Recent features

Eurovision 2023: Liverpool’s Imperfect Pitch

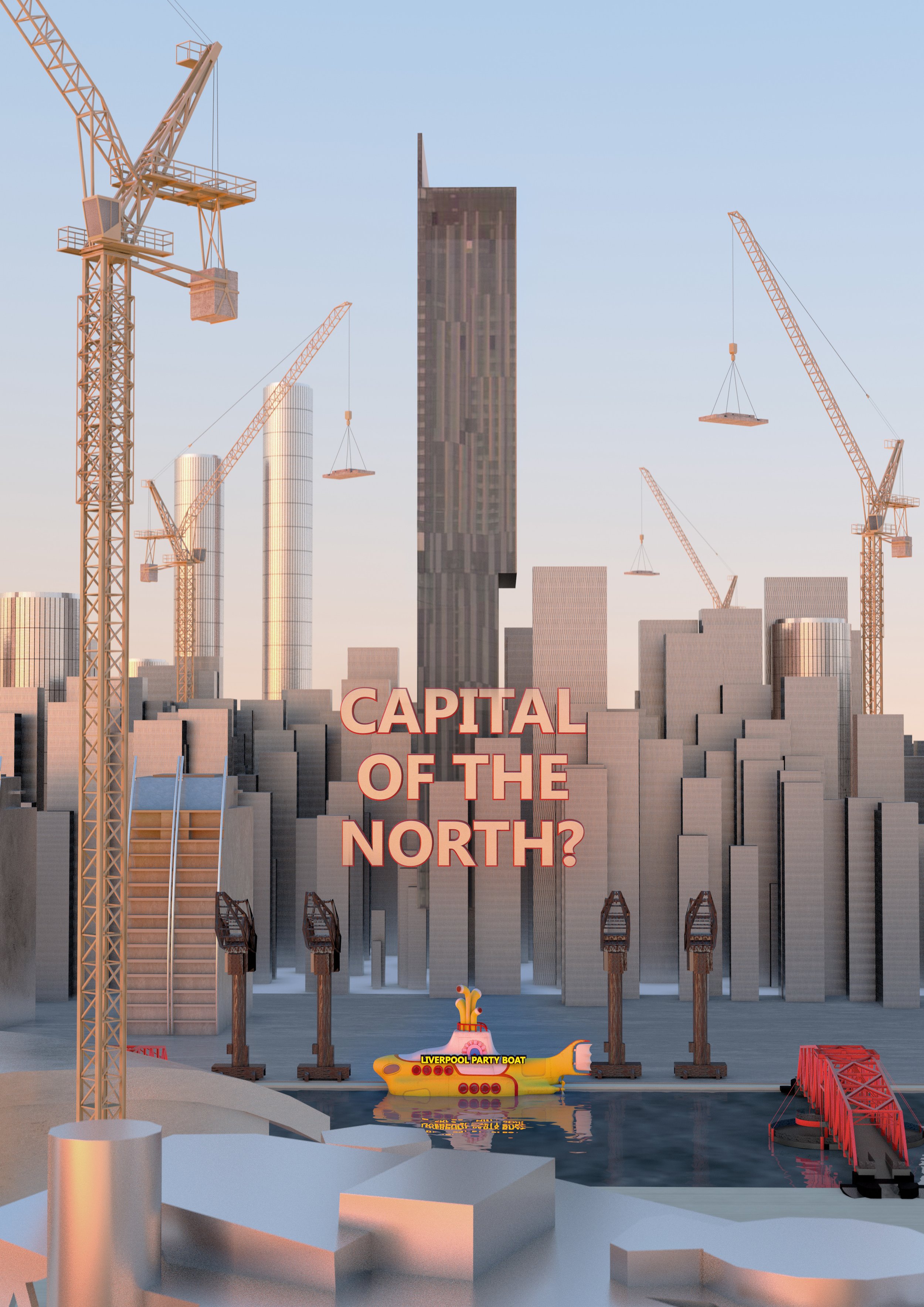

When Liverpool won the right to host Eurovision 2023 on behalf of war-torn Ukraine, most people in the city celebrated. With its reputation for music and for fun nights out, allied to its compassionate heart, the city was seen as the perfect fit in difficult times. But some have warned that in mistaking kitsch for cool Liverpool risks reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of its cultural brand. Jon Egan wonders how we can subvert expectations to deliver on the European Song Contest’s higher purpose.

Jon Egan

Amidst the near-universal jubilation at Liverpool’s successful bid to stage Eurovision, I struggled to suppress an almost inchoate feeling of dissident cynicism. Is the European Capital of Culture now pitching its future identity on an ambition to be the European Capital of Light Entertainment?

Liverpool is a perfect fit for Eurovision we are told by the bid’s architects and cheerleaders, though this natural synergy with an event that was until very recently derided as a festival of musical mediocrity is at the very least an arguable proposition. No disrespect to Sonia (creditable second) and Jemini (nul points), but they are rarely name-checked when the city intones the sacred litany of its popular music icons. As travel writer and destination expert, Chris Moss opined in his recent Daily Telegraph article; “From Echo and the Bunnymen to The Farm, from The Mighty Wah to The Lightning Seeds, pop and rock culture in Liverpool has always been anti-establishment, iconoclastic and often disdainful of national media-driven circuses."

I’m old enough to associate the Eurovision Song Contest (as it was called once upon a time) with Katie Boyle, a BBC stalwart and actress whose deft professionalism and elegant gentility made her a perfect fit as TV host for an earlier incarnation of the continent’s festival of song.

I’m not quite old enough, however, to remember, what is now my favourite ever Eurovision-winning performance, France Gall’s weirdly off-key rendition of Serge Gainsbourg’s ironic masterpiece, Poupee de Cire, Poupee de Son. Yes, there was irony at Eurovision long before Conchita Wurst or the knock-about stage-Irish buffoonery of the late Sir Terry Wogan.

Eurovision’s durability is doubtless its capacity to adapt to the changing mores of social convention and popular culture, not to mention the seismic disruptions to the boundaries and very identities of its competing nations. Which of course, takes us to 2023 and a Eurovision overshadowed by the tragedy of war in Ukraine. So it’s time for me to swallow my cynicism and recognise that this Eurovision is more than a celebration of blissful superficiality. Eurovision, which was conceived as an event to help bring a war-ravaged continent back together, has rediscovered a higher purpose and it’s up to us to deliver it.

There are already some encouraging signs. Claire McColgan and her team are planning an events programme that will celebrate Ukrainian culture in its many guises and remind the watching millions why this is happening here and not there. Liverpool’s Cabinet Member for Culture, Councillor Harry Doyle, told a gathering of stakeholders that he’s open to ideas about how the city can derive the maximum benefit and the most enduring legacy from next year’s Eurovision. So, if Harry wants my two penn’orth worth, here goes.

Whilst researching an article for the Daily Post sometime in the run-up to the European Capital of Culture, I asked David Chapple, a former Saatchi & Saatchi creative and regular visitor to the city, how he would market Liverpool. His answer was stark and challenging -“Stop telling people what they already know, surprise them!” I’m not sure that we have ever managed to live up to David’s exhortation. As Chris Moss warns, there is a danger that by claiming a perfect fit with an event that “mistakes kitsch for cool” we may simply be reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of Liverpool’s cultural brand. Moss, born and bred in neighbouring St Helens, believes that a city that should be the UK's foremost cultural destination is committing another branding "blunder" (having tossed away its World Heritage Status) by claiming an almost umbilical affinity with what he provocatively dismisses as a "naff, brainless extravaganza."

Moss's rhetoric may be extravagant, but there is more than a kernel of truth in the proposition that we have consistently failed to articulate and market the breadth and quality of our cultural offer. Ensuring Eurovision simply doesn't serve to reinforce a constraining stereotype, has to be a guiding imperative.

“There is a danger that by claiming a perfect fit with an event that “mistakes kitsch for cool” we may simply be reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of Liverpool’s cultural brand.”

So rather than being the perfect fit, let’s set out to design an imperfect fit. Let’s confound expectations, stretch the envelope and deliver a gathering that offers more than the “glitter and sparkle” that Doyle describes as the essence of Eurovision, but also explores what he terms (somewhat vaguely) “the added layer of Europe.”

I’m certain that Harry, Claire and their team are sincerely committed to ensuring Liverpool’s Eurovision acknowledges the wider European and specific Ukrainian context, although the confectionary metaphor suggests an application of icing rather than an especially bespoke cake mix. Surely now more than ever the “added layer” is the essence.

Returning to David Chapple and his urgings to surprise, the challenge to Liverpool would be how do we stage and wrap Eurovision in a way that confounds stereotypical perceptions of the city, that expands and subverts expectations while revealing a facet of unsuspected seriousness and cultural depth? Given the unique circumstances of this gathering, it seems like an appropriate juxtaposition to pitch the exuberant excess of Eurovision with a broader conversation and cultural exploration of the event's unsettling backdrop.

Notwithstanding Joanne Anderson’s excusable hyperbole that “the eyes of the world will be on Liverpool,” Eurovision 2023 will attract enormous numbers of visitors and serious levels of media attention. Liverpool needs to embrace the opportunity, and the responsibility, to do more than simply host Europe’s ultimate carnival of camp.

Are there media partners with whom we could convene a Eurovision of Ideas - a virtual or even physical gathering of thinkers, policy-makers and artists from Ukraine, the UK and Europe to explore how the shattering reality of yet another European war can help us to forge a deeper and more durable sense of solidarity and a shared future?

Is there space to stage an expo for Ukrainian businesses including their burgeoning technology sector, to help them forge new contacts and explore new markets?

For Ukraine, Eurovision has become a symbolic staging post in a journey from isolation and the cultural suffocation of the Soviet era. This war is a painful and bloody episode within the struggle for a new cultural and economic relationship with its estranged continent. So, how do we ensure that the celebration of Ukrainian culture proposed by Claire McColgan is sufficiently resourced to be immersive and integral and not merely a quaint window dressing for the main event? Culture Liverpool is bidding for funds to deliver a European-themed cultural programme, but an email to cultural organisations inviting bids was hastily withdrawn in the absence of any definite funding commitment from Arts Council England. These are early days, but this is not a positive omen.

In a recent conversation with me, journalist and commentator, Liam Fogarty speculated that if Manchester or Glasgow were staging this Eurovision, the scale of ambition might be greater and the prospecting for partners, funders and co-creators more lateral and imaginative. He is perhaps not alone in that thought. For the first time in nearly two decades, we have been successful in a major bidding competition, but what happens when the circus leaves town? What's our pitch to ensure a positive legacy and how do we create this event in a way that shows a previously unsuspected vista of a more interesting and multi-faceted city?

This is a huge opportunity to redress the imbalance of cultural investment towards London (and even Manchester) by demanding the resources to give a platform to the diversity of a resurgent Ukrainian culture, emerging from what contemporary poet, Lyuba Yakimchuk has described as a “war of decolonisation.” At the end of the day, we’re standing in for the place that would, but for the obscene brutality of Putin’s invasion, be hosting this event. So, let’s stretch every sinew and apply every creative impulse to celebrate the identity of a nation that a deranged tyrant is seeking to wipe off the face of the map.

And of course, we already have a connection and relationship with a Ukrainian city dating back to the early 1950s when Odesa was in the Soviet Union. In truth, Liverpool’s twinning relationship with the Black Sea port had become a largely hollow civic anachronism - a relationship long since packed away in the lumber room of municipal memorabilia. Until now, the cultural highlight of the twinning relationship was an impromptu concert by Gerry Marsden on the Potemkin Steps when the Merseybeat legend led an aid convoy after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

“For the first time in nearly two decades, we have been successful in a major bidding competition, but what happens when the circus leaves town?”

For Odesa, threatened with invasion and subject to merciless missile strikes, friendship and solidarity have acquired a new and vivid resonance. Steve Rotheram's ambition to make Eurovision Odesa’s “event as much as our own” is generous and laudable but it will only be honoured by a substantial financial and imaginative investment and genuinely collaborative curation.

Without prescribing what a co-created cultural programme might look like, there is massive scope for stunning and surprising collaborations. One of the many intriguing (and sadly unrealised) ideas championed by the much-maligned Robyn Archer, whose brief tenure as Creative Director for Capital of Culture 2008 marginally exceeded Liz Truss’s occupancy of 10 Downing Street, was to stage performances by the Dutch National Opera in the semi-dilapidated grandeur of Liverpool Olympia. Notwithstanding Liverpool’s uncharacteristic failure to extend our famed hospitality to the soon-to-be homeless English National Opera, we could perhaps invite Odesa’s renowned opera company to be part of our Eurovision cultural celebration in their sister city. Whether at the Empire, Olympia (or even my long cherished dream to stage opera in the epic setting of St Andrews Gardens aka the Bullring), we could at the very least promise them a performance that would not be interrupted by air raid sirens or the rumble of distant explosions.

Sharing the Eurovision limelight with Odesa must be the beginning of a longer-term commitment to work with a city still under daily Russian bombardment. Beyond cultural and humanitarian co-operation, there may be a myriad of ways in which we can assist with trade and reconstruction. Even before the damage inflicted by Russian missile and bombing strikes, Odesa's Soviet-era port infrastructure was in dire need of investment and modernisation. Through a concordat for economic co-operation between the two cities, Liverpool should be using the exposure of Eurovision to gather together and broker the expertise and potential investment partners to help Odesa recover from the trauma and devastation of the present conflict.

All this may seem too ambitious, unrealistic or even unnecessary. At the end of the day, all that’s expected of us is that we put on a show, manage the organisation with reasonable efficiency and make an appropriate gesture to recognise the special circumstances of this Eurovision.

Maximising the opportunity and legacy is an undertaking that would require a massive collaborative effort with support from the UK Government, broadcasters, and cultural institutions here and in Ukraine. But without an initiative and impulse from Liverpool it will simply not happen. The unprecedented context surrounding the hosting of Eurovision 2023 demands exceptional effort and imagination, and we will never have a more morally compelling case for partners to match rhetoric with tangible resources.

For Liverpool, to quote Liam Fogarty, we should view Eurovision as “the starting block, not the finishing line” in the process of repositioning the city, building our cultural brand and answering the fundamental question posed in Chris Moss’s Telegraph article - what does Liverpool want to be?

Are we content to be the perfect fit, and use the Eurovision stage to repeat what the world already knows - that we’re a place that can deliver a great night out? Or will we use it to express the depth of our generosity and hospitality, the breadth of our imagination and the magnitude of our ambition?

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

The Beatles: Inspiration or dead weight?

When does city pride in the Fab Four turn into a hindrance to future achievement? Jon Egan argues that the city of Liverpool is in danger of becoming a Beatles theme park, and its world conquering band a crutch to exorcise the painful intimations of our diminished relevance and prestige. In looking to the past, have we forgotten what made John, Paul, George and Ringo so special - their fearless embrace of the avant-garde, the contemporary and the new?

Jon Egan

There was something profoundly true and desperately sad in University of Liverpool lecturer, Dr David Jeffery's acerbic observation that "Liverpool is a Beatles' shrine with a city attached."

It is the dispiriting obverse to music journalist, Paul Morley's rhapsodic description of Liverpool as "a provincial city plus hinterland with associated metaphysical space as defined by dramatic moments in history, emotional occasions and general restlessness."

Jeffery's comments on Twitter appear to have been inspired or provoked by the recent announcement that Liverpool would be using a £2 million grant from Government to advance the business case for yet another "world-class" and "cutting-edge" Beatles' attraction on our hallowed waterfront. Presumably, it will be sandwiched somewhere between the Beatles statue and The Beatles Experience and conveniently close to The Museum of Liverpool and The British Music Experience with their not inconsiderable collections of Beatles artifacts and memorabilia. The exact nature of this new cultural icon remains a little unclear, however, amidst wildly differing descriptions offered by our City and Metro Mayors.

What is deeply depressing about this announcement is that it suggests that Liverpool is incapable of imagining any kind of cultural proposition that is not predicated on the seemingly inexhaustible allure of the four boys who shook the world.

There is of course a readily available and seemingly plausible justification for the never-ending Beatles' fetish, and that is the claim that they are the anchor for our hugely important tourism economy. Notwithstanding the implication that David Jeffery is right to suspect that the city is consciously morphing into a Fab Four theme park, I suspect that this is not exactly the whole truth. For Liverpool, The Beatles are a crutch, a cherished emblem of identity and importance used to exorcise painful intimations of diminished relevance and prestige.

In the novel, Immortality, Czech writer Milan Kundera tells the story of the man who fell over in the street, who on his way home stumbles on an uneven pavement, falls to the ground and arises dazed, grazed and dishevelled, but after a few moments composes himself, and gets on with his life. But unbeknown to the man, a world famous photographer happens to witness the scene and quickly snaps an image of the bewildered and bloodied pedestrian. He subsequently decides to make this picture the cover image for his new book and the poster for his international exhibition. For the man, a momentary misfortune freeze-framed, replicated and disseminated across the world, becomes the image that will forever define who he is.

The more we conflate the Beatles brand with the city's identity, the less space we have to imagine anything original, contemporary or remarkable.

In a sense, Liverpool is the City that fell over on the street, our external image is in significant part, defined by a succession of misfortunes, afflictions and tragedies that befell the city over two decades at the end of the last century. These events forged images, preconceptions and stereotypes that still blight us today and have never been successfully exorcised or replaced.

The Beatles hark back to a time before this blight, when Liverpool was in Alan Ginsberg's celebrated phrase, "the centre of consciousness of the human universe." They are, I believe, a therapeutic distraction from the task of making a different story or discovering a new identity.

Culturally, our Beatles fixation is unhealthy, debilitating and regressive. In fact, I fear we are reaching a point where The Beatles will become the single biggest impediment to any form of civic progression, or any serious project to make Liverpool important, interesting or relevant in today's world. If we are going to have a civic conversation about what kind of "world class" Beatles attraction should be erected at The Pier Head, my immediate impulse would be to recommend a mausoleum.

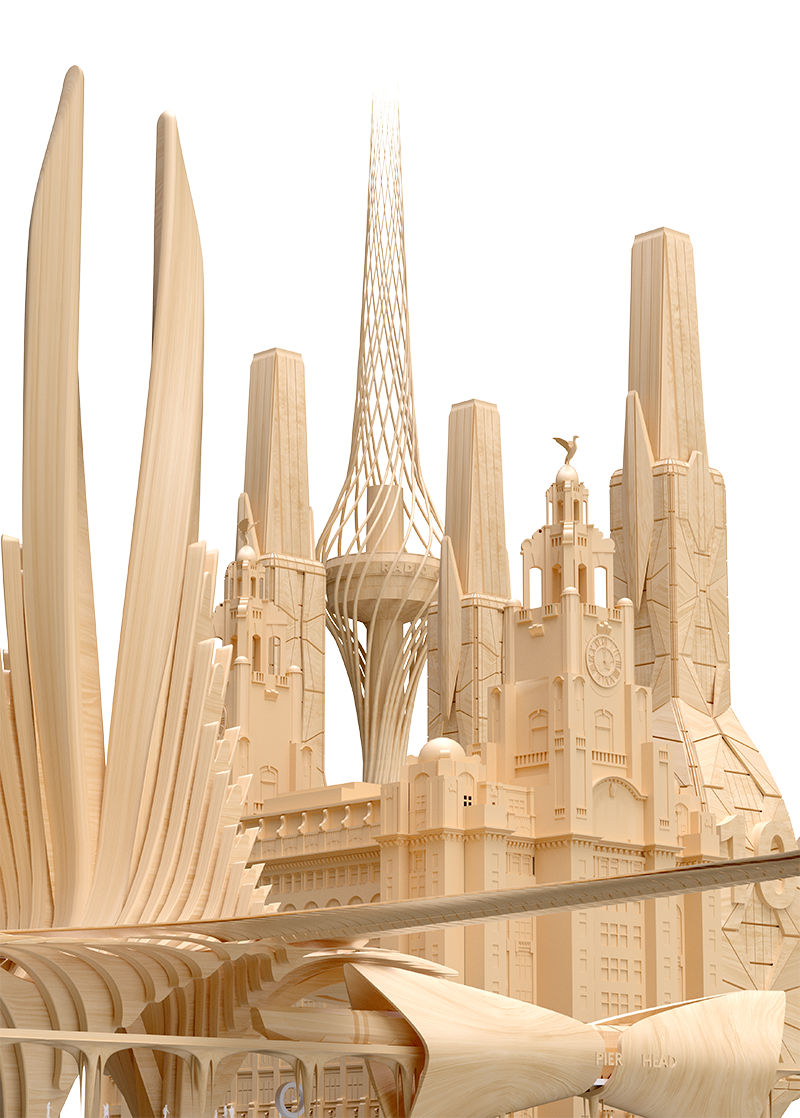

But perhaps a more imaginative and original idea was the one offered by the late Tony Wilson. That supreme Mancophile, Factory Records producer, Granada TV reporter and founder of the Hacienda nightclub was never held in particularly high regard in this city, especially following some tongue in cheek words of encouragement he gave to Club Brugge on the eve of their European Cup semi-final with Liverpool in 1977. Scousers may resemble elephants with respect to their prodigious powers of memory, but our skins can sometimes be just a tiny bit thinner. Tragically, Wilson's Mancunian persona and his tendency to lapse into casual profanity whilst presenting his project to civic decision-makers proved the undoing of his brilliant and visionary proposition for POP - the International Museum of Popular Culture. Pitched as the big idea for the European Capital of Culture, and the solution that would provide content for Will Alsop's audacious but otherwise functionless Fourth Grace, POP was a talisman for instant reinvention - a Beatles-inspired attraction without any reference to The Beatles. Alas it never happened.

Wilson had first dreamt of POP as an adornment for his own native city and a fitting celebration of its notable contribution to the history of modern popular music, but he soon realised that it was the right idea for the wrong place. He would often express irritation that when travelling in the US he would frequently have to explain where Manchester was by reference to its proximity to Liverpool - a place that people had actually heard of. And there was also the grudging recognition that at a time when Liverpool was "the centre of the human universe" globalising popular culture - Manchester could only offer us Freddy and The Dreamers. Even the outrageous charisma of Manchester United football god, George Best was derivative as he was often dubbed the 5th Beatle.

POP would not simply have been about popular music, it would encompass every facet of popular culture, every expression of contemporary creativity in film, TV, advertising, games, cars, sport, fashion, digital technology and consumer culture. And it was proposed for Liverpool because this was the place that spawned a phenomenon that reached the four corners of the Earth. It was a moment when the world discovered a common currency and a cultural vernacular intelligible to every ear.

POPs content would be dynamic and ever-changing, a continuous exposition of the new, curated by global creatives, designers and technologists. It would be Liverpool recovering its world city perspective and its capacity to invent and innovate - the pool of life, the birth canal for the extraordinary and the unprecedented. Its ingenious paradox was its implicit assertion that The Beatles did not make Liverpool, but Liverpool made The Beatles.

They monopolise our self-image occluding facets of identity and history now only half-glimpsed in the penumbra of a shadowy scouse dreamtime.

All of which is a million miles from Steve Rotheram's "world-class immersive experience" which he promises us will be more spectacular than a glass cabinet containing John Lennon's underpants. We can hardly wait.

If all we can possibly imagine are The Beatles etherealised into holograms - almost literally spectres from beyond the grave - then David Jeffery is right and Liverpool's once rich and cosmopolitan culture has collapsed into a black hole of redundant clichés. The more we inflate our Beatles offer and conflate their brand with the city's very identity, the less space we have in which to imagine anything original, contemporary or remarkable. Along with football (which at least tells new stories) they have come to monopolise both our external brand and our officially curated self-image, occluding facets of our identity and history that are now forgotten and suppressed, only half-glimpsed in the penumbra of a shadowy scouse dreamtime.

The Beatles have come not only to represent our brand, but have also helped to define our personality, attitude and accent - cheeky, chippy, sassy and defiant. As emblems of the 60s social revolution, they helped to forge and reify the idea of Liverpool as a working class city - or more accurately an exclusively working class city. As rock journalist Paul duNoyer, notes in his book, Wondrous Place, this is both a false and profoundly disabling imposition. Not only, as Tony Wilson asserted, are we the city that globalised popular culture, but we are a city that has contributed massively to every facet of culture, ideas and invention over the last 200 years.

The world's first enclosed dock and inter-city railway, together with the completion of the Transatlantic telegraph cable, are not only stunning achievements in technological innovation, but bolster the credible claim that globalisation began here.

The extent to which we have been willing to squander or disown the breadth of our cultural heritage was brought home to me in the febrile final stages of the European Capital of Culture bidding competition. Having commissioned pop artist, Sir Peter Blake to create a homage to his iconic Sgt Pepper album cover to remind the world, or at least the judging panel, of Liverpool's cultural and intellectual prowess, the task of deciding who exactly was worthy of inclusion was both fraught and enormously revealing. Apart from a few contemporary, and at the time highly topical creatives including the poet Paul Farley, artist Fiona Banner and film-maker Alex Cox, the principal criterion for inclusion appeared to be the directness or intimacy of connection to The Beatles. A lop-sided bias towards musicians, popular entertainers and Sixties icons meant no room for the likes of painters George Stubbs and Augustus John, poets Nathaniel Hawthorne and Wilfred Owen, novelist Nicholas Monsarrat, playwright, Peter Shaffer or even poet and novelist, Malcolm Lowry the author of the celebrated, Under the Volcano. Incredibly, until Bluecoat Artistic Director, Bryan Biggs' finally succeeded in persuading Wirral Council to erect a blue plaque on New Brighton's sea wall, there was virtually no public recognition that one of the 20th century's greatest and most influential novelists had any association with the Liverpool City Region.

Without questioning or diminishing the impact of the Mersey Sound poets (McGough, Henri and Patten) in the 1960s, their literary status is no way comparable to another unsung and forgotten cultural luminary with a significant Liverpool connection - C.P. Cavafy. Now acknowledged as one of the last century's most important and original poetic voices, Cavafy spent much of his childhood at addresses in Toxteth and Fairfield. Greek and gay, his poetry will forever be associated with the city of Alexandria where his family settled after leaving Liverpool. We do not know to what extent his formative years in the city helped nurture Cavafy's creative animus, but transience, up-rootedness and departure are woven into our narrative. Our sense of self and place in the world as Liverpolitans, owe as much to those who moved on, or merely passed through, as they do to those who stayed or settled here.

We are not, and never have been a monochrome canvass or a one trick city. Our culture is dense, deep and multifarious, formed by a hotchpotch of races, creeds and classes. For those tasked with defining a place and communicating its uniqueness to the world, there is always the temptation to reduce and simplify.

Brands, including place brands, are often conceived like Platonic forms - a distilled essence, fixed and immutable. But cities like Liverpool are neither simple nor static, and are thus frustratingly un-brandable. Described by Wilson as a place with "an innate preference for the abstract and the chaotic," our essence is pre-Socratic - unresolved, unpredictable and disconcerting. We know that port cities like Liverpool, Naples, Barcelona and Marseilles have historically been melting pots for ideas, influences and cultures - places where things never quite settled.

But their edginess is not merely a function of a perturbed diversity, it is also literal. It's connected to Marshall McLuhan's philosophical idea of right hemisphere sensitivity and the expanded perspective of what he terms acoustic space. Ports face outwards, they are perched on the precipice of a vast and formless abyss. It's an omnipresent reminder that there are no limits.

For Paul Morley, Liverpool’s character and identity - its ability to charm, entertain, inspire and infuriate - proceed from an inchoate restlessness and fidgety creativity. It's a place "where something happens, most of the time, leading to something else." But it seems like that creative energy and inventiveness have deserted us - or at least our leaders. What was once an animating pulse has been reduced to a piece of hollow rhetoric - a brand attribute.

It's sad that a UNESCO City of Music should have forsaken polyphony, and that we are continually stuck in a repetitive groove, narrowing our identity and stifling our capacity to be original (again). For this reason the very last thing Liverpool needs is yet another Beatles' attraction, even an immersive one.

So, OK, The Beatles were important, are important. They changed the world, but did they change Liverpool? We're still, I hope, the city capable of creating something else.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.