Recent features

Taylor Town Kitsch, Ersatz Culture and the Art of Forgetting

As Liverpool rolled out the red carpet for Taylor Swift, America's biggest pop star and her hordes of cowboy hat-clad 'Swifties' , the city's culture chiefs congratulated themselves on the global media coverage. 'This is who we are' seemed the message. But in this time of forgetting, John Egan wonders, is kitsch really who we are and what we want to be?

“If we don't know where we are, we don't know who we are,”

Jon Egan

It may seem perverse to even pose this question, especially as Liverpool was only recently judged by Which? as the UK's best large city for a short break by virtue of its “fantastic cultural scene”. But ask it I must. Despite once proudly wearing the title of European Capital of Culture of 2008, is Liverpool really a cultural city? To paraphrase the BBC's celebrated Brains Trust stalwart, C.M Joad, I suppose it all depends on what you mean by culture?

My worry is that Liverpool appears to be operating under an increasingly narrow and debilitating definition of culture, or at least, offering to the world a version of its cultural self that seems weirdly stunted, shallow and ultimately synthetic - something the American art critic and essayist, Clement Greenberg might have characterised as ‘kitsch’. Writing in 1939, Greenberg's essay 'The Avant-Garde and Kitsch' defined the latter as embracing popular commercial culture including Hollywood movies, pulp fiction and Tin Pan Alley music. He saw kitsch as a product of rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, which created a new market for “ersatz culture destined for those who, insensible to the values of genuine culture, are hungry nevertheless for the diversion that only culture of some sort can provide.” These mass-produced consumer artifacts, by definition formulaic and for-profit, had driven out "folk art" and authentic popular culture replacing it with what were essentially commodities.

One does not have to be a Marxist (Greenberg was) or a cultural snob (he was possibly one of those as well) to be slightly worried that Liverpool's cultural brand is beginning to lean too heavily in the direction of the kitsch and the hyper-commercial. It was a concern, first articulated in the run-up to Liverpool's hosting of Eurovision last year by the Daily Telegraph’s Chris Moss, “Liverpool has chosen Eurovision kitsch over protecting its history and heritage”, and explored further in my Liverpolitan article, “Liverpool's Imperfect Pitch”. A feeling that has only been exacerbated by the recent Taylor Town phenomenon.

For the somehow blissfully unaware, Taylor Town was a “fun-filled” council-funded initiative to transform the city of Liverpool into a Taylor Swift “playground” designed to offer a “proper scouse welcome” to the American pop star and her legion of fans before three sell-out shows at the Anfield stadium. This included commissioning eleven art installations each symbolising one of the artist’s 11 albums – everything from a moss-covered grand piano to a snake and skull-clad golden throne – all designed to be instantly instagrammable.

A golden throne inspired by Swift's 'Reputation' era forms part of Liverpool's Taylor Town trail conveniently located for lunch options. Image: Visit Liverpool.

Sure, Liverpool wasn't the only port of call on Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour to dress-up for the Swifties, but wasn't there something about the hype and hullabaloo that went beyond due recognition and celebration of a major musical event?

My queasiness about Liverpool's Taylor Town re-brand is more than mere snobbishness, or a patronising disdain for popular culture. Our willingness to conflate the city’s very identity with the persona of the American pop icon carries worrying echoes of Councillor Harry Doyle's “perfect fit” mantra between Liverpool and Eurovision. This is somehow more than just a smart bit of opportunistic marketing; it implies some deeper and integral affinity. Public pronouncements by Doyle and Claire McColgan, invoking the spirit of Eurovision, suggested Swift's visitation was seen as an epiphanic moment of self-realisation. In a spirit of almost quasi-mystical reverie, Clare McColgan explained; “the world can be a very dark place and in Liverpool, it’s light.”

If Taylor Swift has somehow become the embodiment of our cultural identity and ambition, what exactly have we become? The American cultural writer and scholar, Louis Menand observed, “in the 1950s the United States exported a mass market commercial product to Europe [rock n roll]. In the 1960s, it got back a hip and smart popular art form.” He is, of course referencing The Beatles and sadly it seems that we are once again being sold short on this cultural transaction.

“Liverpool's cultural brand is beginning to lean too heavily in the direction of the kitsch and the hyper-commercial.”

Despite Doyle's claim that her arrival “was very much in the spirit of the city's musical history”, Taylor Swift is not The Beatles. In the words of the Canadian feminist writer and blogger, Meghan Murphy she “will be forgotten in 20 years, which cannot be said for Janis Joplin, Carly Simon, Etta James, Leslie Gore, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Whitney Houston, Aretha Franklin, or Tina Turner... And none of those women made it on account of being beautiful or having a string of celebrity boyfriends. Certainly, they will not be remembered for their ability to command the hysterical attention of legions of young fans. They were just very good.”

Swift may be a global superstar, a role model and a performer with genuinely admirable philanthropic and compassionate sensibilities, but she is also according to Murphy, bland, manufactured and ephemeral - the literal embodiment of kitsch. Merely staging one of her concerts does not boost our cultural capital or say anything true or meaningful about who we are. For Harry Doyle, the sheer scale of global media coverage is its own justification. “So far, our city has been featured on just about every media outlet worldwide, including the Today Show in the US”, he excitedly claimed, as if a simple volumetric calculation was enough to establish cultural prestige.

Making “the city part of the show” to quote Claire McColgan, and building a civic and cultural brand by staging big events, was the thesis underpinning the city's post-Capital of Culture prospectus, The Liverpool Plan. Describing Liverpool itself as “The Great Stage” it prefigured a reality that those concerned about the condition and accessibility of our waterfront and parks are beginning to realise has troubling consequences. There may well be a perfectly credible argument for hosting large scale events and showcasing the city's architectural and heritage assets, but this is no substitute for what cities, once saw as their responsibility to promote and nurture culture in its widest sense.

So, do we need a different yardstick for what makes a cultural city? If Liverpool wasn't a cultural city, or had not been a cultural city, then I would in all probability not be here. When my father accepted a job in Liverpool it was intended as a stepping-stone to Dublin, the city where my parents had met and always aspired to settle down. It was the discovery that Liverpool possessed everything that Dublin promised, that persuaded them to put down roots in a place that satisfied all their cultural appetites. This was a time when both UK and international opera and ballet companies regularly visited our city, when cutting-edge theatrical productions had their pre-West End runs in the city's array of thriving theatres. It was also the time when Sam Wanamaker was transforming the late lamented New Shakespeare Theatre into what The Guardian described as “one of the first multi-strand art centres in Europe” - a venue that was open 12 hours a day, staged contemporary theatre as well as films, lectures, jazz concerts and art exhibitions and put on “free shows for workers every Wednesday afternoon.”

“Taylor Swift may be a global superstar with admirable philanthropic sensibilities, but she is also bland, manufactured and ephemeral - the literal embodiment of kitsch.”

Moss-covered piano inspired by Swift's 'Folklore' era, one of eleven exhibits that made up the Liverpool Taylor Town trail. Image: Visit Liverpool

From the 19th century onwards, culture was embedded in Liverpool's civic project, the city’s self-image being proudly cosmopolitan rather than prosaically provincial. “High Art” might not be the exclusive criterion for what constitutes a cultural city, but it was, for a time at least, integral to Liverpool’s claim to that status. Now it would appear that culture has no intrinsic value other than as a means to an end. Taylor Town was, in Doyle's words, “much needed PR the city needs to attract investment and visitors.”

The irony is that a positioning or investment strategy focused on big events and blitz publicity is quite probably a less effective strategy than one focused on stimulating cultural quality and diversity of offer. Events may deliver a short-term boost to the tourism and hospitality sector, but smart cities understand that the depth, quality and originality of their cultural offer is what draws investment and attracts and retains people. Once again, it might be instructive to look to our regional neighbour, Manchester for inspiration. The Manchester International Festival (MIF) not only reveals a city that, unlike the organisers of LIMF (Liverpool International Music Festival), understands the meaning of the word "international," but is also a masterclass in intelligent place marketing. MIFs inspired, left-field commissions and collaborations are deftly configured to spell out one simple message - “Hey, we're just like London.” In other words, we're the sort of city that's ready-made for banished BBC executives, relocating corporates, boho entrepreneurs or the English National Opera (ENO). Manchester benchmarks its cultural strategy against cities like Barcelona and Montreal, disruptor second cities harbouring global ambitions.

There was a sad inevitability about the ENO relocation to Manchester after Liverpool had failed to make it beyond the shortlist. Liverpool's city leaders offered a flimsy defence of their laissez-faire approach to pitching - that this was a process-driven exercise where lobbying and advocacy were superfluous and potentially counterproductive. Yet as a well-placed Manchester source explained, “Yes, it was process-driven, but the timing worked for us, coming [so soon] after the Chanel Show which secured exactly the right kind of media coverage.” (Note - quality not quantity) “But the key was the availability of a versatile and conveniently available performance venue designed by Rem Koolhaas, that didn't really have a defined function or use-strategy.” The commissioning of The Factory / Aviva Studios was an audacious exercise in the ‘build it and they will come’ approach to urban regeneration, and proof that Manchester, like the Biblical wise virgins, is a city always primed with a trimmed wick and plentiful supply of oil.

Probably, a more significant consideration was the perception that Manchester had an audience for opera whilst Liverpool possibly did not. One of the most depressing episodes in my professional life came during a discussion with Liverpool's big cultural players whilst working on ResPublica's HS2 for Liverpool advocacy project. A prominent, though now departed, head of a prestigious cultural institution, lamented that they would love to deliver a more ambitious programme (as they had in 2008) if only they could “attract an audience from Manchester.” Yet as the success of Ralph Fiennes' Macbeth production at the Depot venue proved last year, this comment is as ill-informed as it is profoundly dispiriting.

“From the two fake Caverns and tat memorabilia of Matthew Street to the anodyne mediocrity of “The Beatles Story”, we are now celebrating what was once subversive popular art in the guise of the mass-produced ersatz culture to which it was once the antidote.”

The Beatles Story: A fake grave cast in authentic-looking granite to a fictitious character Paul McCartney claims he ‘made up’. Could this be any more ersatz or is it just ‘meta’?

Photo: Paul Bryan

For all its sophistication and legacy of transformed cultural assets, there is still a whiff of utilitarianism about Manchester's approach, and a view of culture as primarily an instrument of economic regeneration. Hence an emerging new strategy with a greater emphasis on what they term “cultural democracy” with a more equal and diverse distribution of cultural resources and opportunities.

Notwithstanding the undoubted quality of our visual arts assets and collections, Liverpool's performing arts offer is now sadly diminished and, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra excepted, is hardly commensurate with what you’d expect of an aspiring cultural city. If Liverpool is to entertain genuine claims to that title, then maybe we need another definition that isn't founded merely on physical assets or an eye-catching events programme?

For American essayist and poet, Wendell Berry “culture is what happens, when the same people, live in the same place for a long time.” For Berry “same people” doesn't entail ethnic homogeneity. His own Appalachian culture is a heady brew of English, Scots Irish, Cherokee and African influences that even a fledgling Taylor Swift, once wanted to get a piece of. His definition is closer to what Clement Greenberg saw as the antidote to kitsch - “folk art”. This is culture with roots, with an organic and intimate connection to place, with a character, accent and disposition that are distinctive and inimitable. By this yardstick, cultural cities are not just places that stage culture or boast a wealth of cultural assets, they also cultivate and disseminate it. It is in this sense that Liverpool can perhaps advance its most convincing claim to be a cultural city.

Liverpool's culture is as much an ambience and attitude as it is an archive of expressions and artefacts. It emerges in creative convulsions that emanate from a deep geology, a substratum of shared stories and memories. In the 1960s, it was Merseybeat, the poetry of McGough, Patten and Henri, the forgotten genius of sculptor, Arthur Dooley, and the phantasmagorical humour of Ken Dodd. (Are the jam butty mines of Knotty Ash just charming whimsy or, like Williamson's Tunnels, secret portals into the arcane depths of Liverpool's collective unconscious?). The early noughties, as the city began to dream of becoming a European Capital of Culture, happily coincided with another creative spasm, as Fiona Banner was shortlisted for the Turner Prize, Paul Farley won the Whitbread Poetry Prize, Delta Sonic Records were trailblazing Liverpool's third musical wave, and Alex Cox was back in town collaborating with Frank Cottrell Boyce on their, as yet unrecognised masterpiece, Revenger's Tragedy.

“Memory is the alchemy that transmutes the base metal of the everyday into the life-enhancing elixir of an authentic culture. But we live in a time of forgetting, of uprootedness, fracture and disinheritance, and even a city famed, and often derided, for its obsessive nostalgia, is not immune from this pervasive fixation with the immediate, the superficial and the kitsch.”

It's not just the social realist triumvirate of Bleasdale, Russell and McGovern whose writings are moored in the anchorage of their home port city. For novelists like Beryl Bainbridge, Nicholas Monsarrat and Malcolm Lowry, Liverpool looms and lurks in the shadows of their fiction even as a point of departure or an unspoken absence. For two contemporary Liverpool writers, the city is an object of almost erotic communion. Musician Paul Simpson's gorgeously poetic memoir, Revolutionary Spirit, and Jeff Young's Ghost Town are immersions in secret treasuries of memory and miracle. Young is Liverpool's cartographer of the marvellous, tour guide to our fevered Dreamtime for whom Liverpool “is the haunted place of remembering.”

Memory is the alchemy that binds past and present, that invisibly entwines the living with the dead. It's what transmutes the base metal of the everyday into the life-enhancing elixir of an authentic culture. But we live in a time of forgetting, of uprootedness, fracture and disinheritance, and even a city famed, and often derided, for its obsessive nostalgia, is not immune from this pervasive fixation with the immediate, the superficial and the kitsch. In a blisteringly brilliant essay in The Post, Laurence Thompson poses the question, why is Liverpool unwilling or unable to recognise the creative achievement of filmmaker and “great visual poet of remembrance,” Terence Davies, and his seminal trilogy Distant Voices, Still Lives?

“That such an impressive work of art came both from and was about Liverpool seems worthy of commemoration. Yet it’s impossible to imagine the Royal Court commissioning a major contemporary playwright to adapt a stage revival of Distant Voices, Still Lives... I’m not advocating Davies’s memory falling into the hands of the usual custodians of Liverpool’s heritage. What’s the point in putting up a blue plaque commemorating the original Eric’s when the current Eric’s is so unbelievably shite? But the choice between amnesia and kitsch must be a false dichotomy.”

The French seem more inclined to remember the seminal films of Terence Davies, than Liverpool, the city of his own birth. A retrospective held at the Paris Pompidou Centre in March 2024.

Alas, it seems we are increasingly opting for kitsch, not just in terms of our desire to bask in the reflected aura of Eurovision and Taylor Swift, but also in how we package and commodify our own cultural legacy. From the two fake Caverns and tat memorabilia of Matthew Street to the anodyne mediocrity of “The Beatles Story”, we are now celebrating what was once subversive popular art in the guise of the mass-produced ersatz culture to which it was once the antidote. Kitsch's suffocating omnipresence is a soporific that dulls memory and transports us into its own featureless geography. “If we don't know where we are, we don't know who we are,” explains Wendell Berry. For Berry, culture, identity and place are a sacred trinity without which human society withers and sinks into the shallow abyss that G.K. Chesterton termed the “flat wilderness of standardisation.” A time of forgetting is also a time of false belonging. Polarised politics, bitter culture wars and horrifying street violence are in different ways a thrashing around in search of connections to something enduring and meaningful in the bewildering Babel of post-modernity.

Consigning an artist of Terence Davies' stature to the margins of oblivion is sinful enough, but it is emblematic of a deeper estrangement and disconnection. A city that squanders its World Heritage Status, that's indifferent to its own cultural history and cheerfully embraces an architectural aesthetic of shabby and soulless mediocrity, is forsaking its very identity. In the spirit of Louis Aragon's Le Paysan de Paris, Jeff Young chronicles Liverpool’s neglectful disregard for the overlooked, the curious and the idiosyncratic, for the magnetically charged spaces and landmarks, like the sadly demolished Futurist cinema, that are the coordinates of our collective remembering. Ghost Town is an odyssey in search of a submerged city, drowning under the dead weight of the bland and the banal.

“The magic is leaching from the city, the shadows and alleyways are emptying, and so we walk through wastelands where the magic used to be, we gather autumn leaves from gutters and dirt from the rubble of demolished sacred places.”

Identity and culture are rooted in the original, the distinctive and the unwonted, in things that should be reverenced, not wilfully expended.

At the conclusion of his Gerard Manley Hopkins Lecture at Hope University earlier this year, I asked Jeff, how do we breach the chasm that seems to separate those who love the city, from those who govern it? There isn't a simple answer, but it must surely involve some thoughtful consideration of what it means to be a cultural city. Culture in its authentic form, is salvific. Being connected to a place, its story and to each other is to fulfil one of our most basic human yearnings.

For now, at least, the circus has left town. Eurovision and Taylor Swift have moved on to the next “destination.” But if we want to get in touch with our culture, we need to see through the eyes of poets and artists like Jeff Young and Terence Davies, to look beyond the empty stage for something part-buried and only half remembered - the immeasurable richness of a cultural city.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Main Image: Paul Bryan

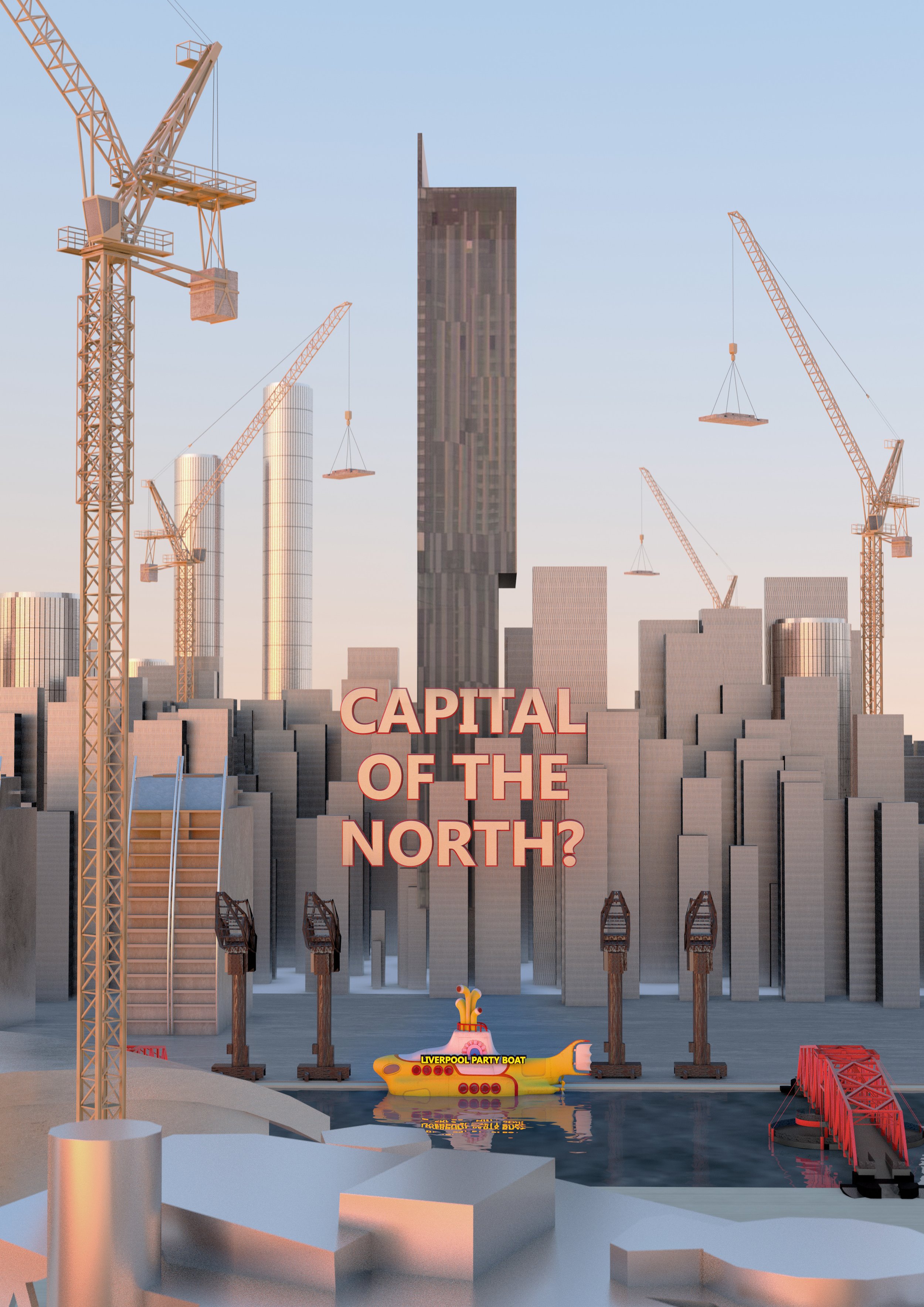

The Scourge of Northwesternism

In England’s Northwest, one city blooms while another withers on the vine. Manchester is reaching for the skies while Liverpool stares at its navel. A cancerous rot is eating away at my city’s self-esteem. It deserves a name. I call it Northwesternism.

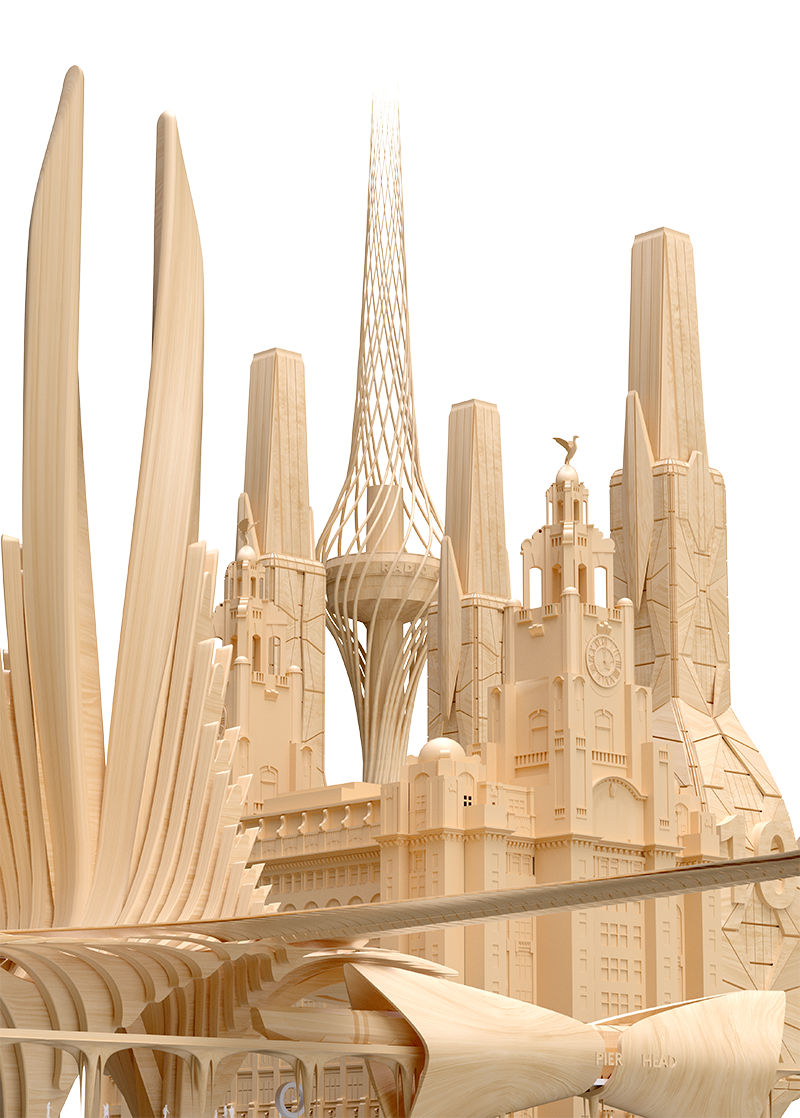

Michael McDonough and Paul Bryan

Does anyone else notice that simmering sense of defeatism running through pretty much everything Liverpool does today? Whether it’s politics, culture or architecture there seems to be a crushing sense of meekness dragging down or at the very least blowing off course the city’s regeneration. You don’t have to look too far to find the evidence, from Liverpool’s proposed new stumpy, tall buildings policy, to the attempts to rejuvenate the high street with low-class tat like bingo and go-karts. Even our waterfront indoor arena was built patently too small to compete for the best music acts. We seem to have gotten good at hiding ourselves under a rock.

I noticed this sense of defeatism running through what was otherwise a riveting read by Jon Egan in his recent Liverpolitan article, ‘It’s Time to Get Interesting’. Examining Liverpool’s fallen place in the world, he searched for a solution and built it on the stoniest ground. Believing that “Liverpool’s claims to regional dominance is a boat that has long since sailed”, he called it an “unavoidable truth” that Manchester is now established as the region’s capital. Then from that premise he pitched an idea - unable to escape our fate as the North West’s second fiddle, we should lower our goals and find a workaround based on our outsider status and our sense of difference. He suggested we do this, by making ourselves ‘interesting’, something that comes naturally to us because it’s kind of in our social DNA. Austin, Texas was held up as a possible model to follow, a city which carves out its place in the world under the banner, ‘Keep Austin Weird’.

Now, I know that Jon doesn’t intend to cast Liverpool as a dancing monkey at a freak show, and you could argue that the economic data points to the truth of our cities relative position, but I don’t really see this strategy solving the myriad economic and social problems that Liverpool faces. It doesn’t sound all that far removed from the innovation strategies that have largely failed to deliver innovation. But my biggest problem with it is that it’s premised on pessimism. For me the race to become interesting or to live into our sense of cultural difference is just a way of rationalising our lowered position.

For me this all smacks of a cancerous rot eating away at Liverpool’s self-esteem. A long gestating idea that Liverpool cannot and will not ever again be more than an offshoot of the aspirations of another relatively small, regional UK city. Who the hell wants that? It’s a view that forces us to lower our horizons and settle for less and it has only one direction of travel - from city to village in countless, tiny steps.

I’m sad to say I increasingly see evidence of this sense of cultural pessimism all around me. They say, make no small plans, but we’re becoming experts at it, and you’ll find a whole breed of shamanistic professionals, activists or NIMBYs throwing shade on the very idea of planning big, going tall, and growing our economy. Sometimes they even reject the very concept of competing. This low growth rationalisation of defeat is usually wrapped in warm fuzzy words like sustainability or human-centred development, while a more optimistic view is seen as foolishly utopian or an apologetic for predatory capitalism. Yet just a few miles down the road things look quite different. And for those who want more, it’s often easier to just pack their bags and relocate.

Too much of our professional class appears to have succumbed to the Liverpool-killing long game of ‘regionalism’ - the modern face of managed decline. You can hear it in the language, and see it in the initiatives. It’s almost as if a subconscious decision-making 'culture' has pushed Liverpool to the periphery. Seeing yourself as secondary or even tertiary is now so ingrained that Liverpool no longer feels it can compete with what is merely another UK provincial city. So instead we see attempts to 'partner', 'work with’ and ‘align with’ Manchester-based institutions, which feels more and more like surrender rather than balanced cooperation.

Of course, ego won’t let us admit this and any self-respecting scouser will bristle at the very idea of Manchester as the regional capital; dark insecurities soothed by talk of world-class this and world-class that. Perhaps if we host Eurovision we’ll feel relevant again? But it doesn’t mean this humbling process isn’t happening or hasn’t already happened right under our noses. It’s all part of the perpetual grind of what I call ‘Northwesternism’. It’s part policy and part psychology – the forces of economic agglomeration, and political influence colliding with the endless boosterism of a perpetually on the front-foot city, culturally pump-primed by a media only too willing to play along. Drip, drip, drip bleed the jobs and opportunities; young lives transfused away. On the Liverpool side, we put the blinkers on, our taxi drivers famed for telling all and sundry ‘things are getting better’. Do they still say that? Over time, our inferiority complex becomes so ingrained that when the subject of the problematic Liverpool-Manchester relationship is brought up it’s laughed at or sneered at, dismissed as some kind of conspiracy theory. But then you just have to look at our graduate retention numbers. Deep down we just know.

“The idea that our two cities, separated by a mere 32.9 miles are not in competition with each other is a supreme act of gaslighting.”

Anthony Murphy of the University of Liverpool Management School recently posted on Twitter that “Smart young people from the city see it that way - flocking there for decent, well-paid jobs”. He wasn’t talking about Liverpool. Sometimes, being the capital is a state of mind. They have it, we don’t and they have the jobs too.

Our subconscious defeatism makes us smaller, lesser and this shows across so many sectors. We've almost got Stockholm Syndrome. I believe that Liverpool's malaise and rudderless direction have been a wonderful gift to Manchester's leaders creating a workforce that only ever travels east in the morning.

‘Northwesternism’, the passive acceptance that Manchester is the region’s dominant Silverback, is for me Liverpool’s greatest challenge in re-asserting itself as a major city. Our leaders should go into every regional partnership meeting with their eyes open, asking themselves ‘what’s in it for us?’ In Jon Egan’s article, he discussed how ‘Manchester is definitively and inexorably set on its own northern trajectory’. That being the case, why on earth does our Metro Mayor Steve Rotherham continue to insist on working so closely with Manchester’s Mayor, Andy Burnham? They have their own trajectory and set of goals, and they are not the same as ours. Increasingly, it feels to me as though Andy Burnham is entertaining one of the Greater Manchester boroughs – once Liverpool, now Manchester-on-Sea.

Do a little research and you’ll discover Mr Rotheram more often than not is stood behind Andy Burnham in public images and media features. Burnham is always positioned at the centre. There are no calls for Rotherham to be christened the ‘King of the North’; no bets placed on Steve Rotherham to be a future Prime Minister, and certainly no column in the London Evening Standard. You could ask why any of this matters, but in an era of image and soft power projection, Liverpool is suspiciously absent from the national conversation, a recommended city break in the Telegraph, but fringe where it counts.

Until Liverpool rejects ‘Northwesternism’ and the slow but steady spread of Manchester’s well-oiled and expanding ‘psychogeography’, then Liverpool cannot confidently look outward to the rest of the world as it will be forever undermined on its own doorstep.

I think we have to wake up and fast. And now Levelling Up Secretary, Greg Clarke, has just invited Sir Howard Bernstein, Manchester City Council’s former Chief Executive to help draw up a vision for our city’s future, something our own council has singularly failed to do themselves. He’ll be joined by Judith Blake, former Leader of Leeds Council, Steve Rotheram and an as yet unnamed person from the business sector. Excellent administrators though they are, I can’t help wondering if Howard and Judith will have Liverpool’s best interests at heart. Maybe they will. We can hope for the best. Would Bernstein propose anything that might weaken Manchester’s grip given he spent his whole career building their success? Would he want to champion our promising games industry or eye it as yet another prospect to wine and dine? Would Judith support a significant expansion of our legal sector given Leed’s strengths in that area? At the very least, we need to stay awake to our own interests at all times and turn a deaf ear to those who say competing is for chumps – that Liverpool can exist in its own utopian bubble where the lion lays down with the lamb.

“This low growth rationalisation of defeat is usually wrapped in warm fuzzy words like sustainability or human-centred development, while a more optimistic view is seen as foolishly utopian or an apologetic for predatory capitalism.”

MANCHESTER nakedly pursues its own interests. There’s nothing wrong with that – I’m not passing moral judgement but the idea that our two cities, separated by a mere 32.9 miles are not in competition with each other is a supreme act of gaslighting. The fact that so many members of Liverpool’s political and business communities have fallen for it, like hostages besotted with their kidnappers, is evidence of either a stunning lack of self-awareness or a cynical judgement on moving as the wind blows, taking advantage of a new reality while tucking the loser in bed and whispering in their ear that everything will be alright.

The decision in 1997 to approve Manchester Airport’s second runway over expansion at Liverpool was not in our interests. It was in theirs. The building of Media City in 2007 with its gravitational pull on all TV production led to the closing of our own Granada TV Studio at Albert Dock. It was not in our interests. It was in theirs. The conscious derailment by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority in 2012 of the Atlantic Gateway strategy which would have seen multi-billion pound investments along the Ship Canal land corridor including at Liverpool and Wirral Waters was torpedoed in favour of a focus on city regions and what became the Northern Powerhouse with the cheques signed off in George Osbourne’s Tatton constituency. It sank the prospect of region-wide regeneration in favour of the city to the east. It was not in our interests. It was in theirs. The decision to build two gold-plated HS2 stations in Manchester and Manchester Airport (and none in Liverpool), given the nod in 2013, meant an unnecessary dog-leg and longer commutes between the cities. It was not in our interests. It was in theirs. Not that Joe Anderson would have noticed. He was like a blind man in a room full of alligators. Food for the predators. But the piece de resistance dates back to 2001 and the signing of the hard to believe Manchester-Liverpool Joint Concordat Agreement by the leaders of the two cities under the watchful eyes of the then Deputy Prime Minister, John Prescott and the supposedly neutral North West Development Agency. Inspired by a Salford University academic, the agreement proposed to end our ancient enmity once and for all. As noted in the Independent, the Concordat bluntly concluded that Manchester was the "regional capital" and there is "little sense in Liverpool seeking to challenge that reality". It must have been hard to suppress the sniggers. Whole industry sectors were carved out for non-competition, the kind of ones that generally required office space and high paying skills. Liverpool’s “unique attributes and distinctive economic strengths” won it tourism and culture, and then Manchester, with a belly full of everything else, went after that anyway with its £114m government funded Factory arts venue and it’s Art Council supported Manchester International Festival. Needless to say this sorry document - the Joint Concordat - was not in our interests. It was in theirs. That a Liverpool Council Leader – Lib Dem, Mike Storey, saw fit to sign such a blatant sell-out of his constituents’ futures shows that he was nowhere near as clever as he thought he was. He was played pure and simple. Either that or he had a masochistic streak, though the fact he ended up in the House of Lords suggests he wasn’t the one feeling the pain. The story doesn’t end there of course – the drip, drip, drip of consequence – of capital and talent continuing to haemorrhage away. Companies like Castore, Redx and Biofortuna. The grass definitely greener on the other side.

I can’t condemn Manchester for acting in its own interests. I just want the same for Liverpool. I want us to wake up to our interests. To fight for them and to have the good sense to know when we are being had. To stop being a patsy. To stop playing the fool. Talk that cities don’t need to compete is fitting of the dunce cap and I think we’d all prefer to wear more desirable head gear.

“That a Liverpool Council Leader – Lib Dem, Mike Storey, saw fit to sign such a blatant sell-out of his constituents’ futures shows that he was nowhere near as clever as he thought he was. He was played pure and simple.”

The recent spat between local councillors and developers at Waterloo Dock was a symbol of another fine mess we’ve built for ourselves – another expression of Liverpool’s ability to trip on its own feet. Amongst the general rot and dereliction, we built a complex nest of low aspirations to house not Canada Geese, but local representatives, who like squawking chicks pretended their advocacy of ‘blue space’ was a defence of high aspiration and ‘world-class’ heritage. That phrase again. It was nothing of the kind.

The enraged opposition to the development of what is to any sane person a piece of wasteland was deeply embarrassing to watch. Frustrating attempts to encourage inward investment, councillors cronied up to self-interested NIMBYS who were out to protect their own river views. In doing so, they further entrenched an anti-capitalist, ‘scousers versus the world’ mentality. By pitching local people against ‘greedy developers’ and roping in heritage ‘concerns’, they found a new way to frustrate Liverpool’s aspirations, and in the process convinced some poor sod from the Planning Department to embarrass himself at the appeal. Thankfully on this occasion reason won out and the determined developer won the day. I suspect we’re wiser to their tricks now. The ‘build nothing’ types will find it harder to play their games in the future.

Rabbits were suddenly ‘discovered’ in Bixteth Gardens by campaigners against an office development. Photo by Gavin Allanwood on Unsplash

Even with the Waterloo Dock development getting over the line, there does seem to be a sense of red brick, low-rise defeatism in the city’s modern architectural landscape. Where cities like Manchester and Birmingham go big, Liverpool has managed to shroud its lack of urban aspiration in a thin veil of heritage and ill-informed talk of ‘human scale’. While Manchester and other progressive cities throw up new developments like confetti providing new homes, jobs and office spaces for international companies, Liverpool’s local councillors, like Labour’s Nick Small, shamefully protest against developments such as Pall Mall, a long overdue project to bring Grade A office space to a city that has one of the smallest portfolios of commercial floorspace in the country.

Why did the protesters object? Rabbits. Now I’m all for the protection of wildlife but the former Liverpool Exchange station site is not the setting for Watership Down. I’d much rather see our public institutions looking to attract companies out of rival conurbations and into our own central business district, incentivising them to base in new, large-scale, glass, brick and steel office blocks. But that sounds too much like hard work. I guess it’s much easier to rationalise doing nothing by weaving an almost religious acceptance to it. Building is for other cities, it’s not for us. We have another vision. What is it? Don’t know.

What Liverpool needs desperately is to find leaders in business, politics and the community who are unashamedly ambitious. But what does that ambition look like? Ambition and aspiration for Liverpool should be in the form of a real, tangible plan to re-position the city at the forefront of northern politics and to openly and confidently shun any notion of northern capitals in Manchester. In fact, I would suggest making it a core strategy to pull as much investment, business and talent away from our northern neighbours and London as is humanly possible. Let them know they are in a fight. We Come Not To Play. Liverpool gains next to nothing from ‘collaboration’ with Manchester, never has and never will. If anything, in our naivete we are just helping to reinforce this self-defeating status quo.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.