Recent features

Taylor Town Kitsch, Ersatz Culture and the Art of Forgetting

As Liverpool rolled out the red carpet for Taylor Swift, America's biggest pop star and her hordes of cowboy hat-clad 'Swifties' , the city's culture chiefs congratulated themselves on the global media coverage. 'This is who we are' seemed the message. But in this time of forgetting, John Egan wonders, is kitsch really who we are and what we want to be?

“If we don't know where we are, we don't know who we are,”

Jon Egan

It may seem perverse to even pose this question, especially as Liverpool was only recently judged by Which? as the UK's best large city for a short break by virtue of its “fantastic cultural scene”. But ask it I must. Despite once proudly wearing the title of European Capital of Culture of 2008, is Liverpool really a cultural city? To paraphrase the BBC's celebrated Brains Trust stalwart, C.M Joad, I suppose it all depends on what you mean by culture?

My worry is that Liverpool appears to be operating under an increasingly narrow and debilitating definition of culture, or at least, offering to the world a version of its cultural self that seems weirdly stunted, shallow and ultimately synthetic - something the American art critic and essayist, Clement Greenberg might have characterised as ‘kitsch’. Writing in 1939, Greenberg's essay 'The Avant-Garde and Kitsch' defined the latter as embracing popular commercial culture including Hollywood movies, pulp fiction and Tin Pan Alley music. He saw kitsch as a product of rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, which created a new market for “ersatz culture destined for those who, insensible to the values of genuine culture, are hungry nevertheless for the diversion that only culture of some sort can provide.” These mass-produced consumer artifacts, by definition formulaic and for-profit, had driven out "folk art" and authentic popular culture replacing it with what were essentially commodities.

One does not have to be a Marxist (Greenberg was) or a cultural snob (he was possibly one of those as well) to be slightly worried that Liverpool's cultural brand is beginning to lean too heavily in the direction of the kitsch and the hyper-commercial. It was a concern, first articulated in the run-up to Liverpool's hosting of Eurovision last year by the Daily Telegraph’s Chris Moss, “Liverpool has chosen Eurovision kitsch over protecting its history and heritage”, and explored further in my Liverpolitan article, “Liverpool's Imperfect Pitch”. A feeling that has only been exacerbated by the recent Taylor Town phenomenon.

For the somehow blissfully unaware, Taylor Town was a “fun-filled” council-funded initiative to transform the city of Liverpool into a Taylor Swift “playground” designed to offer a “proper scouse welcome” to the American pop star and her legion of fans before three sell-out shows at the Anfield stadium. This included commissioning eleven art installations each symbolising one of the artist’s 11 albums – everything from a moss-covered grand piano to a snake and skull-clad golden throne – all designed to be instantly instagrammable.

A golden throne inspired by Swift's 'Reputation' era forms part of Liverpool's Taylor Town trail conveniently located for lunch options. Image: Visit Liverpool.

Sure, Liverpool wasn't the only port of call on Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour to dress-up for the Swifties, but wasn't there something about the hype and hullabaloo that went beyond due recognition and celebration of a major musical event?

My queasiness about Liverpool's Taylor Town re-brand is more than mere snobbishness, or a patronising disdain for popular culture. Our willingness to conflate the city’s very identity with the persona of the American pop icon carries worrying echoes of Councillor Harry Doyle's “perfect fit” mantra between Liverpool and Eurovision. This is somehow more than just a smart bit of opportunistic marketing; it implies some deeper and integral affinity. Public pronouncements by Doyle and Claire McColgan, invoking the spirit of Eurovision, suggested Swift's visitation was seen as an epiphanic moment of self-realisation. In a spirit of almost quasi-mystical reverie, Clare McColgan explained; “the world can be a very dark place and in Liverpool, it’s light.”

If Taylor Swift has somehow become the embodiment of our cultural identity and ambition, what exactly have we become? The American cultural writer and scholar, Louis Menand observed, “in the 1950s the United States exported a mass market commercial product to Europe [rock n roll]. In the 1960s, it got back a hip and smart popular art form.” He is, of course referencing The Beatles and sadly it seems that we are once again being sold short on this cultural transaction.

“Liverpool's cultural brand is beginning to lean too heavily in the direction of the kitsch and the hyper-commercial.”

Despite Doyle's claim that her arrival “was very much in the spirit of the city's musical history”, Taylor Swift is not The Beatles. In the words of the Canadian feminist writer and blogger, Meghan Murphy she “will be forgotten in 20 years, which cannot be said for Janis Joplin, Carly Simon, Etta James, Leslie Gore, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Whitney Houston, Aretha Franklin, or Tina Turner... And none of those women made it on account of being beautiful or having a string of celebrity boyfriends. Certainly, they will not be remembered for their ability to command the hysterical attention of legions of young fans. They were just very good.”

Swift may be a global superstar, a role model and a performer with genuinely admirable philanthropic and compassionate sensibilities, but she is also according to Murphy, bland, manufactured and ephemeral - the literal embodiment of kitsch. Merely staging one of her concerts does not boost our cultural capital or say anything true or meaningful about who we are. For Harry Doyle, the sheer scale of global media coverage is its own justification. “So far, our city has been featured on just about every media outlet worldwide, including the Today Show in the US”, he excitedly claimed, as if a simple volumetric calculation was enough to establish cultural prestige.

Making “the city part of the show” to quote Claire McColgan, and building a civic and cultural brand by staging big events, was the thesis underpinning the city's post-Capital of Culture prospectus, The Liverpool Plan. Describing Liverpool itself as “The Great Stage” it prefigured a reality that those concerned about the condition and accessibility of our waterfront and parks are beginning to realise has troubling consequences. There may well be a perfectly credible argument for hosting large scale events and showcasing the city's architectural and heritage assets, but this is no substitute for what cities, once saw as their responsibility to promote and nurture culture in its widest sense.

So, do we need a different yardstick for what makes a cultural city? If Liverpool wasn't a cultural city, or had not been a cultural city, then I would in all probability not be here. When my father accepted a job in Liverpool it was intended as a stepping-stone to Dublin, the city where my parents had met and always aspired to settle down. It was the discovery that Liverpool possessed everything that Dublin promised, that persuaded them to put down roots in a place that satisfied all their cultural appetites. This was a time when both UK and international opera and ballet companies regularly visited our city, when cutting-edge theatrical productions had their pre-West End runs in the city's array of thriving theatres. It was also the time when Sam Wanamaker was transforming the late lamented New Shakespeare Theatre into what The Guardian described as “one of the first multi-strand art centres in Europe” - a venue that was open 12 hours a day, staged contemporary theatre as well as films, lectures, jazz concerts and art exhibitions and put on “free shows for workers every Wednesday afternoon.”

“Taylor Swift may be a global superstar with admirable philanthropic sensibilities, but she is also bland, manufactured and ephemeral - the literal embodiment of kitsch.”

Moss-covered piano inspired by Swift's 'Folklore' era, one of eleven exhibits that made up the Liverpool Taylor Town trail. Image: Visit Liverpool

From the 19th century onwards, culture was embedded in Liverpool's civic project, the city’s self-image being proudly cosmopolitan rather than prosaically provincial. “High Art” might not be the exclusive criterion for what constitutes a cultural city, but it was, for a time at least, integral to Liverpool’s claim to that status. Now it would appear that culture has no intrinsic value other than as a means to an end. Taylor Town was, in Doyle's words, “much needed PR the city needs to attract investment and visitors.”

The irony is that a positioning or investment strategy focused on big events and blitz publicity is quite probably a less effective strategy than one focused on stimulating cultural quality and diversity of offer. Events may deliver a short-term boost to the tourism and hospitality sector, but smart cities understand that the depth, quality and originality of their cultural offer is what draws investment and attracts and retains people. Once again, it might be instructive to look to our regional neighbour, Manchester for inspiration. The Manchester International Festival (MIF) not only reveals a city that, unlike the organisers of LIMF (Liverpool International Music Festival), understands the meaning of the word "international," but is also a masterclass in intelligent place marketing. MIFs inspired, left-field commissions and collaborations are deftly configured to spell out one simple message - “Hey, we're just like London.” In other words, we're the sort of city that's ready-made for banished BBC executives, relocating corporates, boho entrepreneurs or the English National Opera (ENO). Manchester benchmarks its cultural strategy against cities like Barcelona and Montreal, disruptor second cities harbouring global ambitions.

There was a sad inevitability about the ENO relocation to Manchester after Liverpool had failed to make it beyond the shortlist. Liverpool's city leaders offered a flimsy defence of their laissez-faire approach to pitching - that this was a process-driven exercise where lobbying and advocacy were superfluous and potentially counterproductive. Yet as a well-placed Manchester source explained, “Yes, it was process-driven, but the timing worked for us, coming [so soon] after the Chanel Show which secured exactly the right kind of media coverage.” (Note - quality not quantity) “But the key was the availability of a versatile and conveniently available performance venue designed by Rem Koolhaas, that didn't really have a defined function or use-strategy.” The commissioning of The Factory / Aviva Studios was an audacious exercise in the ‘build it and they will come’ approach to urban regeneration, and proof that Manchester, like the Biblical wise virgins, is a city always primed with a trimmed wick and plentiful supply of oil.

Probably, a more significant consideration was the perception that Manchester had an audience for opera whilst Liverpool possibly did not. One of the most depressing episodes in my professional life came during a discussion with Liverpool's big cultural players whilst working on ResPublica's HS2 for Liverpool advocacy project. A prominent, though now departed, head of a prestigious cultural institution, lamented that they would love to deliver a more ambitious programme (as they had in 2008) if only they could “attract an audience from Manchester.” Yet as the success of Ralph Fiennes' Macbeth production at the Depot venue proved last year, this comment is as ill-informed as it is profoundly dispiriting.

“From the two fake Caverns and tat memorabilia of Matthew Street to the anodyne mediocrity of “The Beatles Story”, we are now celebrating what was once subversive popular art in the guise of the mass-produced ersatz culture to which it was once the antidote.”

The Beatles Story: A fake grave cast in authentic-looking granite to a fictitious character Paul McCartney claims he ‘made up’. Could this be any more ersatz or is it just ‘meta’?

Photo: Paul Bryan

For all its sophistication and legacy of transformed cultural assets, there is still a whiff of utilitarianism about Manchester's approach, and a view of culture as primarily an instrument of economic regeneration. Hence an emerging new strategy with a greater emphasis on what they term “cultural democracy” with a more equal and diverse distribution of cultural resources and opportunities.

Notwithstanding the undoubted quality of our visual arts assets and collections, Liverpool's performing arts offer is now sadly diminished and, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra excepted, is hardly commensurate with what you’d expect of an aspiring cultural city. If Liverpool is to entertain genuine claims to that title, then maybe we need another definition that isn't founded merely on physical assets or an eye-catching events programme?

For American essayist and poet, Wendell Berry “culture is what happens, when the same people, live in the same place for a long time.” For Berry “same people” doesn't entail ethnic homogeneity. His own Appalachian culture is a heady brew of English, Scots Irish, Cherokee and African influences that even a fledgling Taylor Swift, once wanted to get a piece of. His definition is closer to what Clement Greenberg saw as the antidote to kitsch - “folk art”. This is culture with roots, with an organic and intimate connection to place, with a character, accent and disposition that are distinctive and inimitable. By this yardstick, cultural cities are not just places that stage culture or boast a wealth of cultural assets, they also cultivate and disseminate it. It is in this sense that Liverpool can perhaps advance its most convincing claim to be a cultural city.

Liverpool's culture is as much an ambience and attitude as it is an archive of expressions and artefacts. It emerges in creative convulsions that emanate from a deep geology, a substratum of shared stories and memories. In the 1960s, it was Merseybeat, the poetry of McGough, Patten and Henri, the forgotten genius of sculptor, Arthur Dooley, and the phantasmagorical humour of Ken Dodd. (Are the jam butty mines of Knotty Ash just charming whimsy or, like Williamson's Tunnels, secret portals into the arcane depths of Liverpool's collective unconscious?). The early noughties, as the city began to dream of becoming a European Capital of Culture, happily coincided with another creative spasm, as Fiona Banner was shortlisted for the Turner Prize, Paul Farley won the Whitbread Poetry Prize, Delta Sonic Records were trailblazing Liverpool's third musical wave, and Alex Cox was back in town collaborating with Frank Cottrell Boyce on their, as yet unrecognised masterpiece, Revenger's Tragedy.

“Memory is the alchemy that transmutes the base metal of the everyday into the life-enhancing elixir of an authentic culture. But we live in a time of forgetting, of uprootedness, fracture and disinheritance, and even a city famed, and often derided, for its obsessive nostalgia, is not immune from this pervasive fixation with the immediate, the superficial and the kitsch.”

It's not just the social realist triumvirate of Bleasdale, Russell and McGovern whose writings are moored in the anchorage of their home port city. For novelists like Beryl Bainbridge, Nicholas Monsarrat and Malcolm Lowry, Liverpool looms and lurks in the shadows of their fiction even as a point of departure or an unspoken absence. For two contemporary Liverpool writers, the city is an object of almost erotic communion. Musician Paul Simpson's gorgeously poetic memoir, Revolutionary Spirit, and Jeff Young's Ghost Town are immersions in secret treasuries of memory and miracle. Young is Liverpool's cartographer of the marvellous, tour guide to our fevered Dreamtime for whom Liverpool “is the haunted place of remembering.”

Memory is the alchemy that binds past and present, that invisibly entwines the living with the dead. It's what transmutes the base metal of the everyday into the life-enhancing elixir of an authentic culture. But we live in a time of forgetting, of uprootedness, fracture and disinheritance, and even a city famed, and often derided, for its obsessive nostalgia, is not immune from this pervasive fixation with the immediate, the superficial and the kitsch. In a blisteringly brilliant essay in The Post, Laurence Thompson poses the question, why is Liverpool unwilling or unable to recognise the creative achievement of filmmaker and “great visual poet of remembrance,” Terence Davies, and his seminal trilogy Distant Voices, Still Lives?

“That such an impressive work of art came both from and was about Liverpool seems worthy of commemoration. Yet it’s impossible to imagine the Royal Court commissioning a major contemporary playwright to adapt a stage revival of Distant Voices, Still Lives... I’m not advocating Davies’s memory falling into the hands of the usual custodians of Liverpool’s heritage. What’s the point in putting up a blue plaque commemorating the original Eric’s when the current Eric’s is so unbelievably shite? But the choice between amnesia and kitsch must be a false dichotomy.”

The French seem more inclined to remember the seminal films of Terence Davies, than Liverpool, the city of his own birth. A retrospective held at the Paris Pompidou Centre in March 2024.

Alas, it seems we are increasingly opting for kitsch, not just in terms of our desire to bask in the reflected aura of Eurovision and Taylor Swift, but also in how we package and commodify our own cultural legacy. From the two fake Caverns and tat memorabilia of Matthew Street to the anodyne mediocrity of “The Beatles Story”, we are now celebrating what was once subversive popular art in the guise of the mass-produced ersatz culture to which it was once the antidote. Kitsch's suffocating omnipresence is a soporific that dulls memory and transports us into its own featureless geography. “If we don't know where we are, we don't know who we are,” explains Wendell Berry. For Berry, culture, identity and place are a sacred trinity without which human society withers and sinks into the shallow abyss that G.K. Chesterton termed the “flat wilderness of standardisation.” A time of forgetting is also a time of false belonging. Polarised politics, bitter culture wars and horrifying street violence are in different ways a thrashing around in search of connections to something enduring and meaningful in the bewildering Babel of post-modernity.

Consigning an artist of Terence Davies' stature to the margins of oblivion is sinful enough, but it is emblematic of a deeper estrangement and disconnection. A city that squanders its World Heritage Status, that's indifferent to its own cultural history and cheerfully embraces an architectural aesthetic of shabby and soulless mediocrity, is forsaking its very identity. In the spirit of Louis Aragon's Le Paysan de Paris, Jeff Young chronicles Liverpool’s neglectful disregard for the overlooked, the curious and the idiosyncratic, for the magnetically charged spaces and landmarks, like the sadly demolished Futurist cinema, that are the coordinates of our collective remembering. Ghost Town is an odyssey in search of a submerged city, drowning under the dead weight of the bland and the banal.

“The magic is leaching from the city, the shadows and alleyways are emptying, and so we walk through wastelands where the magic used to be, we gather autumn leaves from gutters and dirt from the rubble of demolished sacred places.”

Identity and culture are rooted in the original, the distinctive and the unwonted, in things that should be reverenced, not wilfully expended.

At the conclusion of his Gerard Manley Hopkins Lecture at Hope University earlier this year, I asked Jeff, how do we breach the chasm that seems to separate those who love the city, from those who govern it? There isn't a simple answer, but it must surely involve some thoughtful consideration of what it means to be a cultural city. Culture in its authentic form, is salvific. Being connected to a place, its story and to each other is to fulfil one of our most basic human yearnings.

For now, at least, the circus has left town. Eurovision and Taylor Swift have moved on to the next “destination.” But if we want to get in touch with our culture, we need to see through the eyes of poets and artists like Jeff Young and Terence Davies, to look beyond the empty stage for something part-buried and only half remembered - the immeasurable richness of a cultural city.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Main Image: Paul Bryan

Public Art is Dead. Long Live Culture.

Liverpool has a complex relationship with its Art. Priding itself on its cultural credentials and home to the Liverpool Biennial art exhibition, yet its institutions tend to measure Art’s value in the spreadsheet metrics of the philistine. As our publicly commissioned pieces become ever more disposable, sanitised and inoffensive, art historian Ed Williams asks whether Liverpool is the place where art comes to die?

Ed Williams

Fifteen years have elapsed since Liverpool was honoured with the title European Capital of Culture, and with the help of constant repetition, the city’s status as a ‘Cultural City’ has been cemented within the popular consciousness, at least locally, if not always universally. But what, if anything, does this accolade mean today? And how do we stop it being just a meaningless marketing label, presuming it was ever more than that to start off with?

Culture, or at least a certain type of culture, is like universal health care and compulsory education often viewed as an indisputable social good – a life enhancer that with official state sanction became a defining feature of Britain’s Post-War project to improve the lives of its population. But culture is an elusive quarry - challenging to define, let alone to quantify within a framework of metrics. Unlike healthcare, culture does not ‘treat’ or ‘heal’ in a way that lends itself to spreadsheet evaluation. Nevertheless, a consensus of bien pensantism has coalesced around the importance of culture, invariably focusing less on its intrinsic and frustratingly wishy-washy, hard to define benefits and more on its ability to generate economic returns – something our civic leaders and purse-string holders can feel confident about putting on a press release. As a result, we’ve all become familiar with hearing how some new cultural initiative will add value to the local economy increase visitor spend, improve hotel occupancy rates, and create and sustain those all-important X number of jobs. We understand why these arguments predominate, but accusations of philistinism aside, the true purpose of culture seems to lie elsewhere.

These statistics, often quoted as culture’s most manifest benefit, highlight a fundamental point. In Britain’s post-industrial society, culture is increasingly what economic output looks like. The service sector is the prime employer, and culture is a branch of this sector. That’s why the leaders of our cultural institutions increasingly seem to resemble business men and women rather than merely champions of the arts. Or at least, they certainly have to moderate their artistic passions behind drier, more utilitarian language. The managers of a museum or art gallery may have more in common with that of a hotel or restaurant than is perhaps initially recognised, being equally concerned as they are with customer satisfaction, visitor throughput and money spent.

“A consensus of bien pensantism has coalesced around the importance of culture, focusing less on its intrinsic and frustratingly wishy-washy, hard to define benefits and more on its ability to generate economic returns.”

What one could colloquially call the ‘Cultural Economy’ argument may then explain the need among those, both in government and in the arts, to continually re-iterate the significance of Liverpool’s cultural status. After all, if we weren’t so economically desperate, perhaps there would be more willingness to talk about culture in its own terms and less need to worry about the financial side-benefits? In the absence of much else to shout about, continuously asserting the city’s cultural status becomes a proxy for saying we’re still here, we’re still relevant, we still have a future. It’s also jolly useful for any politicians keen to show they are making good decisions in a challenging environment.

Despite this, the inquisitive might well ask if this is all there is to ‘Culture? Is there anything beyond the reductivism of the bottom line? And if there is, how do we gauge it?

Beyond hosting prestigious events such as the recent Eurovision Song Contest Final, more recent efforts to assert Liverpool’s cultural status appear to focus on the commissioning of works of public art, such as Alicja Biala’s Merseyside Totemy (2022) and, more recently, those unveiled as part of this year’s Liverpool Biennial, including Rudy Loewe’s The Reckoning (2023) and Nicholas Galanin’s Threat Return (2023). These totemic pieces, no pun intended, now seemingly serve as cultural barometers through which our city’s cultural status appears to be discerned. Behold people of Liverpool, this is culture!

Black Power. Exploring ‘hot’ issues in inoffensive ways. Rudy Loewe, The Reckoning, 2023. Photograph by Rob Battersby, courtesy of Liverpool Biennial.

The result of this approach is an ever-increasing amount of public art on display. Whilst prima facie positive, the fact remains that the burgeoning number of works is so great, it is becoming an increasing challenge to maintain an accurate count; and to attend to their continued preservation and maintenance. But then maintenance no longer seems to be part of the brief.

Instead, in an Age of Austerity, public art is commissioned, paid for, put on display for a short time, and there the liability typically ends, with the item often all too swiftly packed up and removed to some mysterious warehouse/bonfire in the sky as if it never really existed – outside of a few pictures on the internet. This is Art transformed into fast moving consumer goods, less a vision for the ages cast in marble and more a plastic bag flapping in the wind. This hard-nosed economic reality may well explain why so many of the recent commissions have only a temporary status within the city. For example, as things stand, Alicja Biala’s Merseyside Totemy will be removed at some point in 2024.

Could this new approach to a work’s lifespan be a consequence of the fact that older pieces have been left to their own devices? Betty Woodman’s Liverpool Fountain (2016) looks to be in a forlorn state, with water flowing only occasionally. Stephen Broadbent’s beautiful and powerful Reconciliation (1) (1990) is blighted by the twin plagues of graffiti and adhesive stickers.

“In an Age of Austerity, public art is all too swiftly packed up and removed to some mysterious warehouse/bonfire in the sky as if it never really existed. This is Art transformed into fast moving consumer goods, less a vision for the ages cast in marble and more a plastic bag flapping in the wind.”

A cynic might surmise that this is an attempt to manifest ‘culture on the cheap’, far removed from the initial spirit with which Public Art was originally conceived in the immediate Post-War period. These works from the 1950s and early 1960s, originating at a time of greater optimism, represented egalitarian attempts to bring art to the wider public, away from the confining and often restrictive environs of museums and galleries. Typically, it was art designed to uplift the spirits. This was how the work of Moore, Hepworth, Epstein and Paolozzi, amongst others, became better known and appreciated by the non-gallery attending public. It was this zeitgeist of civic ambition and new hope that Jacob Epstein sought to depict in his iconic Liverpool Resurgent (1956) which still stands proudly defiant above the main entrance of the former Lewis’ department store. Later works such as Richard Huws’ cheerful kinetic sculpture, the Piazza Fountain(1967), more commonly known as the ‘Bucket Fountain’, were attempts to create a sense of place in an otherwise rather anonymous space. This second generation of works, beginning in the late 1960s, were also conceived as catalysts for development, particularly during the economic dark days of the 1980s and 1990s. They may be considered as examples of the role of public art in regenerating neighbourhoods and communities. Superlative pieces such as Charlotte Meyer’s Sea Circle (1984) and Tony Cragg’s Raleigh (1986) are stand out examples of British Postmodern sculpture at its best.

Cryptic. Visualising climate data to make it ‘accessible’. But can you trigger a conversation if no-one knows what you are talking about? Alicja Biala, Merseyside Totemy, 2022. Commissioned by Liverpool Biennial & Liverpool BID Company. Photograph: Ed Williams.

In more recent years, works have been commissioned by various bodies, including the Liverpool Biennial and Liverpool BID Company. Such is the abundance of these new works it would appear each year heralds at least one new unveiling. But is this merely art for art’s sake? Or does this reflect a wider desire to decorate the city with public art and thereby turn the urban environment into an open air gallery of temporary works? Whatever the motivation, the result appears to be a confusing array of pieces, revealed with some fanfare and then seemingly allowed to decay through neglect or indifference. The casual observer could be excused for concluding that Liverpool is a city where public art comes to die, discarded and left as litter like so many broken domestic appliances. Is this seeming lack of care evidence of a wider malaise within Liverpool’s cultural sector? Is it a failure to fully appreciate that a cultural legacy necessitates ‘after care’? Or does it merely reflect a changing view of art as temporary and disposable? Perhaps we no longer feel able to commit to ideas in the same way – our art like our views increasingly contingent and subject to new interpretations. Are older works, such as Carlos Cruz-Diez’ Induction Chromatique a Double Frequence pour L’Edmund Gardner Ship (2014) – that remarkable dazzle ship - now mere historic footnotes? Having been re-painted, all that remains of Carlos’ work is a small weather beaten placard. I can’t help wondering whether our seemingly endless obsession with the ever elusive avant garde, makes consideration of the established, the old and the familiar now anathema?

This focus on the temporary and the cheap may be the avowed intention of those who commission Liverpool’s contemporary public art, but a critical eye cast over recent works would conclude that they offer little to truly spark the imagination. These pieces provide not the ‘shock of the new’, but rather a dull blandness, resulting in a series of indifferent works which seemingly seek to please only the passing tourist and the selfie hunter. Consider for a moment, Ugo’s Liverpool Mountain, a vertically stacked tower of candy coloured stone blocks placed prominently at the Albert Dock. Whilst initially amusing, and you could argue eye-catching against the uniformity of the dock’s red-brick warehouses, it hardly moves one to further contemplation. But perhaps more importantly in a clear nod to modern sensibilities, neither does it offend anyone. This is Art as Entertainment. Seen, consumed and then forgotten.

“The dissonance between the pretensions of the explanatory labels and the works themselves is a gaping chasm. Alicja Biala’s sculptures are supposedly an attempt to visualise climate data, but you can’t spark a conversation if no-one knows what you are talking about.”

Even commissions which claim to have a more intellectually challenging agenda often fall short. The current Liverpool Biennial includes pieces which address hot button concerns such as race relations, social inequality and climate change, but these works only explore these issues in the most convoluted or inoffensive ways, often leaving the viewer unengaged, bemused or, at best, just happy to have themselves photographed next to a decorative work. The dissonance between the pretensions of the explanatory labels and the works themselves is a gaping chasm. Alicja Biala’s 2022 piece, Merseyside Totemy is a case in point. Only by reading the artist’s explanation or some earnest review in the nationals could you guess at the message. These sculptures are supposedly an attempt to visualise climate data, which we are told can often seem too ‘academic and theoretical’. But au contraire – they are the very example of clarity compared to these cryptic albeit pretty land buoys. You can’t spark a conversation if no-one knows what you are talking about.

Eleng Luluan’s, Ngialibalibade to the Lost Myth, 2023 is highly decorative but does it challenge the mind? Photograph by Ed Williams.

Rudy Loewe, The Reckoning, 2023 is another example of an attempt to make a serious point in an inoffensive way. Rudy’s original work was a far more powerful meditation on the injustices of British colonialism and a celebration of the 1970 Black Power Trinidadian Revolution. Yet this Biennial piece with its pink, orange and cyan stilt walkers just looks ‘funny’. But perhaps the award for the least engaging work should go to Eleng Luluan with her Ngialibalibade to the Lost Myth, 2023. According to the official spiel, ‘Ngialibalibade’ describes ‘the growth of life, the transformation of the soul, the change in nature, the rapid development of technology, the noticeable changes in life, or the subtle ones hiding in our hearts.’ Make of that what you will. It’s claimed the work has something to do with landslides in Taiwan and their power to upend ‘culture’. Though why culture rather than life should be emphasised is curious. Either way, its pottery jar made of fishing nets is remarkable more for its decorative qualities than its ability to provoke meditation on humanity’s relationship with nature. Still, at least it helps to mitigate the torpor elicited by the architecture of Princess Dock.

Surely culture must mean more than this? If the power of art stems from its ability to move, provoke or encourage us, then it must do more than merely act as decoration. Does this malign trend towards the banal and the superficial herald the craven surrender of those in leadership roles within the city’s cultural institutions to eliminate the alleged activism of art? Is this a reaction to the supposed ‘culture wars’ so obsessively reported on by the political right? Or can public art now only ever be commissioned if it is considered ‘safe’, inoffensive, and non-challenging? A small number of indifferent pieces may be forgiven, but the sheer abundance of such bland works seems anathema to the professed aims of public art.

“Perhaps we no longer feel able to commit to ideas in the same way – our art like our views increasingly contingent and subject to new interpretations.”

Forlorn. Betty Woodman, Liverpool Fountain, 2016. “The casual observer could be excused for concluding that Liverpool is a city where public art comes to die.” Photograph by Ed Williams.

I challenge those that cling to the illusion, with respect to public art, that ‘more is more’ in perpetuating Liverpool’s status as a ‘Cultural City’. Just as the European Union’s ever expanding list of cultural capitals – now an increasingly unexclusive club of 78 - tends to devalue the idea of the exceptional, so Liverpool must pay greater heed to what is valuable or risk swamping the quality it does possess in a sea of disposable superficiality. Or worse, lose its ability altogether to distinguish between what is good and what is not. If it is to be more than just an empty slogan, being a cultural capital should act as a rallying call to better appreciate the truly wonderful works we have and to consider commissioning pieces which truly reflect the dynamic power of art.

This is not an argument for ‘less is more’ – rather an entreaty to maintain the important works of public art that we already possess and to focus new commissions on truly ground breaking and lasting works for the people of Liverpool. This should be the real legacy of our City of Culture status.

Ed Williams is an Academic Art Historian who works for TATE Liverpool in the Visitor Experience team. He is a member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and he teaches the History of Art at the University of Liverpool.

Ed is currently running a 5-week course at the University of Liverpool entitled 'How to Understand Art' starting in October 2023. For more details on enrolment click here.

Main image: Ugo Rondinone, Liverpool Mountain (2018). Photograph by Ed Williams.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Eurovision 2023: Liverpool’s Imperfect Pitch

When Liverpool won the right to host Eurovision 2023 on behalf of war-torn Ukraine, most people in the city celebrated. With its reputation for music and for fun nights out, allied to its compassionate heart, the city was seen as the perfect fit in difficult times. But some have warned that in mistaking kitsch for cool Liverpool risks reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of its cultural brand. Jon Egan wonders how we can subvert expectations to deliver on the European Song Contest’s higher purpose.

Jon Egan

Amidst the near-universal jubilation at Liverpool’s successful bid to stage Eurovision, I struggled to suppress an almost inchoate feeling of dissident cynicism. Is the European Capital of Culture now pitching its future identity on an ambition to be the European Capital of Light Entertainment?

Liverpool is a perfect fit for Eurovision we are told by the bid’s architects and cheerleaders, though this natural synergy with an event that was until very recently derided as a festival of musical mediocrity is at the very least an arguable proposition. No disrespect to Sonia (creditable second) and Jemini (nul points), but they are rarely name-checked when the city intones the sacred litany of its popular music icons. As travel writer and destination expert, Chris Moss opined in his recent Daily Telegraph article; “From Echo and the Bunnymen to The Farm, from The Mighty Wah to The Lightning Seeds, pop and rock culture in Liverpool has always been anti-establishment, iconoclastic and often disdainful of national media-driven circuses."

I’m old enough to associate the Eurovision Song Contest (as it was called once upon a time) with Katie Boyle, a BBC stalwart and actress whose deft professionalism and elegant gentility made her a perfect fit as TV host for an earlier incarnation of the continent’s festival of song.

I’m not quite old enough, however, to remember, what is now my favourite ever Eurovision-winning performance, France Gall’s weirdly off-key rendition of Serge Gainsbourg’s ironic masterpiece, Poupee de Cire, Poupee de Son. Yes, there was irony at Eurovision long before Conchita Wurst or the knock-about stage-Irish buffoonery of the late Sir Terry Wogan.

Eurovision’s durability is doubtless its capacity to adapt to the changing mores of social convention and popular culture, not to mention the seismic disruptions to the boundaries and very identities of its competing nations. Which of course, takes us to 2023 and a Eurovision overshadowed by the tragedy of war in Ukraine. So it’s time for me to swallow my cynicism and recognise that this Eurovision is more than a celebration of blissful superficiality. Eurovision, which was conceived as an event to help bring a war-ravaged continent back together, has rediscovered a higher purpose and it’s up to us to deliver it.

There are already some encouraging signs. Claire McColgan and her team are planning an events programme that will celebrate Ukrainian culture in its many guises and remind the watching millions why this is happening here and not there. Liverpool’s Cabinet Member for Culture, Councillor Harry Doyle, told a gathering of stakeholders that he’s open to ideas about how the city can derive the maximum benefit and the most enduring legacy from next year’s Eurovision. So, if Harry wants my two penn’orth worth, here goes.

Whilst researching an article for the Daily Post sometime in the run-up to the European Capital of Culture, I asked David Chapple, a former Saatchi & Saatchi creative and regular visitor to the city, how he would market Liverpool. His answer was stark and challenging -“Stop telling people what they already know, surprise them!” I’m not sure that we have ever managed to live up to David’s exhortation. As Chris Moss warns, there is a danger that by claiming a perfect fit with an event that “mistakes kitsch for cool” we may simply be reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of Liverpool’s cultural brand. Moss, born and bred in neighbouring St Helens, believes that a city that should be the UK's foremost cultural destination is committing another branding "blunder" (having tossed away its World Heritage Status) by claiming an almost umbilical affinity with what he provocatively dismisses as a "naff, brainless extravaganza."

Moss's rhetoric may be extravagant, but there is more than a kernel of truth in the proposition that we have consistently failed to articulate and market the breadth and quality of our cultural offer. Ensuring Eurovision simply doesn't serve to reinforce a constraining stereotype, has to be a guiding imperative.

“There is a danger that by claiming a perfect fit with an event that “mistakes kitsch for cool” we may simply be reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of Liverpool’s cultural brand.”

So rather than being the perfect fit, let’s set out to design an imperfect fit. Let’s confound expectations, stretch the envelope and deliver a gathering that offers more than the “glitter and sparkle” that Doyle describes as the essence of Eurovision, but also explores what he terms (somewhat vaguely) “the added layer of Europe.”

I’m certain that Harry, Claire and their team are sincerely committed to ensuring Liverpool’s Eurovision acknowledges the wider European and specific Ukrainian context, although the confectionary metaphor suggests an application of icing rather than an especially bespoke cake mix. Surely now more than ever the “added layer” is the essence.

Returning to David Chapple and his urgings to surprise, the challenge to Liverpool would be how do we stage and wrap Eurovision in a way that confounds stereotypical perceptions of the city, that expands and subverts expectations while revealing a facet of unsuspected seriousness and cultural depth? Given the unique circumstances of this gathering, it seems like an appropriate juxtaposition to pitch the exuberant excess of Eurovision with a broader conversation and cultural exploration of the event's unsettling backdrop.

Notwithstanding Joanne Anderson’s excusable hyperbole that “the eyes of the world will be on Liverpool,” Eurovision 2023 will attract enormous numbers of visitors and serious levels of media attention. Liverpool needs to embrace the opportunity, and the responsibility, to do more than simply host Europe’s ultimate carnival of camp.

Are there media partners with whom we could convene a Eurovision of Ideas - a virtual or even physical gathering of thinkers, policy-makers and artists from Ukraine, the UK and Europe to explore how the shattering reality of yet another European war can help us to forge a deeper and more durable sense of solidarity and a shared future?

Is there space to stage an expo for Ukrainian businesses including their burgeoning technology sector, to help them forge new contacts and explore new markets?

For Ukraine, Eurovision has become a symbolic staging post in a journey from isolation and the cultural suffocation of the Soviet era. This war is a painful and bloody episode within the struggle for a new cultural and economic relationship with its estranged continent. So, how do we ensure that the celebration of Ukrainian culture proposed by Claire McColgan is sufficiently resourced to be immersive and integral and not merely a quaint window dressing for the main event? Culture Liverpool is bidding for funds to deliver a European-themed cultural programme, but an email to cultural organisations inviting bids was hastily withdrawn in the absence of any definite funding commitment from Arts Council England. These are early days, but this is not a positive omen.

In a recent conversation with me, journalist and commentator, Liam Fogarty speculated that if Manchester or Glasgow were staging this Eurovision, the scale of ambition might be greater and the prospecting for partners, funders and co-creators more lateral and imaginative. He is perhaps not alone in that thought. For the first time in nearly two decades, we have been successful in a major bidding competition, but what happens when the circus leaves town? What's our pitch to ensure a positive legacy and how do we create this event in a way that shows a previously unsuspected vista of a more interesting and multi-faceted city?

This is a huge opportunity to redress the imbalance of cultural investment towards London (and even Manchester) by demanding the resources to give a platform to the diversity of a resurgent Ukrainian culture, emerging from what contemporary poet, Lyuba Yakimchuk has described as a “war of decolonisation.” At the end of the day, we’re standing in for the place that would, but for the obscene brutality of Putin’s invasion, be hosting this event. So, let’s stretch every sinew and apply every creative impulse to celebrate the identity of a nation that a deranged tyrant is seeking to wipe off the face of the map.

And of course, we already have a connection and relationship with a Ukrainian city dating back to the early 1950s when Odesa was in the Soviet Union. In truth, Liverpool’s twinning relationship with the Black Sea port had become a largely hollow civic anachronism - a relationship long since packed away in the lumber room of municipal memorabilia. Until now, the cultural highlight of the twinning relationship was an impromptu concert by Gerry Marsden on the Potemkin Steps when the Merseybeat legend led an aid convoy after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

“For the first time in nearly two decades, we have been successful in a major bidding competition, but what happens when the circus leaves town?”

For Odesa, threatened with invasion and subject to merciless missile strikes, friendship and solidarity have acquired a new and vivid resonance. Steve Rotheram's ambition to make Eurovision Odesa’s “event as much as our own” is generous and laudable but it will only be honoured by a substantial financial and imaginative investment and genuinely collaborative curation.

Without prescribing what a co-created cultural programme might look like, there is massive scope for stunning and surprising collaborations. One of the many intriguing (and sadly unrealised) ideas championed by the much-maligned Robyn Archer, whose brief tenure as Creative Director for Capital of Culture 2008 marginally exceeded Liz Truss’s occupancy of 10 Downing Street, was to stage performances by the Dutch National Opera in the semi-dilapidated grandeur of Liverpool Olympia. Notwithstanding Liverpool’s uncharacteristic failure to extend our famed hospitality to the soon-to-be homeless English National Opera, we could perhaps invite Odesa’s renowned opera company to be part of our Eurovision cultural celebration in their sister city. Whether at the Empire, Olympia (or even my long cherished dream to stage opera in the epic setting of St Andrews Gardens aka the Bullring), we could at the very least promise them a performance that would not be interrupted by air raid sirens or the rumble of distant explosions.

Sharing the Eurovision limelight with Odesa must be the beginning of a longer-term commitment to work with a city still under daily Russian bombardment. Beyond cultural and humanitarian co-operation, there may be a myriad of ways in which we can assist with trade and reconstruction. Even before the damage inflicted by Russian missile and bombing strikes, Odesa's Soviet-era port infrastructure was in dire need of investment and modernisation. Through a concordat for economic co-operation between the two cities, Liverpool should be using the exposure of Eurovision to gather together and broker the expertise and potential investment partners to help Odesa recover from the trauma and devastation of the present conflict.

All this may seem too ambitious, unrealistic or even unnecessary. At the end of the day, all that’s expected of us is that we put on a show, manage the organisation with reasonable efficiency and make an appropriate gesture to recognise the special circumstances of this Eurovision.

Maximising the opportunity and legacy is an undertaking that would require a massive collaborative effort with support from the UK Government, broadcasters, and cultural institutions here and in Ukraine. But without an initiative and impulse from Liverpool it will simply not happen. The unprecedented context surrounding the hosting of Eurovision 2023 demands exceptional effort and imagination, and we will never have a more morally compelling case for partners to match rhetoric with tangible resources.

For Liverpool, to quote Liam Fogarty, we should view Eurovision as “the starting block, not the finishing line” in the process of repositioning the city, building our cultural brand and answering the fundamental question posed in Chris Moss’s Telegraph article - what does Liverpool want to be?

Are we content to be the perfect fit, and use the Eurovision stage to repeat what the world already knows - that we’re a place that can deliver a great night out? Or will we use it to express the depth of our generosity and hospitality, the breadth of our imagination and the magnitude of our ambition?

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

The Quest For Utopia

Where once utopian thinkers dreamed of creating the perfect world, today we seem more inclined to expect the worst. Haunted by past horrors and dispirited by dystopian visions of our future, are we right to fear our dreams of perfection lead inexorably to disorder and tyranny? If one person’s utopia is another’s hell on earth, is it time to throw in the towel or should we keep aspiring for better?

Pauline Hadaway

When Eric Hobsbawn, one of the foremost historians of the twentieth century, was invited to address the World Political Forum in 2005, almost fifteen years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, he used his speech to express admiration for Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, and architect of perestroika, who died last week, aged 91. Extolling the almost bloodless transition from communism to post-communism in Eastern Europe, while lamenting the social, economic and cultural catastrophe that followed, Hobsbawn proclaimed that the world had witnessed ‘the last of the utopian projects, so characteristic of the last century’. Perhaps surprisingly, ‘the last of the utopian projects’ was not an allusion to Soviet communism, but rather to the epic triumph of Western capitalism and the associated belief that liberal democracy now represented the final, ideal mode of government. Addressing the Forum - with its audience of political, business and cultural leaders and its impeccably utopian mission ‘to solve the crucial problems that affect humankind today’ - Hobsbawn, a lifelong Marxist, declared that it was the visions of liberal, not socialist utopias that now epitomised the triumph of hope over historical realism.

Two years ago, The Liverpool Salon discussed the economic future of the North, in the light of recently made election promises to level up forgotten towns and regions, where growth had lagged behind the prosperous Southeast. In the middle of Britain’s first national lockdown, the future looked grim, yet barely 12 weeks earlier, UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak had pledged some £640 billion capital investment in roads, railways, schools, hospitals and power networks, promising that ‘no region will be left behind’. After decades promoting the values of individual responsibility, the benefits of privatisation and the evil of state handouts, was a Tory government prepared to rip up its fiscal rule book to lay the ground for a new Jerusalem in Labour’s old northern heartlands? Similarly, Manchester’s metro mayor, Andy Burnham, warned there would be no return to ‘business as usual’, now that the pandemic had exposed the gaps in social care systems and the weaknesses of the gig economy. Appealing for consensus and cooperation, Burnham called on civic leaders to get behind his strategy to ‘build back better’, based on valuing the dignity of labour and fostering mutual dependency and community support. Having grown great cities of culture from the dung of deindustrialisation, were Britain’s metro mayors ditching their enthusiasm for trickle-down economics and dreaming of a return to grass-roots socialism? The world transformed by an unlooked-for natural event is an archetypal theme in utopian – and dystopian – fiction. Were these grandiose visions of transformation to new and better ways of living, a genuine map to the future or nothing more than flights of fancy, designed to distract us all from the deepening political crisis?

Of all the grandiose political projects that emerged from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Marxism, the ideological foundation of Soviet communism, made the most audacious claims – not least of which was the belief in its own historical necessity as part of the onward drive of human progress. However, communism’s grand promises of peace and freedom rang hollow during the period of Soviet communism, which saw the creation of some of the world's most militarized and ruthless police states. The murderous tyranny of Stalin’s Great Purge saw the execution of at least 750,000 people deemed ‘enemies of the state’ with many more sent to the Siberian Gulags. After Stalin, the remaining power and authority of the Soviet system rested on its promise to harness the forces of industrial modernity to banish scarcity and ensure economic security and well-being for all. Though hard to imagine from today’s perspective, the Cold War was as much a competition over the best way to organise the future of humanity, as it was a race to build more nuclear missiles and tanks. The question of which system – capitalism or communism – offered the best means of meeting human needs was central. Looking back, the whole Cold War period abounds in paradox. At its height, and in the midst of a terrifying escalation of the arms race which threatened global nuclear annihilation, and with brutal proxy wars raging in Africa and South East Asia, populations from both sides of the Iron Curtain still maintained their belief in the possibility of peaceful international cooperation. Importantly, both sides still believed in the certainty of future material progress. At a time of rising expectations, as the world tried to put the devastation and depravities of WW2 behind it, the ideological resentments that had frozen East-West relations were simultaneously fuelling intense competition over the rival systems’ capacity to deliver cultural, educational and medical advances and to expand the bounds of knowledge and scientific exploration for – both claimed - the benefit of all mankind.

The struggle between competing visions of the future took a somewhat bizarre turn in 1959 at the opening of the American National Exhibition in Moscow’s Sokolniki Park, designed to display the very best in American life to a curious Russian public – in cars, homes, fashion, art, and - that great icon of American modernity - Pepsi Cola. Against the surreal backdrop of an American model kitchen display, a heated argument erupted between US vice-president Richard Nixon and Soviet First Secretary, Nikita Khrushchev. Nixon boasted that capitalism had provided American steel workers with affordable homes, dish-washers and colour TVs, provoking first-secretary Nikita Khrushchev’s angry riposte:

“Is that what America is capable of, and how long has she existed? 300 years? 150 years of independence and this is her level. We haven't quite reached 42 years, and in another 7 years, we'll be at the level of America, and after that we'll go farther.”

In the shadow of a model kitchen display, US Vice-President, Richard Nixon and USSR Premier, Nikita Khrushchev debated their competing visions of the future before reporters and onlookers at the American National Exhibition (1959). Their impromptu exchange became known as the Kitchen Debate.

The fact that the Soviets were willing to host such an event might be seen as a testament to their own cultural confidence at the time. Thirty years on from the kitchen debate, the USSR had dissolved into chaos, consigned to the dustbin of history, along with its own futuristic visions of space colonization, flying cars, jet-packs and miracle kitchens for all. Good riddance, declared hard-headed economic realists and monetarists like Milton Friedman and Margaret Thatcher, while promptly proclaiming the triumph of their own vision of property ownership and purchasing power as the pinnacle of human happiness and freedom.

This ‘Last Utopia’ was thus conceived as the old one heaved its last, its future guaranteed within a harmonious framework of global institutions and markets, to which there could be no alternative.

‘The impulse to imagine new lands of plenty or to yearn for a vanished golden age is as old as human civilisation. After all, what do the ancient myths of the lost island of Atlantis or of Moses leading his people to the Promised Land constitute but a sense of a better way of doing things always just beyond reach.’

After the shock and pain, first, of the 1970s oil crisis, then of de-industrialisation, the triumph of the free market ushered in an era of abundance, as capital flowed to low-cost destinations, profits soared and cheaper imports drove up standards of living. Falling prices and easy credit brought foreign holidays, electronic goods, luxury cars and miracle kitchens within reach of millions in western democracies and eventually to citizens in the old communist bloc and across the developing world. The 1990s saw the return of large-scale public spending in Britain, investment in schools and hospitals and the beautification of grim post-industrial cities, like Glasgow, Manchester and Newcastle. The expansion of the cultural economy stimulated new industrial activity based on media and communications, tourism, leisure and design. From near-costless telephone calls to online streaming and advanced communication, the giveaway economy of the turn of the century even engendered – albeit briefly - a freewheeling idealism and revolutionary optimism redolent of the 1960s. The global financial crisis of 2008 revealed that the networks of markets and global supply chains holding up this brave new world were little more than a great house of cards.

Thirty years on from the end of the Cold War, we appear to be waving a fond farewell to the promised era of abundance, and witnessing history’s rapid return. As world leaders rub their eyes and adjust to the changed reality, it is still unclear what kind of future will finally emerge from the ruins of the old system. We seem to be approaching a new day of reckoning, when promises of peace and prosperity secured within a harmonious commonwealth of markets may prove as illusory as earlier promises of peace and freedom, begging the question: can a perfect world ever be realised?

Speculation on the ideal state goes back at least to Plato’s account of a perfectly ordered Republic ruled by philosopher-kings, while the impulse to imagine new lands of plenty or to yearn for a vanished golden age is as old as human civilisation. After all, what do the ancient myths of the lost island of Atlantis or of Moses leading his people to the Promised Land constitute but a sense of a better way of doing things always just beyond reach. However, the term utopia, only dates to the beginning of the early modern period, with Thomas More’s 1516 fictional account of the discovery of the island of Utopia, an ideal commonwealth, situated somewhere in the new world, likely southeast of Brazil. Apart from naming a whole genre of political writing and thinking, More’s Utopia brought the speculative premise of building a more perfect order closer to reality. One of the ways of making Utopia seem credible was the adoption of a prevalent form of story-telling: the returning traveller who gives an eyewitness account of a curious distant land that seems both similar, and yet more attractive, pleasing and sensibly ordered than his own.

Taking the voyages of real-life Florentine explorer, Amerigo Vespucci as its model, More’s Utopia purported to be a literal rather than allegorical account. The supposed truth of Utopia’s perfections comes with a caveat from the author that fantasies of human perfection inevitably fall apart in the encounter with reality. While More, ever the sceptical narrator, frequently pokes fun at the absurdities of the Utopian system, the credibility of the tale he recounts is undermined by the name he gives to his traveller: Hythloday, Greek for ‘talker of nonsense’. Indeed, the first utopia effectively demolishes the whole utopian premise. More coined the word from the Greek ou-topos meaning 'no place' or 'nowhere', with a nod to the almost identical Greek word eu-topos which means a ‘good place’. In other words, the ideal place that does not exist.

‘The idealisation of a centrally organized international order, dominated by great powers, governed by a professional administration, consulting with teams of academics, lawyers, diplomats, philosophers, doctors and entrepreneurs, while keeping the masses at arms-length from political decision-making, only goes to show that one man or woman’s dream of utopia is another’s idea of hell on earth.’

One of the most striking of Utopia’s many excellent perfections arises from the absence of private property and the abolition of money, where all things are held in ‘common to every man’. A century later, a very different vision of perfection was created in the highly technocratic Bensalemite nation depicted within Francis Bacon’s novel, New Atlantis. For the rulers of Bensalem, perfection lay in an endless expansion of knowledge and power over nature to enlarge ‘the bounds of Human Empire, to the effecting of all things possible.’ The imaginary government, economy, laws, practices of war, customs and religions of More’s humanist and Bacon’s scientific utopias recognisably prefigure numerous social and economic experiments that have followed in Britain, Europe and the United States. Published 150 years after Utopia, James Harrington’s, The Commonwealth of Oceana was both an exposition of an ideal constitution and a practical guide for the government of England’s new Cromwellian republic. Those who chose to abandon England for a better life in the American colonies often did so in pursuit of their own dreams of utopia, like the seventeenth-century Puritans with their ‘city on a hill’ in Massachusetts Bay.

Having taken concrete form in the English, American and French revolutions, utopian ideals of liberty, equality, the pursuit of happiness and a more harmonious order have become deeply embedded in the political psyches of men and women in the modern world. The nineteenth-century was a particularly fertile time for social experimentation, with the utopian socialism of Charles Fourier and Robert Owen inspiring attempts to establish ideal communities in Europe and the US. Enlightened industrialists built their own ideal company towns, like Saltaire in Bradford, Merseyside's Port Sunlight and Pullman in Chicago, designed to showcase the potential beauty and order of life under industrialism capitalism.

Utopia in space. In 1975, after a study into future space colonies, Nasa commissioned a series of illustrations to imagine what they might look like. Technology and nature sat side-by-side in this doughnut-shaped structure. Rick Guidice / NASA Ames Research Center

Characteristically sceptical of utopianism, the liberals and neoliberals were latecomers to the quest for utopia. W.E. Gladstone, the first great leader of the Liberal party, proclaimed that he would not be diverted from the task of ‘effecting great good for the people of England’ by speculating on ‘what might possibly be attained in Utopia’. By the end of the nineteenth century those sections of Liberal thought critical of the ‘false phantoms’ of imperial glory - the little Englanders and the Manchester Liberals, like Cobden and Bright - had given way to the proponents of global expansion, which saw Britain as a force for good in the world. After the horrors of the Great War, Liberal utopians contemplated a future world state, set up and led by an enlightened committee of wise and tolerant rulers, rather like the ‘voluntary nobility’ imagined by H.G. Wells in the novel, A Modern Utopia. The idealisation of a centrally organized international order, dominated by great powers, governed by a professional administration, consulting with teams of academics, lawyers, diplomats, philosophers, doctors and entrepreneurs, while keeping the masses at arms-length from political decision-making, only goes to show that one man or woman’s dream of utopia is another’s idea of hell on earth. Oscar Wilde wrote that ‘a map of the world that does not include Utopia is not even worth glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which humanity is always landing’. When humanity lands, he went on to say, ‘it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail’. While many of the problems and imagined solutions that excited early utopian thinkers continue to perplex us, our enthusiasm for setting sail in search of new worlds has – not surprisingly – faded.

Oscar Wilde rightly observed that the realisation of utopia lies in material progress. Today, however, we seem more inclined to expect the worse, than hope for better times. In another paradox, the triumph of capitalist democracy appears to have deepened the level of hostility towards the historical benefits it has achieved. Mass consumption is reviled as crass consumerism, manufacturing and scientific progress seen as destroyers of the planet, while popular democracy is recast as dangerous populism. Believing that history has taught us that the road to dystopias of disorder and tyranny are paved with dreams of perfection, Faustian dystopias haunt our dreams of building a better world. For new generations setting out on their own quest for utopia - at the end of the end of history - the fundamental question is not so much the possibility, but the desirability of realising a perfect world.

Pauline Hadaway is a writer, researcher and co-founder of The Liverpool Salon, which has been hosting public discussions around philosophical, political and cultural topics on Merseyside for over seven years.

Book Now

The Liverpool Salon presents The Quest for Utopia

Liverpool Athenaeum, Thursday 15 September 6.30 pm

Buy tickets

Join us at Liverpool’s iconic Athenaeum club for The Quest for Utopia, the first in a new series of public conversations that take utopia and dystopia as themes for exploring the possibilities of building other, and better, societies, while reflecting on the shortcomings of our own.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

It’s Time to Get Interesting

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to Manchester’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

Jon Egan

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to the city’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

This long-forgotten televisual gem was brought to mind by a recent tweet from Liverpolitan which observed, sagely, that when Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of his own city’s expanding psychogeography. Under Burnham’s monarchic reign, Manchester has become the fulcrum of an aspiring northern nation. Its status as capital of the north is beyond dispute. Michael McDonough’s visionary prospectus for Liverpool’s Assembly District as a home for pan-northern regional government (beautiful and inspiring though it is) is destined to remain another sadly lamented ‘what if’. Liverpool’s own claims to northern dominance are a boat that has long since sailed and, like a great deal of our city’s historic wealth and prestige, are now securely moored at the other end of the Manchester Ship Canal.

Sorry if this sounds fatalistic and defeatist, but it’s an unavoidable truth. Manchester as regional capital has already happened and I can’t help feeling it’s actually entirely apposite. Liverpool is not, never has been and never will be the capital of the north for a very simple reason - we’re not in ‘the North.’

Let me explain. Some years ago when pitching for the brief that became the It’s Liverpool city branding campaign, my agency team and I presented an extract from a speech by then Tory Minister for Transport, Phillip Hammond. In it, he had been extolling the benefits of HS2, which he prophesied would unleash the potential of “our great northern cities.” To emphasise the point, and presumably to educate his London-centric media audience, he decided to identify these hazy and distant provincial relics that would soon benefit from an umbilical connection to London’s life-giving energy and dynamism. Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Sheffield, Bradford and even Newcastle (which wasn’t in any way connected to the proposed HS2 network) all made it on to his list. Our pitch focussed on Liverpool’s conspicuous absence from Hammond’s litany. We weren’t (as I opined in an earlier offering to this publication) ‘on the map’. We deduced that the speech was one more piece of definitive evidence that Liverpool wasn’t considered sufficiently great to merit a mention - nor important enough to be connected to a flagship piece of national infrastructure. But on reflection, there may have been another reason for the city’s omission. Perhaps we weren’t sufficiently northern! As if the inclusion of the offending syllables liv-er-pool would have somehow derailed this Lowryesque invocation of smoke stacks, cloth caps and matchstalk cats and dogs.

Of course, we are not talking about The North as a geographic region, or even an amalgam of richly diverse sub-regions, but as a mythic construct. However, as the French philosopher and founder of semiotics, Roland Barthes, would argue, myths are always distortions, albeit with powerful propensities to overcome and subvert reality. In this sense, northernness is not merely a point on the compass - It’s a complex abstraction, a constituent part of the English psyche and self-image that has strong connecting predicates and excluding characteristics. Geography alone is not enough to discern where The North begins and which enclaves and exclaves are to be considered intrinsic to its essential terroir. Isn’t Cheshire really a displaced Home County tragically detached from its kith and kin by some ancient geological trauma?

Thus when Government Ministers or London-based media commentators pronounce on "The North" they are all too often referencing a cloudy and amorphous abstraction defined not by lines on maps, but by indistinguishable accents, bleak moorlands and monochrome gloomy townscapes, nostalgically referred to as ‘great cities’. From this perspective, northerners are seen as honest, hardworking souls, who used to make things (when things were an important source of wealth and national prestige). Though stoical and resilient, they have a tendency, every generation or so, to get a bit bolshy, at which point it becomes necessary to reassure them of their place in our national life by relocating part of a prestigious institution to a randomly selected northern location, or by staging a second-tier sporting event such as the Commonwealth Games or perhaps even placating them with some vague commitment to ‘re-balancing’.

“When Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of Manchester’s expanding psychogeography.”

Manchester has been brilliantly adept at securing for itself more than its just share of these charitably dispensed national goodies. Largely that’s through a typically northern resourcefulness and pragmatism, but also because the city has ingeniously positioned itself as a shorthand synonym for the very idea of northernness.

Peter Saville CBE, the graphic designer who art-directed Factory Records and designed their most iconic album sleeves, also created the acclaimed Original Modern branding for Manchester in 2006. A predictably beautiful piece of graphic creation, it wove a vivid palette of cotton loom colours to represent a new Manchester, that was proud of its pioneering past but wanted to take that innovative DNA to recreate itself in the 21st century. It was wildly popular, but as an exercise in “re-branding” it didn’t succeed in challenging or reframing Manchester’s perceived identity. Instead, it merely set out to transmute it into something more contemporary and serviceable. Saville's project was to dig deeper into the Manchester’s vernacular version of mythic northernness, reflecting no doubt his immersion in Factory's overtly industrial aesthetic. It’s a restatement of core northern traits and a celebration of the city’s long-established narrative - the hub of the industrial north. Manchester’s sense of modernity was less about today and more an evocation of the 19th century, when it was considered the workshop of the world. Its originality was brilliantly expressed by the historian, Asa Briggs, who described it as the “Shock City of the age” - an urban phenomenon without peer or precedent in Europe and only matched by Chicago in North America. Cut forward to the early years of the Noughties. The opening of the ill-fated Urbis project – a new ‘Museum of the City’, conceived by Justin O’Connor and designed by Ian Simpson, was a bold assertion in shining glass and steel of Manchester’s boast to have been the world's first industrial city and the birthplace of the modern age. Despite the powerful statement of brand identity, it was a hopelessly unsuccessful attraction, closing after only two years in 2004. Its director candidly admitted that this monument to the city’s inventive and industrious spirit simply “didn’t work.”

Peter Saville’s Original Modern. Despite the fresh lick of paint, Manchester’s new branding campaign was curiously backward-looking.

In my article, Vanished. The city that disappeared from the map, I suggested that one radical option for Liverpool was to stop trying to compete with its eastern twin. Instead, I argued, we could become a new kind of urban entity - a city with two poles, which pooled our joint assets and balanced the two hemispheres of human consciousness to forge a global metropolis that could re-balance Britain without needing to turn to the patronising benevolence of London. Two hundred years after the building of the world’s first inter-city railway between Liverpool and Manchester, it seemed like a plausible and timely possibility to explore. I was wrong. Not because this idea is manifestly an anathema and heresy to every patriotic Liverpolitan (except me, it seems), but because Manchester is definitively and inexorably set on its own northern trajectory (even to the point where its most creative and happening urban district is aptly branded the Northern Quarter). Unlike Liverpool, Manchester's identity is embedded in its geography, and its literal place in the world. Its compass has only one co-ordinate and it isn’t west.

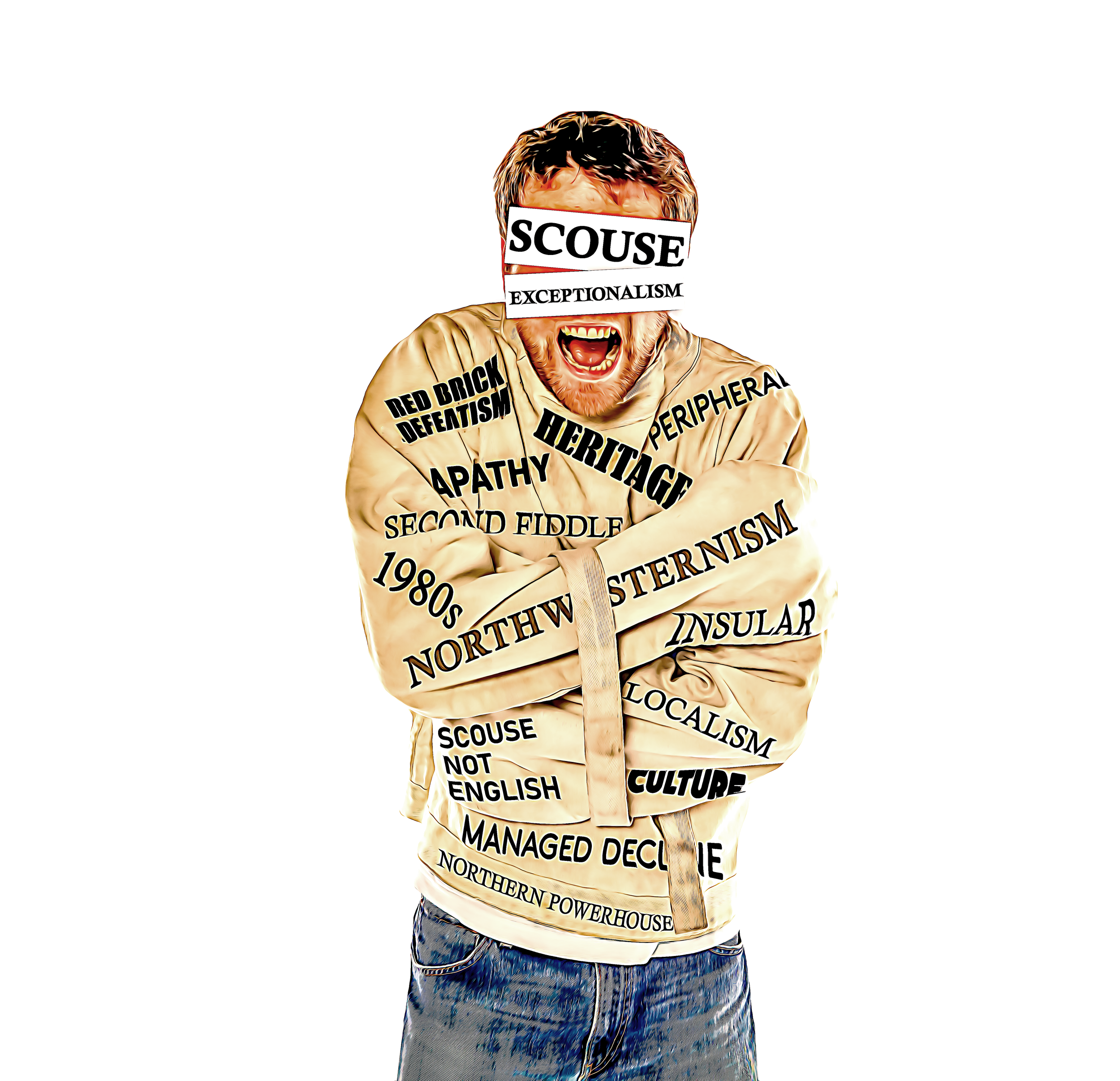

So where does that leave Liverpool? If we’re not part of The North, where in the world are we? Exiled and dislocated from our northern hinterland, we are a place apart; liminal and strangely detached from mundane geography. The recent media frenzy occasioned by the booing of the national anthem by Liverpool FC fans reignited a predictably shallow rehash of the “Scouse not English" debate, with the now familiar allusions to Margaret Thatcher’s alleged but never conclusively proven project to euthanize the city, compounded by the tragic injustice of Hillsborough. But these events were not the beginning of Liverpool's estrangement from its northern and English identity and its gradual drift to the edge of otherness. When in the second half of the 19th century our “accent exceedingly rare” began to emerge as something radically different to the dialects of neighbouring Lancashire, it was disparaged as “Liverpool Irish” - a vernacular that was deemed to be both alien and inherently seditious. As late as 1958, in Basil Dearden’s film Violent Playground - a British-take on the then topical theme of “juvenile delinquency” - the Liverpool street gang, led by a youthful David McCallum, are portrayed with accents that one reviewer of the DVD release, observed, “curiously owe more to the Liffey (Dublin's river) than the Mersey.” We were quite literally being depicted as foreigners in our own country.