, part of his big plan to recast the Liverpool City Region as an exemplar for sustainability and innovation. He might as well as not have bothered for all the attention it got. Instead, on that same day, a Simon Jenkins’ Guardian Op‐Ed calling for economic rebalancing, once again seemed to have been drafted with a map of Northern England where Liverpool was inexplicably absent. Twelve years after Capital of Culture and four years after devolution, the sad fact is that we are still not on the map.

The constructive, and at the time topical, section of the article was a positively motivated attempt to offer some suggestions for Rotheram’s critically important second term. Not that I thought I was especially qualified to provide such advice, but more to help stimulate a bigger, smarter and more diverse political conversation – in fact, the kind of energised democracy that devolution was designed to foster.

In a strange way Covid has given us more time, and an even more urgent imperative to take stock of where our City Region is heading. We need to be more radical, more imaginative and more willing to challenge the myths and shibboleths that have constrained thinking, blighted ambition and stunted potential.

So, in that spirit, here are five ideas about how we might help to remake and re‐position our city.

1. Appoint smart people – preferably from places more successful than Liverpool

Scouse exceptionalism and insularity are tragically compounded by a debilitating public sector culture. As the employer of last resort, our public institutions have evolved a defensive protectionist mindset that all too often fosters inertia and promotes mediocrity. I’m not necessarily advocating a Dominic Cummings‐style cull of staff and an invitation to assorted geeks, weirdos and misfits to replace them, but for devolution to make a difference it needs to be delivered by different people with higher levels of ambition, achievement and creativity. The kind of people capable of imagining possibilities beyond the recently launched hotchpotch of reheated pet projects and lame platitudes which masquerade as the city’s “transformational vision” for a post‐Covid future. What we need more than anything are people with a track record of delivery in a city or City Region that is palpably more successful than Liverpool. To extend the football analogy, we need a Klopp rather than a Hodgson; an Ancelotti or Benitez, not a Big Sam.

Rather than a being a dynamic galvanising body with a transformational agenda, our post‐devolution governance has somehow coalesced into an unhappy amalgam of Merseytravel and the Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) – a stifling bureaucracy with a highly developed aversion to any form of risk or innovation. For the next term to be successful, our Metro Mayor needs to transform the calibre, capacity and orientation of the Combined Authority. It remains to be seen whether the new Head of Paid Service can create a different dynamic and organisational culture or can inculcate the expansive perspective that has thus far been absent from our devolution project.

2. Have a story that makes sense, and then stick to it

Liverpool’s tragedy is that it is famous but no longer important. It means people already have an idea about who we are, what we’re good at and what we’re not so good at – like having an economy. The Combined Authority issued a brief to create a new City Region narrative, but the process seemed to be firmly in the hands of people who were too deeply immersed in the old dispensation, and too easily seduced by trite PR‐speak and marketing gobbledygook. So, here’s a radical suggestion – and one in the spirit of recommendation 1 – let’s appoint a world‐class creative with an international reputation to help us frame and articulate what this City Region is about. There are extraordinary flowerings of innovation and excellence here, but they currently look more like an advent calendar than a big picture. Rather than designing another procurement process and issuing yet another brief, why don’t we appoint somebody of the calibre of Bruce Mau, the Canadian branding and design genius? Let’s get a fresh set of eyes to re‐imagine the planet’s first “World City” and the place that globalised popular culture. Unless we can answer the existential question – what is Liverpool for? – we cannot hope to persuade people that we are still relevant today.

3. Get out there and spread the message

OK, I understand the electoral context and the reason why it was attractive for Steve Rotheram to launch the Tidal Energy study ‐ and a raft of more recent policy announcements ‐ in his own back yard, but guess what? No‐one east of Newton‐le‐Willows is taking any notice. The world is not watching or listening to Liverpool, so we need to get out there and tell them. That means doing the big announcements in London or wherever they’ll get noticed. It means having a Metro Mayor who is prepared and confident to do the awkward, challenging and high‐risk national media gigs. It means being willing to get on planes and fly to the four corners of the earth to spread the Liverpool (City Region) message. The great thing about not being weighed down with a plethora of statutory and service delivery responsibilities, is that a Metro Mayor can be our foreign minister, our ambassador – the kind of advocate and propagandist that this place has lacked and still so badly needs.

4. Find the causes and campaigns that make the story sticky and believable

As Boris Johnson so ruthlessly demonstrated in the Brexit and General Election campaigns, the world, the media ‐ and especially social media ‐ abhor complexity. Messages need to be sharp, self‐explanatory and sticky. They need to reveal and illuminate the bigger picture, and have the power to vanquish the myths, clichés and stereotypes that continue to blight perceptions of the City Region. We need to be able to definitively answer some key questions. What are the three most important ideas that can be the foundation of a new economic identity that gives our City Region a competitive edge and compelling new story? How do they connect? Who will they effect and why is it absolutely vital and non‐negotiable that we deliver on them? Whatever these ideas prove to be, underpinning them is a very simple ambition; to make Liverpool not just relevant, but also important – somewhere that is vital to the vision of a rebalanced, prosperous and successful UK.

5. Look for short cuts – if necessary, borrow someone else’s reputation and influence

It’s possibly the quickest win and the hardest pill to swallow, but we do have one big asset on our doorstep that could and should be mobilised to our advantage. George Osborne once observed that Manchester and Leeds city centres are closer to each other than the two ends of London’s Central tube line. Perhaps, from the distant vantage point of the Evening Standard editor’s office, he is unable to see the inconveniently positioned mountains or the fact that Liverpool and Manchester are even closer together! We even share two centuries of economic interdependence, and between us possess all of the attributes that sociologist, Saskia Sassen identifies as the defining characteristics of a global city. Abandoning football terrace rivalry to position Liverpool City Region closer to its burgeoning neighbour is both logical and necessary. An integrated transport authority, a shared policy unit and a merged LEP are all ways in which Liverpool City Region could begin to reposition itself within an expanded urban economy with the scale and asset base to counter‐balance London. Let’s not be constrained by redundant mindsets or arbitrary administrative boundaries. Liverpool – and Birkenhead – more than anywhere else can claim to have invented the template for modern civic governance in Britain, so why not pioneer new and liberating models designed to deliver the levelling‐up economic agenda, that will otherwise remain pious rhetoric?

Of course, these suggestions were offered in the confident expectation that the Metro Mayoral election was a mere procedural formality. Not even the implosion of Mayor Joe Anderson’s city mayoralty, the Caller Report and the national party investigation into Liverpool Labour were able to dent Rotheram’s majority. Labour’s almost Belarussian control of the City Region, and the fatalistic impotence of a fractured opposition, leaves us with a hollowed‐out politics where, notwithstanding the heroic efforts of Independent candidate Stephen Yip, the impetus for an inclusive civic discourse is blunted by establishment complacency and partisan insularity. A competitive electoral democracy, intelligent media scrutiny and strong independent civic voices (rather than meek subservience to the local state) are the prerequisites for energised politics and the possibility of a visionary civic project. So maybe the big question isn’t simply about what Steve Rotheram and Joanne Anderson need to do next, but how do we make space for genuinely transformational alternatives that might help Liverpool regain its former economic prestige and put us back on the map.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.