Recent features

Not So Red: Labour’s Slow Rise in the Scouse Republic

Liverpool wasn't always the ultimate Labour stronghold. For much of the past century, Conservatives have dominated local and parliamentary elections. Historian of the Left, David Swift, charts Labour's surprisingly slow rise to power in not-so-red Liverpool.

David Swift

You don’t often see Liverpool compared to Iran. And certainly a stroll through the city centre on a Friday or Saturday night brings sights you probably wouldn’t see in downtown Tehran.

In an essay comparing the politics of Iran and Egypt, the sociologist Asef Bayat pointed out that Egypt, despite having strong popular support for Islamist politics and a weak middle class, never established a religious theocracy along Iranian lines. The difference being that in Iran, the government of the Shah had successfully eliminated all secular opposition – liberals, socialists, trade unionists – so the Mullahs were the only people in a position to take over, despite a lack of broader support for their project. So Egypt had an Islamic movement but not an Islamic revolution, and Iran had an Islamic revolution without much of an Islamist movement.

Over the past 100 years something similar has happened in the political transformation of Liverpool. From a bastion of working-class Toryism, Liverpool has become a city with the five safest Labour seats in the country. Other areas with similar demographics have seen Labour’s support slide in recent years, but in Liverpool the party’s dominance has continued to grow.

Yet curiously, beneath the surface, just like in Iran, the dominant political movement has been anything but strong. Liverpool has undergone this Labour revolution with a much weaker, organised Labour movement than other cities. Don’t believe me? Look at the history.

This year marks the centenary of the election of Jack Hayes, the first Labour MP to sit for a Liverpool constituency – who won the 1923 Edge Hill by-election. This breakthrough came roughly two decades after other ‘Labour heartlands’ such as Manchester, East London, Glasgow, Leeds and South Wales had elected their first Labour MPs.

Before and even after Jack Hayes’ triumph, Liverpool was solidly Tory. From 1885 to 1923, with just a few exceptions, the city’s nine constituencies were won by the Conservative candidate in every parliamentary election. Toxteth was represented by people with little claim to working class roots; people with grand-sounding names such as Henry de Worms and Augustus Frederick Warr. It is hard to imagine now but for 14 years the MP for rugged Kirkdale was a Baronet called Sir John de Fonblanque Pennefather.

The most notable exception to Tory dominance at that time was the Liverpool Scotland constituency, centred on Scotland Road, which was dominated by Irish immigrants. Held by the Irish Nationalist T.P. O’Connor from 1885 until his death in 1929, his victory remains the only time a British parliamentary seat has been won by an Irish nationalist party outside the island of Ireland.

Of course, the Liberals had the occasional reason to celebrate too, winning Liverpool Exchange in 1886, 1887, 1906 and 1910 as well as Liverpool Abercromby in their general election landslide of 1906. But even at that election – a wipeout for the Tories and their worst result until 1945 – the Liberal Party only managed to win two of Liverpool’s nine seats, with the Conservatives taking six out of the other seven.

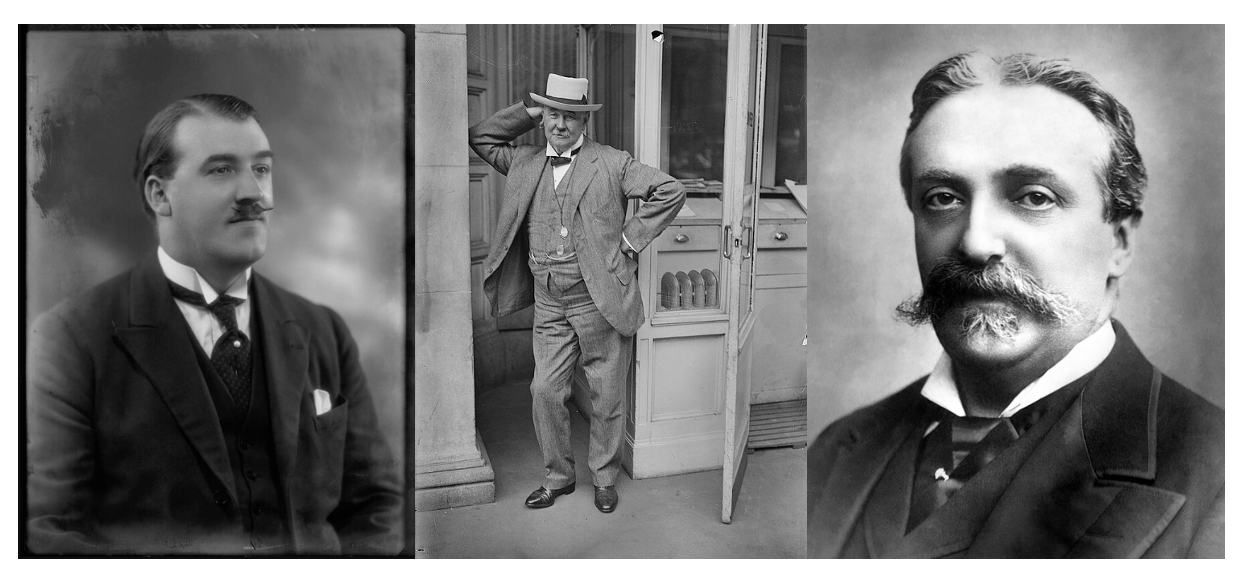

An Irish Republican, Tory Baron and Liverpool’s first Labour MP walk into a bar. But who’s who?

Left to Right: Jack Hayes Labour MP for Edge Hill (1923-31); T.P. O’Connor the Irish Nationalist MP For Liverpool Scotland (1885-1929); and Baron Henry de Worms, Conservative MP for East Toxteth (1885-95). Image credits in respective order (left to right): Bassano Ltd, public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Bain - Library of Congress (1917); Alamy

Some commentators have claimed Liverpool politics are based on rebelliousness or innate defiance and a willingness to speak up and go against the crowd. Which makes what happened in the 1906 general election all the more fascinating. Dominated by the issue of free trade, the Conservatives lost badly at the national level because it was feared their plan to impose tariffs on imported goods would damage trade. And yet even in this election, in a town as totally dependent on trade as Liverpool, even in a port city, Liverpolitans put two fingers up to the national trend and voted for the Tories anyway. Was this an early example of that noted tendency to contrarian defiance or slavish support for the party of power?

Of course, at this time, the six-year-old Labour party was not a serious force around the banks of the Mersey and their leader Ramsay MacDonald – who later become the first Labour Prime Minister, knew it too. In 1910, after a visit to the city he seemed to accept they had no prospects of winning there any time soon, writing with a note of sour grapes that ‘Liverpool is rotten and we had better recognize it’.

Why was Liverpool so slow to support the party of the working class?

One explanation often put forward is the narrowness of the parliamentary franchise which dictated who got to vote. It’s claimed voting restrictions prevented many working people from making their voices heard and it’s certainly true that this affected politics at this time, though perhaps not always in the ways most commonly understood. From 1867, men in ‘borough’ constituencies (usually towns and cities like Liverpool) were able to vote in general elections but only if they were defined as a ‘householder’. This meant a man living independently by himself or with his wife and children who also paid a minimum of £10 a year in rent. In theory, most working-class men could now vote, but in reality it’s estimated 40% of men nationwide were disenfranchised until these rules were relaxed in 1918.

This was because the lack of affordable accommodation meant many men still lived at home with their parents or in houses with multiple families, and so fell foul of the rule. In a port city like Liverpool, where seafaring was the second largest source of employment, this would have been particularly significant because so many men worked away for long periods. The 1921 census found there were twelve times as many men without a fixed address or workplace in Bootle than in St Helens.

Nonetheless, some historians have challenged the idea the franchise disproportionately affected working-class voters, noting that, on average, men from working-class backgrounds found work, left home and started families earlier than their middle-class equivalents. As noted by Neal Blewett in an article for Past and Present, middle-class professionals were more likely to be lodgers, who very often couldn’t vote. It’s too easy to use the disenfranchisement of working-class voters to explain Tory dominance in the city - especially since women, who have tended to favour the Conservatives by wide margins, were unable to vote in general elections until 1918. Perhaps the limitations on the voting franchise hurt rather than helped the Tories. In her influential book, The Iron Ladies (1987), journalist Beatrix Campbell claimed Labour would have won every election between 1945 and 1979 but for women’s right to vote.

The influence of sectarianism overstated

It’s also too easy to blame ‘sectarianism’ for Tory rule in Liverpool. According to this analysis, conflict between Protestants and Catholics divided the working class vote, with Catholics favouring ‘home rule’ for Ireland supporting the Irish Nationalist party (the IPP), while Protestants opposing greater Irish autonomy voted for the Conservatives. The argument goes that the conditions for a Labour breakthrough in Liverpool only occurred after Irish independence in 1922, when the sting went out of the nationalist cause. Catholic votes transferred to Labour, whilst Protestants, with the nationalist issue seemingly resolved, felt less inclined to vote Tory.

But many historians, such as Sam Davies, have downplayed the importance of sectarianism, arguing instead that Tory dominance resulted from the weakness of the Labour party in local politics and splits in the anti-Tory vote.

Famously, Churchill sent gunboats on the Mersey in 1911 to quell a dockers strike, but despite this Liverpool was still voting Conservative. Meanwhile in Glasgow … Red Clydeside was already represented in parliament. Image: HMS Antrim, Ernest Hopkins, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s instructive to compare the political situation in Liverpool to that of Glasgow - another town with a violent sectarian divide. While Liverpool outside of Scotland Road was staunchly Tory, in Glasgow, sectarian sentiment saw a surge in support for the Liberal Party. As far back as 1886, with the Liberal Government led by William Gladstone (a Liverpolitan), proposing Home Rule for Ireland under a less centralised United Kingdom, Catholic voters jumped at the opportunity to get behind the Bill. Nationally, the 1886 general election saw the Liberals lose over 150 seats as the issue proved unpopular. Yet in Glasgow, the Liberals won four of the city’s nine seats – with another two going to the ‘Liberal Unionists’ who, opposing the move, were no doubt supported by the city’s Protestants. Liverpool never saw anything like this degree of sectarian influence.

Back to that 1906 election, which by the way was only the second to be contested by the newly-formed Labour party. While Liverpool was busy voting Tory, in Glasgow, former shipyard worker George Barnes was elected as a Labour MP for Glasgow Blackfriars and Hutchesontown, a seat he held until he was elected for the new Gorbals constituency in 1918, alongside Neil Maclean, who won in Govan. By 1922, Labour was winning ten of the city’s 15 seats. In contrast, no Liverpool constituency elected a Labour MP until after the party had taken most of the seats in Glasgow.

“It is perhaps forgotten today, but back in the interwar years, the largest unions on Merseyside, the TGWU and the National Union of Seamen - representing dockers and sailors – had an inconsistent relationship with the Labour party.”

The importance of skilled workers and Nonconformists

One reason for Labour’s earlier breakthrough in Glasgow was its stronger concentration of skilled trades. Although like Liverpool, a major port, Glasgow relied less on distribution and more on the dominant industry of shipbuilding. This provided a stronger industrial base with many skilled jobs defended by well-organised trade unions. Even if we include the Cammel Laird shipyards in nearby Birkenhead, Liverpool never had a similar level of manufacturing jobs. There was far too much reliance on low-skilled, casual labour which was a lower priority for the wider trade union movement.

At this time, areas that voted Labour had either strong trade unions, or high levels of Nonconformist Protestants such as Baptists, Methodists, Quakers – or both. You can see this trend in places like South Wales, West Yorkshire, East Lancashire, and the Durham coalfield. Nonconformity was linked with moral and political liberalism: Nonconformists such as William Wilberforce had been prominent anti-slavery advocates, and were over-represented among critics of British imperialism. They also challenged elements of the British establishment such as the Church of England and the House of Lords. In Liverpool, however, the trade unions were small or weak, whilst most people were Catholics or Anglicans, with few Protestant Nonconformists.

It is perhaps forgotten today, but back in the interwar years, the largest unions on Merseyside, the TGWU and the National Union of Seamen - representing dockers and sailors – had an inconsistent relationship with the Labour party. In 1927, the Executive Committee of the Liverpool Labour Party (then known as the Liverpool Trades Council and Labour Party) was formed from clerks, postal workers, electricians, engineers, railwaymen, painters and insurance workers. Dressmakers, shop assistants, clerical workers, tailors and garment workers were all well represented in the membership – but representatives from the two dominant occupations in the city were conspicuous by their absence.

Tories still strong after World War 2 and the politics of normal

Even after the 1945 Labour landslide, the Conservatives continued to win elections in Liverpool. Tory MPs were elected for Walton and West Derby until 1964, and for Wavertree and Garston until 1983. At the 1959 local elections, six of Liverpool’s nine council wards were controlled by the Conservatives, and three of those were solidly working-class areas, including Toxteth and Walton.

During the 1970s, control of the council swung between the Tories and Liberals. When the Trotskyist Militant Tendency took over in 1983, they succeeded a Conservative-Liberal coalition.

When Labour was successful on Merseyside in this period it was not because of a strong local labour movement, but because political sentiment was tracking with the ‘normal’, with the city tending to vote in line with national trends

Speaking to political scientist David Jeffery, who studies electoral politics in Liverpool, he told me that after the Second World War there was a general trend towards the ‘nationalisation of politics’. By this he means that national rather than local issues became key determinants in deciding how to vote. Local politics began to matter a lot less, so the Liverpool vote tracked the national vote share. As elsewhere in the country, the party in power nationally would usually suffer in local elections.

As Jeffery explained, the Tory successes in council elections during the late 1960s were not driven by a surge in support for the Tories, but rather a collapse in the Labour vote due to the growing unpopularity of Harold Wilson’s Labour government in Westminster.

Then in the early 1970s, when Ted Heath’s Conservative government was unpopular, Labour and the Liberals did better in local elections, and in 1998, a year after Tony Blair’s Labour landslide, the Liberal Democrats once again took power of Liverpool City Council.

Prone to takeover – the problem with Labour’s low local membership

Even though there was a real change of the political culture and identity of the city in the 1980s, there was still not much of a labour ‘movement’. One of the reasons Militant was able to take over Liverpool Labour was because the local Labour party branches had relatively few members. They’d become hollowed out and simply didn’t have enough people to buttress against a well-organised and well-motivated sect.

Historically, in areas without strong trade unions there would be relatively few people in the local Labour party – put simply if you were not a union member or close to a union member you were far less likely to get involved with Labour. So once the unions lost their strength and influence from the 1980s onwards, alongside a decline in local government, the traditional working class routes into local politics dried up. Membership of Labour constituency branches (CLPs) in traditional working class areas has been on the slide ever since. As an example, the biggest constituency Labour parties today such as Hornsey and Wood Green in London have over 3,000 members, but one of Liverpool’s largest, Liverpool Walton, claims to have just over one thousand, and that might have been at the height of the Jeremy Corbyn membership surge.

One of the reasons Militant was able to take over Liverpool Labour was because the local Labour party branches had relatively few members. They’d become hollowed out and simply didn’t have enough people to buttress against a well-organised and well-motivated sect.

Just as in the early twentieth century, Liverpool today has a large working-class population, but it doesn’t have much of a labour movement – despite Labour consistently winning elections.

There have been well-supported social justice movements: such as during the dock strike of 1995-1998, the Hillsborough Justice Campaign, and more recently grassroots initiatives such as Fans Supporting Foodbanks. But this hasn’t translated into high membership or engagement with the Labour party itself.

Middle-class activists and the politics of identity

Labour’s membership surged under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn from just 198,000 in 2015 to 564,000 by 2017. But how many of these new members were from traditionally working class communities? Creative Commons C.C.0 1.0 via Wikimedia.

As far back as Tony Blair, commentators have noted how the ‘Islington set’ have become increasingly influential in the politics of the Labour party. People whose personal circumstances had taken them a long way from the traditional Labour voter were now shaping the party’s direction. During Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership in the 2010s, membership of the party grew, but often those new members were not from the traditional voter base. London, by comparison to Liverpool, has far higher levels of middle-class graduates and these are exactly the kind of people who have historically joined political parties. It’s not surprising that in places with more middle class voters, there’s been increased enthusiasm and engagement with Labour. But back in the Labour heartlands, not so much. This relative lack of enthusiasm and political engagement can be seen by comparing the turnouts of the last mayoral races in Liverpool and London: in both cases, everyone knew that the Labour candidate would win, yet in London the turnout was 40%, in Liverpool it barely reached 30%.

In recent years, the Liverpool Left has become more radical on cultural issues such as race and ethnicity - but it’s doubtful whether the city’s population is as liberal as their representatives on these issues.

The website, Electoral Calculus breaks down the demographics and political culture of each of the UK’s 650 constituencies, and ranks them according to their political opinion on economics (Left versus Right), internationalism (Global versus National) and culture (Liberal versus Conservative). It then uses cluster analysis to identify the influence of one of seven ‘Tribes’ in each constituency - including ‘Progressives’, ‘Traditionalists’, ‘Centrists’, ‘Kind Young Capitalists’, ‘Somewheres’, ‘Strong Left’ and ‘Strong Right’. It also estimates how each constituency seat voted in the Brexit referendum, a much finer grain of breakdown than exists in the official statistics.

Let’s take a look at how it assesses Liverpool’s five safest Labour seats:

Liverpool Walton - Traditionalist

27 degrees Left, 3 degrees Globalist and 1 degree Conservative; 52% voted Leave.

Knowsley - Traditionalist

26 degrees Left, 2 degrees Globalist, 2 degrees Conservative; 52% voted Leave.

Bootle - Traditionalist

25 degrees Left, 3 degrees Globalist, 0 degrees Social; 50% voted Leave.

West Derby - Traditionalist

26 degrees Left , 6 degrees Global, 1 degree Liberal; 48% voted Leave.

Liverpool Riverside – Strong Left

21 degrees Left, 29 degrees Globalist and 18 degrees Liberal; 27% voted Leave.

As you can see, the top four constituencies are classed as ‘Traditionalists’, according to the Electoral Calculus formula. The people in these seats have, on average, left-wing economic views but cultural and social views that are centrist or conservative.

Traditionalist Kirkby. Small ‘c’ conservatism may rule when it comes to social and cultural views in many of the region’s Labour constituencies. Image Kirkby High Street (2023) by Paul Bryan

In a recent study into how local identities impact on voting behaviour in the Liverpool City Region, David Jeffery also found that while Liverpool constituencies are in the bottom quarter nationally in terms of pro-monarchy sentiment, they are still more pro than anti-monarchy. He found that only 18% of Liverpudlians feel ‘only Scouse’, just 5 percentage points higher than the 13% who feel ‘only English’, with the rest feeling some mixture of Scouse and English.

What can we read into this?

It appears that despite the victories of the Labour party in parliamentary and local elections, there is a large amount of small ‘c’ socially conservative sentiment in the city. That is why up to three constituencies likely voted Leave, and why UKIP came third in the 2014 local elections – only 969 votes off the Greens in second place. They did especially well in working-class wards such as Club Moor, County, Fazakerley, and Norris Green.

This data suggests there’s a risk of Liverpool Labour overreaching on culture, as happened recently with the Scottish National Party (SNP). Despite Scotland’s population being slightly more sceptical on trans rights than the UK average, the SNP leadership assumed they could push forward with radical gender policies - an approach which led to Kate Forbes, who opposes same-sex marriage, coming within 3,000 votes of winning the party’s leadership election.

Within the past year, the SNP has gone from looking invulnerable to now polling only 1% ahead of Labour. Obviously this has not all been down to overplaying their hand on cultural issues, but nonetheless it’s a salutary warning for Liverpool Labour about the dangers of hubris, and mistaking the transformation in the politics of the city for a transformation in its culture.

In the hundred years since the election of the city’s first Labour MP, Liverpool’s support for Labour appears stronger than ever. But history suggests an unpopular Starmer government and continued chaos at the municipal level could well see the party lose power locally and for the majorities of the city’s MPs to be chipped away. The city’s current loyalty to Labour cannot be taken for granted, either by national politicians looking to Liverpool for lessons, or by local figures who might mistake voting patterns for political and cultural radicalism.

David Swift is a historian and writer specialising in Left wing activism who has written for publications such as the New Statesman, The Times, Tribune and Unherd. He is the author of three books including A Left For Itself; and The Identity Myth.

His latest book, Scouse Republic? A Personal History of Liverpool, will be published in 2024 by the Little, Brown Book Group.

*Main image created on Stable Diffusion.

Why we should stop banging on about Thatcher and the Toxteth Bloody Riots

Journalists arrive in Liverpool to tell the same story over and over again - the city cast as the lead in a Shakespearean morality play, fuelled by righteous anger, touched by tragedy, let down by treachery. Yet is our own obsession with the 1980s feeding the media stereotypes?

Paul Bryan

My personal experience of the 1981 Toxteth Riots existed, as for so many others in Liverpool, solely on television. The nightly news reports showed lines of police officers cowering under shields as youths hurled stones and set light to cars and buildings. I didn’t know why it was happening but I knew it was exciting and so did my friends – as if through some mechanism of the collective unconscious we quickly turned it into a street game, unimaginatively called ‘Toxteth Riots’. The rules were fairly simple. All you had to do was clutch a metal bin lid and defend yourself from rocks and stones hurled somewhat half-heartedly by your mates. The winner was the one who could stick it out for the longest. Writing about this now, I’ve only just realised, we were instinctively putting ourselves in the shoes of the police. They at least seemed understandable. Still, it didn’t hold our attention for long. We got bored of it after two nights.

If only I could say the same about the national media. 41 years later and they’re still using the Toxteth Riots as the go-to framing device for just about any story on Liverpool. Of course, in no way do I mean to belittle the experiences of those who were there, or those who suffered under the social forces that made life more difficult. But for me growing up, the riots always felt like something distant, from some other Liverpool, far off and largely irrelevant. If anything, the Toxteth Riots were a boon – they gave me the chance to meet TV scarecrow, Worzel Gummidge at the International Garden Festival three years later, thanks to the intervention of Michael Heseltine, unofficially crowned the Minister for Merseyside.

I mention this personal story because I’ve noticed a tendency in the media and in political circles to describe Liverpool as a single unit, with a single, monolithic outlook and I find this approach unhealthy and untrue. The Toxteth Riots as history and metaphor have become something of an unquestionable foundation stone in our understanding of Liverpool’s journey. I’m not for one minute doubting their significance, but merely wish to flag that, due to the vicarious nature in which they were experienced by many, the events will never speak to us all in the same way and I think that’s worth acknowledging given the sometimes over-simplified, stripped-down caricature of ‘Scouse’ tales that we are often encouraged to identify with. And if that applies to someone who was alive at the time, you can bet it will apply even more to those who were as yet unborn.

The Toxteth Riots sit as the starting point of a master narrative that is told and retold ad finitum. Typically, it’s a story pitched as one of strife and rebirth – a city on its knees rising phoenix-like from the ashes with the regeneration that followed. Either that or it’s used to evidence our home town’s long history of racial inequality. There are further beats in the story of course and usually they point to ‘basket-case’ – a city that just can’t seem to catch a break or get its house in order. A place that is frankly perplexing. Journalists visiting Liverpool tell the same story, time after time, yet they never tire of it, new facts on the ground serving merely to embellish an already familiar pattern.

It would be easy to point the finger at outsiders here, but this game plays out amongst Liverpool’s inhabitants too and I’ve begun to wonder… does the incessant focus on the 1980s (and we must throw the hate figure that is Margaret Thatcher into the same pot) does the constant repetition serve the city’s best interests? Do these references still yield insight or are they just a reheating of old battles, about as useful to understanding Liverpool today as the Suez crisis is to making sense of Britain’s contemporary approach to foreign policy?

A case in point. This week, the Mayor of Liverpool, Joanne Anderson was interviewed by a journalist from the left-leaning New Statesman magazine, enticed no doubt by the city’s hosting of the Labour Party Conference. Ostensibly about Liverpool’s current political crisis, the article began like this… “In 1981, the violent arrest of a young black man near Granby Street in Toxteth, Liverpool, led to nine days of rioting.”

“Journalists visiting Liverpool tell the same story, time after time, yet they never tire of it, new facts on the ground serving merely to embellish an already familiar pattern.”

What followed was a tick list from the unofficial media guide to Liverpool which we presume is handed out by the NCTJ on journalism graduation day. Margaret Thatcher, ‘managed decline’, European Capital of Culture and the regeneration of the Albert Dock, Derek “Degsy” Hatton and the Militant Tendency, gang warfare and the shootings of young children, now sadly updated with new names. Welcome to Fleet Street’s version of Punxsutawney where we’re all doomed to live the same day, every day. Bill Murray, at least, found a way out. In Liverpool, we’re still looking.

Truth is, the story could have been about anything – crime, the opening of an arts festival, or an important football match and it could have been published anywhere – The Telegraph, The Guardian, The New York Times or Unherd. It doesn’t really matter what the initial prompt is, as long as the story stays the same. Liverpool, the city, is perennially cast as the troubled lead in a Shakespearean morality play, fuelled by righteous anger, touched by tragedy, let down by treachery, now sadly a watchword for – (insert your favoured macro-political, agenda-driven blank here).

Refreshingly, the Mayor was not too impressed with the New Statesman article. On Twitter, Joanne claimed the writer had “focused on a whole load of scouse stereotypes” and accused him of “lazy journalism”. I found myself in agreement so I reached out to the Mayor for further comment, and to my surprise she replied. What she had to say, for a local Labour leader is, I think, important and worth hearing. But you’ll have to wait a while. You see, first I have this theory and it involves turning our attention inwards. It’s the real meat in this piece. For as much as we might want to blame the media, I believe that the press are, in large part, reflecting back what we as a city put out about ourselves.

Sometimes, our own worst enemy

Compare these two statements. The first is by a journalist, Oliver Brown, Chief Sports Writer at the Telegraph, who was writing about Liverpool’s complex relationship with the establishment in light of some fans failing to observe a minute’s silence to mark the death of the Queen.

“Liverpool is a city that feels that it has been shunted to the margins of British society. It is scarcely an unfounded view.”

The second is from Kim Johnson, MP for Liverpool Riverside who was describing her sense of betrayal at Labour Leader, Keir Starmer writing in the Sun in 2021.

“We are the Socialist republic of Liverpool, a city that marches to the beat of a different drum, a resilient city that will always come back fighting. But we have a long memory and will not forget this betrayal by the leader of the Labour Party, in our Labour city.”

Can you spot the similarities? For starters, they are both quite careless in their use of the collective – back to that sense of the monolithic, singular opinion to represent the Liverpool way. But they also both spoke to something else – a powerful sense of grievance baked into the city identity. Kim Johnson’s quote in particular was the perfect crystallisation of a view that has become increasingly noisy in recent years – the idea that Liverpool is ‘Scouse, not English’ – a place apart, waged in a perpetual battle to get a fair deal, coalescing around some sense of the ‘Other’.

A few weeks back, the Liverpool Echo’s Dan Haygarth, in a quite remarkable article, attempted to explain why so many in the city reject national identity. As explanations go it was comprehensive, yet strangely unconvincing, but it was a perfect reflection of what passes for common sense around here. Supposedly, our 19th-century Irish roots had turned us into ‘rebels’ sceptical of authority; our coastal location transformed us into natural internationalists who looked out rather than in; a history of being ‘let down by the establishment’ first by the Thatcher government in the 1980s and then over the Hillsborough disaster had for many ‘broken the city’s relationship with England beyond repair.’ Throw in the generosity of EU European Objective 1 funding followed by savage post-2010 cuts from Westminster, a Brexit vote that went the wrong way and a nasty article in the Spectator under Boris Johnson’s watch and a seemingly irresistible case was made for a city destined to walk alone.

Haygarth’s article concludes – “The phrase 'Scouse, not English' not only encapsulates Liverpool's civic pride and a healthy rebellious spirit, but expresses a feeling that the city has been so often let down by the establishment of this country. It should come as no shock that large swathes of this Labour-voting, outward-looking, and heavily-Irish city do not feel like they have much in common with the rest of England.”

“They also both spoke to something else – a powerful sense of grievance baked into the city identity… a mutual connection made through the collective swallowing of bitter pills… our loudest voices complicit in the forging of our own myth of alienation.”

For me, the sense of our loudest voices being complicit in the forging of our own myth of alienation is palpable and the justifications horribly deterministic. Who here thinks their life choices and personality are determined by people born 200 years ago? Stitching together disparate events, our public figures and opinion-formers are consciously weaving a narrative that seems to share some of the features of an accelerated national story – one encompassing communal loss and betrayal, a unique sense of difference forged through a mythic connection to lands beyond the horizon and an othering from a surrounding horde of distinctly unsympathetic barbarians. But as foundation stories go, it seems to lack many of the positive elements that make nationhood worth having – with little sense of victories past or historic purpose hard won. Today, it’s hard to look back to our past days as the Second City of Empire with any pride – our fine buildings now come tinged with a dusting of racial guilt. Meanwhile, victories in the class war seem thin on the ground. We are adrift.

What is striking about this evolving story of self, and I must point out that this is about the narrative, not the individual, what is most striking is that it does seem to cohere around a strong sense of grievance for slights endured – a mutual connection made through the collective swallowing of bitter pills made palatable by the odd-football win. Of course, many will simply feel this description does not fit and may take offence at any perceived slight on their scouse identity. But this project to manufacture a sense of separation is very real.

In my view, we are being sold a pup and it’s one that needs to take a trip back to the vet. While we gripe against lazy stereotypes in the media, we are, in truth, guilty of playing to them ourselves and too often take on these restrictive ideas as our own. Liverpool, and I say this with genuine love, is in danger of becoming an addict to its own class-A narrative.

Stuck in the past – where’s our sense of agency?

I’m conscious I need to explain how I think this works and why I believe it’s so dangerous to our health of mind and our future prospects. Let’s go back to that Liverpool Echo article and the popular argument. It has the benefit of simplicity. It goes like this… our sense of grievance, which is legitimately founded, is fuelling our independent, republican spirit, our demand for fairness and our rejection of Englishness, and this is entirely understandable and in some ways positive. It is up to the English and the English alone to make good or we’ll carry on our separate way. Should you be so minded you can buy the mug or the t-shirt and proudly proclaim your support for the Scouse Republic.

Now let me explain what I think is really happening. It ain’t pretty. Strap yourself in. I won’t be winning any prizes for popularity.

My argument is that our sense of grievance is fuelling not a positive assertion of independence but a downward spiral into insularity. The modern sense of political scouse identity that we are being encouraged to adopt, is a perversion of the positive and energetic forms that went before. It is forming primarily around negative assumptions – everyone hates us, we never get treated fairly, we have to fight for everything, and the outcomes that we want are largely beyond our control. There is a sense that the game is rigged against us, feeding a loss of faith in government authority both in Westminster but also increasingly at the local government level too. That’s one of the reasons why we’ve been seeing such low electoral turnouts. After all, if you view things that way, what is the point?

“Our sense of grievance is fuelling not a positive assertion of independence but a downward spiral into insularity. The modern sense of political scouse identity that we are being encouraged to adopt, is a perversion of the positive and energetic forms that went before.”

A primary feature of this outlook is pessimism and a loss of faith in the future. Our belief in our own agency to identify and solve the city’s problems and to conceive of big, ambitious solutions is becoming eroded over time. This is why today, in Liverpool of all places, we feel the pull of the past so strongly, expressed as it is in our stubborn defence of heritage (even when it makes no sense) or our determination to keep fighting old battles long after the social forces that made them have ceased to apply. Looking to the past is simply more reassuring because there is already a map to guide us and our obsession with the 1980s is at least in part, down to this nervousness about our future. It is also a politically convenient way of passing the buck.

As we struggle to find solutions to the problems we face and lose hope of better outcomes, our instinct as proud men and women of Liverpool is to throw our ire outwards, to say, ‘Sod you’ to the rest of England, which as the mooted source of our suffering is cast as the villain (the Scots, Welsh and Irish have our sympathies as they are also considered to be under ‘the yolk’). So then we double down on our own sense of uniqueness - we are hated because we are different - which is mostly a palatable rationalisation of our own sense of defeat. Of course, some people just go away, fire up their belly, and take charge of their lives, for example by setting up a business in places like the Baltic. Others just go away. Meanwhile, as a community, we re-commit to our grievances.

Unfortunately, despite the likelihood of a new government and a change in policy direction, there is little prospect of a shining knight riding over the hill to rescue us. We know this, don’t we? Our grievances serve no purpose in a battle we cannot win. All they do is fuel our sense of powerlessness. What we need to do as a city, as a people and as individuals is to reclaim our sense of power and agency and we can only do that by just doing it. Some, like Metro Mayor Steve Rotherham, will argue that this is why he is trying to gain more powers for the Combined Authority so that the region can exercise more control over decisions and that is right. But unless our leaders can find a way to turn their backs on the dominant pessimism of these times, they will dream only little dreams.

What ‘Scouse, not English’ and the backward-looking forever-focus on the 1980s offer us is a shrunken vision of our place in the world. A tiny Scouse Republic of Retreat - a new Pimlico. Sure, it doesn’t require a passport for entry and exit, but just like in that famous Ealing Comedy, it brings with it a wariness of the outside and a closing of doors at the exact time we need to be opening them. We should have no truck for this limited and carefully edited version of ourselves, this ‘Petty Scouser’ mentality. Instead, let’s stand tall, be open to the world and claim our confident place amongst it.

So, back to Thatcher and Toxteth

A little section here about our 1980s obsession and who stands to benefit. Let’s be clear. When in 2022 people re-raise folk devils from 40+ years ago as if they are still relevant, they are doing it for a reason. In Liverpool, it gives activists and elected representatives an alibi, allowing them to point the finger of blame outwards for the city’s sorrows, instead of looking within. It’s a way of avoiding scrutiny and of taking responsibility for inventing new stories and new sources of power and success. It’s time we all got wise to it. We deserve better.

Folk-Devil: In Liverpool, Margaret Thatcher was seen as a real-life Voldemort (Photo: Paul Marriott /Alamy)

More concerning though is what an over-zealous focus on the past communicates to the world outside and to the people we’d like to partner with. Forever talking about the 1980s pins us as irrelevant, backward-looking, and worst of all, passive in the face of the present. By using long-gone events to explain the outcomes of today, we risk turning ourselves into victims of history, still driven by events we cannot change. Time to let go.

What’s in a name?

At Liverpolitan, we’ve often been chided for adopting such a name. Why didn’t we use Liverpudlian? Nobody calls themselves a Liverpolitan. But exercising our agency means waving goodbye to insularity and engaging fully with the world around us. It is our signal that this country and in fact the whole planet is full of Liverpolitans making their way beyond the narrow confines of the city limits. What is remarkable about many of these people, is that though their lives have taken them elsewhere, they retain their passion for their ultimate home. They are a resource, they are legion and they are on our side. We should use them.

Last words to Joanne…

So what did the Mayor say that was so interesting? If we are being honest, it is the Left in the city that has been more prone to mining the past. You can argue it’s been an election-winning strategy, but that doesn’t mean it’s the right thing to do. So when the Labour Mayor of Liverpool tells us it’s time to face forward, I think we should listen. Here’s what she had to say.

“Every city has its challenges, and Liverpool is no different. But outdated scouse stereotypes and harking back to the 1980s does not define our city today. It is blatantly obvious that the city has undergone massive transformation and is continuously evolving. We have a dynamic culture and arts scene and major regeneration projects, whether it’s the growing health and life sciences sector, the film studios on Edge Lane, or Bramley Moore Dock. It is damaging when publications rely on the same old tired cliches and narratives about Liverpool, as it just perpetuates old myths that simply are not true. Liverpool is looking forward with optimism – maybe it’s time others do too.” Joanne Anderson, Mayor of Liverpool.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach

*Main picture by Alex McCarthy on Unsplash