Recent features

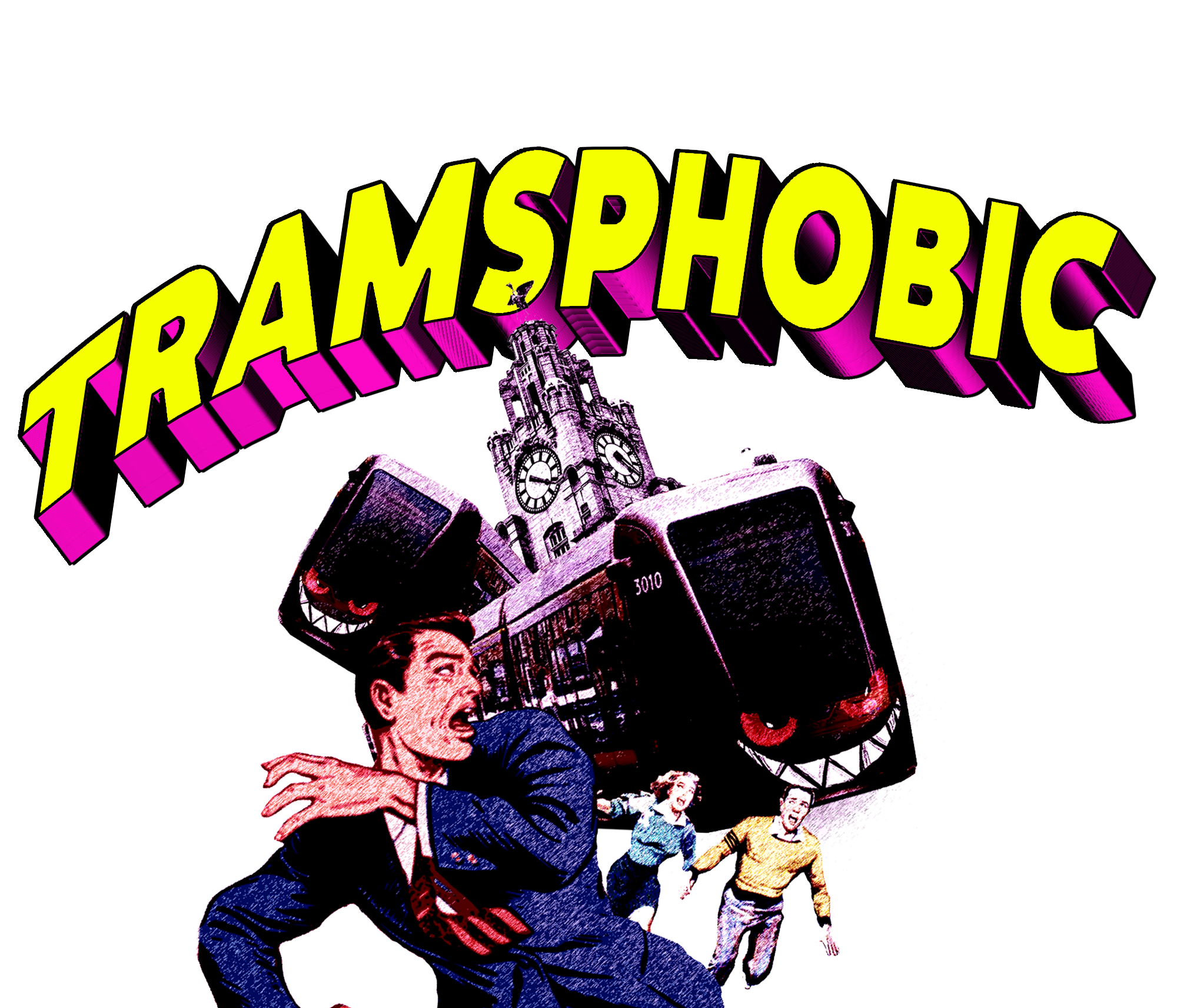

Trams-phobia. Time to face our fear of light rail

The embarrassing history of Liverpool’s abortive Merseytram project put the fear of God into city leaders, rendering any discussion of light rail a taboo subject never to be whispered in the corridors of power. It’s a sorry tale with many twists and turns, but is it time to get over it? Could trams still offer a solution to the city’s transport blackspots?

Prof. Lewis Lesley

Liverpool’s status at the point of embarkation for the first inter-city train journey is well acknowledged and celebrated, but it’s also the case that our city region (or Birkenhead to be more precise) was the location for Britain’s first ever urban tramway in 1860.

Trams continued to be a major means of transit and connectivity across the City Region until the late 1950s. The rise of personalised motor vehicles and the desire of drivers for unimpeded priority over cumbersome fixed-track trams, led to their gradual replacement by diesel buses across the UK and many other countries.

In recent decades there has of course been a growing awareness that ever increasing car use has presented its own set of problems including poor air quality, congestion, fatalities and injuries arising from crashes, not to mention the motor vehicle’s not inconsiderable contribution to global warming. The desire to rebalance cities, reduce congestion and pollution and prioritise sustainable transport modes, has led to a major renewal of interest in trams as a key component in cleaner and more efficient urban transit. Today, Manchester, Sheffield, Birmingham, Nottingham, Edinburgh and Bristol are amongst the cities that either have or are planning to introduce integrated tram networks as part of their urban transport system.

So why not Liverpool? Light Rail systems (trams on tracks) are not only not under active consideration, but they have become a taboo subject never to be whispered in the corridors of power. Why is this the case, and shouldn’t proper consideration be given to the contribution that trams could make to addressing some of our most acute transport and environmental policy challenges?

Let me start by declaring an interest. I am not only an expert advocate for trams, but I played a key role in promoting a tram system for Liverpool between the city centre and John Lennon Airport in the 1990s. The project had a number of notable and attractive features; lightweight trams and track would have been a less intrusive and costly option to the system then being installed with great fanfare in Manchester. But perhaps its most significant component, at least as far as the public decision-makers were concerned was that it was to be delivered and financed entirely by the consortium's lead partner, PowerGen.

The repercussions of the Merseytram fiasco were enough to make trams a toxic subject and a trauma that no local politician ever wanted to revisit.

Private investment in Liverpool has, alas, never been an uncontentious or universally welcomed proposition. The idea that a private company should physically install as well as operate a modern transport system was perhaps ahead of its time, and considered something of an affront to the teams at Merseytravel and Liverpool City Council. Their preferred option was something called the Merseyside Rapid Transit System - effectively guided buses - which was ultimately thrown out by the Secretary of State for Transport. Despite its comparative drawbacks, its status as an approved Merseytravel scheme ensured that our consortium's proposals received less than perfunctory consideration and planning permission was refused. Unlike trams that operate on dedicated track, MRTS would have operated on existing roads, competing for space and priority with other road users. Without dedicated road space and right of way priority even the modern incarnation of "trackless trams," with their sleek train-like appearance - designed to overcome the "trams are sexy, buses are boring perception" - are a poor second best solution. Steel traction always provides a better ride and passenger experience than rubber on tarmac.

Some years passed. By 2005, even Merseytravel had embraced the tram concept.

Fig 1: Merseytram’s proposed 3-line network

A three line network was proposed with routes from Liverpool city centre to Kirkby, Prescot and Whiston and the airport. But the project was doomed to failure and it’s a sorry tale with many twists and turns. Project costs spiralled amid delays, accusations of poor value for money, arguments over which routes should be prioritised, as well as reported management failures at Merseytravel as outlined in a damning 53-page report by District Auditor, Judy Tench.

Relationships between the transport authority and councils, who were responsible for providing a not insignificant chunk of the now £325m budget for Line One, proved challenging and buy-in was never firmly established. Merseytravel spent £70m on consultancy fees, land acquisition, design, initial engineering and steel for the tracks without ever getting final sign-off from the Treasury. The government watched on as Merseytram morphed from a transport project into a local political football.

Senior management at Merseytravel blamed “rogue officials” at the City Council such as CEO David Henshaw for undermining the project, claiming he was leaking information to the Department for Transport, which chipped away at the government’s confidence. The City Council saw it another way believing the project was an impertinent and poorly managed imposition on their turf by Merseytravel. In the face of political rows, planning wrangles and the absence of unequivocal local political support, the government’s patience wore out. Despite being granted full planning approval at a Public Inquiry, the prospect of ongoing squabbles between the City Council and Merseytravel, ultimately resulted in the withdrawal of funding by the then Transport Minister, Sadiq Khan.

Merseytravel spent £70m on consultancy fees, land acquisition, design, engineering and steel without ever getting final sign-off from the Treasury. Merseytram had morphed from a transport project into a local political football.

Interestingly, the decision to prioritise the Kirkby route over the more obviously strategic and commercially viable route to Liverpool airport, was one of the reasons why Merseytram lost the crucial support of the City Council in the first place. The Kirkby route scored higher in terms of regeneration and social value attracting higher capital grant support from central government but it came at greater financial risk to the local authorities and they were reluctant to jump in. In the end, the only thing the city had to show for it was substantial debts, embarrassed red faces, and a stack of unnecessary compulsory purchase orders on private property. Sadly, the repercussions of the Merseytram fiasco, including the selling off of the unused steel rails for a third of their original purchase price was enough to make trams a toxic subject and a trauma that no local politician ever wanted to revisit.

In the intervening years, trams have been introduced into other major cities with great success and growing public popularity. Yet Liverpool, burned by its past experiences, has shied away from taking a fresh look at the subject and has avoided initiating any kind of study or research to evaluate the potential benefits or contribution of light rail to the region’s future transport needs.

But can we really allow political embarrassment to preclude consideration of a transport option that in 2005 was recognised as an inherently good idea? As late as 2012 Liverpool Vision’s Strategic Investment Framework (SIF) embraced the need for a direct rapid transit link to Liverpool Airport, which was once again addressed in our 2015 Trampower proposal.

So what are the potential benefits of a tram system for Liverpool City Region and how might it help us to solve some of our most pressing policy challenges?

1. Trams are clean and green

During the first Covid lockdown, reductions in car traffic realised an enormous and immediate improvement in air quality, but car use is now already back to pre-Covid levels, whilst public transport patronage is only at half its former level. Transport is the main source of toxic air pollution and in a city where more than 60% of all journeys are by car, motor vehicles bear a massive responsibility for the estimated 1,040 annual deaths in the city region arising from bronchial and cardio illnesses attributable to poor air quality. Reducing car use and promoting modal shift towards public transport would make a substantive contribution to improving air quality and ensuring fewer illnesses and deaths.

Similarly, cars are a huge source of CO2 emissions locally and globally. The recent COP26 summit in Glasgow drew up plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to zero by 2050 to avert the worst consequences of global warming. Liverpool City Region has adopted an ambitious Climate Action Plan and aims to be carbon neutral before 2040. This will necessitate a comprehensive reappraisal of transport policies, beyond its current rail investment and bus re-regulation plans, to achieve modal shift and reduce private car use. Whilst electric cars produce no CO2 they do create carcinogenic micro particles from tyres and tarmac. Meanwhile, the effectiveness of their contribution to CO2 reduction depends significantly on how quickly people make the switch from diesel and petrol, which in turn will be influenced by the availability of charging points. So, notwithstanding the environmental benefit of electric cars, they are not going to provide the magic bullet. Promoting modal shift where possible to reduce congestion and pollution should encompass consideration of sustainable transport modes, including trams.

2. People like trams

Where trams have been introduced in other UK cities they have resulted in a significant shift from private car use to public transport with roughly a quarter of users attracted away from their cars. According to a study by the Passenger Transport Executive Group it was estimated that the first wave of tram systems in the UK led to an annual reduction of 22 million car journeys, with more recent studies suggesting this figure is now nearer to 60 million.

Trams are reliable, they run to predictable timetables and are three times more energy efficient than buses. There is also significant evidence that they are perceived as more modern, aspirational and attractive to commuters who would be unwilling to switch to buses. The introduction of the Luas tram system in Dublin was instrumental in ensuring that two thirds of all journeys into the city centre are now via public transport, compared to only a quarter in Liverpool. Attitudinal studies in Dublin revealed that many tram users from the more affluent suburbs would never contemplate bus use.

A Department for Transport Survey in 2019 showed that tram passengers gave a 90% approval rating, because trams are 90% reliable, as well as 73% always finding space and 70% agreeing tram fares are good value for money.

3. Trams make quicker connections between neighbourhoods and centres of employment

As recognised by the 2015 Liverpool Vision SIF a direct rapid transport link to

Liverpool John Lennon Airport remains a fundamental necessity. We are one of the few UK or major international cities without such a link, and extending the rail connection from South Parkway is neither practicable in terms of land availability nor affordable. Trampower has demonstrated the viability and affordability of a tram link to John Lennon Airport which would also serve key retail and employment sites as well as residential neighbourhoods not currently served by Merseyrail. The detailed scoping and feasibility work undertaken by Trampower envisaged a tram every six minutes, and a journey between the airport and city centre taking about half an hour, with a high level of reliability thanks to traffic-free tram reservations for nearly half the route, and ‘green wave’ priority traffic management for the rest.

Trams and streetcars have also been mooted as a means of improving connectivity to emerging, but currently disconnected employment areas like Liverpool’s Knowledge Quarter and Wirral Waters. Whether these are stand-alone solutions or part of an integrated city region network, the proposals acknowledge the value and popularity of trams as a means of getting large numbers of people from A to B within a dynamic urban environment. With one line operational, additional lines can be added on a marginal cost basis, so strengthening otherwise weak financial cases.

4. Trams are more affordable and cost effective

Whereas extending Merseyrail from South Parkway to the airport may seem like a preferable option, for the volume of passengers involved, it would simply be uneconomic. Despite the Chancellor’s substantial, recent £710m transport grant to the Metro Mayor, there is limited scope to significantly extend metro rail infrastructure across the city region due to its intrinsic cost. As one senior transport practitioner observed, trams cost 10% of a metro rail system and deliver 90% of the benefits. So a tramway could therefore be a cost effective solution, and serve communities along the route very well. Focusing on the priority route to Liverpool Airport, Trampower identified at least 60 possible routes and combinations, many following old tram lines which utilised the central reservations of boulevards in the south of the city. In addition, there is already space allocated at the Liverpool One bus terminus for trams dating from the failed Merseytram project.

Combining lighter, newer CityClass Mk2 trams with a low profile “no dig – glue in the road” track system would further reduce the cost and time of installation in streets, and provide work for British Steel to roll LR55 rails, saving on imports. LR55 has been in use in Sheffield for over 25 years without needing any maintenance.

5. Trams deliver investment and regeneration

Trams bring investor confidence, as demonstrated in Croydon, Manchester, Nottingham and wherever they have been installed. This means that development is attracted to locations close to tramways, benefiting from the improved quality of service offered with enhanced accessibility and reliability. Research published by Lloyds Bank looking at the effect of tram systems in Manchester, Birmingham and Edinburgh revealed that house prices rose by 12% compared to average rises in unserved parts of those cities. More generally, trams are seen as a visible sign of investment, ambition and modernity, boosting civic pride and confidence and helping to attract tourism. Manchester’s civic leaders have cited the Metrolink tram system as one of the pivotal investments that transformed perceptions of the city.

In conclusion, trams are clean, green, efficient and affordable. They deliver outputs that are hard to replicate through comparable investment in rail or bus. It’s not the purpose of this article to insist our city region embraces the tram now, but we should be willing to put it in the mix and to evaluate their potential contribution to meeting future transport, regeneration and environmental challenges. It's time for our Metro Mayor to signal a new era, and a willingness to consider ideas and proposals emanating from outside the closed circle of public sector policy makers - still seemingly traumatised by the Merseytram experience. It's time to take another look at trams.

Professor Lewis Lesley is an acknowledged expert in urban public transport. Formerly Professor of Transport Science at Liverpool John Moores University, he is also the author of the Light Rail Developers’ Handbook. As Technical Director at Trampower Ltd, he provides consultancy on the design and development of light rail technology.