Recent features

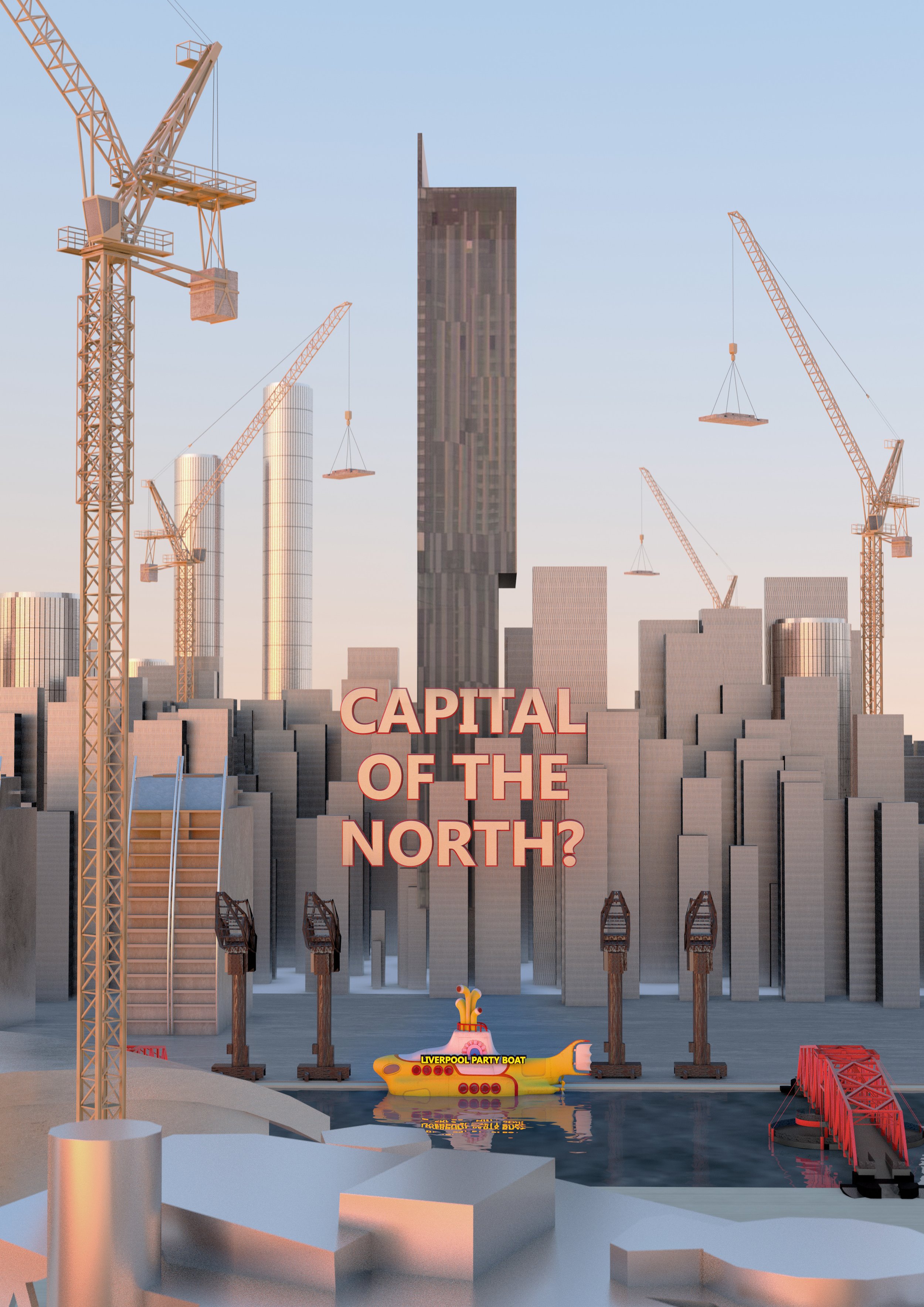

Mancpool: One Mayor, One Authority, One Vision?

Should the city of Liverpool throw in its lot with Manchester and accept one combined North West Metro Mayor to rule us all? Despite admitting that such a suggestion is about as saleable as a One State Solution for Israel-Palestine, Jon Egan thinks it’s an idea whose time has come. It’s certainly an idea that’s provoked some debate within Liverpolitan Towers. But what do you think?

Jon Egan

Manchester Bees Meet Liverpool Super Lambananas by mmcd studio

Is it time the city of Liverpool threw its lot in with Manchester and accepted one combined North West Metro Mayor to rule us all? Jon Egan thinks so. As you can imagine, the suggestion has caused some debate in Liverpolitan Towers and we are not all in agreement. But what do you think? Here Jon makes his case and hints at future initiatives to come…

So let me issue a warning now. This article contains material that many Liverpudlians will find deeply distressing and offensive. It’s an argument that I have tentatively proffered in the past, but after profound and serious reflection, have concluded, now needs to be set out in the most explicit and uncompromising of terms. You have been warned.

David Lloyd’s recent article for The Post lamenting the exodus of Liverpool’s “best and brightest” was as ever an enlightening and enjoyable read, notwithstanding its downbeat and dispiriting narrative of civic and economic decline. If I can add a generational postscript in support of David’s thesis, every member of our youngest daughter’s friendship group from Bluecoat School now lives and works outside Liverpool.

It was the nineteenth century philosopher, Friedrich Nietzche who argued that only as an “aesthetic phenomenon” does the tragedy of human existence find its eternal justification, and perhaps it’s only in the exquisite prose and imaginative virtuosity of David’s writing that Liverpool’s own tragic predicament becomes philosophically palatable. I admire David’s resolute determination to find some tiny component of hope, offered in the city’s joyously ephemeral hosting of Eurovision 2023. But does our capacity for celebration, hospitality and togetherness provide the alchemy for a viable economic renaissance? Does it, at best, illuminate Liverpool’s status as a half-city, stripped of its economic and productive assets, now reduced to the sheer potentiality of its human capital?

The idea of Liverpool as a stage set for cultural spectacles and entertainment extravaganzas (hyperbolically described by the city’s cultural supremo, Claire McColgan as “moments of absolute global significance”), is a beguiling substitute for an actual economy, and an ability to offer a livelihood for the generations who continue to depart for more attractive and seemingly successful cities. It’s a vision that also reminds me of another of Italo Calvino’s magical realist parables in his masterpiece novel, Invisible Cities. Sophronia, the half-city of roller-coasters, carousels, Ferris wheels and big tops, where it is the banks, factories, ministries and docks that are dismantled, loaded onto trailers and taken away to their next travelling destination.

“I fully grasp the deeply heretical nature of this proposition. A ‘One State’ solution for the Liverpool and Manchester City Regions is about as saleable as a one state solution for Israel and Palestine.”

Two hundred years ago, the realisation that we were a half-city inspired Liverpool’s city fathers to contemplate a project that would have world-changing implications - a genuine moment of “absolute global significance”. Prior to the construction of the world’s first inter-city railway, every human journey between major population centres would be dependent on the locomotive capabilities of the horse. Railways were the harbingers of modernity, compressing time and space, and in this instance, connecting one of the world’s great trading centres with its greatest manufacturing hub. Umbilically conjoined, the two half-cities (the place that trades and the place that makes), became the nexus for Britain’s industrial and imperial prowess for the next hundred years.

If the railway brought Liverpool and Manchester closer together, recent decades have been dominated by a football-terrace inspired antagonism aimed at driving us further apart. Liverpool’s antipathy to our more affluent neighbour would seem also to betray more than a slight hint of jealousy, as our rival has greedily accumulated the trappings and status of regional capital.

Rather than resenting Manchester’s success or investing in a strategy of do-or-die competition, is there a smarter and mutually beneficial alternative? Is it time to re-imagine a more symbiotic relationship, that realises that for every British provincial city, the real competition is located 200 miles to the south?

Of course, this is not an original proposition. In the early noughties, Liverpool Leader, Mike Storey and his Manchester counterpart, Richard Leese signed their much lauded Joint Concordat - an agreement only marginally less shocking than the Molotov-Ribbentrop ‘Non-Aggression’ Pact of 1939 between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The benefits were equally short lived. The agreement was conceived in the golden age of regionalism when under the aegis of John Prescott’s mega-ministry - the Department for the Environment, Transport and the Regions - levelling-up and rebalancing were not mere meaningless mantras but core political imperatives. For all its good works, the now defunct North West Development Agency, which once employed 500 people to drive the region’s growth, was more of a hindrance than an enabler for a serious rapprochement between the city’s two main economic players. Determined to uphold scrupulous neutrality between Liverpool and Manchester (it’s Warrington-base memorably described by broadcaster and musical impresario Tony Wilson as being located in the “perineum” of the North West), the agency was forged by a powerful Labour Lancashire mafia, with a brief to prevent and constrain the domineering tendencies of the two cities.

The ill-fated 2001 Joint Concordat between Liverpool and Manchester was only marginally more palatable than the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 which saw the carve up of Poland. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H27337 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

“The idea of Liverpool as a stage set for cultural spectacles and entertainment extravaganzas is a beguiling substitute for an actual economy.”

The Storey-Leese pact conceded Manchester’s status as regional capital, a painful admission of subservience that probably explains the reluctance of subsequent Liverpool leaders to pursue similar overtures. The Liverpool City Region and Greater Manchester devolution deals, and the election of “great mates” Steve Rotheram and Andy Burnham has seen little practical collaboration, beyond occasional media stunts and chummy get-togethers to compare their favourite home-grown pop tunes. Those who expected more than a Northern Variety Hall double act have thus far been disappointed by devolution projects intent on protecting sub-regional domains and denying the compelling reality of geographic and economic interdependence.

We’re two cities less than 30 miles apart, whose fuzzy edges and increasingly footloose populations are blind to civic boundaries that no longer delineate where or how people live, work and play. People are already beginning to see and experience the cities as a single urban place - we just need to dismantle some of the physical and administrative obstacles.

It is beyond farcical that train travel between the two city centres is only marginally quicker today than it was when Stephenson’s Rocket completed its maiden journey two centuries ago. At a pre-MIPIM real estate seminar a few years ago, a Liverpool property professional opined that the single biggest boost to Liverpool’s commercial office market would be a 20 minute train service to Manchester city centre. Who knows, it may even have been enough to persuade Liverpool-nurtured companies like the sports fashion-brand, Castore, to stay in a better connected city location instead of moving to our city neighbour (and taking 300 jobs with it). Questioning the benefits of a fully integrated single strategic transport authority to straddle the two city-regions, is equivalent to advocating the abolition of Transport for London and its replacement by two rival authorities with briefs never to talk to each other.

“Rather than resenting Manchester’s success or investing in a strategy of do-or-die competition, is there a smarter and mutually beneficial alternative?”

For those who ask what’s in it for Manchester, the answer is the well attested and quantifiable benefits of economic agglomeration - cost efficiencies, labour pooling, expanded markets, knowledge spill-overs… Whilst working for the think tank, ResPublica on a project to build the economic case for Liverpool’s connection to HS2, I was staggered to hear Manchester’s economic strategist Mike Emmerich admit that his city envied aspects of Liverpool’s asset-base. The hard and soft criteria by which urban theorists like Saskia Sassen measure the credentials of aspiring global cities, seem evenly dispersed between the twin cities of the Mersey Valley. We can’t match Manchester’s international transport connections, its media and knowledge clusters, but neither can they compete with Liverpool’s global brand, our cultural prowess, architectural grandeur and liveability offer.

If transport is the no-brainer, the wider benefits of agglomeration need to be systematically mapped and identified. The amorphous promise of a Northern Powerhouse can only be realised in physical space, and the contiguity of our two city regions make this the most viable location for a re-balancing project. If the North is ever to grow an economic counter-weight to London, then connecting the two closest jigsaw pieces together seems like a sensible undertaking. Whether its land-use planning or plotting economic development, investment and skills strategies, it’s nonsensical for the two city regions to be pursuing their respective goals in blissful oblivion of what is happening on the other side of an arbitrarily contrived line on a map.

Notwithstanding, its invaluable enabling role in gap funding development and infrastructure projects, the North West Development Agency was a political creation without underpinning logic or legitimacy. Were there ever any connecting threads of economic interest between Salford and Penrith? Wilmslow and Barrow-in-Furness? The Agency’s opaque governance, and its tortuous high-wire balancing act, placating a multiplicity of sub-regional agendas and interest groups, inhibited its ability to optimise the potential of the region’s two great economic engines.

So here comes the controversial bit. Pacts, concordats and convivial personal relationships are simply not sufficient to realise the potential of a new economic relationship between the two city regions - one that acknowledges that their respective asset-bases can be curated for mutual benefit. The only solution is a new governance structure - a devolution model with one Metro Mayor and one Combined Authority. I fully grasp the deeply heretical nature of this proposition, and the threat that it seems to pose to the identity and autonomy of a city that suspects it will be the junior player in any such arrangement. But are identities any more compromised in a ‘Twin City Region’ than they are within the current dispensation? St Helens, Sefton, Wirral, Wigan, Bolton amongst others would probably argue not. The integrity and jurisdiction of the respective city councils and other local authorities would not be compromised - we would only be pooling functions and responsibilities that are already acknowledged to be regional, and projecting them onto a bigger and less artificially contrived regional canvas.

“The only solution is a new governance structure - a devolution model with one Metro Mayor and one Combined Authority.”

Once upon a time, Liverpool and Manchester were authorities under the even more commodious administrative umbrella of Lancashire County Council, and as I‘ve mentioned, more recently, through the North West Development Agency, we were content to buy into the concept of a North West regional project conspicuously lacking any democratic accountability.

In a Twitter / X exchange with Liverpolitan a few weeks ago, I was asked to defend this joint governance proposition by pointing to a successful or established similar model elsewhere in the world. In the US, the twin cities of Minneapolis and St Paul, and of Dallas and Fort Worth, and the urban centres of the San Francisco Bay Area have come together in different ways to pool planning, transportation and economic development responsibilities. Closer to home, the Ruhr Regional Association in Germany exercises both a statutory and enabling role in areas including planning, infrastructure, economic development and environmental protection for the cities of Dortmund, Duisburg, Essen and Bochum. But even if there is no precise template elsewhere, should this be an inhibitor to the cities that built the world’s first inter-city railway, and that pioneered many of the most progressive advances in civic governance in the 19th and early 20th centuries?

In the absence of compelling practical arguments against the proposition, the most likely and persuasive objection will be that the mutual rivalry runs too deep, the antagonism is simply too intense and has festered too long. A ‘One State’ solution for the Liverpool and Manchester City Regions is about as saleable as a one state solution for Israel and Palestine. Maybe it’s an argument that requires a solution or a process rather than a rebuttal. In truth, antipathy is a quite recent addition to a history of rivalry that owes more than a little to the intensity of the competition between the country’s two most successful football teams. Exorcism perhaps requires a practical project, an enthusing collaboration that focuses on shared cultural attributes and ambitions. Somewhere not far away such an idea is maturing, but I will leave it to its progenitors to expand, perhaps on this platform, and maybe very soon.

Of course, there is another motive and spur for this idea which relates to the abject failure of governance within the city of Liverpool and the continuing inability of its dysfunctional political class to nurture or curate those incipient possibilities that so rarely reach fulfilment. The uprooting of Castore from Liverpool to Manchester is an instructive case study, but so too are the games companies, the biotech businesses, legal and insurance firms that have hatched in Liverpool and gone on to prosper elsewhere. Maybe we need governance less rooted in parochial politics and less constrained by cultural legacy. To borrow an analogy from Iain McGilchrist’s Divided Brain hypothesis, perhaps Manchester’s busy-bee utilitarianism and non-conformist pragmatism is the left hemisphere counterpoint to Liverpool’s wistful dreaminess (even our civic emblem is an imaginary being). Is it just possible that our divergent dispositions and outlooks are not actually a prescription for unending antagonism but the formula for a fruitful alchemy?

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

The Beatles: Inspiration or dead weight?

When does city pride in the Fab Four turn into a hindrance to future achievement? Jon Egan argues that the city of Liverpool is in danger of becoming a Beatles theme park, and its world conquering band a crutch to exorcise the painful intimations of our diminished relevance and prestige. In looking to the past, have we forgotten what made John, Paul, George and Ringo so special - their fearless embrace of the avant-garde, the contemporary and the new?

Jon Egan

There was something profoundly true and desperately sad in University of Liverpool lecturer, Dr David Jeffery's acerbic observation that "Liverpool is a Beatles' shrine with a city attached."

It is the dispiriting obverse to music journalist, Paul Morley's rhapsodic description of Liverpool as "a provincial city plus hinterland with associated metaphysical space as defined by dramatic moments in history, emotional occasions and general restlessness."

Jeffery's comments on Twitter appear to have been inspired or provoked by the recent announcement that Liverpool would be using a £2 million grant from Government to advance the business case for yet another "world-class" and "cutting-edge" Beatles' attraction on our hallowed waterfront. Presumably, it will be sandwiched somewhere between the Beatles statue and The Beatles Experience and conveniently close to The Museum of Liverpool and The British Music Experience with their not inconsiderable collections of Beatles artifacts and memorabilia. The exact nature of this new cultural icon remains a little unclear, however, amidst wildly differing descriptions offered by our City and Metro Mayors.

What is deeply depressing about this announcement is that it suggests that Liverpool is incapable of imagining any kind of cultural proposition that is not predicated on the seemingly inexhaustible allure of the four boys who shook the world.

There is of course a readily available and seemingly plausible justification for the never-ending Beatles' fetish, and that is the claim that they are the anchor for our hugely important tourism economy. Notwithstanding the implication that David Jeffery is right to suspect that the city is consciously morphing into a Fab Four theme park, I suspect that this is not exactly the whole truth. For Liverpool, The Beatles are a crutch, a cherished emblem of identity and importance used to exorcise painful intimations of diminished relevance and prestige.

In the novel, Immortality, Czech writer Milan Kundera tells the story of the man who fell over in the street, who on his way home stumbles on an uneven pavement, falls to the ground and arises dazed, grazed and dishevelled, but after a few moments composes himself, and gets on with his life. But unbeknown to the man, a world famous photographer happens to witness the scene and quickly snaps an image of the bewildered and bloodied pedestrian. He subsequently decides to make this picture the cover image for his new book and the poster for his international exhibition. For the man, a momentary misfortune freeze-framed, replicated and disseminated across the world, becomes the image that will forever define who he is.

The more we conflate the Beatles brand with the city's identity, the less space we have to imagine anything original, contemporary or remarkable.

In a sense, Liverpool is the City that fell over on the street, our external image is in significant part, defined by a succession of misfortunes, afflictions and tragedies that befell the city over two decades at the end of the last century. These events forged images, preconceptions and stereotypes that still blight us today and have never been successfully exorcised or replaced.

The Beatles hark back to a time before this blight, when Liverpool was in Alan Ginsberg's celebrated phrase, "the centre of consciousness of the human universe." They are, I believe, a therapeutic distraction from the task of making a different story or discovering a new identity.

Culturally, our Beatles fixation is unhealthy, debilitating and regressive. In fact, I fear we are reaching a point where The Beatles will become the single biggest impediment to any form of civic progression, or any serious project to make Liverpool important, interesting or relevant in today's world. If we are going to have a civic conversation about what kind of "world class" Beatles attraction should be erected at The Pier Head, my immediate impulse would be to recommend a mausoleum.

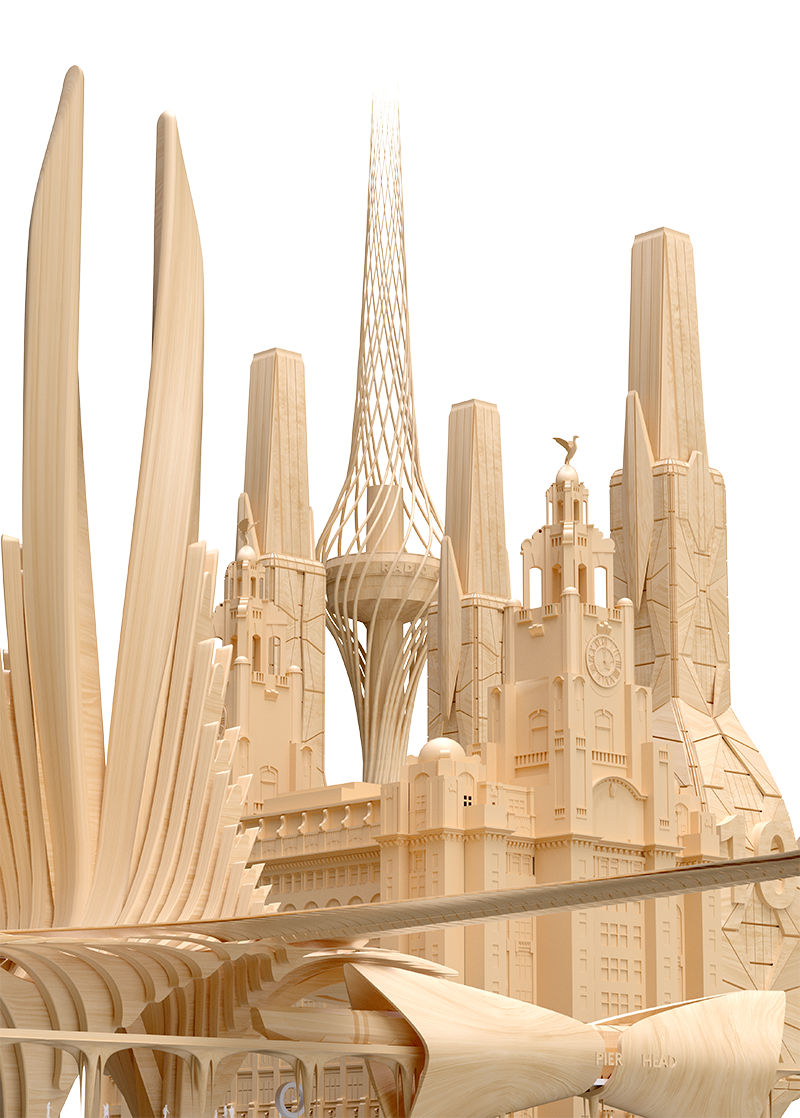

But perhaps a more imaginative and original idea was the one offered by the late Tony Wilson. That supreme Mancophile, Factory Records producer, Granada TV reporter and founder of the Hacienda nightclub was never held in particularly high regard in this city, especially following some tongue in cheek words of encouragement he gave to Club Brugge on the eve of their European Cup semi-final with Liverpool in 1977. Scousers may resemble elephants with respect to their prodigious powers of memory, but our skins can sometimes be just a tiny bit thinner. Tragically, Wilson's Mancunian persona and his tendency to lapse into casual profanity whilst presenting his project to civic decision-makers proved the undoing of his brilliant and visionary proposition for POP - the International Museum of Popular Culture. Pitched as the big idea for the European Capital of Culture, and the solution that would provide content for Will Alsop's audacious but otherwise functionless Fourth Grace, POP was a talisman for instant reinvention - a Beatles-inspired attraction without any reference to The Beatles. Alas it never happened.

Wilson had first dreamt of POP as an adornment for his own native city and a fitting celebration of its notable contribution to the history of modern popular music, but he soon realised that it was the right idea for the wrong place. He would often express irritation that when travelling in the US he would frequently have to explain where Manchester was by reference to its proximity to Liverpool - a place that people had actually heard of. And there was also the grudging recognition that at a time when Liverpool was "the centre of the human universe" globalising popular culture - Manchester could only offer us Freddy and The Dreamers. Even the outrageous charisma of Manchester United football god, George Best was derivative as he was often dubbed the 5th Beatle.

POP would not simply have been about popular music, it would encompass every facet of popular culture, every expression of contemporary creativity in film, TV, advertising, games, cars, sport, fashion, digital technology and consumer culture. And it was proposed for Liverpool because this was the place that spawned a phenomenon that reached the four corners of the Earth. It was a moment when the world discovered a common currency and a cultural vernacular intelligible to every ear.

POPs content would be dynamic and ever-changing, a continuous exposition of the new, curated by global creatives, designers and technologists. It would be Liverpool recovering its world city perspective and its capacity to invent and innovate - the pool of life, the birth canal for the extraordinary and the unprecedented. Its ingenious paradox was its implicit assertion that The Beatles did not make Liverpool, but Liverpool made The Beatles.

They monopolise our self-image occluding facets of identity and history now only half-glimpsed in the penumbra of a shadowy scouse dreamtime.

All of which is a million miles from Steve Rotheram's "world-class immersive experience" which he promises us will be more spectacular than a glass cabinet containing John Lennon's underpants. We can hardly wait.

If all we can possibly imagine are The Beatles etherealised into holograms - almost literally spectres from beyond the grave - then David Jeffery is right and Liverpool's once rich and cosmopolitan culture has collapsed into a black hole of redundant clichés. The more we inflate our Beatles offer and conflate their brand with the city's very identity, the less space we have in which to imagine anything original, contemporary or remarkable. Along with football (which at least tells new stories) they have come to monopolise both our external brand and our officially curated self-image, occluding facets of our identity and history that are now forgotten and suppressed, only half-glimpsed in the penumbra of a shadowy scouse dreamtime.

The Beatles have come not only to represent our brand, but have also helped to define our personality, attitude and accent - cheeky, chippy, sassy and defiant. As emblems of the 60s social revolution, they helped to forge and reify the idea of Liverpool as a working class city - or more accurately an exclusively working class city. As rock journalist Paul duNoyer, notes in his book, Wondrous Place, this is both a false and profoundly disabling imposition. Not only, as Tony Wilson asserted, are we the city that globalised popular culture, but we are a city that has contributed massively to every facet of culture, ideas and invention over the last 200 years.

The world's first enclosed dock and inter-city railway, together with the completion of the Transatlantic telegraph cable, are not only stunning achievements in technological innovation, but bolster the credible claim that globalisation began here.

The extent to which we have been willing to squander or disown the breadth of our cultural heritage was brought home to me in the febrile final stages of the European Capital of Culture bidding competition. Having commissioned pop artist, Sir Peter Blake to create a homage to his iconic Sgt Pepper album cover to remind the world, or at least the judging panel, of Liverpool's cultural and intellectual prowess, the task of deciding who exactly was worthy of inclusion was both fraught and enormously revealing. Apart from a few contemporary, and at the time highly topical creatives including the poet Paul Farley, artist Fiona Banner and film-maker Alex Cox, the principal criterion for inclusion appeared to be the directness or intimacy of connection to The Beatles. A lop-sided bias towards musicians, popular entertainers and Sixties icons meant no room for the likes of painters George Stubbs and Augustus John, poets Nathaniel Hawthorne and Wilfred Owen, novelist Nicholas Monsarrat, playwright, Peter Shaffer or even poet and novelist, Malcolm Lowry the author of the celebrated, Under the Volcano. Incredibly, until Bluecoat Artistic Director, Bryan Biggs' finally succeeded in persuading Wirral Council to erect a blue plaque on New Brighton's sea wall, there was virtually no public recognition that one of the 20th century's greatest and most influential novelists had any association with the Liverpool City Region.

Without questioning or diminishing the impact of the Mersey Sound poets (McGough, Henri and Patten) in the 1960s, their literary status is no way comparable to another unsung and forgotten cultural luminary with a significant Liverpool connection - C.P. Cavafy. Now acknowledged as one of the last century's most important and original poetic voices, Cavafy spent much of his childhood at addresses in Toxteth and Fairfield. Greek and gay, his poetry will forever be associated with the city of Alexandria where his family settled after leaving Liverpool. We do not know to what extent his formative years in the city helped nurture Cavafy's creative animus, but transience, up-rootedness and departure are woven into our narrative. Our sense of self and place in the world as Liverpolitans, owe as much to those who moved on, or merely passed through, as they do to those who stayed or settled here.

We are not, and never have been a monochrome canvass or a one trick city. Our culture is dense, deep and multifarious, formed by a hotchpotch of races, creeds and classes. For those tasked with defining a place and communicating its uniqueness to the world, there is always the temptation to reduce and simplify.

Brands, including place brands, are often conceived like Platonic forms - a distilled essence, fixed and immutable. But cities like Liverpool are neither simple nor static, and are thus frustratingly un-brandable. Described by Wilson as a place with "an innate preference for the abstract and the chaotic," our essence is pre-Socratic - unresolved, unpredictable and disconcerting. We know that port cities like Liverpool, Naples, Barcelona and Marseilles have historically been melting pots for ideas, influences and cultures - places where things never quite settled.

But their edginess is not merely a function of a perturbed diversity, it is also literal. It's connected to Marshall McLuhan's philosophical idea of right hemisphere sensitivity and the expanded perspective of what he terms acoustic space. Ports face outwards, they are perched on the precipice of a vast and formless abyss. It's an omnipresent reminder that there are no limits.

For Paul Morley, Liverpool’s character and identity - its ability to charm, entertain, inspire and infuriate - proceed from an inchoate restlessness and fidgety creativity. It's a place "where something happens, most of the time, leading to something else." But it seems like that creative energy and inventiveness have deserted us - or at least our leaders. What was once an animating pulse has been reduced to a piece of hollow rhetoric - a brand attribute.

It's sad that a UNESCO City of Music should have forsaken polyphony, and that we are continually stuck in a repetitive groove, narrowing our identity and stifling our capacity to be original (again). For this reason the very last thing Liverpool needs is yet another Beatles' attraction, even an immersive one.

So, OK, The Beatles were important, are important. They changed the world, but did they change Liverpool? We're still, I hope, the city capable of creating something else.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

Life after Joe: Ditching the Mayor won’t fix our broken democracy

There’s something nearly all of Liverpool’s political parties agree on - the need to abolish the office of directly elected city mayor. But are their positions based on principle, self-interest or just faulty logic? In 2022, the public should get to decide the question for itself in a referendum, but with such a one-sided campaign in prospect, there’s an acute danger that we’ll sleep walk into this vote without the chance of a properly informed debate.

Jon Egan

When nearly all of Liverpool’s political parties agree on something, you can bet it’s on an issue of mutual self-interest rather than in defence of any cherished principle.

As things stand, Liverpool’s voters will be invited, most likely in 2022, to decide whether to keep or dispense with the office of directly elected city mayor. It promises to be a rather one-sided campaign with the city’s three largest political groups (Labour, Liberal Democrats and Greens) all arguing for abolishing the post and returning to what they collectively describe as the “more accountable” Leader with Cabinet structure.

Even our recently elected incumbent, Mayor Joanne Anderson, is pledging to vote for the abolition of her own job, which begs the question, why she was so anxious to run for office in the first place? But of course, she was not alone. In the 2021 mayoral election, only two candidates - the Independent, Stephen Yip, and the Liberal Party's Steve Radford - were actually standing on a pro-mayor ticket. Indeed, following the unprecedented intervention by Labour's ruling National Executive to disqualify all three of the senior councillors on the original selection shortlist, both the Labour and Liberal Democrat council groups attempted to cancel the election by abolishing the role without recourse to a public referendum, until they were stopped in their tracks by polite reminders from their own legal officers that such a move would be unlawful.

There is an acute danger that we will sleep walk into this referendum without either a campaign or a properly informed debate. Voters will be asked to reflect on the need to learn lessons from euphemistically labelled "recent events" and fed the seemingly plausible line that one mayor is better than two. After all, why do we need a city mayor now that we have a metro mayor?

Of course, there is a shadow hanging over this whole discussion – one powerful argument for the case against elected mayors – which comes in the shape of the now under investigation and widely discredited former mayor, Joe Anderson. For some, he has become a walking metaphor and deal-sealing symbol of the dangers of too much power in the hands of one larger than life individual. But this is too important a decision for knee-jerk reactions. Our democracy demands that the subject be properly examined and debated. It’s too easy for us to be seduced by over-simplified and questionable arguments. We should think hard before dispensing with a model, that I would contend, has never been properly embraced or tried by our local politicians.

There is an acute danger that we will sleep walk into this referendum without either a campaign or a properly informed debate.

Before we head off to the ballot box (presuming we get the chance), there are some key questions we have to consider. Are mayors generally a good thing? Can they achieve results that old-style council leaders can't? Is there something specifically about Liverpool and the state of our local governance, our politics and our economic and social predicament that makes having a city mayor here particularly desirable or dangerous? And how are we to make sense of our experience of the mayoral model to date? Are the critics right that the concentration of power has been unhealthy or even corrupting?

But first… a little context. Let’s delve back into the city’s recent history to find out how we ended up in this mess. City mayors were an early prescription for what is now fashionably described as ‘levelling-up.’ The problem of a seriously unbalanced economy and underperforming urban centres was a matter of serious priority for the incoming New Labour government in 1997. The publication of Towards an Urban Renaissance - the report of Lord Rogers' Urban Task Force was a seminal moment in re-prioritising the importance of cities as vital engines for growth, innovation and national prosperity.

We’ve been here before - Liverpool’s democratic deficit

Harnessing that growth, it was implied, would require a new kind of energised civic governance similar in form and style to the dynamic leadership that had successfully regenerated European and North American cities such as Barcelona and Boston. In contrast, the fragmented committee structure of local government, then dominant in the UK, was seen as a recipe for old-school inefficiency and a failure of imagination. A new Local Government Bill (2000) set out the options to reset civic democracy. There was no coercion; just three choices: Leader and Cabinet (close enough to stay as you are), and two flavours of the big bang option for directly-elected City Mayors. Towns and cities were free to decide for themselves and unsurprisingly, councils overwhelmingly chose the least change option with only a handful willing to embrace the more radical mayoral restructure.

In Liverpool, however, the idea of a directly elected mayor aroused immediate interest, though admittedly not amongst our politicians. Instead, the city's three universities, its two largest media organisations (BBC Radio Merseyside and the Liverpool Echo) and a collection of faith leaders convened the ground-breaking Liverpool Democracy Commission in 1999. Under the chairmanship of Littlewood's supremo, James Ross, the independent commission brought together politicians, academics, and community and business leaders such as Lord David Alton, Professor of Urban Affairs, Michael Parkinson (now of the Heseltine Institute), radio presenter Roger Phillips, and Claire Dove, a key player in the local social enterprise movement. They took evidence from national and local experts and were shadowed by a Citizen's Jury to widen representation. In turn, the city council made a commitment to consider its recommendations and, if a mayoral model was advocated, to hold a public referendum.

From its inception it was clear that the commission was not simply evaluating the general merits of the available models, but was considering their applicability to Liverpool’s very particular local circumstances. Those circumstances included a wretched turnout of just 6.3% when a tired and divided Labour administration lost its majority in the crucial Melrose ward council by-election in 1997, the lowest ever poll in British electoral history. A Peer Review of the troubled council at the time by the Independent and Improvement Agency had painted a picture of lethargy, cronyism, an insular town hall culture, and wretchedly poor service delivery. Liverpool was acutely aware that its civic governance required a radical reboot.

Leaders run councils, Mayors run cities

The more general case for a directly elected mayor centred on its ability to reinvigorate local democracy, transferring the focus of civic leadership from the inner minutiae and manoeuvrings of the town hall to the wider city – its communities, businesses and institutions. As local government academic Professor Gerry Stoker put it when giving evidence to the Democracy Commission, “Leaders run councils, mayors govern cities.”

Stoker was by no means alone in advocating this radical change. Evidence from witnesses, community meetings, public surveys and the Citizen’s Jury converged on the same transformational proposition. Mayors could be convenors, able to galvanise civic energy by bringing multiple parties together in partnership. They would change the destiny of places in ways that our stilted and bureaucratic town halls could never hope to emulate.

Against this backdrop, the idea of giving every citizen the opportunity to vote for the city's leader seemed refreshingly progressive. It also offered a tantalising possibility - a radical break with party politics. Theoretically, the elected mayor system provides a level playing field for independent candidates. No longer would political parties with the networks and infrastructure required to support candidates in all of the city's wards be able to monopolise the system. Politics could be open, unpredictable and much more interesting and the talent pool from which to select a city leader was immediately expanded. Clever and experienced people from business and civil society would step forward to offer themselves for election.

But above all, it was the radical simplicity of the democratic contract that commended the mayoral model. No longer would local democracy be transacted behind closed doors, shrouded by arcane traditions and enacted through the inscrutable election-by-thirds voting system that somehow allowed political parties to lose elections but miraculously stay in power. With a directly-elected mayor, there would be visible leadership, clear and simple accountability and a transparent means of returning them or removing them from office.

By blaming the mayoral model for the shameful abuses and failures identified by Caller, our councillors are indulging in a transparently hollow attempt at self-exoneration.

It was for that reason that elected mayors were pitched as the antidote to voter disaffection, not just in Liverpool but across the whole country. Turnouts for local elections were in decline everywhere resulting in a widely acknowledged crisis of legitimacy.

Legitimate or not, one year before the Democracy Commission was founded, Liverpool’s voters had their say, overcoming their most ingrained cultural instincts to throw out what they knew was rotten. Liverpool's Labour administration was swept from power by an almost entirely unpredicted Liberal Democrat landslide.

So it would be a Liberal Democrat administration that would decide whether to adopt the mayoral model and respond to the unequivocal recommendation of The Democracy Commission. But they fluffed their lines, embracing instead the less radical option offered by the New Labour government – a Leader with Cabinet. Not for the first time, our political leaders knew best. Rather than allowing voters to choose their preferred model via the referendum they had promised, the council opted for the one that suited their own ends best.

Paradoxically, Liberal Democrat Council Leader, Mike Storey’s style and swagger were almost mayoral. He set up the UKs first Urban Regeneration Company (Liverpool Vision) and boldly calibrated a vision of the city as a European Capital of Culture. These were heady days, and many will now look back nostalgically on Storey’s early tenure as a time of almost limitless promise. So what went wrong?

Storey was instinctively attracted to the idea of city mayors and thought he could be one without having to navigate this dangerously Blairite and centralising heresy through his notoriously individualistic and anarchic Liberal Democrat Party. But Storey was constrained both by the instincts, prejudices and personal ambitions of his own political group, but perhaps more importantly, by the absence of an independent democratic mandate. His leadership rested on the confidence and acquiescence of his unruly Lib Dem caucus, but also on the compliance and co-operation of his highly ambitious Chief Executive, Sir David Henshaw - a challenging job at the best of times. From the outset, some had feared being left out in the cold by this high profile vote winner and knives were sharpened. Without a personal mandate from the public, it was difficult for Storey to face them down. The image of a beleaguered leader imprisoned and frustrated by an obstructive town hall bureaucracy was painfully and comically exposed in the infamous "Evil Cabal" blog. This was local government reduced to camp farce.

The fact is, Storey’s leadership and authority waned precisely because he was not a mayor. He lacked the clear constitutional and democratic authority to deliver on his mandate and to prevail over vested interests and personal agendas. At the end of the day, he was too much a part of a system that was still instinctively protective and self-serving.

Where power really lies

This may appear to be a subtle and rather academic distinction, but the source of a council leader's authority is always municipal rather than civic. The democratic process is indirect and opaque, and real power rests with councillors, not voters. It is councillors who choose the leader, and it is councillors who can topple them, even outside of the local election cycle. Ultimately, council leaders know who they are answerable to and are inclined to act accordingly.

Eventually Storey was forced to resign and after his nemesis, Henshaw, had departed, the Liberal Democrat regime lapsed into a familiar pattern of failure and chaos, mimicking its Labour predecessor. Before long it was being tagged as the country’s worst performing council, and was dumped out of office by an unlikely Labour revival. The compromise option of The Leader with Cabinet model had not ushered in the promised golden age of civic renewal, but only dismal continuity and an all too familiar story of town hall intrigue and ineptitude.

For the incoming Labour administration, the mayoral option was perceived as a threat, not an opportunity. Liam Fogarty’s Mayor for Liverpool campaign was gathering steam, and its petition heading towards the tipping point where a public referendum would have to be negotiated. For Fogarty, the slow implosion of the previous Liberal Democrat administration was evidence that the problems were systemic. He believed that only a new model which transferred more power to voters could fix Liverpool's dysfunctional municipal culture, and that the authority of leaders must rest on a direct personal mandate from the public.

Fearful that a referendum campaign would be a platform for a powerful independent, and in an act of supreme cynicism, Joe Anderson invoked a hitherto unsuspected provision of the Local Government Act to transform himself into an “unelected” elected mayor. It’s worth remembering that Labour’s adoption of the model was motivated solely by a neurotic phobia of a Phil Redmond (creator of popular TV soap-opera, Brookside) candidacy, rather than any intrinsic attraction to this radical new way of running a city. In truth, Liverpool Labour never believed in elected mayors and the shambles and shame of Anderson’s last days provided it with a perfect opportunity to dispatch the idea once and for all.

Boss politicians and the school of hard knocks

Anderson's sleight of hand once again deprived Liverpool voters of the opportunity of a referendum where the mayoral model could have been properly debated and explored. The fact that it was adopted without enthusiasm or any thorough consideration of its merits, is perhaps the explanation for what subsequently transpired. Anderson did not rule as a convening mayor - as envisaged by Stoker and advocated by the Democracy Commission - dispersing power, building coalitions, and using soft levers to nurture civic cohesion. He was an old-style Labour “City Boss” – in the style and tradition of Derek Hatton, Jack Braddock, Bill Sefton and a host of less memorable and notorious predecessors. Anderson’s approach was that of a fixer and deal-maker - a pugnacious “school of hard knocks” political operator who once threatened to punch a Tory Minister on the nose for claiming that austerity was over.

If Mike Storey was a council leader masquerading as a mayor, Joe Anderson was a mayor acting out the role of a traditional boss politician. What Storey lacked in terms of authority and mandate, Anderson lacked in terms of subtlety, collegiality and an overarching civic perspective.

During a mayoral hustings event in 2012 at the Neptune Theatre, an audience member posed the challenge, what is Liverpool for? A tricky question and one that demanded a perspective beyond the familiar horizons of the council budget and Tory assaults on its finances. Anderson seemed utterly dumbfounded. Only Liam Fogarty was able to grasp that existential questions like these cannot even be perceived, let alone resolved, from the myopic vantage point of a town hall bunker. Our politicians were simply incapable of rising to the challenge of a political role that required a radically different set of skills and a civic, rather than a municipal, mindset.

Which brings us to today. In effect, we have had a mayoral model, but we have never had a mayor in the way it was envisaged… as a radical antidote to a broken town hall culture.

It is the supreme irony that the case against elected mayors is now being framed on the record and reputation of Joe Anderson - the very embodiment of old-style Liverpool municipalism with its narrow and insular perspective. The argument that Anderson proves the perils of placing too much power in one person’s hands is a dangerous and misleading sleight of hand; a fallacy designed to obscure both historic truth and the complex considerations that should be informing this hugely important debate about how our city is governed.

The fallacy was set out quite pointedly in the 2021 Max Caller report, with its forensic exposure of Liverpool Council’s systemic municipal failure. In describing the governance structure of the city council, Caller observed:

“although the mayor is an authority’s principal public spokesperson and provides the overall political direction for a council, an elected mayor has no additional local authority powers over and above those found in the leader and cabinet model, or the committee system.”

Mayors are a dangerous idea. Independent candidate Stephen Yip threatened to end party political hegemony in Liverpool with only the meagrest resources. This is an eventuality that establishment politicians must join forces to thwart once and for all.

In effect, the "Leader with Cabinet" model now favoured by our local politicians, places exactly the same amount of power in precisely the same number of hands as the “discredited” mayoral model. In no way is it inherently more accountable or transparent. We are being sold a false prospectus, and one we know from our own recent history is no panacea. This is the classic ruse of the second-hand car salesman, and we need to look under the bonnet before it's too late.

By blaming the mayoral model for the shameful abuses and failures identified by Caller, our councillors are indulging in a transparently hollow attempt at self-exoneration. The “few rotten apples” alibi became the recurrent mantra to explain away the systemic dysfunctionalism exposed by the report. It was all down to the Mayor and a system that allowed a few powerful individuals to operate without adequate transparency or scrutiny. Or so the story goes. The solution is simple, get rid of the Mayor and all will be well.

But there was nothing extraordinary or atypical in Anderson's style, nor anything that was especially mayoral about the municipal culture or the way power was exercised. Caller's report is depressingly redolent of the Peer Review into the previous failed Labour administration and the chaotic end days of the subsequent Liberal Democrat council. This is simply what Liverpool local government looks like.

Multiple Mayors - other cities seem to manage it

We cannot make the mayoral system a scapegoat for a chronic and systemic failure of governance in our city. If, as its critics allege, mayors necessarily lead to an undesirable and dangerous concentration of power, then logically, wouldn’t we also need to seriously revisit our devolution deal and the post of Metro Mayor? Our politicians can’t have it both ways.

And neither should we be spooked by the “too many mayors confuse the voters” line. If it turns out that mayors are a good thing after all, then why should they be rationed? Mayors and Metro Mayors co-exist happily in London, Greater Manchester, South Yorkshire, the West of England, Tees Valley and North of Tyne. Cities in these areas including Bristol, Middlesbrough and Salford appear to be able to cope with the idea of different mayors exercising different powers over different geographic jurisdictions.

We shouldn't of course be surprised that our politicians are advocating for a return to the Leader with Cabinet system, when its most conspicuous difference to the “disgraced” mayoral model is that it would give them the exclusive power to decide who our City Leader should be. Rather than a direct popular mandate, Liverpool’s leader would be entirely beholden to councillors from within their own political group. Only in the looking-glass world of Liverpool politics can this be presented as more democratic and accountable. As the elected Mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees recently argued in response to those advocating abolition of the post there. “It doesn't take much understanding of why the old system didn't work. Anonymous and unaccountable leadership, decisions made by faceless people in private rooms, and a total lack of leadership and action. The mayoral model makes the leader accountable - he/she is elected by the people of Bristol directly, not by 30 people in a room as in the old committee structure.”

If Liverpool votes to abolish its elected mayor and reverts to a system that has already proven unfit for purpose, we will weaken local democracy and diminish accountability.

But this is precisely the brave new system that we will be invited to endorse in next year's referendum and one that has already been tried and found wanting.

The lesson is that having an elected mayor is not a sufficient condition to deliver radical civic and political change, but it is a necessary one. The authority, legitimacy and wider perspective of the mayoral office is vitally important in making our municipal edifice work for the city rather than for itself.

Mayors are a good idea because they provide visible, directly accountable leadership. Their mandate enables them to speak up for their locality with authority and influence. We only need to look to London and Greater Manchester to see how mayors have been powerful and effective advocates for their cities and regions. But ultimately we need one who understands and actually believes in the role, which is why it is difficult to believe that Joanne Anderson's tenure is likely to fulfil the potential that the post could still offer to the people of Liverpool.

But as our councillors understand only too well, mayors are a dangerous idea. Independent candidate Stephen Yip threatened to end party political hegemony in Liverpool with only the meagrest resources and virtually no grassroots organisation. This is an eventuality that establishment politicians must join forces to thwart once and for all.

If Liverpool votes to abolish its elected mayor and reverts to a system that has already proven unfit for purpose, we will weaken local democracy and diminish accountability. And we’ll be doing it in the name of its opposite, bamboozled by the Humpty Dumpty logic of Liverpool politics where words mean whatever our politicians choose them to mean. We will also denying ourselves even the faintest possibility of breaking out from the cycle of dysfunctional party politics.

The elected mayoralty is the only chance we have to change the way our city is run. The tragedy is, we could lose this opportunity before ever having really given it a proper go. Someone needs to start a campaign, and soon.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.