Recent features

Not So Red: Labour’s Slow Rise in the Scouse Republic

Liverpool wasn't always the ultimate Labour stronghold. For much of the past century, Conservatives have dominated local and parliamentary elections. Historian of the Left, David Swift, charts Labour's surprisingly slow rise to power in not-so-red Liverpool.

David Swift

You don’t often see Liverpool compared to Iran. And certainly a stroll through the city centre on a Friday or Saturday night brings sights you probably wouldn’t see in downtown Tehran.

In an essay comparing the politics of Iran and Egypt, the sociologist Asef Bayat pointed out that Egypt, despite having strong popular support for Islamist politics and a weak middle class, never established a religious theocracy along Iranian lines. The difference being that in Iran, the government of the Shah had successfully eliminated all secular opposition – liberals, socialists, trade unionists – so the Mullahs were the only people in a position to take over, despite a lack of broader support for their project. So Egypt had an Islamic movement but not an Islamic revolution, and Iran had an Islamic revolution without much of an Islamist movement.

Over the past 100 years something similar has happened in the political transformation of Liverpool. From a bastion of working-class Toryism, Liverpool has become a city with the five safest Labour seats in the country. Other areas with similar demographics have seen Labour’s support slide in recent years, but in Liverpool the party’s dominance has continued to grow.

Yet curiously, beneath the surface, just like in Iran, the dominant political movement has been anything but strong. Liverpool has undergone this Labour revolution with a much weaker, organised Labour movement than other cities. Don’t believe me? Look at the history.

This year marks the centenary of the election of Jack Hayes, the first Labour MP to sit for a Liverpool constituency – who won the 1923 Edge Hill by-election. This breakthrough came roughly two decades after other ‘Labour heartlands’ such as Manchester, East London, Glasgow, Leeds and South Wales had elected their first Labour MPs.

Before and even after Jack Hayes’ triumph, Liverpool was solidly Tory. From 1885 to 1923, with just a few exceptions, the city’s nine constituencies were won by the Conservative candidate in every parliamentary election. Toxteth was represented by people with little claim to working class roots; people with grand-sounding names such as Henry de Worms and Augustus Frederick Warr. It is hard to imagine now but for 14 years the MP for rugged Kirkdale was a Baronet called Sir John de Fonblanque Pennefather.

The most notable exception to Tory dominance at that time was the Liverpool Scotland constituency, centred on Scotland Road, which was dominated by Irish immigrants. Held by the Irish Nationalist T.P. O’Connor from 1885 until his death in 1929, his victory remains the only time a British parliamentary seat has been won by an Irish nationalist party outside the island of Ireland.

Of course, the Liberals had the occasional reason to celebrate too, winning Liverpool Exchange in 1886, 1887, 1906 and 1910 as well as Liverpool Abercromby in their general election landslide of 1906. But even at that election – a wipeout for the Tories and their worst result until 1945 – the Liberal Party only managed to win two of Liverpool’s nine seats, with the Conservatives taking six out of the other seven.

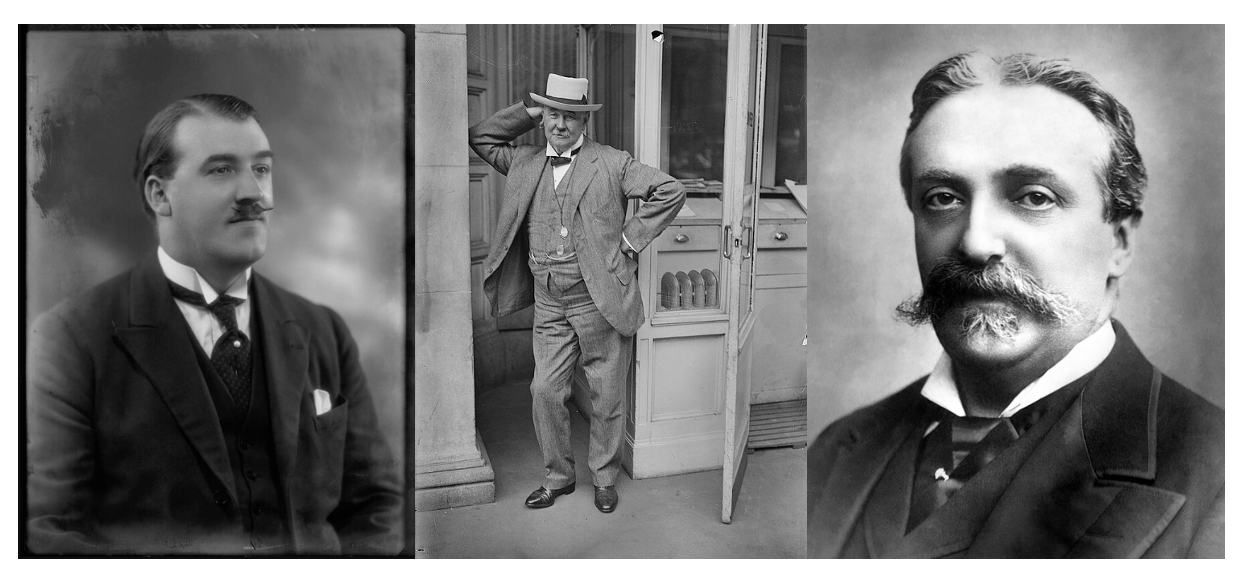

An Irish Republican, Tory Baron and Liverpool’s first Labour MP walk into a bar. But who’s who?

Left to Right: Jack Hayes Labour MP for Edge Hill (1923-31); T.P. O’Connor the Irish Nationalist MP For Liverpool Scotland (1885-1929); and Baron Henry de Worms, Conservative MP for East Toxteth (1885-95). Image credits in respective order (left to right): Bassano Ltd, public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Bain - Library of Congress (1917); Alamy

Some commentators have claimed Liverpool politics are based on rebelliousness or innate defiance and a willingness to speak up and go against the crowd. Which makes what happened in the 1906 general election all the more fascinating. Dominated by the issue of free trade, the Conservatives lost badly at the national level because it was feared their plan to impose tariffs on imported goods would damage trade. And yet even in this election, in a town as totally dependent on trade as Liverpool, even in a port city, Liverpolitans put two fingers up to the national trend and voted for the Tories anyway. Was this an early example of that noted tendency to contrarian defiance or slavish support for the party of power?

Of course, at this time, the six-year-old Labour party was not a serious force around the banks of the Mersey and their leader Ramsay MacDonald – who later become the first Labour Prime Minister, knew it too. In 1910, after a visit to the city he seemed to accept they had no prospects of winning there any time soon, writing with a note of sour grapes that ‘Liverpool is rotten and we had better recognize it’.

Why was Liverpool so slow to support the party of the working class?

One explanation often put forward is the narrowness of the parliamentary franchise which dictated who got to vote. It’s claimed voting restrictions prevented many working people from making their voices heard and it’s certainly true that this affected politics at this time, though perhaps not always in the ways most commonly understood. From 1867, men in ‘borough’ constituencies (usually towns and cities like Liverpool) were able to vote in general elections but only if they were defined as a ‘householder’. This meant a man living independently by himself or with his wife and children who also paid a minimum of £10 a year in rent. In theory, most working-class men could now vote, but in reality it’s estimated 40% of men nationwide were disenfranchised until these rules were relaxed in 1918.

This was because the lack of affordable accommodation meant many men still lived at home with their parents or in houses with multiple families, and so fell foul of the rule. In a port city like Liverpool, where seafaring was the second largest source of employment, this would have been particularly significant because so many men worked away for long periods. The 1921 census found there were twelve times as many men without a fixed address or workplace in Bootle than in St Helens.

Nonetheless, some historians have challenged the idea the franchise disproportionately affected working-class voters, noting that, on average, men from working-class backgrounds found work, left home and started families earlier than their middle-class equivalents. As noted by Neal Blewett in an article for Past and Present, middle-class professionals were more likely to be lodgers, who very often couldn’t vote. It’s too easy to use the disenfranchisement of working-class voters to explain Tory dominance in the city - especially since women, who have tended to favour the Conservatives by wide margins, were unable to vote in general elections until 1918. Perhaps the limitations on the voting franchise hurt rather than helped the Tories. In her influential book, The Iron Ladies (1987), journalist Beatrix Campbell claimed Labour would have won every election between 1945 and 1979 but for women’s right to vote.

The influence of sectarianism overstated

It’s also too easy to blame ‘sectarianism’ for Tory rule in Liverpool. According to this analysis, conflict between Protestants and Catholics divided the working class vote, with Catholics favouring ‘home rule’ for Ireland supporting the Irish Nationalist party (the IPP), while Protestants opposing greater Irish autonomy voted for the Conservatives. The argument goes that the conditions for a Labour breakthrough in Liverpool only occurred after Irish independence in 1922, when the sting went out of the nationalist cause. Catholic votes transferred to Labour, whilst Protestants, with the nationalist issue seemingly resolved, felt less inclined to vote Tory.

But many historians, such as Sam Davies, have downplayed the importance of sectarianism, arguing instead that Tory dominance resulted from the weakness of the Labour party in local politics and splits in the anti-Tory vote.

Famously, Churchill sent gunboats on the Mersey in 1911 to quell a dockers strike, but despite this Liverpool was still voting Conservative. Meanwhile in Glasgow … Red Clydeside was already represented in parliament. Image: HMS Antrim, Ernest Hopkins, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s instructive to compare the political situation in Liverpool to that of Glasgow - another town with a violent sectarian divide. While Liverpool outside of Scotland Road was staunchly Tory, in Glasgow, sectarian sentiment saw a surge in support for the Liberal Party. As far back as 1886, with the Liberal Government led by William Gladstone (a Liverpolitan), proposing Home Rule for Ireland under a less centralised United Kingdom, Catholic voters jumped at the opportunity to get behind the Bill. Nationally, the 1886 general election saw the Liberals lose over 150 seats as the issue proved unpopular. Yet in Glasgow, the Liberals won four of the city’s nine seats – with another two going to the ‘Liberal Unionists’ who, opposing the move, were no doubt supported by the city’s Protestants. Liverpool never saw anything like this degree of sectarian influence.

Back to that 1906 election, which by the way was only the second to be contested by the newly-formed Labour party. While Liverpool was busy voting Tory, in Glasgow, former shipyard worker George Barnes was elected as a Labour MP for Glasgow Blackfriars and Hutchesontown, a seat he held until he was elected for the new Gorbals constituency in 1918, alongside Neil Maclean, who won in Govan. By 1922, Labour was winning ten of the city’s 15 seats. In contrast, no Liverpool constituency elected a Labour MP until after the party had taken most of the seats in Glasgow.

“It is perhaps forgotten today, but back in the interwar years, the largest unions on Merseyside, the TGWU and the National Union of Seamen - representing dockers and sailors – had an inconsistent relationship with the Labour party.”

The importance of skilled workers and Nonconformists

One reason for Labour’s earlier breakthrough in Glasgow was its stronger concentration of skilled trades. Although like Liverpool, a major port, Glasgow relied less on distribution and more on the dominant industry of shipbuilding. This provided a stronger industrial base with many skilled jobs defended by well-organised trade unions. Even if we include the Cammel Laird shipyards in nearby Birkenhead, Liverpool never had a similar level of manufacturing jobs. There was far too much reliance on low-skilled, casual labour which was a lower priority for the wider trade union movement.

At this time, areas that voted Labour had either strong trade unions, or high levels of Nonconformist Protestants such as Baptists, Methodists, Quakers – or both. You can see this trend in places like South Wales, West Yorkshire, East Lancashire, and the Durham coalfield. Nonconformity was linked with moral and political liberalism: Nonconformists such as William Wilberforce had been prominent anti-slavery advocates, and were over-represented among critics of British imperialism. They also challenged elements of the British establishment such as the Church of England and the House of Lords. In Liverpool, however, the trade unions were small or weak, whilst most people were Catholics or Anglicans, with few Protestant Nonconformists.

It is perhaps forgotten today, but back in the interwar years, the largest unions on Merseyside, the TGWU and the National Union of Seamen - representing dockers and sailors – had an inconsistent relationship with the Labour party. In 1927, the Executive Committee of the Liverpool Labour Party (then known as the Liverpool Trades Council and Labour Party) was formed from clerks, postal workers, electricians, engineers, railwaymen, painters and insurance workers. Dressmakers, shop assistants, clerical workers, tailors and garment workers were all well represented in the membership – but representatives from the two dominant occupations in the city were conspicuous by their absence.

Tories still strong after World War 2 and the politics of normal

Even after the 1945 Labour landslide, the Conservatives continued to win elections in Liverpool. Tory MPs were elected for Walton and West Derby until 1964, and for Wavertree and Garston until 1983. At the 1959 local elections, six of Liverpool’s nine council wards were controlled by the Conservatives, and three of those were solidly working-class areas, including Toxteth and Walton.

During the 1970s, control of the council swung between the Tories and Liberals. When the Trotskyist Militant Tendency took over in 1983, they succeeded a Conservative-Liberal coalition.

When Labour was successful on Merseyside in this period it was not because of a strong local labour movement, but because political sentiment was tracking with the ‘normal’, with the city tending to vote in line with national trends

Speaking to political scientist David Jeffery, who studies electoral politics in Liverpool, he told me that after the Second World War there was a general trend towards the ‘nationalisation of politics’. By this he means that national rather than local issues became key determinants in deciding how to vote. Local politics began to matter a lot less, so the Liverpool vote tracked the national vote share. As elsewhere in the country, the party in power nationally would usually suffer in local elections.

As Jeffery explained, the Tory successes in council elections during the late 1960s were not driven by a surge in support for the Tories, but rather a collapse in the Labour vote due to the growing unpopularity of Harold Wilson’s Labour government in Westminster.

Then in the early 1970s, when Ted Heath’s Conservative government was unpopular, Labour and the Liberals did better in local elections, and in 1998, a year after Tony Blair’s Labour landslide, the Liberal Democrats once again took power of Liverpool City Council.

Prone to takeover – the problem with Labour’s low local membership

Even though there was a real change of the political culture and identity of the city in the 1980s, there was still not much of a labour ‘movement’. One of the reasons Militant was able to take over Liverpool Labour was because the local Labour party branches had relatively few members. They’d become hollowed out and simply didn’t have enough people to buttress against a well-organised and well-motivated sect.

Historically, in areas without strong trade unions there would be relatively few people in the local Labour party – put simply if you were not a union member or close to a union member you were far less likely to get involved with Labour. So once the unions lost their strength and influence from the 1980s onwards, alongside a decline in local government, the traditional working class routes into local politics dried up. Membership of Labour constituency branches (CLPs) in traditional working class areas has been on the slide ever since. As an example, the biggest constituency Labour parties today such as Hornsey and Wood Green in London have over 3,000 members, but one of Liverpool’s largest, Liverpool Walton, claims to have just over one thousand, and that might have been at the height of the Jeremy Corbyn membership surge.

One of the reasons Militant was able to take over Liverpool Labour was because the local Labour party branches had relatively few members. They’d become hollowed out and simply didn’t have enough people to buttress against a well-organised and well-motivated sect.

Just as in the early twentieth century, Liverpool today has a large working-class population, but it doesn’t have much of a labour movement – despite Labour consistently winning elections.

There have been well-supported social justice movements: such as during the dock strike of 1995-1998, the Hillsborough Justice Campaign, and more recently grassroots initiatives such as Fans Supporting Foodbanks. But this hasn’t translated into high membership or engagement with the Labour party itself.

Middle-class activists and the politics of identity

Labour’s membership surged under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn from just 198,000 in 2015 to 564,000 by 2017. But how many of these new members were from traditionally working class communities? Creative Commons C.C.0 1.0 via Wikimedia.

As far back as Tony Blair, commentators have noted how the ‘Islington set’ have become increasingly influential in the politics of the Labour party. People whose personal circumstances had taken them a long way from the traditional Labour voter were now shaping the party’s direction. During Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership in the 2010s, membership of the party grew, but often those new members were not from the traditional voter base. London, by comparison to Liverpool, has far higher levels of middle-class graduates and these are exactly the kind of people who have historically joined political parties. It’s not surprising that in places with more middle class voters, there’s been increased enthusiasm and engagement with Labour. But back in the Labour heartlands, not so much. This relative lack of enthusiasm and political engagement can be seen by comparing the turnouts of the last mayoral races in Liverpool and London: in both cases, everyone knew that the Labour candidate would win, yet in London the turnout was 40%, in Liverpool it barely reached 30%.

In recent years, the Liverpool Left has become more radical on cultural issues such as race and ethnicity - but it’s doubtful whether the city’s population is as liberal as their representatives on these issues.

The website, Electoral Calculus breaks down the demographics and political culture of each of the UK’s 650 constituencies, and ranks them according to their political opinion on economics (Left versus Right), internationalism (Global versus National) and culture (Liberal versus Conservative). It then uses cluster analysis to identify the influence of one of seven ‘Tribes’ in each constituency - including ‘Progressives’, ‘Traditionalists’, ‘Centrists’, ‘Kind Young Capitalists’, ‘Somewheres’, ‘Strong Left’ and ‘Strong Right’. It also estimates how each constituency seat voted in the Brexit referendum, a much finer grain of breakdown than exists in the official statistics.

Let’s take a look at how it assesses Liverpool’s five safest Labour seats:

Liverpool Walton - Traditionalist

27 degrees Left, 3 degrees Globalist and 1 degree Conservative; 52% voted Leave.

Knowsley - Traditionalist

26 degrees Left, 2 degrees Globalist, 2 degrees Conservative; 52% voted Leave.

Bootle - Traditionalist

25 degrees Left, 3 degrees Globalist, 0 degrees Social; 50% voted Leave.

West Derby - Traditionalist

26 degrees Left , 6 degrees Global, 1 degree Liberal; 48% voted Leave.

Liverpool Riverside – Strong Left

21 degrees Left, 29 degrees Globalist and 18 degrees Liberal; 27% voted Leave.

As you can see, the top four constituencies are classed as ‘Traditionalists’, according to the Electoral Calculus formula. The people in these seats have, on average, left-wing economic views but cultural and social views that are centrist or conservative.

Traditionalist Kirkby. Small ‘c’ conservatism may rule when it comes to social and cultural views in many of the region’s Labour constituencies. Image Kirkby High Street (2023) by Paul Bryan

In a recent study into how local identities impact on voting behaviour in the Liverpool City Region, David Jeffery also found that while Liverpool constituencies are in the bottom quarter nationally in terms of pro-monarchy sentiment, they are still more pro than anti-monarchy. He found that only 18% of Liverpudlians feel ‘only Scouse’, just 5 percentage points higher than the 13% who feel ‘only English’, with the rest feeling some mixture of Scouse and English.

What can we read into this?

It appears that despite the victories of the Labour party in parliamentary and local elections, there is a large amount of small ‘c’ socially conservative sentiment in the city. That is why up to three constituencies likely voted Leave, and why UKIP came third in the 2014 local elections – only 969 votes off the Greens in second place. They did especially well in working-class wards such as Club Moor, County, Fazakerley, and Norris Green.

This data suggests there’s a risk of Liverpool Labour overreaching on culture, as happened recently with the Scottish National Party (SNP). Despite Scotland’s population being slightly more sceptical on trans rights than the UK average, the SNP leadership assumed they could push forward with radical gender policies - an approach which led to Kate Forbes, who opposes same-sex marriage, coming within 3,000 votes of winning the party’s leadership election.

Within the past year, the SNP has gone from looking invulnerable to now polling only 1% ahead of Labour. Obviously this has not all been down to overplaying their hand on cultural issues, but nonetheless it’s a salutary warning for Liverpool Labour about the dangers of hubris, and mistaking the transformation in the politics of the city for a transformation in its culture.

In the hundred years since the election of the city’s first Labour MP, Liverpool’s support for Labour appears stronger than ever. But history suggests an unpopular Starmer government and continued chaos at the municipal level could well see the party lose power locally and for the majorities of the city’s MPs to be chipped away. The city’s current loyalty to Labour cannot be taken for granted, either by national politicians looking to Liverpool for lessons, or by local figures who might mistake voting patterns for political and cultural radicalism.

David Swift is a historian and writer specialising in Left wing activism who has written for publications such as the New Statesman, The Times, Tribune and Unherd. He is the author of three books including A Left For Itself; and The Identity Myth.

His latest book, Scouse Republic? A Personal History of Liverpool, will be published in 2024 by the Little, Brown Book Group.

*Main image created on Stable Diffusion.

Mancpool: One Mayor, One Authority, One Vision?

Should the city of Liverpool throw in its lot with Manchester and accept one combined North West Metro Mayor to rule us all? Despite admitting that such a suggestion is about as saleable as a One State Solution for Israel-Palestine, Jon Egan thinks it’s an idea whose time has come. It’s certainly an idea that’s provoked some debate within Liverpolitan Towers. But what do you think?

Jon Egan

Manchester Bees Meet Liverpool Super Lambananas by mmcd studio

Is it time the city of Liverpool threw its lot in with Manchester and accepted one combined North West Metro Mayor to rule us all? Jon Egan thinks so. As you can imagine, the suggestion has caused some debate in Liverpolitan Towers and we are not all in agreement. But what do you think? Here Jon makes his case and hints at future initiatives to come…

So let me issue a warning now. This article contains material that many Liverpudlians will find deeply distressing and offensive. It’s an argument that I have tentatively proffered in the past, but after profound and serious reflection, have concluded, now needs to be set out in the most explicit and uncompromising of terms. You have been warned.

David Lloyd’s recent article for The Post lamenting the exodus of Liverpool’s “best and brightest” was as ever an enlightening and enjoyable read, notwithstanding its downbeat and dispiriting narrative of civic and economic decline. If I can add a generational postscript in support of David’s thesis, every member of our youngest daughter’s friendship group from Bluecoat School now lives and works outside Liverpool.

It was the nineteenth century philosopher, Friedrich Nietzche who argued that only as an “aesthetic phenomenon” does the tragedy of human existence find its eternal justification, and perhaps it’s only in the exquisite prose and imaginative virtuosity of David’s writing that Liverpool’s own tragic predicament becomes philosophically palatable. I admire David’s resolute determination to find some tiny component of hope, offered in the city’s joyously ephemeral hosting of Eurovision 2023. But does our capacity for celebration, hospitality and togetherness provide the alchemy for a viable economic renaissance? Does it, at best, illuminate Liverpool’s status as a half-city, stripped of its economic and productive assets, now reduced to the sheer potentiality of its human capital?

The idea of Liverpool as a stage set for cultural spectacles and entertainment extravaganzas (hyperbolically described by the city’s cultural supremo, Claire McColgan as “moments of absolute global significance”), is a beguiling substitute for an actual economy, and an ability to offer a livelihood for the generations who continue to depart for more attractive and seemingly successful cities. It’s a vision that also reminds me of another of Italo Calvino’s magical realist parables in his masterpiece novel, Invisible Cities. Sophronia, the half-city of roller-coasters, carousels, Ferris wheels and big tops, where it is the banks, factories, ministries and docks that are dismantled, loaded onto trailers and taken away to their next travelling destination.

“I fully grasp the deeply heretical nature of this proposition. A ‘One State’ solution for the Liverpool and Manchester City Regions is about as saleable as a one state solution for Israel and Palestine.”

Two hundred years ago, the realisation that we were a half-city inspired Liverpool’s city fathers to contemplate a project that would have world-changing implications - a genuine moment of “absolute global significance”. Prior to the construction of the world’s first inter-city railway, every human journey between major population centres would be dependent on the locomotive capabilities of the horse. Railways were the harbingers of modernity, compressing time and space, and in this instance, connecting one of the world’s great trading centres with its greatest manufacturing hub. Umbilically conjoined, the two half-cities (the place that trades and the place that makes), became the nexus for Britain’s industrial and imperial prowess for the next hundred years.

If the railway brought Liverpool and Manchester closer together, recent decades have been dominated by a football-terrace inspired antagonism aimed at driving us further apart. Liverpool’s antipathy to our more affluent neighbour would seem also to betray more than a slight hint of jealousy, as our rival has greedily accumulated the trappings and status of regional capital.

Rather than resenting Manchester’s success or investing in a strategy of do-or-die competition, is there a smarter and mutually beneficial alternative? Is it time to re-imagine a more symbiotic relationship, that realises that for every British provincial city, the real competition is located 200 miles to the south?

Of course, this is not an original proposition. In the early noughties, Liverpool Leader, Mike Storey and his Manchester counterpart, Richard Leese signed their much lauded Joint Concordat - an agreement only marginally less shocking than the Molotov-Ribbentrop ‘Non-Aggression’ Pact of 1939 between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The benefits were equally short lived. The agreement was conceived in the golden age of regionalism when under the aegis of John Prescott’s mega-ministry - the Department for the Environment, Transport and the Regions - levelling-up and rebalancing were not mere meaningless mantras but core political imperatives. For all its good works, the now defunct North West Development Agency, which once employed 500 people to drive the region’s growth, was more of a hindrance than an enabler for a serious rapprochement between the city’s two main economic players. Determined to uphold scrupulous neutrality between Liverpool and Manchester (it’s Warrington-base memorably described by broadcaster and musical impresario Tony Wilson as being located in the “perineum” of the North West), the agency was forged by a powerful Labour Lancashire mafia, with a brief to prevent and constrain the domineering tendencies of the two cities.

The ill-fated 2001 Joint Concordat between Liverpool and Manchester was only marginally more palatable than the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 which saw the carve up of Poland. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H27337 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

“The idea of Liverpool as a stage set for cultural spectacles and entertainment extravaganzas is a beguiling substitute for an actual economy.”

The Storey-Leese pact conceded Manchester’s status as regional capital, a painful admission of subservience that probably explains the reluctance of subsequent Liverpool leaders to pursue similar overtures. The Liverpool City Region and Greater Manchester devolution deals, and the election of “great mates” Steve Rotheram and Andy Burnham has seen little practical collaboration, beyond occasional media stunts and chummy get-togethers to compare their favourite home-grown pop tunes. Those who expected more than a Northern Variety Hall double act have thus far been disappointed by devolution projects intent on protecting sub-regional domains and denying the compelling reality of geographic and economic interdependence.

We’re two cities less than 30 miles apart, whose fuzzy edges and increasingly footloose populations are blind to civic boundaries that no longer delineate where or how people live, work and play. People are already beginning to see and experience the cities as a single urban place - we just need to dismantle some of the physical and administrative obstacles.

It is beyond farcical that train travel between the two city centres is only marginally quicker today than it was when Stephenson’s Rocket completed its maiden journey two centuries ago. At a pre-MIPIM real estate seminar a few years ago, a Liverpool property professional opined that the single biggest boost to Liverpool’s commercial office market would be a 20 minute train service to Manchester city centre. Who knows, it may even have been enough to persuade Liverpool-nurtured companies like the sports fashion-brand, Castore, to stay in a better connected city location instead of moving to our city neighbour (and taking 300 jobs with it). Questioning the benefits of a fully integrated single strategic transport authority to straddle the two city-regions, is equivalent to advocating the abolition of Transport for London and its replacement by two rival authorities with briefs never to talk to each other.

“Rather than resenting Manchester’s success or investing in a strategy of do-or-die competition, is there a smarter and mutually beneficial alternative?”

For those who ask what’s in it for Manchester, the answer is the well attested and quantifiable benefits of economic agglomeration - cost efficiencies, labour pooling, expanded markets, knowledge spill-overs… Whilst working for the think tank, ResPublica on a project to build the economic case for Liverpool’s connection to HS2, I was staggered to hear Manchester’s economic strategist Mike Emmerich admit that his city envied aspects of Liverpool’s asset-base. The hard and soft criteria by which urban theorists like Saskia Sassen measure the credentials of aspiring global cities, seem evenly dispersed between the twin cities of the Mersey Valley. We can’t match Manchester’s international transport connections, its media and knowledge clusters, but neither can they compete with Liverpool’s global brand, our cultural prowess, architectural grandeur and liveability offer.

If transport is the no-brainer, the wider benefits of agglomeration need to be systematically mapped and identified. The amorphous promise of a Northern Powerhouse can only be realised in physical space, and the contiguity of our two city regions make this the most viable location for a re-balancing project. If the North is ever to grow an economic counter-weight to London, then connecting the two closest jigsaw pieces together seems like a sensible undertaking. Whether its land-use planning or plotting economic development, investment and skills strategies, it’s nonsensical for the two city regions to be pursuing their respective goals in blissful oblivion of what is happening on the other side of an arbitrarily contrived line on a map.

Notwithstanding, its invaluable enabling role in gap funding development and infrastructure projects, the North West Development Agency was a political creation without underpinning logic or legitimacy. Were there ever any connecting threads of economic interest between Salford and Penrith? Wilmslow and Barrow-in-Furness? The Agency’s opaque governance, and its tortuous high-wire balancing act, placating a multiplicity of sub-regional agendas and interest groups, inhibited its ability to optimise the potential of the region’s two great economic engines.

So here comes the controversial bit. Pacts, concordats and convivial personal relationships are simply not sufficient to realise the potential of a new economic relationship between the two city regions - one that acknowledges that their respective asset-bases can be curated for mutual benefit. The only solution is a new governance structure - a devolution model with one Metro Mayor and one Combined Authority. I fully grasp the deeply heretical nature of this proposition, and the threat that it seems to pose to the identity and autonomy of a city that suspects it will be the junior player in any such arrangement. But are identities any more compromised in a ‘Twin City Region’ than they are within the current dispensation? St Helens, Sefton, Wirral, Wigan, Bolton amongst others would probably argue not. The integrity and jurisdiction of the respective city councils and other local authorities would not be compromised - we would only be pooling functions and responsibilities that are already acknowledged to be regional, and projecting them onto a bigger and less artificially contrived regional canvas.

“The only solution is a new governance structure - a devolution model with one Metro Mayor and one Combined Authority.”

Once upon a time, Liverpool and Manchester were authorities under the even more commodious administrative umbrella of Lancashire County Council, and as I‘ve mentioned, more recently, through the North West Development Agency, we were content to buy into the concept of a North West regional project conspicuously lacking any democratic accountability.

In a Twitter / X exchange with Liverpolitan a few weeks ago, I was asked to defend this joint governance proposition by pointing to a successful or established similar model elsewhere in the world. In the US, the twin cities of Minneapolis and St Paul, and of Dallas and Fort Worth, and the urban centres of the San Francisco Bay Area have come together in different ways to pool planning, transportation and economic development responsibilities. Closer to home, the Ruhr Regional Association in Germany exercises both a statutory and enabling role in areas including planning, infrastructure, economic development and environmental protection for the cities of Dortmund, Duisburg, Essen and Bochum. But even if there is no precise template elsewhere, should this be an inhibitor to the cities that built the world’s first inter-city railway, and that pioneered many of the most progressive advances in civic governance in the 19th and early 20th centuries?

In the absence of compelling practical arguments against the proposition, the most likely and persuasive objection will be that the mutual rivalry runs too deep, the antagonism is simply too intense and has festered too long. A ‘One State’ solution for the Liverpool and Manchester City Regions is about as saleable as a one state solution for Israel and Palestine. Maybe it’s an argument that requires a solution or a process rather than a rebuttal. In truth, antipathy is a quite recent addition to a history of rivalry that owes more than a little to the intensity of the competition between the country’s two most successful football teams. Exorcism perhaps requires a practical project, an enthusing collaboration that focuses on shared cultural attributes and ambitions. Somewhere not far away such an idea is maturing, but I will leave it to its progenitors to expand, perhaps on this platform, and maybe very soon.

Of course, there is another motive and spur for this idea which relates to the abject failure of governance within the city of Liverpool and the continuing inability of its dysfunctional political class to nurture or curate those incipient possibilities that so rarely reach fulfilment. The uprooting of Castore from Liverpool to Manchester is an instructive case study, but so too are the games companies, the biotech businesses, legal and insurance firms that have hatched in Liverpool and gone on to prosper elsewhere. Maybe we need governance less rooted in parochial politics and less constrained by cultural legacy. To borrow an analogy from Iain McGilchrist’s Divided Brain hypothesis, perhaps Manchester’s busy-bee utilitarianism and non-conformist pragmatism is the left hemisphere counterpoint to Liverpool’s wistful dreaminess (even our civic emblem is an imaginary being). Is it just possible that our divergent dispositions and outlooks are not actually a prescription for unending antagonism but the formula for a fruitful alchemy?

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Pact! What Pact? An Insider’s View on the Lost Battle to Defeat Labour

In the run-up to the 2023 Local Elections in Liverpool, three men working in the shadows, tried to corral the opposition parties into a pact capable of doing some serious damage to Labour at the polls. But in the face of factional intransigence, personality clashes and party ambitions it was doomed to failure. This is the inside story of that failed mission told by one of those men.

Jon Egan

In the run-up to the 2023 Local Elections in Liverpool, three men working in the shadows, tried to corral the opposition parties into a pact capable of doing some serious damage to Labour at the polls. Described as an exercise in herding cats, the enterprise was ultimately doomed to failure, as factional intransigience, personality clashes and party ambitions took hold, before the electorate then delivered the killing blow. This is the inside story of that failed mission told by one of those men, political consultant, Jon Egan.

“Why are we doing this?” is a question that former BBC Radio Merseyside broadcaster, Liam Fogarty and I have been asking ourselves on and off for more than twenty years.

Even before our involvement in the now largely forgotten Liverpool Democracy Commission, we have been kept up at night wondering how to fix Liverpool's broken civic democracy. Years pumped into a losing battle, the odds very much against us. Have we been wasting our time?

The context for the latest phase of anguished introspection was this year’s local elections in Liverpool which, as you may have noticed, returned Labour to power with an increased majority on the City Council. Before explaining the efforts that Liam, myself and Stephen Yip, a former City Mayor candidate and founder of the charity, KIND, made to avert this seemingly predestined eventuality, it’s worth taking the time to fully comprehend and meditate upon the extraordinary fact of Labour’s victory.

There is no simple or rational explanation for Labour’s achievement, although the campaigning skills of my former Labour Party colleague and strategist, Sheila Murphy need to be duly recognised. The Labour campaign was a brilliantly executed masterclass in misdirection, diversion and manipulation worthy of the illusionist, Derren Brown - wiping the collective memory of the city’s voters and convincing them that their party bore absolutely no responsibility for the endemic chaos, waste, corruption and ineptitude of the last ten years. This election, apparently, had little to do with how a struggling city, effectively governed by colonial administrators, was going to put its house in order. No, it turns out the script was the old familiar one about sending a message to the city's historic arch-nemesis - The Tories.

The result, I suppose, proves precisely how difficult it is for people to overcome addictive and self-harmful habits like voting Labour in Liverpool. Maybe what the city needs is not so much new councillors, but counselling.

‘The Labour campaign was a brilliantly executed masterclass in misdirection, diversion and manipulation worthy of the illusionist, Derren Brown.’

In The Myth of Sisyphus, the writer Albert Camus defined the absurd as the irreconcilable gulf that separates human aspirations from the world’s predisposition to thwart them. The tragic image of Sisyphus struggling to roll his enormous boulder to the top of the hill, already sensing the futility of his labours against the forces of gravity, is an apt metaphor for the investment in time that Liam and myself have made in initiatives, campaigns and conversations undertaken over many years in the hope of making Liverpool’s politics function normally. So if the narrative of this election campaign carries the darkly comic resonances of dramatists, Beckett and Ionesco, and their Theatre of the Absurd, then this is not literary pastiche, but rather the perfect paradigm for Liverpool politics. And in that spirit, it seems appropriate to start not at the beginning, but at the end.

One of the most inexplicable aspects of the election result, was the way that the defeated parties far from despairing at the loss of an historic opportunity, were to varying degrees seemingly satisfied (or at worst only mildly disappointed) with their less than modest achievements. For the Liverpool Community Independents getting only three of their cohort re-elected was at least ‘a springboard’ from which to progress. For Green Party Leader, Tom Crone, “bitter disappointment” extended only as far as lamenting the loss of one target ward (Festival Gardens) by a single vote.

For Richard Kemp, the eminence grise of Liverpool Liberal Democracy, the pitiful addition of three councillors, would give his party “plenty of time for reflection on how the council should work, and where the city should be going.” One wonders how after four decades as a City Councillor, Richard was still trying to figure out these rather elementary conundrums, before he finally decided to fall on his sword and announce his long anticipated retirement as party leader.

So let’s rewind to the beginning, or at least the beginning of Act 2. Act 1 being the heroic, but ultimately doomed campaign by Stephen Yip, to be elected as City Mayor in 2021.

Running a surprisingly close and creditable second to Labour’s Joanne Anderson , Yip’s undoing was the stubborn refusal of Green Party Leader, Tom Crone and the ubiquitous Kemp to stand aside to allow for the possibility of deliverance from a disgraced and discredited Labour administration. The 2021 election seemed, at the time, to be a decisive “never again” moment, with penitential expressions of regret from Liberal Democrats and Greens and pledges to learn the lesson of fractured opposition.

Like trying to roll a rock up a hill. Now more than ever, Liverpool’s opposition parties needed to master the alien vernacular of co-operation.

So to Act 2

Following the publication of the Caller Report in 2021 it was decreed that Liverpool should abandon the baroque and inscrutable election-by-thirds system, and instead adopt an all-out election on new boundaries with the majority of councillors to be elected from single member wards. Now more than ever, Liverpool’s opposition parties needed to master the alien vernacular of co-operation. Seemingly unable to conduct conversations between themselves, the task of scoping the opportunities for an electoral pact fell to myself, Stephen Yip and Liam Fogarty. Having manoeuvred the boulder to within inches (well maybe a couple of hundred metres) of the summit in 2021, we felt that one more effort was something we owed both to ourselves and the people of Liverpool. Far from delivering the new dispensation promised following her election, the era of Anderson 2.0 (Joanne) was notable mainly for its dismal continuity - a botched energy contract costing the city millions, hundreds of millions more written off in uncollected tax and rates, revelations concerning councillors dodging parking fines and extended roles for Government Commissioners taking responsibility for even more substandard and failing services.

The process of encouraging political and electoral co-operation between Liverpool’s opposition factions began with a discrete gathering at Richard Kemp’s house in the summer of last year. Treated to copious quantities of sausages and dips, a generally constructive exchange with Richard and his Lib Dem colleague, Kris Brown, concluded with a suggestion that Liam attend their upcoming policy conference to raise a few issues and provide an outsider perspective on the challenges of the upcoming election. Both from this gathering and the subsequent conference, we sensed a distinct lack of enthusiasm for the idea of any form of electoral pact. If this was to happen, pressure rather than polite persuasion might need to be applied.

By the end of the year, we had started informal conversations with friends and contacts within the other three opposition groups - The Liberal Party (an eccentric relic from the pre-Alliance / Lib Dem era sustained in Liverpool through the hyperactive exertions of its charismatic talisman, Cllr Steve Radford), the Liverpool Community Independents (a party formed by dissenting former Labour councillors primarily disillusioned by cuts and corruption) and the Green Party. With the prospect of another squandered opportunity on the horizon, we resolved to take the decisive step of inviting the leaders to a more formal gathering hosted by Stephen Yip at the HQ of his charity, KIND. The tactical approach was to corral the three most willing participants into an agreement and then publicly challenge or shame the Liberal Democrats to come on board.

‘It began with a discrete gathering at Richard Kemp’s house in the summer of last year, where we were treated to copious quantities of sausages and dips.’

Eschewing sausages for club biscuits (salted caramel flavour), the more business-like ambience of the gathering cut straight to the quick. Without an agreement from opposition parties (all of whom occupied terrain to the left of the centre) we would be facing the prospect of another four years of Labour misrule. Apart from pointing out the mutual benefits of a pact, we offered to provide whatever practical, organisational and campaigning resources we could muster from the networks created during Stephen Yip’s mayoral campaign. Admittedly, these were no match for the Labour legions, but we believed they could help the disparate groups to sharpen core messages, target more efficiently and raise the quality and potency of communication collateral. These resources were conditional on the reality of a pact and a clear indication that its participants were putting city before party.

From the outset the Liberals and Community Independents were fully and unequivocally committed to the principle and practicalities of a pact. For Tom Crone and the Green Party, the proposition was clearly more problematic. Promising to take the idea away for "consideration", we were left with an uneasy sense that history was repeating itself. It was unclear at the time, and indeed still is, by what means of mysterious convocation, the Liverpool Green Party reaches its decisions. With Tom intimating that the national party was instructing them to field the maximum possible number of candidates, the sad implication was that regime change in Liverpool was less of a priority than adhering to the diktat from on high. After several days of radio silence, I was tipped off that Tom would be attending a film event at St Michael's church, and it might be a useful opportunity to see how things were progressing. Our conversation, sadly, revealed that they weren't, and that even a three party pact was becoming an unlikely, if not entirely illusory, possibility.

Stephen Yip's description of our undertaking as an exercise in herding cats was suddenly complicated by the unexpected arrival of a much more exotic species defying all known zoological and political categorisations. The first in a series of audiences with hotelier and property developer, Lawrence Kenwright, took place in late December in the sepulchral gloom of the Alma de Cuba bar, formerly St Peter's church. The bar had been the venue for a series of revivalist-style rallies at which Kenwright had railed against council corruption, presenting himself as the figure-head for a new, popular movement called Liberate Liverpool, that would sweep aside the cliques and cabals that had brought the city to its current parlous state.

‘It was unclear at the time, and indeed still is, by what means of mysterious convocation, the Liverpool Green Party reaches its decisions.’

I was deputed to conduct the initial conversation, that provided a fascinating insight into Kenwright's character and motivation, the history of his relationship with the City Council and Mayor Joe Anderson, and the ambitions underpinning his political project. Kenwright's almost visceral determination to unseat Labour was evident; what was less clear was his precise role in the project, and the means and method by which it was to be achieved.

Whilst it was easy to understand the motivations behind Liberate Liverpool, and its attraction as an antidote to an out of touch and self-serving politics, it was difficult to believe that it offered any kind of remedy. Symptoms are not cures, and Liberate Liverpool’s attraction for cranks, conspiracists and far-right interlopers was perhaps an inevitable consequence of its febrile genesis and almost millenarian rhetoric. Some good and sincere people answered the call only to be sent into battle with the campaigning equivalent of peashooters and water pistols. At a subsequent meeting (accompanied this time by Liam Fogarty and ex-Labour Councillor Maria Toolan), we embarked on what we thought was a subtle policy of dissuasion, politely pointing out the inherent flaws of a campaign targeting "people who don't vote" and relying almost exclusively on social media, only to be accused by a Kenwright acolyte of "disrespecting Lawrence."

Our approaches were an attempt to scope the albeit remote possibility of identifying suitably vetted independent candidates who could be assumed into a broader-based Clean-Up Coalition. It is an indicator of our desperation that this hope was ever entertained.

‘We embarked on a subtle policy of dissuasion, politely pointing out the inherent flaws of a campaign targeting "people who don't vote" only to be accused by a Kenwright acolyte of "disrespecting Lawrence."'

As February rolled into March, our efforts became simultaneously more modest and more desperate. Following advice from a sympathetic insider, we were advised to bypass Kemp and re-pitch the idea of an electoral pact to the Lib Dems through the party's former leader and campaign supremo, Lord Mike Storey, who we later discovered was to stand as a candidate in Childwall. Alas Stephen Yip’s conversation with Storey was even more emphatically negative than the sausage-gate soiree with Kemp months earlier.

It was clear we needed to explore more pragmatic alternatives. If not a city-wide pact, perhaps a nod and a wink understanding to avoid actively campaigning in each other's target seats? Maybe also an agreement around some core commitments to improve transparency and accountability, combat corruption and restore public confidence in the City Council? Initially, Richard Kemp sounded refreshingly and surprisingly up for it, but with the fatal complication that some of their target seats were also target seats for the Greens and the Liberals. Nods and winks would have to be restricted to the safest Labour seats in Liverpool where none of the opposition parties entertained serious hopes of winning. In other words, for show only. Meanwhile, Stephen Yip drafted four pledges on transparency and corruption, which were immediately endorsed by the Community Independents and the Liberal Party. The Lib Dems, however, would not sign up; the response published on the But What Does Richard Kemp Think? blog, a depressingly patronising and public epistle "explaining" that the proposals were either illegal, already in place (due largely to his efforts) or would be a waste of money. It seemed futile to point out to Kemp that the proposal for an Independently-chaired Standards Board was not only perfectly lawful, but had been initially drafted for Stephen's Yip’s 2021 manifesto by Howard Winik, who was now a Liberal Democrat candidate.

Unlike his predecessor, does the Lib Dem’s new leader, Carl Cashman have the imagination or inclination to detach his party from its comfortable civic niche in South Liverpool suburbia?

For me, this was perhaps the final and conclusive evidence that laid bare the true nature of Liverpool Liberal Democrats and their deep complicity in a council whose corrupting and dysfunctional culture long predates the shortcomings of the Joe Anderson era. They are not, in my view, an "Opposition Party" in any meaningful sense of the word, but are more akin to the tame collaborators in the sham democracies of the Soviet Bloc - the Liverpool equivalent of the Democratic Farmers Party of East Germany. They have no desire to fundamentally reform or reset a moribund civic culture, but are content to bide their time in the hope that circumstances will grant them an opportunity to preside over its decrepit edifice. In one sense, Liberate Liverpool were right; the Liberal Democrats are not part of a solution, but are an intrinsic and intractable part of the problem. Whether Kemp’s much younger successor, the neophyte Carl Cashman, has the imagination or inclination to detach his party from its comfortable civic niche and the bucolic pastures of South Liverpool suburbia, will largely determine whether Liverpool's local democracy remains a hollow charade, or becomes an empowering mechanism for change.

‘The Lib Dems are not an "Opposition Party" in any meaningful sense of the word, but are more akin to the tame collaborators in the sham democracies of the Soviet Bloc - the Liverpool equivalent of the Democratic Farmers Party of East Germany.’

Epilogue

It is the tragic-comic circularity of the narrative that makes Liverpool politics an absurdist drama. The interminable wait for Godot - an intervention, a new structure, a new political alignment, a salvific figure able to break the cycle of failure, corruption and chaos that has blighted our city for as long as anyone can remember.

On the day of polling, I was helping Maria Toolan with some last minute door knocking to encourage supporters to get out and vote in the City Centre North ward. She was already sensing with fatalist resignation, that her efforts to unseat two former Labour colleagues had failed. "The problem is," she lamented "people aren't bothered about waste and corruption, it's what they expect from the city council and they don't believe that it's ever going to change."

This is the suffocating dead weight of Liverpool politics, an oppressive inertia and sense of fatalism engendered by decades of broken promises, betrayed trust and shameful failure. It's the gravitational drag that immobilises progress and snuffs out any glimmer of a more honest and hopeful politics.

Labour's strategy understands and exploits this endemic cynicism. It doesn't really matter how badly we've governed Liverpool, this is a Labour city and elections cannot alter this brute existential reality. Sending a message to the Tories might actually seem like a more worthwhile place to put an ‘X’ than investing in a hope for something better, when you suspect that this isn't even a logical possibility. Little wonder that 8 out of 10 Liverpool voters decided to stay at home.

Would an electoral pact have unseated Labour? Would it have signalled to voters that there was a tangible possibility of an alternative administration? It's hard to say, but looking at the results and totting up the number of seats where competing opposition parties on the progressive wing of politics won more votes than the Labour majority, it cannot be completely discounted.

Labour mis-fire. By personalising the campaign against Gorst, they had also localised it. In Garston, the election was no longer a rehearsal for a General Election. It was about the honesty and integrity of individuals and their credentials to represent their community - weak territory for Labour to fight on. Photo from Twitter @Pablo8485

If there is cause for hope, it was in the response to what was one of the most deplorable manifestations of Liverpool Labour's darker instincts. The officially sanctioned Labour campaign, scripted from on-high and professionally disseminated under the supervision of Sheila Murphy and their Regional Office, was a vacuous mash-up of kick-the-Tories and Eurovision-phoria. But beneath the sanitised veneer another more vicious and toxic campaign was being waged against Community Independent candidates who had originally been elected under Labour colours. Fake social media accounts became platforms to abuse, ridicule and defame the Community Independents with particular venom aimed at Sam Gorst, a former Labour Councillor seeking re-election in Garston.

The ferocity of the campaign against Gorst reached its nadir with a shamefully deceptive leaflet masquerading as a community newsletter which raked up Gorst's old social media posts, and more seriously, falsely implied that he had used his position as a councillor to jump the social housing queue. Within an hour of the leaflet being issued, we launched our final, and perhaps only effective contribution to the election campaign. A round-robin email was despatched to secure the support of the city's four opposition leaders in a joint denunciation of Labour's malicious and dishonest leaflet. And to their credit, Kemp, Radford, Crone and the Community Independent's Leader, Alan Gibbons all replied with personalised quotes for a media release within 30 minutes. The unprecedented show of unity secured positive media coverage, that was followed by The Echo's political correspondent, Liam Thorp exposing the tell-tale fingerprints of Labour on the scurrilous social media accounts.

An otherwise faultless Labour campaign had slipped up. By personalising the campaign against Gorst and his running mate Lucy Williams, they had also localised it. This election and the campaign against Alan Gibbons in Orrell Park, were no longer just dummy run rehearsals for a General Election or a vote of thanks for delivering Eurovision; they were about the honesty and integrity of individuals and their credentials to represent their community. Gorst, Williams and Gibbons' victories may or may not be a platform for the future growth of the Liverpool Community Independents Party, but they are perhaps a hopeful intimation that gravity doesn't always win.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Can Liverpool be Liberated from Labour?

From black ops-style campaigns to discredit rival independent candidates by the local Labour Party to the unlikely rise of the ultimately doomed anti-corruption movement, Liberate Liverpool, the city’s local elections proved to be one of the most fiercely contested in years. And then Labour won. Writing for UnHerd on the eve of the election, Liverpolitan Editor Paul Bryan describes the fervid atmosphere of the campaign amongst the hopes and shattered dreams of candidates of all colours.

Local Elections 2023

Paul Bryan

This article by Liverpolitan Editor, Paul Bryan was published by UnHerd on 3rd May 2023 on the eve of the 2023 Local Elections in Liverpool. To read the whole feature visit…

Before Liverpool can bask in the joy of hosting next week’s Eurovision Song Contest, it must first contend with tomorrow’s local elections — and the rounds of mudslinging that have come with it. Take one of Labour’s election pamphlets, pushed through the letterboxes of residents in the south of the city. Disguised under the banner of Garston Resident News, the leaflet mined old social media posts belonging to independent councillor, Sam Gorst, who had been expelled from the Labour Party in December 2021 for associating with Labour Against the Witchhunt, a group opposed to “the purge” of pro-Corbyn supporters for alleged antisemitism.

Under the headline “Sickening”, Gorst was criticised for historic posts in which he called Queen Elizabeth “a useless bitch” and the Jewish former Liverpool Wavertree MP Luciana Berger, who eventually resigned from the party, a “hideous traitor”. The pamphlet also claimed that he lived in a “leafy” area and insinuated that he had jumped the queue on social housing, although that accusation is contested.

But if the intention was to make an opponent look bad, Labour may have shot itself in the foot. A joint statement released by the Liberal Democrats, The Liverpool Community Independents, The Green Party and the Liberal Party described the leaflet as “cynical”, “dishonest” and “shameful”. Their calls for a clean fight, however, have fallen on deaf ears, not least because the mud is being thrown in all directions amid widely reported allegations of Labour corruption and incompetence.

“In cities with a more contested political complexion, one might expect such failures to be severely punished at the ballot box. But this is Liverpool, and ousting Labour is the toughest of political challenges.”

Snippet taken from a Labour election pamphlet disguised under the banner of Garston Resident News,

To read the whole article visit…

https://unherd.com/2023/05/can-liverpool-be-liberated-from-labour/

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Why we should stop banging on about Thatcher and the Toxteth Bloody Riots

Journalists arrive in Liverpool to tell the same story over and over again - the city cast as the lead in a Shakespearean morality play, fuelled by righteous anger, touched by tragedy, let down by treachery. Yet is our own obsession with the 1980s feeding the media stereotypes?

Paul Bryan

My personal experience of the 1981 Toxteth Riots existed, as for so many others in Liverpool, solely on television. The nightly news reports showed lines of police officers cowering under shields as youths hurled stones and set light to cars and buildings. I didn’t know why it was happening but I knew it was exciting and so did my friends – as if through some mechanism of the collective unconscious we quickly turned it into a street game, unimaginatively called ‘Toxteth Riots’. The rules were fairly simple. All you had to do was clutch a metal bin lid and defend yourself from rocks and stones hurled somewhat half-heartedly by your mates. The winner was the one who could stick it out for the longest. Writing about this now, I’ve only just realised, we were instinctively putting ourselves in the shoes of the police. They at least seemed understandable. Still, it didn’t hold our attention for long. We got bored of it after two nights.

If only I could say the same about the national media. 41 years later and they’re still using the Toxteth Riots as the go-to framing device for just about any story on Liverpool. Of course, in no way do I mean to belittle the experiences of those who were there, or those who suffered under the social forces that made life more difficult. But for me growing up, the riots always felt like something distant, from some other Liverpool, far off and largely irrelevant. If anything, the Toxteth Riots were a boon – they gave me the chance to meet TV scarecrow, Worzel Gummidge at the International Garden Festival three years later, thanks to the intervention of Michael Heseltine, unofficially crowned the Minister for Merseyside.

I mention this personal story because I’ve noticed a tendency in the media and in political circles to describe Liverpool as a single unit, with a single, monolithic outlook and I find this approach unhealthy and untrue. The Toxteth Riots as history and metaphor have become something of an unquestionable foundation stone in our understanding of Liverpool’s journey. I’m not for one minute doubting their significance, but merely wish to flag that, due to the vicarious nature in which they were experienced by many, the events will never speak to us all in the same way and I think that’s worth acknowledging given the sometimes over-simplified, stripped-down caricature of ‘Scouse’ tales that we are often encouraged to identify with. And if that applies to someone who was alive at the time, you can bet it will apply even more to those who were as yet unborn.

The Toxteth Riots sit as the starting point of a master narrative that is told and retold ad finitum. Typically, it’s a story pitched as one of strife and rebirth – a city on its knees rising phoenix-like from the ashes with the regeneration that followed. Either that or it’s used to evidence our home town’s long history of racial inequality. There are further beats in the story of course and usually they point to ‘basket-case’ – a city that just can’t seem to catch a break or get its house in order. A place that is frankly perplexing. Journalists visiting Liverpool tell the same story, time after time, yet they never tire of it, new facts on the ground serving merely to embellish an already familiar pattern.

It would be easy to point the finger at outsiders here, but this game plays out amongst Liverpool’s inhabitants too and I’ve begun to wonder… does the incessant focus on the 1980s (and we must throw the hate figure that is Margaret Thatcher into the same pot) does the constant repetition serve the city’s best interests? Do these references still yield insight or are they just a reheating of old battles, about as useful to understanding Liverpool today as the Suez crisis is to making sense of Britain’s contemporary approach to foreign policy?

A case in point. This week, the Mayor of Liverpool, Joanne Anderson was interviewed by a journalist from the left-leaning New Statesman magazine, enticed no doubt by the city’s hosting of the Labour Party Conference. Ostensibly about Liverpool’s current political crisis, the article began like this… “In 1981, the violent arrest of a young black man near Granby Street in Toxteth, Liverpool, led to nine days of rioting.”

“Journalists visiting Liverpool tell the same story, time after time, yet they never tire of it, new facts on the ground serving merely to embellish an already familiar pattern.”

What followed was a tick list from the unofficial media guide to Liverpool which we presume is handed out by the NCTJ on journalism graduation day. Margaret Thatcher, ‘managed decline’, European Capital of Culture and the regeneration of the Albert Dock, Derek “Degsy” Hatton and the Militant Tendency, gang warfare and the shootings of young children, now sadly updated with new names. Welcome to Fleet Street’s version of Punxsutawney where we’re all doomed to live the same day, every day. Bill Murray, at least, found a way out. In Liverpool, we’re still looking.

Truth is, the story could have been about anything – crime, the opening of an arts festival, or an important football match and it could have been published anywhere – The Telegraph, The Guardian, The New York Times or Unherd. It doesn’t really matter what the initial prompt is, as long as the story stays the same. Liverpool, the city, is perennially cast as the troubled lead in a Shakespearean morality play, fuelled by righteous anger, touched by tragedy, let down by treachery, now sadly a watchword for – (insert your favoured macro-political, agenda-driven blank here).

Refreshingly, the Mayor was not too impressed with the New Statesman article. On Twitter, Joanne claimed the writer had “focused on a whole load of scouse stereotypes” and accused him of “lazy journalism”. I found myself in agreement so I reached out to the Mayor for further comment, and to my surprise she replied. What she had to say, for a local Labour leader is, I think, important and worth hearing. But you’ll have to wait a while. You see, first I have this theory and it involves turning our attention inwards. It’s the real meat in this piece. For as much as we might want to blame the media, I believe that the press are, in large part, reflecting back what we as a city put out about ourselves.

Sometimes, our own worst enemy

Compare these two statements. The first is by a journalist, Oliver Brown, Chief Sports Writer at the Telegraph, who was writing about Liverpool’s complex relationship with the establishment in light of some fans failing to observe a minute’s silence to mark the death of the Queen.

“Liverpool is a city that feels that it has been shunted to the margins of British society. It is scarcely an unfounded view.”

The second is from Kim Johnson, MP for Liverpool Riverside who was describing her sense of betrayal at Labour Leader, Keir Starmer writing in the Sun in 2021.

“We are the Socialist republic of Liverpool, a city that marches to the beat of a different drum, a resilient city that will always come back fighting. But we have a long memory and will not forget this betrayal by the leader of the Labour Party, in our Labour city.”

Can you spot the similarities? For starters, they are both quite careless in their use of the collective – back to that sense of the monolithic, singular opinion to represent the Liverpool way. But they also both spoke to something else – a powerful sense of grievance baked into the city identity. Kim Johnson’s quote in particular was the perfect crystallisation of a view that has become increasingly noisy in recent years – the idea that Liverpool is ‘Scouse, not English’ – a place apart, waged in a perpetual battle to get a fair deal, coalescing around some sense of the ‘Other’.

A few weeks back, the Liverpool Echo’s Dan Haygarth, in a quite remarkable article, attempted to explain why so many in the city reject national identity. As explanations go it was comprehensive, yet strangely unconvincing, but it was a perfect reflection of what passes for common sense around here. Supposedly, our 19th-century Irish roots had turned us into ‘rebels’ sceptical of authority; our coastal location transformed us into natural internationalists who looked out rather than in; a history of being ‘let down by the establishment’ first by the Thatcher government in the 1980s and then over the Hillsborough disaster had for many ‘broken the city’s relationship with England beyond repair.’ Throw in the generosity of EU European Objective 1 funding followed by savage post-2010 cuts from Westminster, a Brexit vote that went the wrong way and a nasty article in the Spectator under Boris Johnson’s watch and a seemingly irresistible case was made for a city destined to walk alone.

Haygarth’s article concludes – “The phrase 'Scouse, not English' not only encapsulates Liverpool's civic pride and a healthy rebellious spirit, but expresses a feeling that the city has been so often let down by the establishment of this country. It should come as no shock that large swathes of this Labour-voting, outward-looking, and heavily-Irish city do not feel like they have much in common with the rest of England.”

“They also both spoke to something else – a powerful sense of grievance baked into the city identity… a mutual connection made through the collective swallowing of bitter pills… our loudest voices complicit in the forging of our own myth of alienation.”

For me, the sense of our loudest voices being complicit in the forging of our own myth of alienation is palpable and the justifications horribly deterministic. Who here thinks their life choices and personality are determined by people born 200 years ago? Stitching together disparate events, our public figures and opinion-formers are consciously weaving a narrative that seems to share some of the features of an accelerated national story – one encompassing communal loss and betrayal, a unique sense of difference forged through a mythic connection to lands beyond the horizon and an othering from a surrounding horde of distinctly unsympathetic barbarians. But as foundation stories go, it seems to lack many of the positive elements that make nationhood worth having – with little sense of victories past or historic purpose hard won. Today, it’s hard to look back to our past days as the Second City of Empire with any pride – our fine buildings now come tinged with a dusting of racial guilt. Meanwhile, victories in the class war seem thin on the ground. We are adrift.

What is striking about this evolving story of self, and I must point out that this is about the narrative, not the individual, what is most striking is that it does seem to cohere around a strong sense of grievance for slights endured – a mutual connection made through the collective swallowing of bitter pills made palatable by the odd-football win. Of course, many will simply feel this description does not fit and may take offence at any perceived slight on their scouse identity. But this project to manufacture a sense of separation is very real.

In my view, we are being sold a pup and it’s one that needs to take a trip back to the vet. While we gripe against lazy stereotypes in the media, we are, in truth, guilty of playing to them ourselves and too often take on these restrictive ideas as our own. Liverpool, and I say this with genuine love, is in danger of becoming an addict to its own class-A narrative.

Stuck in the past – where’s our sense of agency?

I’m conscious I need to explain how I think this works and why I believe it’s so dangerous to our health of mind and our future prospects. Let’s go back to that Liverpool Echo article and the popular argument. It has the benefit of simplicity. It goes like this… our sense of grievance, which is legitimately founded, is fuelling our independent, republican spirit, our demand for fairness and our rejection of Englishness, and this is entirely understandable and in some ways positive. It is up to the English and the English alone to make good or we’ll carry on our separate way. Should you be so minded you can buy the mug or the t-shirt and proudly proclaim your support for the Scouse Republic.

Now let me explain what I think is really happening. It ain’t pretty. Strap yourself in. I won’t be winning any prizes for popularity.

My argument is that our sense of grievance is fuelling not a positive assertion of independence but a downward spiral into insularity. The modern sense of political scouse identity that we are being encouraged to adopt, is a perversion of the positive and energetic forms that went before. It is forming primarily around negative assumptions – everyone hates us, we never get treated fairly, we have to fight for everything, and the outcomes that we want are largely beyond our control. There is a sense that the game is rigged against us, feeding a loss of faith in government authority both in Westminster but also increasingly at the local government level too. That’s one of the reasons why we’ve been seeing such low electoral turnouts. After all, if you view things that way, what is the point?

“Our sense of grievance is fuelling not a positive assertion of independence but a downward spiral into insularity. The modern sense of political scouse identity that we are being encouraged to adopt, is a perversion of the positive and energetic forms that went before.”

A primary feature of this outlook is pessimism and a loss of faith in the future. Our belief in our own agency to identify and solve the city’s problems and to conceive of big, ambitious solutions is becoming eroded over time. This is why today, in Liverpool of all places, we feel the pull of the past so strongly, expressed as it is in our stubborn defence of heritage (even when it makes no sense) or our determination to keep fighting old battles long after the social forces that made them have ceased to apply. Looking to the past is simply more reassuring because there is already a map to guide us and our obsession with the 1980s is at least in part, down to this nervousness about our future. It is also a politically convenient way of passing the buck.

As we struggle to find solutions to the problems we face and lose hope of better outcomes, our instinct as proud men and women of Liverpool is to throw our ire outwards, to say, ‘Sod you’ to the rest of England, which as the mooted source of our suffering is cast as the villain (the Scots, Welsh and Irish have our sympathies as they are also considered to be under ‘the yolk’). So then we double down on our own sense of uniqueness - we are hated because we are different - which is mostly a palatable rationalisation of our own sense of defeat. Of course, some people just go away, fire up their belly, and take charge of their lives, for example by setting up a business in places like the Baltic. Others just go away. Meanwhile, as a community, we re-commit to our grievances.