Recent features

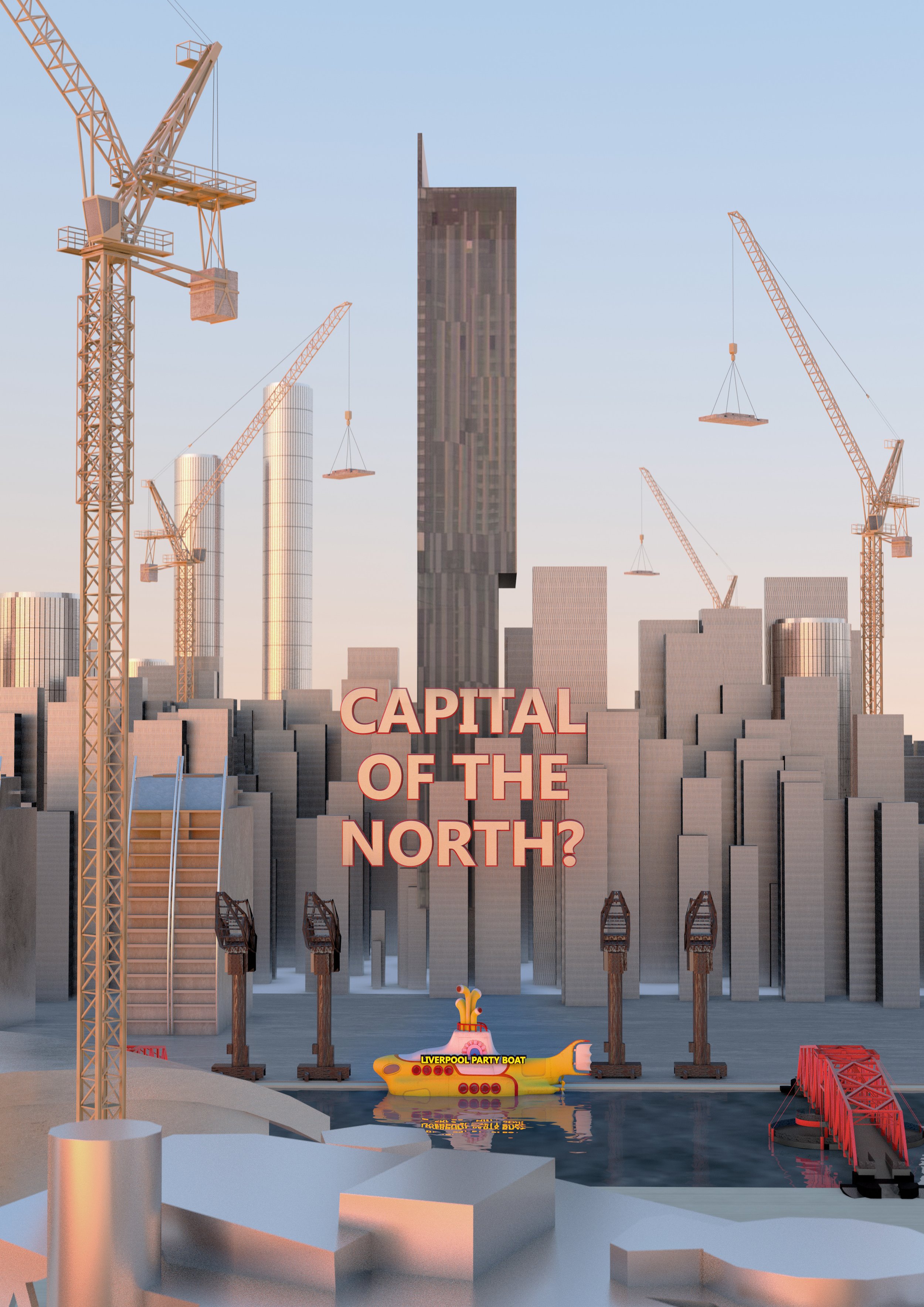

HS2 Cuts: A Second Chance for Liverpool

As we wave goodbye to any ideas of HS2 reaching the north, a deafening chorus of betrayal is drowning out attempts to assess the project’s worth more rationally. Yet the inconvenient truth is that many in the north have never been convinced of the value of HS2. In this article, Martin Sloman, a director at influential lobby group, 20 Miles More, asks whether the HS2 re-set is a golden opportunity for Liverpool - a second chance at creating new transport infrastructure that works for our city?

Martin Sloman

As we wave goodbye (at least for now) to any ideas of HS2 reaching the north, a deafening chorus of betrayal is drowning out attempts to assess the project’s worth more rationally. Yet for all that, there is an inconvenient truth displayed every time a BBC journalist puts a microphone in front of the general public - the existence of a clear disconnect between the project’s advocates and your average paying train passenger. Lord Adonis may cry foul but many in the north have never been convinced of the value of HS2. In this article, Martin Sloman, a director at influential lobby group, 20 Miles More, considers the matter from Liverpool’s perspective. He asks the question, is the HS2 re-set a golden opportunity - a second chance at creating new transport infrastructure that works for our city?

And so there it is. HS2 beyond Birmingham has gone the way of the Dodo. It is no more. It has ceased to be. It is an ex-railway.

Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak’s much trailed announcement at the Conservative Party Conference to hack back the UK’s largest public transport project represents not just a big throw of the political dice, but a huge scaling back of HS2’s ambitions. Unless you believe a Starmer-led Labour government will revive the scheme (don’t bank on it), the line will no longer extend to Manchester, instead terminating at Birmingham, the place that likes to call itself ‘the second city’. Brum’s claims have been bolstered now. This news is seen almost universally amongst the commentariat as a body blow to the much-vaunted ‘Levelling Up’ strategy, but what does it mean for Liverpool and our city region? Should we see it less as a disaster for the north and more as a second chance to get our city’s transport infrastructure right?

Liverpool came late to the HS2 debate. It was only after the Phase 2 proposal was revealed in January 2013 that we began to realise how the project would affect us. By then, the route was set in stone, and it didn’t look good. The new line was designed as if Liverpool didn’t exist. There would be stations at Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Airport, a lengthy tunnel into Manchester city centre and a link to the north via Wigan. Liverpool would be lucky to get new, plastic platform seating.

Under the HS2 plan, its high speed trains would run from Liverpool to London but would first need to traverse almost 40 miles of Victorian railways at slower speeds before accessing new, gleaming track south of Crewe. The Liverpool service would be limited to the shorter 200m ‘classic compatible’ trains with half the seats and would run two services per hour with a running time to London of one hour and 34 minutes. Meanwhile, Manchester would receive the gold-plated service - three 400m double-length ‘captive’ trains per hour, speeding to the capital in one hour and 8 minutes – three times Liverpool’s capacity and 28% faster – the end of historic parity in connections to the south.

The lack of high-speed infrastructure to serve Liverpool would prevent the release of capacity on our existing local network, which was supposed to be one of the selling points of HS2. This would severely limit the development of new passenger and freight services and ran contrary to the recommendations of ‘Rebalancing Britain: Policy or Slogan?’ – the Heseltine / Leahy report of 2011 which stated:

‘Government should amend the currently proposed High Speed 2 route, so it connects to both Manchester and Liverpool directly. In the same time frame and to the same standard, Government should commit to assuring Liverpool’s historic parity with Manchester for travel time to London and thereby avoid harmful competitive disadvantage to Liverpool in attracting inward investment’.

That harmful competitive disadvantage was confirmed by accounting giants KPMG who produced their report – HS2 Regional Economic Impacts on behalf of HS2 in 2013. It showed maps of Britain covered in big green circles, where HS2 would uplift the economy of cities and towns. There were, however, little red circles and they were less good news and one of them was over Liverpool. To be fair, the report claimed Liverpool’s GDP could be uplifted by 1.2% in ‘favourable’ conditions, but equally it could shrink by 0.5% in ‘unfavourable’ ones. Not exactly a ringing endorsement and a worse outcome than for towns and cities that were not even connected to the network in any way, such as Hull.

In response to this threat, a coalition of academics and local business figures led by Andrew Morris banded together to form 20 Miles More, an independent campaign group lobbying for a direct, dedicated link to HS2. The 20 miles referenced in the name referred to the length of the shortest link to the HS2 network. Our group, of which I was a director, produced reports, met with political, business and transport leaders and responded to consultations. The assistance of political consultants Jon Egan and Phillip Blond helped us to secure television coverage for our launch event.

Something must have stirred because not long after the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority and the local councils woke up to the danger and launched their own campaign called Linking Liverpool and we’d like to think we had something to do with that. They calculated that a direct Liverpool link to HS2 would be worth £15 billion to the local economy and secure 20,000 new jobs. At last, the issue facing our city was being taken seriously.

“That harmful competitive disadvantage was confirmed by accounting giants KPMG. Their report showed maps of Britain covered in big green circles, where HS2 would uplift the economy of cities and towns. There were, however, little red circles and they were less good news and one of them was over Liverpool.”

One point that we made in our report was that a Liverpool link to HS2 could form part of a new rail link to Manchester and over the Pennines to Leeds. We felt vindicated when the Northern Powerhouse Rail initiative was launched in 2014. This envisaged six northern cities – Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Hull, Sheffield and Newcastle being linked by new high speed rail infrastructure. This resonated with Boris Johnson’s ‘Levelling up’ agenda.

In 2020, construction work on the first phase of HS2 (London to Birmingham) started and the realities began to strike home. The prospect of miles of countryside being torn up for a new railway generated local opposition and the wrath of environmental groups, especially in the home counties, but it was the rapidly escalating cost of the project that really concentrated minds. An initial 2010 estimate of £33 billion had now ballooned to £71 billion with some commentators suggesting the final figure could be well over £100 billion.

Why costs spiralled out of control may be down to a number of reasons – overspecification of the initial project, inflation, procurement issues, planning delays, environmental mitigation, and of course, government interference. The result was cutbacks and delays, culminating in Rishi Sunak’s announcement at the Tory’s Manchester Conference – bad news for ‘the north’ delivered in the self-declared heart of ‘the north’, eyeball to eyeball.

Figure 1

Routes and phasing of HS2 as they stand following Sunak’s recent announcement.

Looking at the map, what Sunak has done is to prune HS2 back to Phase 1, which runs from London to Birmingham. Gone is Phase 2a from Birmingham to Crewe, Phase 2b (East) from Birmingham to East Midlands Parkway and Phase 2b (West) from Crewe to Manchester. What has been retained is the link from London Euston to Old Oak Common (reportedly now subject to finding private sector investment) – vital for delivering an effective HS2 service – as well as the link at Lichfield (Handsacre) junction to the existing West Coast Main Line, which allows trains from Liverpool and Manchester to make use of HS2.

The implications for the North West are significant and on the upside, the damaging inequality between Liverpool and Manchester identified by Heseltine and Leahy has been removed. So, from the completion of Phase One (currently scheduled for some time between 2029 and 2033), both Liverpool and Manchester will have services to London making use of existing tracks as far as Lichfield. Trains will run on HS2 for over 60% of the distance from London to the North West with the remainder of the journey on the much slower classic network. That will give a journey time to Liverpool of around one hour and 46 minutes and to Manchester of one hour and 41 minutes. This five-minute difference contrasts with the 26-minute difference that would have occurred had Phase 2b gone ahead. Liverpool’s train capacity will be unaffected, remaining at two 200m long units per hour (each carrying up to 550 passengers) - whereas Manchester will see a halving of its promised capacity to three 200m units. This is because the 400m long, 1100 passenger ‘captive’ trains (trains that can only run on the new HS2 route) that were to serve Manchester under the original plans can no longer do so.

“It is difficult to support a proposal that would deliver so little to our city and so much to a city that is an economic rival.”

The reduction in overall train capacity and increase in journey time is, of course, a body blow to the North West and has resulted in accusations of betrayal in certain quarters. But while the avoidance of baked-in disadvantage between our two cities might provoke a sigh of relief in some, it would be wrong to assume that what is bad for Manchester must be good for Liverpool. As Jon Egan pointed out in his recent Liverpolitan article, Mancpool: One Mayor, One Authority, One Vision, the real disparity is not so much between Liverpool and Manchester but between the two cities and London. However, it is difficult to support a proposal that would deliver so little to our city and so much to a city that is an economic rival.

Rethinking Northern Powerhouse Rail

Another victim of the latest cuts is Northern Powerhouse Rail. This body is to be replaced by a new entity known as Network North and improved journey times are promised from Manchester to Bradford, Sheffield and Hull with £12 billion allocated to a link between Manchester and Liverpool. How that money is to be spent will be the subject of agreement between our civic leaders (and presumably other North West towns such as Warrington).

Northern Powerhouse Rail envisaged high speed lines linking the main cities of the North West. However, when the Department of Transport published the Integrated Rail Plan (IRP) in 2021, these aspirations were somewhat diluted.

Figure 2:

The Integrated Rail Plan (2021) - not so integrated now

“What does all this mean for that ring-fenced £12bn route between Liverpool and Manchester? Will there still be a requirement for the Manchester Airport tunnel? Budgeted around the £5bn mark (before inflation hit) that would take a hefty chunk out of the available cash.”

According to the IRP plan, the Liverpool to Manchester rail route would be achieved by a mixture of upgraded freight and passenger lines, some new construction and the Manchester branch of HS2.

This arrangement was never optimum – being seen as a ‘bolt-on extra’ to HS2. However, it did directly connect Liverpool to the new rail network allowing a London connection to HS2 via Tatton Junction.

Changes were made to the IRP routing following the publication of Sir Peter Hendy’s Union Connectivity Review in November 2021. Hendy identified that the best way of increasing passenger and freight capacity to Scotland and Northern Ireland (via the Port of Liverpool) was by upgrading the existing West Coast Main Line north of Crewe.

The proposed route of HS2 to the North – the ‘Golborne Spur’ to the east of Warrington - was subsequently deleted and a review put in place to determine an alternative route that better met the aspirations of the Hendy report. This is, for now, clearly off the agenda.

So, what does all this mean for that ring-fenced £12bn route between our cities? Will it stay the same or once again morph into something else? Certainly, this is an opportunity to completely rethink the Liverpool to Manchester link. For example, will there still be a requirement for the Manchester Airport tunnel? If so, budgeted around the £5bn mark (before inflation hit) that would take a hefty chunk out of the available cash – although it is difficult to see how else a new link can be run into central Manchester. However, given that there is no longer a need to accommodate HS2, strictly speaking there’s no reason why an improved alignment can’t be sought. But there may be other ways to spend the money.

A Mersey Crossrail?

Prime Minister Sunak has promised that the £36 billion ‘saved’ by the cancellation of HS2 Phase 2 will be re-invested in a plethora of new transport projects. Mention has been made of electrifying the North Wales main line, extending the Midland Metro, a host of road projects and finally giving Leeds its long-promised metro. Given that the cancellation means that we in Liverpool will now suffer from reduced journey time to the capital, let’s hope that a reasonable slice of that money comes to our city.

Liverpool has a developed transport network thanks to the infrastructure work of the 1970s, which gave us the Merseyrail system. However, one problem with the network is its limited coverage. The frequent electric trains running underground in the city centre only serve the Wirral, Sefton, a narrow strip of north, south and central Liverpool (but not the east) and a small part of Knowsley. That is a result of a failure to complete the original project following funding constraints in the mid-70s.

Now, we have the chance to complete that project – something that would give the Liverpool City Region a comprehensive rapid transit system second to none in the UK outside the capital.

I’m going to call it Mersey Crossrail because it would truly open up transit from north to south and east to west. It would make possible near seamless travel not only within Liverpool but also to the important network of satellite towns around and beyond the city region. The access to new job and lifestyle opportunities that would arise would be transformative for our people, while also encouraging modal shift to greener forms of transport. How much would this work cost? Probably in the region of £1 billion, which is a fraction of the cost of constructing a similar system in another city. That is because so much of the system is already in place.

So, what would this project entail? Apologies in advance because I’m now going to get into the nuts and bolts. I can’t help myself, I’m a rail enthusiast.

“Mersey Crossrail would make possible near seamless travel not only within Liverpool but also to the important network of satellite towns around and beyond the city region.”

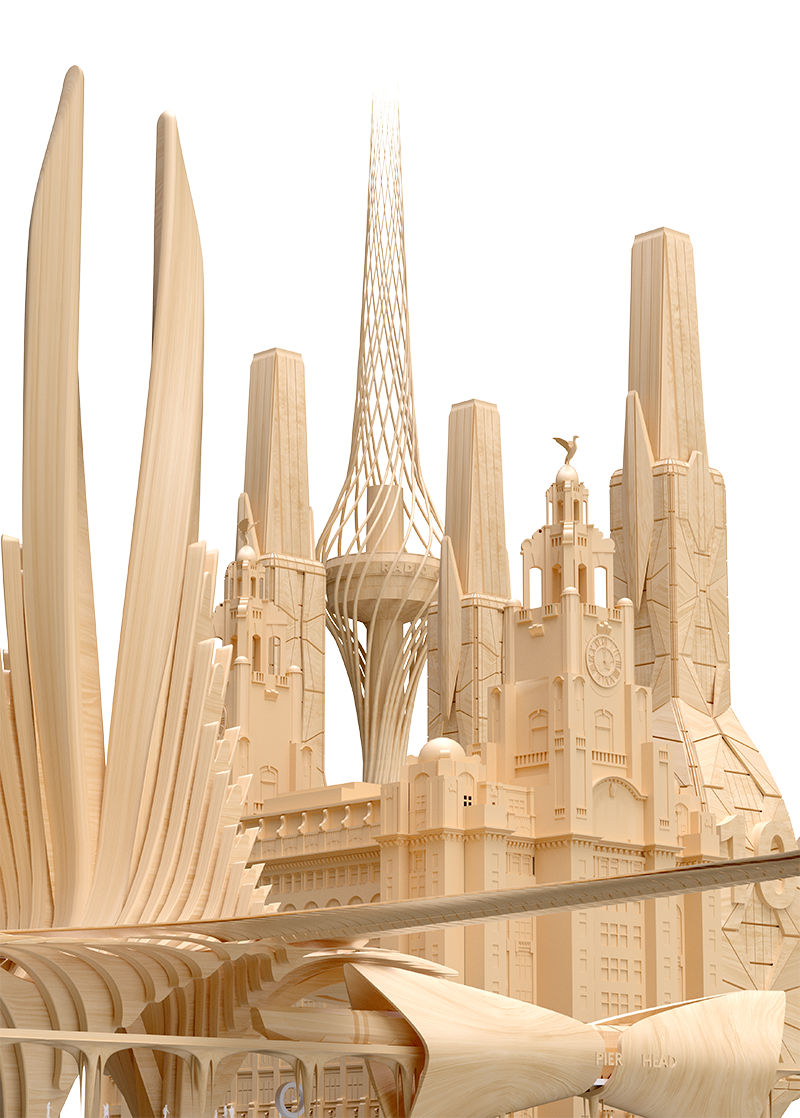

Imagined, new Liverpool Central Station at the heart of an expanded Merseyrail network. Images by: mmcdstudio.

A 4-Step Transport Plan for Liverpool - Features and Benefits

Step 1. Expand Liverpool Central Station

First up, an expansion of Liverpool Central station, which currently hosts Northern Line services to Southport, Ormskirk, Kirkby and Hunts Cross. The station suffers from overcrowding due to its cramped island platform and the need for enlargement has long been recognised.. Widening the station envelope would not only improve the passenger experience, it would also unlock the next stage of transport expansion.

Step 2. Unlock the network by building the ‘Edge Hill Spur’

A new tunnel would be constructed from the south end of the station to Edge Hill connecting to the disused Wapping Tunnel which dates from the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830. This proposal was formerly known as ‘The Edge Hill Spur’ and is the key to unlocking the true potential of the Merseyrail network because trains would now be able to run seamlessly east to west underneath the city streets in part by using old, mothballed underground tunnels. This Edge Hill link would effectively form a Mersey Crossrail with the prospect of services running between towns such as St Helens and West Kirby. Construction would involve minimal disruption to existing services thanks to header tunnels constructed back in the ‘70s.

The benefits of such a scheme are immense. Merseyrail would be cheaper to run because transiting through the city instead of terminating makes more economical use of trains and train crews, potentially increasing train frequency. However, it’s the expanded travel opportunities that would be the major plus.

Every station on Merseyrail would be within a maximum of one change of every other one. For example, City Line passengers would have direct access to Liverpool Central and Moorfields with their retail and employment opportunities or could run through to other destinations such as Birkenhead, Chester, Bootle or Southport.

“Every station on Merseyrail would be within a maximum of one change of every other one.”

Step 3. A new underground station for the Knowledge Quarter

One proposal that’s never made it off the drawing board is an underground station near to the university on Catherine Street serving the Hope / Myrtle Street area. Build the Mersey Crossrail and this could become a realistic option, not only adding important services for our legion of students and academics but also a much-needed shot in the arm for the broader Knowledge Quarter, including the strategically important Paddington Village area with its growing medical biotech cluster.

Step 4. Create new Merseyrail branches to the wider city region and beyond

With the partial reconstruction of a former flyover at Edge Hill, City Line services could link Runcorn to St Helens and Newton-le-Willows. This would add three more branches to the Merseyrail network covering a broader sweep of Liverpool, Knowsley, St Helens and Halton. Services could even be extended beyond the City Region boundary to Wigan, Manchester and Crewe thanks to the Northern Hub electrification schemes of the last decade and the introduction of the new fleet of Merseyrail trains with their dual voltage capability.

Another opportunity, which is already in progress, and which would benefit from additional funding, is the extension of the existing Merseyrail network using battery technology. We can now see this technology in operation with the opening of the new Kirkby Headbolt Lane station. This is served by trains running off the electrified network from the existing terminus at Kirkby. Future proposed destinations include Preston via Ormskirk, Warrington Bank Quay via Helsby, Wigan Walgate via Kirkby and, possibly the complete length of the ‘Borderlands’ Line from Bidston as far as Wrexham.

One great benefit of battery extensions, apart from avoiding the cost of extending electrification, is the opportunity to displace existing diesel services (e.g. Kirkby to Wigan, Ormskirk to Preston), so both reducing operating costs and harmful emissions.

Figure 3:

Shows the Merseyrail extensions possible with the Mersey Crossrail scheme. It also shows the existing proposals for battery extensions of the existing Wirral and Northern Lines.

With all of the proposed extensions in place, Merseyrail would become a powerful regional rail network, fully integrated into Liverpool City Centre. It would extend both into North East Wales and Greater Manchester.

It should be noted that, these extensions reflect the level of spending on transport expected for a city region the size of Liverpool, with a population of 1.5 million people. It is by no means extravagant.

The cancellation of Phase 2 of HS2 has been a blow for the North West region. However, the Liverpool City Region missed out on the initial proposals. Now, there is an excellent chance to redraw the rail map of the North West to give a more equitable distribution of the benefits that will still flow from the Phase 1 railway.

We now have a second chance with everything to play for. So, let’s hope that our political leaders take notice and deliver us the transport system that the region so clearly requires.

Martin Sloman is a civil engineer and former railway consultant. He is a director of the ‘20 Miles More’ lobby group, a coalition of academics and local business figures, which campaigned for a direct link from Liverpool to HS2.

What do you think? Let us know.

Add a comment below, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

HS2 - A Liverpool coup?

The Department for Transport has released the ‘Integrated Rail Plan for the North and Midlands’ to much wailing and gnashing of teeth anywhere north of Birmingham. But is it really as bad as all that? What exactly does it mean for the future of the Liverpool City Region and its rail connectivity?

Michael McDonough & Paul Bryan

The Department for Transport has released the ‘Integrated Rail Plan for the North and Midlands’ to much wailing and gnashing of teeth anywhere north of Birmingham. But is it really as bad as all that? What exactly does it mean for the future of the Liverpool City Region and its rail connectivity?

Depending where you live, HS2 (or High Speed 2) has been seen either as a god-send for levelling up or a blight on pristine countryside. It’s been controversial from the start. Some of that has to do with the cost - after all you can buy quite a lot for the, by some estimates £100bn+ price tag. Some of it has to do with a sense of entitlement or environmental catastrophism in the home counties from the Not In My Back Yard brigade. But mostly, it’s the long-running sore of unequal investment, as northerners watch on jealously as one prestige project after another has been signed off around London. ‘When is it our turn?’, we asked and it seemed HS2 and HS3, subsequently christened Northern Powerhouse Rail, was the answer. Of course, Labour’s northern strongholds have long been suspicious, ever watchful for that knife in the back, and who can blame them? Rumours of nips and tucks to the ambitions of northern travellers have circulated for years and now those rumours have been put out of their misery. The eastern leg to Leeds is no more, Manchester is not getting it’s gold-plated underground station, Bradford is off the map and Newcastle, well they were never on it in the first place. But what about Liverpool?

‘The North’ is, and perhaps always was, a convenient ‘catch-all’ phrase used to hide the oh-so-obvious regeneration focus on Manchester.’

Watching the whole HS2 debacle from Liverpool has been something of a frustrating process. From the outset, our leaders have done their level-best impression of an ostrich with it’s head somewhere where the sun doesn’t shine. They never seemed to understand the existential threat that HS2 posed to the city in its ‘Manchester-friendly’ form. Ah, Manchester, that northern capital (self-appointed), who doesn’t dream of being relegated to commuter-town status to serve that inflated mill-town? At Liverpolitan, that’s long been our suspicion, since before we were a twinkle in our self-published eye(s). ‘The North’, is and perhaps always was a convenient ‘catch-all’ phrase used to hide the oh-so-obvious regeneration focus on Manchester and the lack of focus on other places like Liverpool, Bradford and Newcastle. The logic of agglomeration means all roads point east along the M62. Why don’t they just admit it instead of all this secret code stuff?

Which brings us back to the Integrated Rail Plan for the North and Midlands. If it’s true that ‘The North’ is something of a deception to hide the fact that its cities have competing interests, then maybe we should take off the northern hair shirt and look with fresh eyes at the government’s new plan. Forget about the others, what does it mean for Liverpool?

Manchester-centric

Before we tuck too far into that, it’s most probably worth a quick history lesson. The HS2 project was first launched in 2009 by the Labour government and then picked up a year later by the newly elected Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition administration. They quickly began a consultation on a route from London to Birmingham, with a Y-shaped section to Manchester and Leeds. High speed rail was to become one of the centre pieces of then Chancellor George Osbourne’s ‘vision’ for an all-inclusive ‘Northern Powerhouse’ (singular, not plural) viewed through the skewed lens of his Tatton, Cheshire constituency.

The resulting report and general direction of travel made it immediately clear that this mammoth piece of railway infrastructure was going to serve up yet another Manchester-centric political indulgence. The scales would be tipped conclusively in favour of ‘regional capitals’ such as Manchester and Leeds, relegating cities such as Liverpool and Sheffield to more tertiary positions. Liverpool’s obvious absence from visuals, media coverage and general debate around the HS2 project only seemed to re-enforce this essentially political idea. For some, it may have entrenched notions of ‘managed decline’ by an uncaring Conservative government but our Liverpool leaders didn’t seem to notice. Look trains! Trains good…

At the time, there were numerous debates and disputes around the data on rail capacity, BCR (benefits-cost ratio) and route alignments, all used to justify a heavy public investment on the Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds sections of the line. Train-spotter types got all exercised about it. There seemed to be some logical perversion going on. Liverpool it was argued, didn’t need more trains to London because there wasn’t enough passenger demand, but Leeds did need more trains because, well, they needed to stimulate more demand from the current low levels. Say what? It was like one of those National Lottery games where the outcome was already determined and you only had the illusion of choice. The data was made to fit the argument as far as the Liverpool City Region was concerned. Led by Transport Minister Lord Andrew Adonis, the plan for HS2 would leave Liverpool staring down the barrel of a future in which the struggle to stay economically competitive just got a little harder. The dice, it seemed, were stacked.

From the beginning Liverpool’s politicians didn’t seem on the ball. Even ones with a bit of clout weren’t really arguing Liverpool’s case. Maria Eagle (former Shadow Transport Minister) and Louise Ellman (Transport Select Committee) were strangely absent from the debate despite holding roles that would have helped give Liverpool a voice. It was only after the establishment of 20 Miles More, a campaigning lobby group which made the case for better Liverpool HS2 connections, that the city region’s leaders finally started to understand the peril and by then it was very much an uphill struggle. Our politicians had like Emperor Nero fiddled while Rome burned (according to legend).

Prioritising Planes

Meanwhile, to the east our friends in Greater Manchester had hit the jackpot, although it must be said, that forward-thinking and a pragmatic attitude to working with Conservative governments had certainly played their role. The HS2 alignment was to track away from Liverpool with its 1.6m inhabitants to serve a dedicated Manchester Airport station (and its Cheshire hinterlands) on the main trunk line. This gold plated promise, which would punishingly add to journey times between Liverpool and London came courtesy of a vague commitment to make a local ‘contribution’ to costs and a Chancellor whose own constituency sits perhaps coincidentally on the south western fringe of the city. Naturally, Manchester was also awarded with a further £7bn tunnel bored all the way to the city centre to meet a new station alongside Manchester Piccadilly.

In short, from the start HS2 pushed Liverpool to the periphery. The city region would be served by a slow lane connection using old tracks and with no promise of additional capacity. While Manchester and Leeds were drawing up plans for regenerated business quarters and glamorous city-pads off the back of huge station investments, some evidence pointed to the project causing a net loss in GVA (Gross Value Added) for the Liverpool City Region. No investment, no seat at the table and notably, no meaningful support from ‘The North’ to help Liverpool to benefit. That’s northern solidarity in action. Politician, Andy Burnham likes to speak for ‘the North’ but invariably only one city seems to benefit from his political manoeuvring.

It begs the question, whether Liverpool should de-couple itself from the pan-northern view that the government transport plans are a disaster. If the old plans weren’t so good for us, maybe the new plans are better? It is clear that Manchester and Leeds stood to gain the most from HS2 as previously defined. Now that the eastern leg of HS2 to Leeds has been entirely removed, maybe the focus of the benefits have moved a little closer to home.

Liverpool should take a more pragmatic view when assessing this change of direction and put the interests of our city first.

The Government’s New Plans

The first thing to say is that as far as the new Integrated Rail Plan is concerned, it’s a case of swings and roundabouts. Liverpool gains in some areas and loses in others. For HS2, things are looking much rosier, whereas the never fully committed to and still very much a paper project, Northern Powerhouse Rail has been downgraded. But one thing is clear. It is simply untrue to say, as Metro Mayor Steve Rotheram did, that the government have “chosen not to deliver anything at all.”

So let’s look at HS2. What the government is now proposing for Liverpool brings fast tracks much closer to the city. It’s better late than never ambitions to have a dedicated spur from the main route, while in no way fully delivered, have taken a major step forward. The argument that Liverpool is important enough to receive a better service appears after a long and bloody battle and against all the odds to have been won. Whereas before, Liverpool’s connection to the new rail network was situated some 40 miles away, just south of Crewe, under the latest proposal HS2 tracks will now run to Ditton Junction, approximately 11 miles distant and right on the outskirts of the city. This resolves one of the two main capacity constraints facing our part of the network and substantially increases the scope for an expansion of freight services - a key strategic goal for the growth of Liverpool’s port. It will achieve this by relieving the congested section of the West Coast Mainline (WCML) between Crewe and Weaver Junction (where the Liverpool branch connects) allowing many more freight paths towards the Midlands and the South. As an added bonus the revised route will also reduce journey times to London for passengers although by only a modest 2 minutes.

Those improvements will be achieved through a combination of new track linking Manchester to Warrington Bank Quay station and the use of the under-utlised Fiddler’s Ferry route which will be redeveloped and electrified (without a significant effect on existing passenger services).

Of course, what we all want is for new track to be laid all the way to central Liverpool serviced by a station with sufficient capacity to handle the additional services, as was discussed in Martin Sloman’s article, Lime Street or Bust? The options for Liverpool’s HS2 station. But we should point out in the interests of fairness, that a new station and new dedicated track is not and never has been on offer from the government; it’s just something we feel the city needs. To go those extra eleven miles and build a new station would, according to the report, require local funding. This is, of course, a ludicrous and hypocritical position for a national government to take (given the resources thrown at other cities) but there’s room for optimism. A future government may take a different view and once the engineers start to tuck into the final details and look at the numbers, the business case for raising ambitions further may become obvious. After all, the big argument for better Liverpool services has been won.

In the meantime, the rail plan proposes a solution to the second big capacity constraint facing Liverpool - the narrow throat that is the entrance to Lime Street Station. This acts as a significant break on the amount of trains that can come in and out of the station at any one time, producing that all too familiar Victorian-era crawl over the last mile. The report recognises this issue and proposes that development work should focus on altering Lime Street and its approaches. Intriguingly, it states that ‘Network Rail analysis also shows that Liverpool Lime Street station can be altered largely within the boundary of existing railway land to accommodate the proposed service levels resulting from HS2 and NPR.’ Further work, it says, is needed to confirm the precise scope of interventions. This clearly points towards a very significant re-modelling project for our station.

For too long Liverpool’s interests have been subsumed under a ‘Northwesternist’ agenda centred politically and economically on the needs of Manchester. It has been the failing of our local parties - all of them - Labour, Liberal, Conservatives and Greens to notice what has been going on.

If we move into the albeit not entirely reliable realms of speculation, the acceptance of the requirement to address Lime Street’s capacity constraints may open up a chink of light for the long overdue Edge Hill Spur, a project originally proposed in the 1970s. This would connect Liverpool Central station with the east of the city via the currently abandoned Wapping Tunnel to Edge Hill. If given the green light, local services could be moved out of Lime Street allowing it to concentrate on longer distance services. It would also precipitate the wholesale redevelopment of Central Station with all the benefits that would entail. We’re not saying it’s going to happen. Just that if you follow the logic of the report, it kind of makes sense.

Runcorn appears to be the big loser in this new plan, as it will no longer be on the HS2 map. But all is not lost for south Liverpool. A new station at Ditton Junction would serve the same market equally well and has to be an option as the detail of the plans are worked through. It is also not beyond the bounds of possibility that an expanded Lime Street could support a London-Runcorn service on the old WCML or provide a connection at Crewe.

One of the not really spoken about benefits of the new plan is that Liverpool’s new connections should now open at the same time as HS2 Phase 2B to Manchester. In an age when Liverpool must learn to compete with its northwest city brother in every field, this is an important win. Comparative journey time penalties to London will impact on our attractiveness to investors and although we do concede a 21-minute longer travel time, it would have been worse and in place for longer under the old plan. Marginal gains can add up.

As for Northern Powerhouse Rail, it’s hard to argue that we are now on anything but thinner gruel. Travel times to Manchester will not improve appreciably from the current levels offered to Victoria Station, and the Piccadilly route will be 6 minutes slower than was previously proposed. Trips between Liverpool-Leeds will also be slower, downgraded from 61 minutes to 73, although still significantly faster than the 106 minutes we experience today. Either way, as most people don’t like to commute for substantially more than one hour and tend to live in suburbs, not train stations, it’s never been truly convincing to believe that significant numbers would commute between the two cities of Liverpool and Leeds anyway. Nevertheless, in the cold light of day, NPR may not be what we dreamed of, but it’s still a significant step up from what we suffer in the present.

So despite the generally negative tone from media commentators and local politicians (who will be driven by their own political imperatives), the proposals carry with them some very sensible ideas. If implemented, the rail plan will mean the Liverpool City region benefits from:

New infrastructure for both HS2 and Northern Powerhouse Rail services

Improved capacity, journey times, frequencies and connectivity

Facilities will now open simultaneously with Phase 2B to Manchester

Andrew Morris of 20 Miles More told us, “The journalistic hype is quite different from the reality. My reading of the new plan is that, although imperfect, it’s a coup for Liverpool. Since the 20 Miles More campaign, the Liverpool City Region has raised its ambitions and engaged constructively with HM Government. The LCR has been unified and managed to navigate through the political quagmire the Department for Transport created when it threw in together all of the northern centres stakeholders. Yorkshire has lost out due to a lack of unity.”

It’s hard to square the comments of Andrew, who has been living and breathing train services for decades with those of Steve Rotherham, our Metro Mayor. He said, “Northern Powerhouse Rail had the chance to be transformational for our area and the wider north and important for the UK on the whole. But many voices including my own said they were going to deliver transformation on the cheap. Instead they’ve chosen not to deliver anything at all. We were promised Grand Designs, but we’ve had to settle for 60 Minute Make Over.”

The Manchester to Liverpool section of Northern Powerhouse Rail has been prioritised ahead of Manchester to Leeds. For Leeds and Bradford, that’s not good. But for Liverpool, well we should be OK with that. This is where we should have been from the beginning, because the Liverpool-Manchester axis has greater economic potential than the Manchester-Leeds one.

For too long Liverpool’s interests have been subsumed under a ‘Northwesternist’ agenda centred politically and economically on the needs of Manchester. It has been the failing of our local parties - all of them - Labour, Liberal, Conservatives and Greens to notice what has been going on. Instead, they were too busy picking their own small-time fights while competitor cities manoeuvred to advantage around us. Perhaps if our politicians adopted a more pragmatic approach to working with central government, whatever it’s political hue, we might not have needed campaigns like 20 Miles More in the first place.

As you wade through the interminable list of articles about the disaster that is the new Integrated Rail Plan, think on this… is it possible that most commentators are operating under a logical fallacy? That they have swallowed whole the idea that ‘The North’ is a single identity with common interests and that loss to one is loss to all? If we are being brutally honest, Liverpool may actually benefit competitively in a world where Leeds is a little more hobbled and where Manchester is not so dominant. It shouldn’t be a heresy to say so. Our brethren have been thinking exactly the same way behind closed doors for years. It’s time Liverpool joined the party.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and a Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach.