Recent features

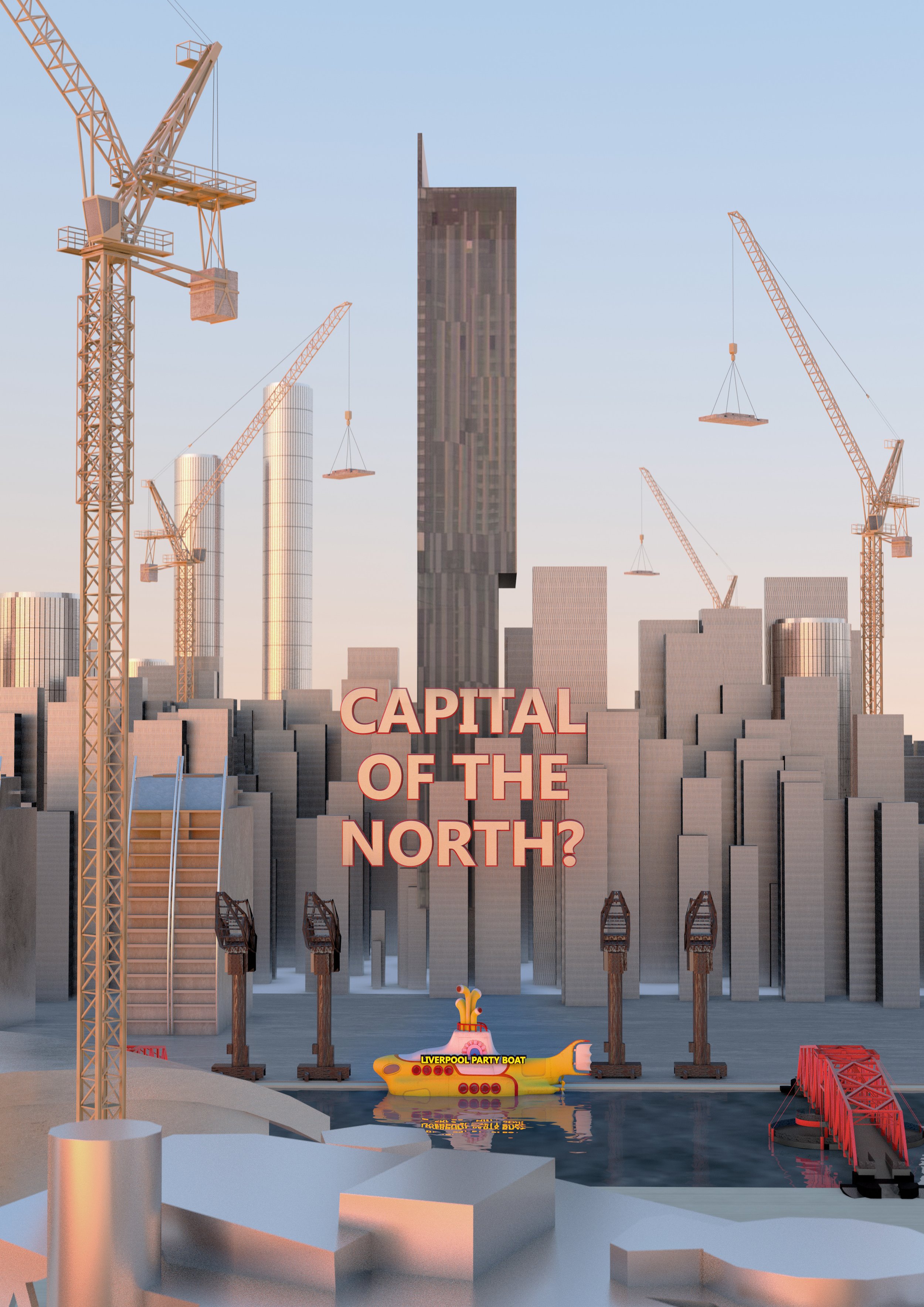

The Beatles: Inspiration or dead weight?

When does city pride in the Fab Four turn into a hindrance to future achievement? Jon Egan argues that the city of Liverpool is in danger of becoming a Beatles theme park, and its world conquering band a crutch to exorcise the painful intimations of our diminished relevance and prestige. In looking to the past, have we forgotten what made John, Paul, George and Ringo so special - their fearless embrace of the avant-garde, the contemporary and the new?

Jon Egan

There was something profoundly true and desperately sad in University of Liverpool lecturer, Dr David Jeffery's acerbic observation that "Liverpool is a Beatles' shrine with a city attached."

It is the dispiriting obverse to music journalist, Paul Morley's rhapsodic description of Liverpool as "a provincial city plus hinterland with associated metaphysical space as defined by dramatic moments in history, emotional occasions and general restlessness."

Jeffery's comments on Twitter appear to have been inspired or provoked by the recent announcement that Liverpool would be using a £2 million grant from Government to advance the business case for yet another "world-class" and "cutting-edge" Beatles' attraction on our hallowed waterfront. Presumably, it will be sandwiched somewhere between the Beatles statue and The Beatles Experience and conveniently close to The Museum of Liverpool and The British Music Experience with their not inconsiderable collections of Beatles artifacts and memorabilia. The exact nature of this new cultural icon remains a little unclear, however, amidst wildly differing descriptions offered by our City and Metro Mayors.

What is deeply depressing about this announcement is that it suggests that Liverpool is incapable of imagining any kind of cultural proposition that is not predicated on the seemingly inexhaustible allure of the four boys who shook the world.

There is of course a readily available and seemingly plausible justification for the never-ending Beatles' fetish, and that is the claim that they are the anchor for our hugely important tourism economy. Notwithstanding the implication that David Jeffery is right to suspect that the city is consciously morphing into a Fab Four theme park, I suspect that this is not exactly the whole truth. For Liverpool, The Beatles are a crutch, a cherished emblem of identity and importance used to exorcise painful intimations of diminished relevance and prestige.

In the novel, Immortality, Czech writer Milan Kundera tells the story of the man who fell over in the street, who on his way home stumbles on an uneven pavement, falls to the ground and arises dazed, grazed and dishevelled, but after a few moments composes himself, and gets on with his life. But unbeknown to the man, a world famous photographer happens to witness the scene and quickly snaps an image of the bewildered and bloodied pedestrian. He subsequently decides to make this picture the cover image for his new book and the poster for his international exhibition. For the man, a momentary misfortune freeze-framed, replicated and disseminated across the world, becomes the image that will forever define who he is.

The more we conflate the Beatles brand with the city's identity, the less space we have to imagine anything original, contemporary or remarkable.

In a sense, Liverpool is the City that fell over on the street, our external image is in significant part, defined by a succession of misfortunes, afflictions and tragedies that befell the city over two decades at the end of the last century. These events forged images, preconceptions and stereotypes that still blight us today and have never been successfully exorcised or replaced.

The Beatles hark back to a time before this blight, when Liverpool was in Alan Ginsberg's celebrated phrase, "the centre of consciousness of the human universe." They are, I believe, a therapeutic distraction from the task of making a different story or discovering a new identity.

Culturally, our Beatles fixation is unhealthy, debilitating and regressive. In fact, I fear we are reaching a point where The Beatles will become the single biggest impediment to any form of civic progression, or any serious project to make Liverpool important, interesting or relevant in today's world. If we are going to have a civic conversation about what kind of "world class" Beatles attraction should be erected at The Pier Head, my immediate impulse would be to recommend a mausoleum.

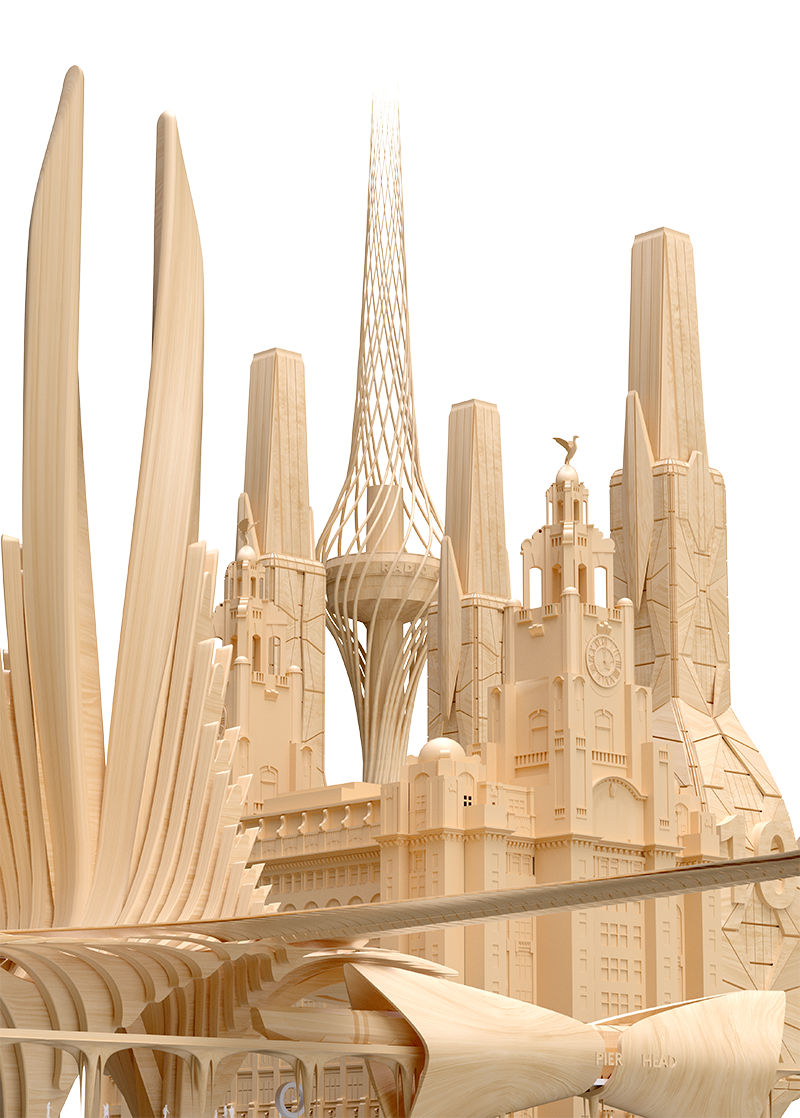

But perhaps a more imaginative and original idea was the one offered by the late Tony Wilson. That supreme Mancophile, Factory Records producer, Granada TV reporter and founder of the Hacienda nightclub was never held in particularly high regard in this city, especially following some tongue in cheek words of encouragement he gave to Club Brugge on the eve of their European Cup semi-final with Liverpool in 1977. Scousers may resemble elephants with respect to their prodigious powers of memory, but our skins can sometimes be just a tiny bit thinner. Tragically, Wilson's Mancunian persona and his tendency to lapse into casual profanity whilst presenting his project to civic decision-makers proved the undoing of his brilliant and visionary proposition for POP - the International Museum of Popular Culture. Pitched as the big idea for the European Capital of Culture, and the solution that would provide content for Will Alsop's audacious but otherwise functionless Fourth Grace, POP was a talisman for instant reinvention - a Beatles-inspired attraction without any reference to The Beatles. Alas it never happened.

Wilson had first dreamt of POP as an adornment for his own native city and a fitting celebration of its notable contribution to the history of modern popular music, but he soon realised that it was the right idea for the wrong place. He would often express irritation that when travelling in the US he would frequently have to explain where Manchester was by reference to its proximity to Liverpool - a place that people had actually heard of. And there was also the grudging recognition that at a time when Liverpool was "the centre of the human universe" globalising popular culture - Manchester could only offer us Freddy and The Dreamers. Even the outrageous charisma of Manchester United football god, George Best was derivative as he was often dubbed the 5th Beatle.

POP would not simply have been about popular music, it would encompass every facet of popular culture, every expression of contemporary creativity in film, TV, advertising, games, cars, sport, fashion, digital technology and consumer culture. And it was proposed for Liverpool because this was the place that spawned a phenomenon that reached the four corners of the Earth. It was a moment when the world discovered a common currency and a cultural vernacular intelligible to every ear.

POPs content would be dynamic and ever-changing, a continuous exposition of the new, curated by global creatives, designers and technologists. It would be Liverpool recovering its world city perspective and its capacity to invent and innovate - the pool of life, the birth canal for the extraordinary and the unprecedented. Its ingenious paradox was its implicit assertion that The Beatles did not make Liverpool, but Liverpool made The Beatles.

They monopolise our self-image occluding facets of identity and history now only half-glimpsed in the penumbra of a shadowy scouse dreamtime.

All of which is a million miles from Steve Rotheram's "world-class immersive experience" which he promises us will be more spectacular than a glass cabinet containing John Lennon's underpants. We can hardly wait.

If all we can possibly imagine are The Beatles etherealised into holograms - almost literally spectres from beyond the grave - then David Jeffery is right and Liverpool's once rich and cosmopolitan culture has collapsed into a black hole of redundant clichés. The more we inflate our Beatles offer and conflate their brand with the city's very identity, the less space we have in which to imagine anything original, contemporary or remarkable. Along with football (which at least tells new stories) they have come to monopolise both our external brand and our officially curated self-image, occluding facets of our identity and history that are now forgotten and suppressed, only half-glimpsed in the penumbra of a shadowy scouse dreamtime.

The Beatles have come not only to represent our brand, but have also helped to define our personality, attitude and accent - cheeky, chippy, sassy and defiant. As emblems of the 60s social revolution, they helped to forge and reify the idea of Liverpool as a working class city - or more accurately an exclusively working class city. As rock journalist Paul duNoyer, notes in his book, Wondrous Place, this is both a false and profoundly disabling imposition. Not only, as Tony Wilson asserted, are we the city that globalised popular culture, but we are a city that has contributed massively to every facet of culture, ideas and invention over the last 200 years.

The world's first enclosed dock and inter-city railway, together with the completion of the Transatlantic telegraph cable, are not only stunning achievements in technological innovation, but bolster the credible claim that globalisation began here.

The extent to which we have been willing to squander or disown the breadth of our cultural heritage was brought home to me in the febrile final stages of the European Capital of Culture bidding competition. Having commissioned pop artist, Sir Peter Blake to create a homage to his iconic Sgt Pepper album cover to remind the world, or at least the judging panel, of Liverpool's cultural and intellectual prowess, the task of deciding who exactly was worthy of inclusion was both fraught and enormously revealing. Apart from a few contemporary, and at the time highly topical creatives including the poet Paul Farley, artist Fiona Banner and film-maker Alex Cox, the principal criterion for inclusion appeared to be the directness or intimacy of connection to The Beatles. A lop-sided bias towards musicians, popular entertainers and Sixties icons meant no room for the likes of painters George Stubbs and Augustus John, poets Nathaniel Hawthorne and Wilfred Owen, novelist Nicholas Monsarrat, playwright, Peter Shaffer or even poet and novelist, Malcolm Lowry the author of the celebrated, Under the Volcano. Incredibly, until Bluecoat Artistic Director, Bryan Biggs' finally succeeded in persuading Wirral Council to erect a blue plaque on New Brighton's sea wall, there was virtually no public recognition that one of the 20th century's greatest and most influential novelists had any association with the Liverpool City Region.

Without questioning or diminishing the impact of the Mersey Sound poets (McGough, Henri and Patten) in the 1960s, their literary status is no way comparable to another unsung and forgotten cultural luminary with a significant Liverpool connection - C.P. Cavafy. Now acknowledged as one of the last century's most important and original poetic voices, Cavafy spent much of his childhood at addresses in Toxteth and Fairfield. Greek and gay, his poetry will forever be associated with the city of Alexandria where his family settled after leaving Liverpool. We do not know to what extent his formative years in the city helped nurture Cavafy's creative animus, but transience, up-rootedness and departure are woven into our narrative. Our sense of self and place in the world as Liverpolitans, owe as much to those who moved on, or merely passed through, as they do to those who stayed or settled here.

We are not, and never have been a monochrome canvass or a one trick city. Our culture is dense, deep and multifarious, formed by a hotchpotch of races, creeds and classes. For those tasked with defining a place and communicating its uniqueness to the world, there is always the temptation to reduce and simplify.

Brands, including place brands, are often conceived like Platonic forms - a distilled essence, fixed and immutable. But cities like Liverpool are neither simple nor static, and are thus frustratingly un-brandable. Described by Wilson as a place with "an innate preference for the abstract and the chaotic," our essence is pre-Socratic - unresolved, unpredictable and disconcerting. We know that port cities like Liverpool, Naples, Barcelona and Marseilles have historically been melting pots for ideas, influences and cultures - places where things never quite settled.

But their edginess is not merely a function of a perturbed diversity, it is also literal. It's connected to Marshall McLuhan's philosophical idea of right hemisphere sensitivity and the expanded perspective of what he terms acoustic space. Ports face outwards, they are perched on the precipice of a vast and formless abyss. It's an omnipresent reminder that there are no limits.

For Paul Morley, Liverpool’s character and identity - its ability to charm, entertain, inspire and infuriate - proceed from an inchoate restlessness and fidgety creativity. It's a place "where something happens, most of the time, leading to something else." But it seems like that creative energy and inventiveness have deserted us - or at least our leaders. What was once an animating pulse has been reduced to a piece of hollow rhetoric - a brand attribute.

It's sad that a UNESCO City of Music should have forsaken polyphony, and that we are continually stuck in a repetitive groove, narrowing our identity and stifling our capacity to be original (again). For this reason the very last thing Liverpool needs is yet another Beatles' attraction, even an immersive one.

So, OK, The Beatles were important, are important. They changed the world, but did they change Liverpool? We're still, I hope, the city capable of creating something else.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

Life after Joe: Ditching the Mayor won’t fix our broken democracy

There’s something nearly all of Liverpool’s political parties agree on - the need to abolish the office of directly elected city mayor. But are their positions based on principle, self-interest or just faulty logic? In 2022, the public should get to decide the question for itself in a referendum, but with such a one-sided campaign in prospect, there’s an acute danger that we’ll sleep walk into this vote without the chance of a properly informed debate.

Jon Egan

When nearly all of Liverpool’s political parties agree on something, you can bet it’s on an issue of mutual self-interest rather than in defence of any cherished principle.

As things stand, Liverpool’s voters will be invited, most likely in 2022, to decide whether to keep or dispense with the office of directly elected city mayor. It promises to be a rather one-sided campaign with the city’s three largest political groups (Labour, Liberal Democrats and Greens) all arguing for abolishing the post and returning to what they collectively describe as the “more accountable” Leader with Cabinet structure.

Even our recently elected incumbent, Mayor Joanne Anderson, is pledging to vote for the abolition of her own job, which begs the question, why she was so anxious to run for office in the first place? But of course, she was not alone. In the 2021 mayoral election, only two candidates - the Independent, Stephen Yip, and the Liberal Party's Steve Radford - were actually standing on a pro-mayor ticket. Indeed, following the unprecedented intervention by Labour's ruling National Executive to disqualify all three of the senior councillors on the original selection shortlist, both the Labour and Liberal Democrat council groups attempted to cancel the election by abolishing the role without recourse to a public referendum, until they were stopped in their tracks by polite reminders from their own legal officers that such a move would be unlawful.

There is an acute danger that we will sleep walk into this referendum without either a campaign or a properly informed debate. Voters will be asked to reflect on the need to learn lessons from euphemistically labelled "recent events" and fed the seemingly plausible line that one mayor is better than two. After all, why do we need a city mayor now that we have a metro mayor?

Of course, there is a shadow hanging over this whole discussion – one powerful argument for the case against elected mayors – which comes in the shape of the now under investigation and widely discredited former mayor, Joe Anderson. For some, he has become a walking metaphor and deal-sealing symbol of the dangers of too much power in the hands of one larger than life individual. But this is too important a decision for knee-jerk reactions. Our democracy demands that the subject be properly examined and debated. It’s too easy for us to be seduced by over-simplified and questionable arguments. We should think hard before dispensing with a model, that I would contend, has never been properly embraced or tried by our local politicians.

There is an acute danger that we will sleep walk into this referendum without either a campaign or a properly informed debate.

Before we head off to the ballot box (presuming we get the chance), there are some key questions we have to consider. Are mayors generally a good thing? Can they achieve results that old-style council leaders can't? Is there something specifically about Liverpool and the state of our local governance, our politics and our economic and social predicament that makes having a city mayor here particularly desirable or dangerous? And how are we to make sense of our experience of the mayoral model to date? Are the critics right that the concentration of power has been unhealthy or even corrupting?

But first… a little context. Let’s delve back into the city’s recent history to find out how we ended up in this mess. City mayors were an early prescription for what is now fashionably described as ‘levelling-up.’ The problem of a seriously unbalanced economy and underperforming urban centres was a matter of serious priority for the incoming New Labour government in 1997. The publication of Towards an Urban Renaissance - the report of Lord Rogers' Urban Task Force was a seminal moment in re-prioritising the importance of cities as vital engines for growth, innovation and national prosperity.

We’ve been here before - Liverpool’s democratic deficit

Harnessing that growth, it was implied, would require a new kind of energised civic governance similar in form and style to the dynamic leadership that had successfully regenerated European and North American cities such as Barcelona and Boston. In contrast, the fragmented committee structure of local government, then dominant in the UK, was seen as a recipe for old-school inefficiency and a failure of imagination. A new Local Government Bill (2000) set out the options to reset civic democracy. There was no coercion; just three choices: Leader and Cabinet (close enough to stay as you are), and two flavours of the big bang option for directly-elected City Mayors. Towns and cities were free to decide for themselves and unsurprisingly, councils overwhelmingly chose the least change option with only a handful willing to embrace the more radical mayoral restructure.

In Liverpool, however, the idea of a directly elected mayor aroused immediate interest, though admittedly not amongst our politicians. Instead, the city's three universities, its two largest media organisations (BBC Radio Merseyside and the Liverpool Echo) and a collection of faith leaders convened the ground-breaking Liverpool Democracy Commission in 1999. Under the chairmanship of Littlewood's supremo, James Ross, the independent commission brought together politicians, academics, and community and business leaders such as Lord David Alton, Professor of Urban Affairs, Michael Parkinson (now of the Heseltine Institute), radio presenter Roger Phillips, and Claire Dove, a key player in the local social enterprise movement. They took evidence from national and local experts and were shadowed by a Citizen's Jury to widen representation. In turn, the city council made a commitment to consider its recommendations and, if a mayoral model was advocated, to hold a public referendum.

From its inception it was clear that the commission was not simply evaluating the general merits of the available models, but was considering their applicability to Liverpool’s very particular local circumstances. Those circumstances included a wretched turnout of just 6.3% when a tired and divided Labour administration lost its majority in the crucial Melrose ward council by-election in 1997, the lowest ever poll in British electoral history. A Peer Review of the troubled council at the time by the Independent and Improvement Agency had painted a picture of lethargy, cronyism, an insular town hall culture, and wretchedly poor service delivery. Liverpool was acutely aware that its civic governance required a radical reboot.

Leaders run councils, Mayors run cities

The more general case for a directly elected mayor centred on its ability to reinvigorate local democracy, transferring the focus of civic leadership from the inner minutiae and manoeuvrings of the town hall to the wider city – its communities, businesses and institutions. As local government academic Professor Gerry Stoker put it when giving evidence to the Democracy Commission, “Leaders run councils, mayors govern cities.”

Stoker was by no means alone in advocating this radical change. Evidence from witnesses, community meetings, public surveys and the Citizen’s Jury converged on the same transformational proposition. Mayors could be convenors, able to galvanise civic energy by bringing multiple parties together in partnership. They would change the destiny of places in ways that our stilted and bureaucratic town halls could never hope to emulate.

Against this backdrop, the idea of giving every citizen the opportunity to vote for the city's leader seemed refreshingly progressive. It also offered a tantalising possibility - a radical break with party politics. Theoretically, the elected mayor system provides a level playing field for independent candidates. No longer would political parties with the networks and infrastructure required to support candidates in all of the city's wards be able to monopolise the system. Politics could be open, unpredictable and much more interesting and the talent pool from which to select a city leader was immediately expanded. Clever and experienced people from business and civil society would step forward to offer themselves for election.

But above all, it was the radical simplicity of the democratic contract that commended the mayoral model. No longer would local democracy be transacted behind closed doors, shrouded by arcane traditions and enacted through the inscrutable election-by-thirds voting system that somehow allowed political parties to lose elections but miraculously stay in power. With a directly-elected mayor, there would be visible leadership, clear and simple accountability and a transparent means of returning them or removing them from office.

By blaming the mayoral model for the shameful abuses and failures identified by Caller, our councillors are indulging in a transparently hollow attempt at self-exoneration.

It was for that reason that elected mayors were pitched as the antidote to voter disaffection, not just in Liverpool but across the whole country. Turnouts for local elections were in decline everywhere resulting in a widely acknowledged crisis of legitimacy.

Legitimate or not, one year before the Democracy Commission was founded, Liverpool’s voters had their say, overcoming their most ingrained cultural instincts to throw out what they knew was rotten. Liverpool's Labour administration was swept from power by an almost entirely unpredicted Liberal Democrat landslide.

So it would be a Liberal Democrat administration that would decide whether to adopt the mayoral model and respond to the unequivocal recommendation of The Democracy Commission. But they fluffed their lines, embracing instead the less radical option offered by the New Labour government – a Leader with Cabinet. Not for the first time, our political leaders knew best. Rather than allowing voters to choose their preferred model via the referendum they had promised, the council opted for the one that suited their own ends best.

Paradoxically, Liberal Democrat Council Leader, Mike Storey’s style and swagger were almost mayoral. He set up the UKs first Urban Regeneration Company (Liverpool Vision) and boldly calibrated a vision of the city as a European Capital of Culture. These were heady days, and many will now look back nostalgically on Storey’s early tenure as a time of almost limitless promise. So what went wrong?

Storey was instinctively attracted to the idea of city mayors and thought he could be one without having to navigate this dangerously Blairite and centralising heresy through his notoriously individualistic and anarchic Liberal Democrat Party. But Storey was constrained both by the instincts, prejudices and personal ambitions of his own political group, but perhaps more importantly, by the absence of an independent democratic mandate. His leadership rested on the confidence and acquiescence of his unruly Lib Dem caucus, but also on the compliance and co-operation of his highly ambitious Chief Executive, Sir David Henshaw - a challenging job at the best of times. From the outset, some had feared being left out in the cold by this high profile vote winner and knives were sharpened. Without a personal mandate from the public, it was difficult for Storey to face them down. The image of a beleaguered leader imprisoned and frustrated by an obstructive town hall bureaucracy was painfully and comically exposed in the infamous "Evil Cabal" blog. This was local government reduced to camp farce.

The fact is, Storey’s leadership and authority waned precisely because he was not a mayor. He lacked the clear constitutional and democratic authority to deliver on his mandate and to prevail over vested interests and personal agendas. At the end of the day, he was too much a part of a system that was still instinctively protective and self-serving.

Where power really lies

This may appear to be a subtle and rather academic distinction, but the source of a council leader's authority is always municipal rather than civic. The democratic process is indirect and opaque, and real power rests with councillors, not voters. It is councillors who choose the leader, and it is councillors who can topple them, even outside of the local election cycle. Ultimately, council leaders know who they are answerable to and are inclined to act accordingly.

Eventually Storey was forced to resign and after his nemesis, Henshaw, had departed, the Liberal Democrat regime lapsed into a familiar pattern of failure and chaos, mimicking its Labour predecessor. Before long it was being tagged as the country’s worst performing council, and was dumped out of office by an unlikely Labour revival. The compromise option of The Leader with Cabinet model had not ushered in the promised golden age of civic renewal, but only dismal continuity and an all too familiar story of town hall intrigue and ineptitude.

For the incoming Labour administration, the mayoral option was perceived as a threat, not an opportunity. Liam Fogarty’s Mayor for Liverpool campaign was gathering steam, and its petition heading towards the tipping point where a public referendum would have to be negotiated. For Fogarty, the slow implosion of the previous Liberal Democrat administration was evidence that the problems were systemic. He believed that only a new model which transferred more power to voters could fix Liverpool's dysfunctional municipal culture, and that the authority of leaders must rest on a direct personal mandate from the public.

Fearful that a referendum campaign would be a platform for a powerful independent, and in an act of supreme cynicism, Joe Anderson invoked a hitherto unsuspected provision of the Local Government Act to transform himself into an “unelected” elected mayor. It’s worth remembering that Labour’s adoption of the model was motivated solely by a neurotic phobia of a Phil Redmond (creator of popular TV soap-opera, Brookside) candidacy, rather than any intrinsic attraction to this radical new way of running a city. In truth, Liverpool Labour never believed in elected mayors and the shambles and shame of Anderson’s last days provided it with a perfect opportunity to dispatch the idea once and for all.

Boss politicians and the school of hard knocks

Anderson's sleight of hand once again deprived Liverpool voters of the opportunity of a referendum where the mayoral model could have been properly debated and explored. The fact that it was adopted without enthusiasm or any thorough consideration of its merits, is perhaps the explanation for what subsequently transpired. Anderson did not rule as a convening mayor - as envisaged by Stoker and advocated by the Democracy Commission - dispersing power, building coalitions, and using soft levers to nurture civic cohesion. He was an old-style Labour “City Boss” – in the style and tradition of Derek Hatton, Jack Braddock, Bill Sefton and a host of less memorable and notorious predecessors. Anderson’s approach was that of a fixer and deal-maker - a pugnacious “school of hard knocks” political operator who once threatened to punch a Tory Minister on the nose for claiming that austerity was over.

If Mike Storey was a council leader masquerading as a mayor, Joe Anderson was a mayor acting out the role of a traditional boss politician. What Storey lacked in terms of authority and mandate, Anderson lacked in terms of subtlety, collegiality and an overarching civic perspective.

During a mayoral hustings event in 2012 at the Neptune Theatre, an audience member posed the challenge, what is Liverpool for? A tricky question and one that demanded a perspective beyond the familiar horizons of the council budget and Tory assaults on its finances. Anderson seemed utterly dumbfounded. Only Liam Fogarty was able to grasp that existential questions like these cannot even be perceived, let alone resolved, from the myopic vantage point of a town hall bunker. Our politicians were simply incapable of rising to the challenge of a political role that required a radically different set of skills and a civic, rather than a municipal, mindset.

Which brings us to today. In effect, we have had a mayoral model, but we have never had a mayor in the way it was envisaged… as a radical antidote to a broken town hall culture.

It is the supreme irony that the case against elected mayors is now being framed on the record and reputation of Joe Anderson - the very embodiment of old-style Liverpool municipalism with its narrow and insular perspective. The argument that Anderson proves the perils of placing too much power in one person’s hands is a dangerous and misleading sleight of hand; a fallacy designed to obscure both historic truth and the complex considerations that should be informing this hugely important debate about how our city is governed.

The fallacy was set out quite pointedly in the 2021 Max Caller report, with its forensic exposure of Liverpool Council’s systemic municipal failure. In describing the governance structure of the city council, Caller observed:

“although the mayor is an authority’s principal public spokesperson and provides the overall political direction for a council, an elected mayor has no additional local authority powers over and above those found in the leader and cabinet model, or the committee system.”

Mayors are a dangerous idea. Independent candidate Stephen Yip threatened to end party political hegemony in Liverpool with only the meagrest resources. This is an eventuality that establishment politicians must join forces to thwart once and for all.

In effect, the "Leader with Cabinet" model now favoured by our local politicians, places exactly the same amount of power in precisely the same number of hands as the “discredited” mayoral model. In no way is it inherently more accountable or transparent. We are being sold a false prospectus, and one we know from our own recent history is no panacea. This is the classic ruse of the second-hand car salesman, and we need to look under the bonnet before it's too late.

By blaming the mayoral model for the shameful abuses and failures identified by Caller, our councillors are indulging in a transparently hollow attempt at self-exoneration. The “few rotten apples” alibi became the recurrent mantra to explain away the systemic dysfunctionalism exposed by the report. It was all down to the Mayor and a system that allowed a few powerful individuals to operate without adequate transparency or scrutiny. Or so the story goes. The solution is simple, get rid of the Mayor and all will be well.

But there was nothing extraordinary or atypical in Anderson's style, nor anything that was especially mayoral about the municipal culture or the way power was exercised. Caller's report is depressingly redolent of the Peer Review into the previous failed Labour administration and the chaotic end days of the subsequent Liberal Democrat council. This is simply what Liverpool local government looks like.

Multiple Mayors - other cities seem to manage it

We cannot make the mayoral system a scapegoat for a chronic and systemic failure of governance in our city. If, as its critics allege, mayors necessarily lead to an undesirable and dangerous concentration of power, then logically, wouldn’t we also need to seriously revisit our devolution deal and the post of Metro Mayor? Our politicians can’t have it both ways.

And neither should we be spooked by the “too many mayors confuse the voters” line. If it turns out that mayors are a good thing after all, then why should they be rationed? Mayors and Metro Mayors co-exist happily in London, Greater Manchester, South Yorkshire, the West of England, Tees Valley and North of Tyne. Cities in these areas including Bristol, Middlesbrough and Salford appear to be able to cope with the idea of different mayors exercising different powers over different geographic jurisdictions.

We shouldn't of course be surprised that our politicians are advocating for a return to the Leader with Cabinet system, when its most conspicuous difference to the “disgraced” mayoral model is that it would give them the exclusive power to decide who our City Leader should be. Rather than a direct popular mandate, Liverpool’s leader would be entirely beholden to councillors from within their own political group. Only in the looking-glass world of Liverpool politics can this be presented as more democratic and accountable. As the elected Mayor of Bristol, Marvin Rees recently argued in response to those advocating abolition of the post there. “It doesn't take much understanding of why the old system didn't work. Anonymous and unaccountable leadership, decisions made by faceless people in private rooms, and a total lack of leadership and action. The mayoral model makes the leader accountable - he/she is elected by the people of Bristol directly, not by 30 people in a room as in the old committee structure.”

If Liverpool votes to abolish its elected mayor and reverts to a system that has already proven unfit for purpose, we will weaken local democracy and diminish accountability.

But this is precisely the brave new system that we will be invited to endorse in next year's referendum and one that has already been tried and found wanting.

The lesson is that having an elected mayor is not a sufficient condition to deliver radical civic and political change, but it is a necessary one. The authority, legitimacy and wider perspective of the mayoral office is vitally important in making our municipal edifice work for the city rather than for itself.

Mayors are a good idea because they provide visible, directly accountable leadership. Their mandate enables them to speak up for their locality with authority and influence. We only need to look to London and Greater Manchester to see how mayors have been powerful and effective advocates for their cities and regions. But ultimately we need one who understands and actually believes in the role, which is why it is difficult to believe that Joanne Anderson's tenure is likely to fulfil the potential that the post could still offer to the people of Liverpool.

But as our councillors understand only too well, mayors are a dangerous idea. Independent candidate Stephen Yip threatened to end party political hegemony in Liverpool with only the meagrest resources and virtually no grassroots organisation. This is an eventuality that establishment politicians must join forces to thwart once and for all.

If Liverpool votes to abolish its elected mayor and reverts to a system that has already proven unfit for purpose, we will weaken local democracy and diminish accountability. And we’ll be doing it in the name of its opposite, bamboozled by the Humpty Dumpty logic of Liverpool politics where words mean whatever our politicians choose them to mean. We will also denying ourselves even the faintest possibility of breaking out from the cycle of dysfunctional party politics.

The elected mayoralty is the only chance we have to change the way our city is run. The tragedy is, we could lose this opportunity before ever having really given it a proper go. Someone needs to start a campaign, and soon.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

Liverpool Bombing: Calls to unite reveal what they really think of us

In the face of a terrorist attack, when much is supposition and information is still filtering in, it’s really important not to rush to judgement. Calm heads should, as in all situations, prevail. However, following the bomb blast from a home-made device in a taxi outside the Liverpool Women’s Hospital, it seems many are doing the complete opposite, crow-barring their agendas into a story that luckily didn’t appear to kill any innocents.

Paul Bryan

In the face of a terrorist attack, when much is supposition and information is still filtering in, it’s really important not to rush to judgement. Calm heads should, as in all situations, prevail.

However, following the bomb blast from a home-made device in a taxi outside the Liverpool Women’s Hospital, it seems many are doing the complete opposite, crow-barring their agendas into a story that luckily didn’t appear to kill any innocents.

One of the more curious examples could be found in Spiked Online in an article entitled ‘David Perry and the incredible heroism of ordinary people’. Speedily jumping onto claims that the taxi driver had quick-wittedly locked his passenger, Emad Al Swealmeen inside the car, after spotting suspicious activity, writer Tom Slater warmed to his task. “Time and again it is the public who are our last line of defence against this barbarism,” he concluded. And that may well be true, but the full facts are not yet clear in this case and Perry’s heroism is yet to be established conclusively. All that we do know at the time of writing, is that the video of the incident clearly shows that the explosion took place before the car had come to a stop. Why don’t we just wait and see and let the police piece it together?

The commentaries that swirl around these events reveal so much about the pre-occupations of those who would form the nation’s opinions. Liverpool’s Metro Mayor, Steve Rotheram was quick to set the tone, issuing a statement which said, “it would seem this was an attempt to sow discord and divisions within our communities. But our area is much stronger than that. We are known for our solidarity and resilience. Our diversity remains one of our greatest strengths. We will never let those who seek to divide us win.”

Merseyside Police Commissioner, Emily Spurrell, obviously had the same briefing sheet, ‘our region is known for its solidarity and resilience,’ she tweeted. Meanwhile, in the Liverpool Echo, Liverpool Mayor, Joanne Anderson was reported to have said, “For all of us who know that Liverpool is a tolerant and inclusive city – this will be hard to come to terms with. Over the next few days, as we learn more about what happened, we must all support each other and unite, as we always do, when times are tough."

Just in case anyone might point the finger, the Liverpool Region Mosque Network issued a statement too, appealing for “calm and vigilance”.

Take note of the consistent themes – tolerance, inclusivity, diversity, solidarity. They’ll be important.

But it was perhaps Liam Thorp of the Liverpool Echo who crystalised the thinking better than most. His article, ‘Terror won’t divide Liverpool, this city will be more united than ever’ drew praise from his own publishing team, with David Higgerson, Chief Audience Officer at Reach Plc using it to champion the newspaper as ‘a beacon of accurate, reliable information’. Some of their regular readers might beg to differ.

When you hear somebody say, ‘scousers do this, or scousers do that’ they’re really saying, ‘you must do this, you must do that.’

Liam was really on fire, sounding almost Churchillian. “It is in times of great adversity that the true colours of people and places shine through and it will come as no surprise to anyone who knows Liverpool well that the people of this city have stood up, united and pulled each other up again.”

Examples were given - an elderly man was provided with a wheelchair as he was evacuated from Rutland Avenue; over £60,000 and climbing has been raised on GoFundMe and Facebook for the driver – to pay for what exactly? They are aiming for £100,000 by the way. His wife Rachel described David’s condition as ‘extremely sore’. And of course, there was also this gem, “Or the brave bystanders who didn't think twice before running towards David as he fled that terrifying fireball - desperate to help him in any way they could.” I must have watched a different video. It all seemed a bit casual to me.

But Liam was only getting started, “Scousers look after each other - and when others try to jump on a crisis in this city to push their own divisive agenda, that will simply be rejected.”

It almost sounded like he was hinting at something else. I wonder what? But he had one final beat of the drum, “The Women's hospital represents the best of this diverse, inclusive, brave and brilliant city and each and every person here will have been horrified to see it targeted in this way.”

So there you go, just in case you are unsure. A bombing at a hospital, let alone a ‘women’s hospital’ is a bad thing. Are we all on the same page with that? Thanks Liam.

So what might we conclude from these very similar themed statements? Why do so many of the leading figures in the city feel the need to talk about diversity and inclusion and solidarity in the face of a terrorist attack? It’s not like that is the only option. You could just express your sympathy, appeal for calm and release the facts as they arise. Why go the extra mile?

What their spin on the Liverpool bombing reveals is their real concern. The more we hear the talk of scousers sticking together, of terror not dividing us, of our diversity being our strength, the more it reveals they don’t believe it. These sentiments hide a deep pessimism about their fellow citizens, about the unwashed and unruly. Why else would we need to hear their urgings for peace and a respect for difference? For some commentators, this desperate act of terrorism is the match in the hay bale. The trigger that they believe could ignite an orgy of violence. That civilisation is but skin-deep and we must be saved from our own worst instincts by their pious sermons. But history doesn’t support their view. Most people are decent. Most people strive to be fair. Most people do not resort to violence. When you hear somebody say, ‘scousers do this, or scousers do that’ they’re really saying, ‘you must do this, you must do that.’ We don’t need their advice to do the right thing. We’ve already figured it out for ourselves.

Truth is, leaders or those who want to be leaders like to look like leaders. And there’s nothing quite like a terrorist incident to summon up all that statesman or stateswoman-like pomposity. Don’t give them the chance. Turn off social media for the evening. Enjoy time with your family and friends. You won’t be missing anything important. Just blah, blah blah.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach.

Share this article

Vanished. The city that disappeared from the map

When I was a young child my parents bought me a truly wondrous gift ‐ an illuminated globe of the world. It was a magical object with the power to inspire and enrapture, but it also taught me two important, but hitherto unknown, facts about the world. The first was that my country, Britain, was very small. So small in fact that it was only possible to fit the names of two cities onto this tiny morsel of irradiated pinkness.

Jon Egan

When I was a young child my parents bought me a truly wondrous gift ‐ an illuminated globe of the world. It was a magical object with the power to inspire and enrapture, but it also taught me two important, but hitherto unknown, facts about the world.

The first was that my country, Britain, was very small. So small in fact that it was only possible to fit the names of two cities onto this tiny morsel of irradiated pinkness. The second lesson, that followed ineluctably from the first, was that my city clearly was important. As far as the world was concerned Britain could be adequately represented by only two places – London, its capital, and Liverpool, its global gateway. We were on the map, or at least we were then.

A few years ago, when passing through the John Lewis department store, I stopped to browse at a selection of highly impressive (but sadly not illuminated) globes. Britain remained within its familiar miniscule dimensions, but the cartographers had skilfully managed to inscribe on its terrain the names of not two, but five significant British cities – London, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and Glasgow. It merely confirmed what I had long suspected ‐ we were no longer important.

There is of course a serious point to this parable, and it is that we are not simply absent from physical maps, but also from the conceptual and metaphorical maps that shape policy and influence important decision‐making. Despite the incessant hype to the contrary, data from the Centre For Cities suggests we are making little progress in closing the performance gap with competing and emerging economic centres.

A well‐placed insider described Liverpool as “the city that has forgotten how to conjugate in the future tense.”

We have become peripheral ‐ largely outside the thought processes and priorities of political decision‐makers, investors, media commentators and influencers. Addressing and reversing this process – or putting Liverpool ‘back on the map’ ‐ has been, or certainly should have been, a guiding principle for our political and civic leaders over the last four decades. With a City Council mired in crisis and multiple criminal investigations, and the most recent State of The City Region (2015) report presenting a picture of chronic levels of ill‐health, worklessness and deprivation, it’s clear we still have a very long way to go.

For anyone wondering if the economic picture has improved since that last report was published, check out the tale of woe in the new Shaping Futures report, The Demographics and Educational Disadvantage in the Liverpool City Region (2021).

My own involvement with efforts to reposition and rehabilitate Liverpool’s external image has been deeply frustrating and depressingly circular. When in 2002 Liverpool was bidding to become European Capital of Culture, bid supremo, Bob Scott, suffered a heart attack in the closing stages of the process. City Council CEO, Sir David Henshaw took control of the bid, and invited myself as director of the agency that had devised the bid’s World in One City branding, and the Lib Dem’s political strategist, Bill le Breton, to review the campaign and communication messaging. This was an interesting and instructive exercise. Talking to people very close to the then Culture Minister, Tessa Jowell, and contacts equally close to the leading members of the judging panel, the feedback on Liverpool’s campaign pitch was not entirely encouraging. One of the most memorable comments from a very well‐placed insider described Liverpool as “the city that has forgotten how to conjugate in the future tense.” In a competitive process that was supposedly about regeneration and the role of culture in stimulating economic transformation, Liverpool had, until that point, focused almost entirely on showcasing its “great cultural heritage” and waxing nostalgically about its past glories as the Second City of Empire.

A radical rethink was needed, and fast if the city was to be ready in time for the judges’ second visit. We’d need a whole new bid narrative, rigorously disciplined messaging and a tightly scripted programme to change hearts and minds. The new story would be about the future ‐ a city applying its creative energies to embrace cutting‐edge culture, commerce and technology – and it worked. The only problem was that having won, we quickly abandoned the brave, new language and future‐focused vision. 2008 became, as Phil Redmond, Capital of Culture’s, last‐minute appointee as Creative Director, once testified, the proverbial “Big Scouse wedding” with Uncle Ringo on the karaoke.

Consigned to the second tier of UK cities, Liverpool had somehow become pigeon‐holed as economically and maybe even culturally irrelevant.

Fast forward to 2010 and the festival’s former marketing supremo, Kris Donaldson, arrives back in Liverpool to take up a new position as the city’s Destination Manager, only to discover that the promise of Capital of Culture as a platform to radically re‐position Liverpool had largely been squandered. Research commissioned by economic regeneration company, Liverpool Vision had suggested the city was perceived as quirky and entertaining, but news of its “regeneration miracle” was still a dimly perceived rumour amongst the nation’s influencers and decision‐makers. Without any significant expectation of success, I joined forces with journalist, political campaigner and former BBC Radio Merseyside broadcaster, Liam Fogarty and two local creatives (Jon Barraclough and Chris Blackhurst) to pitch for the city re‐branding brief that emerged from Kris’s sobering discovery. Our proposal was less of a pitch and more an indulgent exercise in provocation. Having initially been sifted out of the process by a dutiful underling at Liverpool Vision, Kris reinstated us onto the shortlist for interview. Our presentation began with a miscellany of quotes from ministerial speeches, broadsheet Op‐Eds and the authoritative musings of a polyglot of professional commentators. They were all opining on the need for economic re‐balancing and the incipient promise of that great new hope, the Northern Powerhouse. But amongst their mountain of words, one city was consistently and depressingly absent, and it was of course, Liverpool.

Permanently consigned to the second tier of UK cities, Liverpool had somehow become pigeon‐holed as economically and maybe even culturally irrelevant. The bold promise of 2008 had been replaced by fatalistic resignation, punctuated by occasional blasts of delusional bombast and mawkish nostalgia. As a result, Liverpool ceased to be discussed when the adults were in the room.

Winning the brief, with an ominous feeling of déjà vu and an almost Sisyphean sense of futility, we set out to equip the city once again with a future tense vocabulary and a story that would surprise and challenge the preconceptions of those we most needed to convince and convert. But like an aging soap star struggling with new scripts and plot lines, the city inevitably lapsed into its well‐worn phrases and crowd‐pleasing clichés. The It’s Liverpool campaign became less of a device to “package surprises” and orientate future ambition, but more an excuse to recycle familiar messages and tell the world what they already knew.

Fast forward another seven years to 2017 and I am sitting in the campaign HQ of the man bidding to become the first Liverpool City Region Mayor, the Labour MP for Walton, Steve Rotheram. We are discussing how to frame a transformational narrative for his soon to be launched election campaign. I find myself agreeing with him that devolution is the last chance saloon for a city (or City Region) being left behind by its competitors and too often ignored by those whose judgments and decisions shape its future. I think we may even have used the phrase “putting Liverpool back on the map” as shorthand for a project to reassert the city’s status as a Premier League player (forgive the clumsy football cliché) ensuring it once again became an integral component in the national economic narrative. I was increasingly hopeful that Steve’s refreshingly insightful analysis of the city’s deficiencies could be the prequal to a visionary devolution project. Four years on, and the consensus is that our Metro Mayor has yet to reset Liverpool’s trajectory or restore our status as an important economic or creative asset for the UK. If devolution was the last chance saloon, then the barman, with one eye on the clock, appears to be reaching ominously for the towels.

Four years on, and the consensus is that our Metro Mayor has yet to reset Liverpool’s trajectory or restore our status as an important economic or creative asset for the UK.

The initial stimulus for this article was the then imminent launch of Rotheram’s re‐election campaign in March 2020, before, of course, normality was put on hold by Covid and what we imagined were urgent political challenges dissolved into irrelevancy in the face of a global human tragedy. That earlier, never published version of this article, drafted in the format of an open letter to the Metro Mayor‐elect, was triggered by a series of events that acted as timely reminders of our reduced circumstances. Former Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne had used his resignation as Chair of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership to restate his vision of a rebalanced Britain where the “great cities of the north” (predictably we weren’t name‐checked) counterbalanced the wealth and prestige of London. But the tipping point for me, however, came on a day when Rotheram launched the latest phase of the Mersey Tidal Energy study, part of his big plan to recast the Liverpool City Region as an exemplar for sustainability and innovation. He might as well as not have bothered for all the attention it got. Instead, on that same day, a Simon Jenkins’ Guardian Op‐Ed calling for economic rebalancing, once again seemed to have been drafted with a map of Northern England where Liverpool was inexplicably absent. Twelve years after Capital of Culture and four years after devolution, the sad fact is that we are still not on the map.

The constructive, and at the time topical, section of the article was a positively motivated attempt to offer some suggestions for Rotheram’s critically important second term. Not that I thought I was especially qualified to provide such advice, but more to help stimulate a bigger, smarter and more diverse political conversation – in fact, the kind of energised democracy that devolution was designed to foster.

In a strange way Covid has given us more time, and an even more urgent imperative to take stock of where our City Region is heading. We need to be more radical, more imaginative and more willing to challenge the myths and shibboleths that have constrained thinking, blighted ambition and stunted potential.

So, in that spirit, here are five ideas about how we might help to remake and re‐position our city.

1. Appoint smart people – preferably from places more successful than Liverpool

Scouse exceptionalism and insularity are tragically compounded by a debilitating public sector culture. As the employer of last resort, our public institutions have evolved a defensive protectionist mindset that all too often fosters inertia and promotes mediocrity. I’m not necessarily advocating a Dominic Cummings‐style cull of staff and an invitation to assorted geeks, weirdos and misfits to replace them, but for devolution to make a difference it needs to be delivered by different people with higher levels of ambition, achievement and creativity. The kind of people capable of imagining possibilities beyond the recently launched hotchpotch of reheated pet projects and lame platitudes which masquerade as the city’s “transformational vision” for a post‐Covid future. What we need more than anything are people with a track record of delivery in a city or City Region that is palpably more successful than Liverpool. To extend the football analogy, we need a Klopp rather than a Hodgson; an Ancelotti or Benitez, not a Big Sam.

Rather than a being a dynamic galvanising body with a transformational agenda, our post‐devolution governance has somehow coalesced into an unhappy amalgam of Merseytravel and the Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) – a stifling bureaucracy with a highly developed aversion to any form of risk or innovation. For the next term to be successful, our Metro Mayor needs to transform the calibre, capacity and orientation of the Combined Authority. It remains to be seen whether the new Head of Paid Service can create a different dynamic and organisational culture or can inculcate the expansive perspective that has thus far been absent from our devolution project.

2. Have a story that makes sense, and then stick to it

Liverpool’s tragedy is that it is famous but no longer important. It means people already have an idea about who we are, what we’re good at and what we’re not so good at – like having an economy. The Combined Authority issued a brief to create a new City Region narrative, but the process seemed to be firmly in the hands of people who were too deeply immersed in the old dispensation, and too easily seduced by trite PR‐speak and marketing gobbledygook. So, here’s a radical suggestion – and one in the spirit of recommendation 1 – let’s appoint a world‐class creative with an international reputation to help us frame and articulate what this City Region is about. There are extraordinary flowerings of innovation and excellence here, but they currently look more like an advent calendar than a big picture. Rather than designing another procurement process and issuing yet another brief, why don’t we appoint somebody of the calibre of Bruce Mau, the Canadian branding and design genius? Let’s get a fresh set of eyes to re‐imagine the planet’s first “World City” and the place that globalised popular culture. Unless we can answer the existential question – what is Liverpool for? – we cannot hope to persuade people that we are still relevant today.

3. Get out there and spread the message

OK, I understand the electoral context and the reason why it was attractive for Steve Rotheram to launch the Tidal Energy study ‐ and a raft of more recent policy announcements ‐ in his own back yard, but guess what? No‐one east of Newton‐le‐Willows is taking any notice. The world is not watching or listening to Liverpool, so we need to get out there and tell them. That means doing the big announcements in London or wherever they’ll get noticed. It means having a Metro Mayor who is prepared and confident to do the awkward, challenging and high‐risk national media gigs. It means being willing to get on planes and fly to the four corners of the earth to spread the Liverpool (City Region) message. The great thing about not being weighed down with a plethora of statutory and service delivery responsibilities, is that a Metro Mayor can be our foreign minister, our ambassador – the kind of advocate and propagandist that this place has lacked and still so badly needs.

4. Find the causes and campaigns that make the story sticky and believable

As Boris Johnson so ruthlessly demonstrated in the Brexit and General Election campaigns, the world, the media ‐ and especially social media ‐ abhor complexity. Messages need to be sharp, self‐explanatory and sticky. They need to reveal and illuminate the bigger picture, and have the power to vanquish the myths, clichés and stereotypes that continue to blight perceptions of the City Region. We need to be able to definitively answer some key questions. What are the three most important ideas that can be the foundation of a new economic identity that gives our City Region a competitive edge and compelling new story? How do they connect? Who will they effect and why is it absolutely vital and non‐negotiable that we deliver on them? Whatever these ideas prove to be, underpinning them is a very simple ambition; to make Liverpool not just relevant, but also important – somewhere that is vital to the vision of a rebalanced, prosperous and successful UK.

5. Look for short cuts – if necessary, borrow someone else’s reputation and influence

It’s possibly the quickest win and the hardest pill to swallow, but we do have one big asset on our doorstep that could and should be mobilised to our advantage. George Osborne once observed that Manchester and Leeds city centres are closer to each other than the two ends of London’s Central tube line. Perhaps, from the distant vantage point of the Evening Standard editor’s office, he is unable to see the inconveniently positioned mountains or the fact that Liverpool and Manchester are even closer together! We even share two centuries of economic interdependence, and between us possess all of the attributes that sociologist, Saskia Sassen identifies as the defining characteristics of a global city. Abandoning football terrace rivalry to position Liverpool City Region closer to its burgeoning neighbour is both logical and necessary. An integrated transport authority, a shared policy unit and a merged LEP are all ways in which Liverpool City Region could begin to reposition itself within an expanded urban economy with the scale and asset base to counter‐balance London. Let’s not be constrained by redundant mindsets or arbitrary administrative boundaries. Liverpool – and Birkenhead – more than anywhere else can claim to have invented the template for modern civic governance in Britain, so why not pioneer new and liberating models designed to deliver the levelling‐up economic agenda, that will otherwise remain pious rhetoric?

Of course, these suggestions were offered in the confident expectation that the Metro Mayoral election was a mere procedural formality. Not even the implosion of Mayor Joe Anderson’s city mayoralty, the Caller Report and the national party investigation into Liverpool Labour were able to dent Rotheram’s majority. Labour’s almost Belarussian control of the City Region, and the fatalistic impotence of a fractured opposition, leaves us with a hollowed‐out politics where, notwithstanding the heroic efforts of Independent candidate Stephen Yip, the impetus for an inclusive civic discourse is blunted by establishment complacency and partisan insularity. A competitive electoral democracy, intelligent media scrutiny and strong independent civic voices (rather than meek subservience to the local state) are the prerequisites for energised politics and the possibility of a visionary civic project. So maybe the big question isn’t simply about what Steve Rotheram and Joanne Anderson need to do next, but how do we make space for genuinely transformational alternatives that might help Liverpool regain its former economic prestige and put us back on the map.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

“Better to break the law, than cause a war” - Arms Fair demonstrators in their own words

As political controversy erupts over October’s planned AOC Europe Electronic Warfare Convention, peace campaigners have hit the streets of Liverpool. As the Campaign Against The Arms Trade demonstrators marched from Princes Park to the city centre, Liverpolitan columnist, Paul Bryan, joined the throng, microphone in hand to hear what they had to say.

Paul Bryan

As political controversy erupts over October’s planned AOC Europe Electronic Warfare Convention, peace campaigners have hit the streets of Liverpool.

Determined to force the Council to cancel the event and prevent the ‘merchants of death’ from using the ACC Liverpool Exhibition Centre to sell their weapons and defence technologies, around 1000 demonstrators joined a rally on 11th September 2021 to pile on the pressure.

As the Campaign Against The Arms Trade demonstrators marched from Princes Park to the city centre, accompanied by Labour stalwarts Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell, Liverpolitan columnist Paul Bryan, joined the throng, microphone in hand to hear what they had to say.

Podcast

Broadcast, written and produced by Paul Bryan.

Photography by Daniel Watterson.

Music by GoodBMusic from Pixabay

All our podcasts can be enjoyed on Amazon Music and Spotify.

Share this article

WAH! What is it good for? Absolutely nothing

Are the Stop the Liverpool Arms Fair protests just another form of NIMBYism? Liverpolitan's Paul Bryan assesses whether ‘NOT IN MY LIVERPOOL’ is the real aspiration for many. Not in my backyard.

Paul Bryan

Are the Stop the Liverpool Arms Fair protests just a form of NIMBYISM?

If all it took to solve the world’s problems was a deep well of sincerity, then there can be no doubt that the latest demonstration in Liverpool against October’s planned AOC Europe 2021 Electronic Warfare Convention must be considered a stunning success.

Banners pleaded for ‘No more bloody wars’(is there any other kind?), ‘Nurses not Nukes’ (a reasonable-sounding request), and my personal favourite ‘Make scouse not war’. Although, it must be questioned whether vats of lamb stew, no matter how delicious, could form the basis of an effective defence strategy.

Of course, that sounds incredibly flippant and I don’t mean to be. There’s nothing wrong with wanting a better, kinder world. And anyone on the wrong end of a drone strike or a tyrannous regime could testify to the destructive power of modern armaments. That is, if they were still alive. But as I marched with and spoke to the demonstrators, I couldn’t help feeling a little confused. What is it exactly that they are asking for? That may seem like a stupid question. After all, the answer is found in the name of the campaign – Stop the Liverpool Arms Fair. And if I was in any more doubt the noisy protestor with the megaphone did her best to clear things up - the “What do we want? Stop the Arms Fair. When do we want it ? Now!” chant filled the air all day long. But to what end? If their pressure forced the ACC Liverpool Exhibition Centre to cancel the event, would one less piece of military hardware be sold in the world? Would the total weight of human misery be lightened in some way? If so, how?

Surely, the answer to those last questions would be “no” and “we’ve no idea”. Deep-down, I suspect the protestors know that too. To uncomfortably borrow an argument from the National Rifle Association for one moment, it’s people who kill people. The weapons are just the medium. And you can buy them in a lot of places. So if your actions won’t actually reduce violence in the places you protest to care about – Palestine, South Yemen, Syria – then what’s left? ‘NOT IN MY LIVERPOOL’ as one of the speakers shouted from the makeshift fire engine-come-stage, seemed to sum up the real limit of the aspirations for many. Not in my backyard.

The “What do we want? Stop the Arms Fair. When do we want it ? Now!” chant filled the air all day long. But to what end?

Which I suppose makes you wonder whether this is a futile cry in the Mersey wind – a posture to salve the conscience. Isn’t that the definition of virtue signalling?

In fairness, talking to people on the ground and listening to the speakers did reveal a whole poker hand of additional desires. Stopping arms sales to tyrannous regimes seemed to be a popular demand, while many (most) seemed to want to end all overseas arms sales full stop. I met a fair few who wanted to unilaterally dismantle the UKs armed forces and adopt a smile and hope strategy to international relations. Of course, given the profile of the crowd, plenty had their eyes on an even bigger prize. Nothing but the end of capitalism which they blame for all conflict, casually forgetting that the Romans and the Vikings were at it long before private enterprise became the de rigueur method of allocating society’s resources. I dare say the cave men were knocking each other on the head too.

My main sympathies are with those who argue for an end to foreign interventions. They hardly ever seem to make things better. Iraq, Syria, Libya and Afghanistan is quite the toll of failure. While the argument that it’s always about money and oil seem basic and vaguely ludicrous, surely the lesson from modern times is that you just can’t impose liberal values at the barrel of a gun in societies that don’t want them. More campaigning around that issue would, in my book at least, offer a far greater chance of easing the burden of war.

I met lots of wonderful people at the rally – union leaders, students, pensioners, a Sunday vicar, a veteran pilot of the Vietnam war, activists of different hues, and many more besides who had just come out for the day. But I didn’t for a minute think this was a typical cross-section of Liverpool society and I can honestly say, I have never met so many avowed pacificists in my life. Perhaps, this shouldn’t come as a total surprise. The Campaign Against The Arms Trade, which helped organise the event, has at least some of its origins in the Quaker movement – which has always taken the moral position that there is no justification for violence. Their’s is a utopian world where the lion lays down with the lamb. Where there is always room for talk. Where all it takes is an act of will to be better. “There is no place for war, only peace,” said an earnest Anya from Liverpool. And you can respect that view even if it feels counter to the sum weight of human history. She said there was no profit in war. Putting aside the obvious fact that there is, the forever outbreaks in conflict clearly show that someone benefits and it’s not always the obvious capitalist bogeymen.

While for many their pacifism seemed to be a point of idealistic principle, for others it was founded on personal experience, such as Anita from Wigan. I could really relate to her story. Her father served in the navy in WW2 and took part in the Battle of the Atlantic. He lost his youngest brother in the battle of Arnhem, while his two eldest brothers were captured and became Prisoners of War (P.O.W.) under the Japanese, which was generally not a pleasant experience. As a result, her father she said, “suffered from horrendous mental issues all his life and that is why I am anti-war.”

For Anita, being anti-war means laying down all of our nation’s weapons and refusing to fight. She wasn’t the only one who had this view. Far from it. Sadly, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. The answers to life’s questions are seldom as simple as taking a firm moral position, and laying yourself at the mercy of others can often have undesirable consequences. For every Gandhi espousing nonviolent protest, there are at least three murderous Pol Pots. Besides, in the 1980s, Labour’s flirtation with unilateral nuclear disarmament was electoral poison. Instinctively, most people are just comfortable with the idea that they need to be able to defend themselves. Barring the desperate, the zealots and those of pathological tendencies, nobody likes the idea of risking life and limb in bloody, brutal conflict. It really doesn’t have much to recommend it. But most of us know, that sometimes it’s inevitable. Sometimes you have to fight for what you believe in. Or be crushed. And I’d sooner go into a knife fight with a gun.

Labour’s flirtation with unilateral nuclear disarmament was electoral poison. Instinctively, most people are just comfortable with the idea that they need to be able to defend themselves.

While you could accuse the pacifists of naivety, they weren’t the only ones at the rally. In fact, they were almost certainly outweighed by the Left wing anti-war activists and their opposition to the arms fair appears to be far more tactical than moral, even if they wear all the accoutrements of offended outrage. In reality, they are seeking an altogether different type of utopia. The stars of the show included former Leader of the Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, Shadow Chancellor, John McDonnell, Labour MP Dan Carden, influential Liverpool Labour activist, Audrey White, and TV Actress, Maxine Peake. Unions such as the RMT were there too, and the Young Communist League and, of course, the Socialist Workers Party, who have more fronts than there are stars in the sky but whose banners are always recognisable by the use of that same give-away font. The list goes on – Black Lives Matter, CND, the Liverpool Friends of Palestine, and even a smattering of (although by no means all) local councillors. Liverpool Mayor, Joanne Anderson was notable by her absence.

Are these people pacifists? Well, some of them are certainly. The Left has a long tradition of being anti-war after all. But mostly they’re class warriors and their true beef is with the capitalist state. For them, the military is but an arm of the state and joining a campaign against an arms fair is an opportunity to turn the focus on imperialist warmongers, the profit motive and the racist ideologies that they believe underpin foreign adventurism. Hamstringing or completely eradicating the military and defence contractors is all part of the revolutionary playbook. It’s also a too-good-to-be-missed chance to prosecute their continuing and unhealthy obsession with Palestine. For them the campaign against the arms fair is but a proxy war, and that’s language they’d understand.

You can say what you want about Lenin, but at least he had some kind of plan. Granted it didn’t work out too well, but he did have the courage of his convictions. He was going to create a dictatorship of the proletariat, whatever it took. He didn’t hide his light under a bushel. But if Saturday was anything to go by, you can’t really say the same about the left wing demonstrators. Activist Audrey White may protest from the podium about the removing of the Labour Whip from the man who ‘still carries our (socialist) hopes and dreams’ (no I’m not talking about Keir Starmer), but the main focus of the rally was less about tackling the real causes of conflict and more about plugging into people’s innate sense of humanity. If Jeremy Corbyn was to be believed the weapons sold at the arms fair would be very targeted in the people they killed … “children in Gaza, children in Yemen, children in Somalia, children in Myannmar, children in so many places.” That really is some advanced technology. But is an exploitative pulling at heart strings any kind of argument?

Is this politics without the politics? Or is it lowest common denominator stuff, fetishizing on the weapons. Forget the context, feel the hurt.

One speaker, Haneen Awaad, 24 was introduced as a Palestinian Scouser – which feels like some kind of genetic super-breed of the oppressed

Corbyn was by no means the only one playing that game. One speaker, Haneen Awaad, 24 was introduced as a Palestinian Scouser – which feels like some kind of genetic super-breed of the oppressed. While describing herself as ‘born and bred in Liverpool’ she went on to say that all she’d ever known was ‘rockets, bombs, planes, tanks’. While the lives of Haneen’s grandparents have undoubtedly been touched by conflict (true of almost everyone of that generation in Europe) it seems unlikely that Haneen herself has had cause to fear military attacks in the streets of Anfield. Another speaker, Sarah Ashaika – a Syrian poet from Liverpool, who it was reported, has never been to Syria, regaled the audience with a poem that consisted of the names of dead Syrian children. Their involvement pointed to something hollow and performative about the rally in which people with no experience of the effects of weaponry gave testimony to the horrors of war.

Haneen excelled herself though. After telling the crowd how appalled she was at these ‘merchants of death’ visiting Liverpool, she then went on to evoke tropes about the Hillsborough disaster and the long-dead Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, to wrap up the (seemingly whole city’s) opposition to the arms fair as a typical scouse fight-back against injustice - which shows the way the region’s politicos continue to weave their own narrative of David and Goliath to forge a socially cohering, but ultimately toxic brand of localist exceptionalism. But more than that. Laying claim to Hillsborough to support your political campaign just felt ugly. But we shouldn’t be surprised – the idea that Liverpool is a continually oppressed city with a single socialist view of the world is the line we hear over and over again.