Recent features

Public Art is Dead. Long Live Culture.

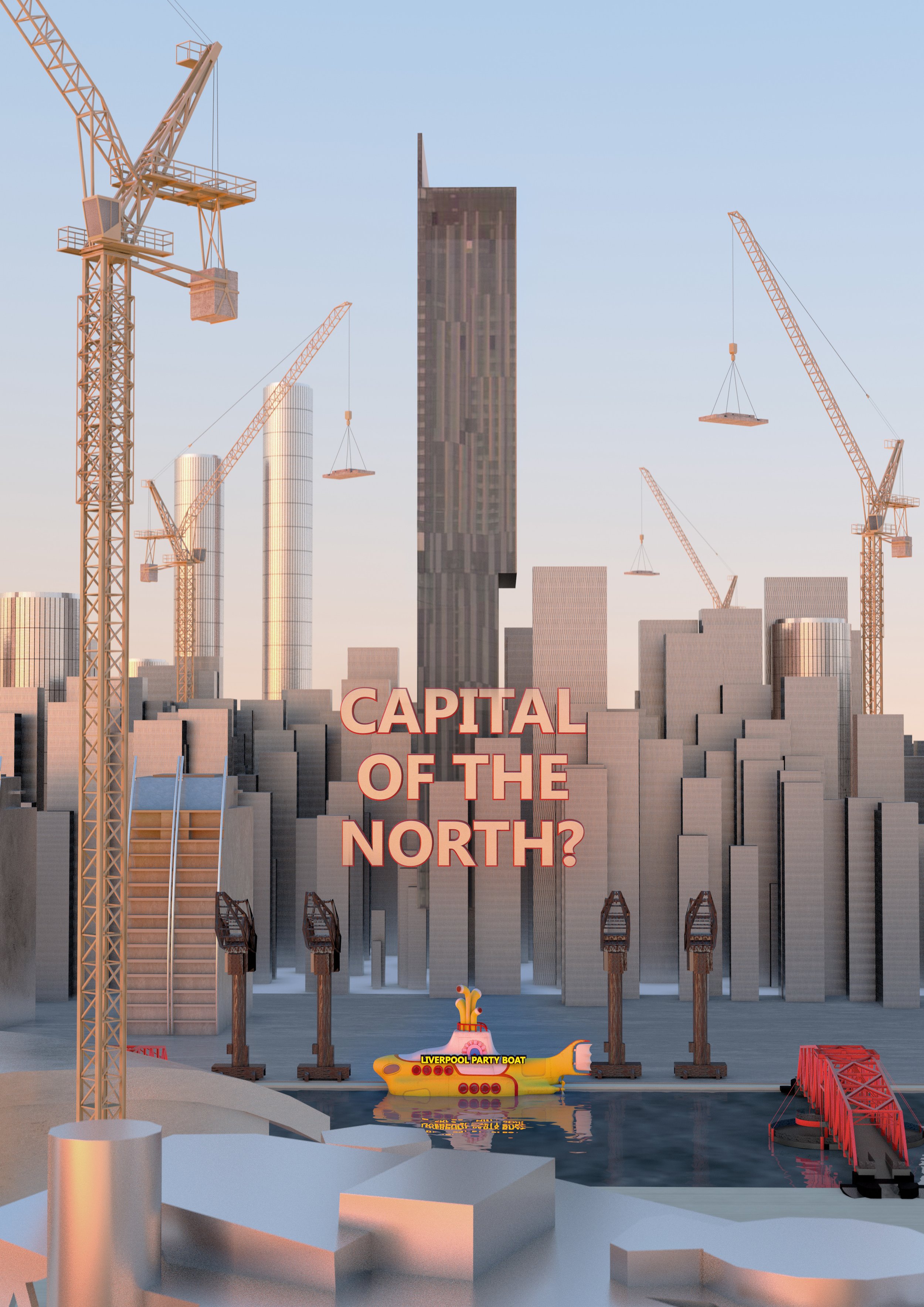

Liverpool has a complex relationship with its Art. Priding itself on its cultural credentials and home to the Liverpool Biennial art exhibition, yet its institutions tend to measure Art’s value in the spreadsheet metrics of the philistine. As our publicly commissioned pieces become ever more disposable, sanitised and inoffensive, art historian Ed Williams asks whether Liverpool is the place where art comes to die?

Ed Williams

Fifteen years have elapsed since Liverpool was honoured with the title European Capital of Culture, and with the help of constant repetition, the city’s status as a ‘Cultural City’ has been cemented within the popular consciousness, at least locally, if not always universally. But what, if anything, does this accolade mean today? And how do we stop it being just a meaningless marketing label, presuming it was ever more than that to start off with?

Culture, or at least a certain type of culture, is like universal health care and compulsory education often viewed as an indisputable social good – a life enhancer that with official state sanction became a defining feature of Britain’s Post-War project to improve the lives of its population. But culture is an elusive quarry - challenging to define, let alone to quantify within a framework of metrics. Unlike healthcare, culture does not ‘treat’ or ‘heal’ in a way that lends itself to spreadsheet evaluation. Nevertheless, a consensus of bien pensantism has coalesced around the importance of culture, invariably focusing less on its intrinsic and frustratingly wishy-washy, hard to define benefits and more on its ability to generate economic returns – something our civic leaders and purse-string holders can feel confident about putting on a press release. As a result, we’ve all become familiar with hearing how some new cultural initiative will add value to the local economy increase visitor spend, improve hotel occupancy rates, and create and sustain those all-important X number of jobs. We understand why these arguments predominate, but accusations of philistinism aside, the true purpose of culture seems to lie elsewhere.

These statistics, often quoted as culture’s most manifest benefit, highlight a fundamental point. In Britain’s post-industrial society, culture is increasingly what economic output looks like. The service sector is the prime employer, and culture is a branch of this sector. That’s why the leaders of our cultural institutions increasingly seem to resemble business men and women rather than merely champions of the arts. Or at least, they certainly have to moderate their artistic passions behind drier, more utilitarian language. The managers of a museum or art gallery may have more in common with that of a hotel or restaurant than is perhaps initially recognised, being equally concerned as they are with customer satisfaction, visitor throughput and money spent.

“A consensus of bien pensantism has coalesced around the importance of culture, focusing less on its intrinsic and frustratingly wishy-washy, hard to define benefits and more on its ability to generate economic returns.”

What one could colloquially call the ‘Cultural Economy’ argument may then explain the need among those, both in government and in the arts, to continually re-iterate the significance of Liverpool’s cultural status. After all, if we weren’t so economically desperate, perhaps there would be more willingness to talk about culture in its own terms and less need to worry about the financial side-benefits? In the absence of much else to shout about, continuously asserting the city’s cultural status becomes a proxy for saying we’re still here, we’re still relevant, we still have a future. It’s also jolly useful for any politicians keen to show they are making good decisions in a challenging environment.

Despite this, the inquisitive might well ask if this is all there is to ‘Culture? Is there anything beyond the reductivism of the bottom line? And if there is, how do we gauge it?

Beyond hosting prestigious events such as the recent Eurovision Song Contest Final, more recent efforts to assert Liverpool’s cultural status appear to focus on the commissioning of works of public art, such as Alicja Biala’s Merseyside Totemy (2022) and, more recently, those unveiled as part of this year’s Liverpool Biennial, including Rudy Loewe’s The Reckoning (2023) and Nicholas Galanin’s Threat Return (2023). These totemic pieces, no pun intended, now seemingly serve as cultural barometers through which our city’s cultural status appears to be discerned. Behold people of Liverpool, this is culture!

Black Power. Exploring ‘hot’ issues in inoffensive ways. Rudy Loewe, The Reckoning, 2023. Photograph by Rob Battersby, courtesy of Liverpool Biennial.

The result of this approach is an ever-increasing amount of public art on display. Whilst prima facie positive, the fact remains that the burgeoning number of works is so great, it is becoming an increasing challenge to maintain an accurate count; and to attend to their continued preservation and maintenance. But then maintenance no longer seems to be part of the brief.

Instead, in an Age of Austerity, public art is commissioned, paid for, put on display for a short time, and there the liability typically ends, with the item often all too swiftly packed up and removed to some mysterious warehouse/bonfire in the sky as if it never really existed – outside of a few pictures on the internet. This is Art transformed into fast moving consumer goods, less a vision for the ages cast in marble and more a plastic bag flapping in the wind. This hard-nosed economic reality may well explain why so many of the recent commissions have only a temporary status within the city. For example, as things stand, Alicja Biala’s Merseyside Totemy will be removed at some point in 2024.

Could this new approach to a work’s lifespan be a consequence of the fact that older pieces have been left to their own devices? Betty Woodman’s Liverpool Fountain (2016) looks to be in a forlorn state, with water flowing only occasionally. Stephen Broadbent’s beautiful and powerful Reconciliation (1) (1990) is blighted by the twin plagues of graffiti and adhesive stickers.

“In an Age of Austerity, public art is all too swiftly packed up and removed to some mysterious warehouse/bonfire in the sky as if it never really existed. This is Art transformed into fast moving consumer goods, less a vision for the ages cast in marble and more a plastic bag flapping in the wind.”

A cynic might surmise that this is an attempt to manifest ‘culture on the cheap’, far removed from the initial spirit with which Public Art was originally conceived in the immediate Post-War period. These works from the 1950s and early 1960s, originating at a time of greater optimism, represented egalitarian attempts to bring art to the wider public, away from the confining and often restrictive environs of museums and galleries. Typically, it was art designed to uplift the spirits. This was how the work of Moore, Hepworth, Epstein and Paolozzi, amongst others, became better known and appreciated by the non-gallery attending public. It was this zeitgeist of civic ambition and new hope that Jacob Epstein sought to depict in his iconic Liverpool Resurgent (1956) which still stands proudly defiant above the main entrance of the former Lewis’ department store. Later works such as Richard Huws’ cheerful kinetic sculpture, the Piazza Fountain(1967), more commonly known as the ‘Bucket Fountain’, were attempts to create a sense of place in an otherwise rather anonymous space. This second generation of works, beginning in the late 1960s, were also conceived as catalysts for development, particularly during the economic dark days of the 1980s and 1990s. They may be considered as examples of the role of public art in regenerating neighbourhoods and communities. Superlative pieces such as Charlotte Meyer’s Sea Circle (1984) and Tony Cragg’s Raleigh (1986) are stand out examples of British Postmodern sculpture at its best.

Cryptic. Visualising climate data to make it ‘accessible’. But can you trigger a conversation if no-one knows what you are talking about? Alicja Biala, Merseyside Totemy, 2022. Commissioned by Liverpool Biennial & Liverpool BID Company. Photograph: Ed Williams.

In more recent years, works have been commissioned by various bodies, including the Liverpool Biennial and Liverpool BID Company. Such is the abundance of these new works it would appear each year heralds at least one new unveiling. But is this merely art for art’s sake? Or does this reflect a wider desire to decorate the city with public art and thereby turn the urban environment into an open air gallery of temporary works? Whatever the motivation, the result appears to be a confusing array of pieces, revealed with some fanfare and then seemingly allowed to decay through neglect or indifference. The casual observer could be excused for concluding that Liverpool is a city where public art comes to die, discarded and left as litter like so many broken domestic appliances. Is this seeming lack of care evidence of a wider malaise within Liverpool’s cultural sector? Is it a failure to fully appreciate that a cultural legacy necessitates ‘after care’? Or does it merely reflect a changing view of art as temporary and disposable? Perhaps we no longer feel able to commit to ideas in the same way – our art like our views increasingly contingent and subject to new interpretations. Are older works, such as Carlos Cruz-Diez’ Induction Chromatique a Double Frequence pour L’Edmund Gardner Ship (2014) – that remarkable dazzle ship - now mere historic footnotes? Having been re-painted, all that remains of Carlos’ work is a small weather beaten placard. I can’t help wondering whether our seemingly endless obsession with the ever elusive avant garde, makes consideration of the established, the old and the familiar now anathema?

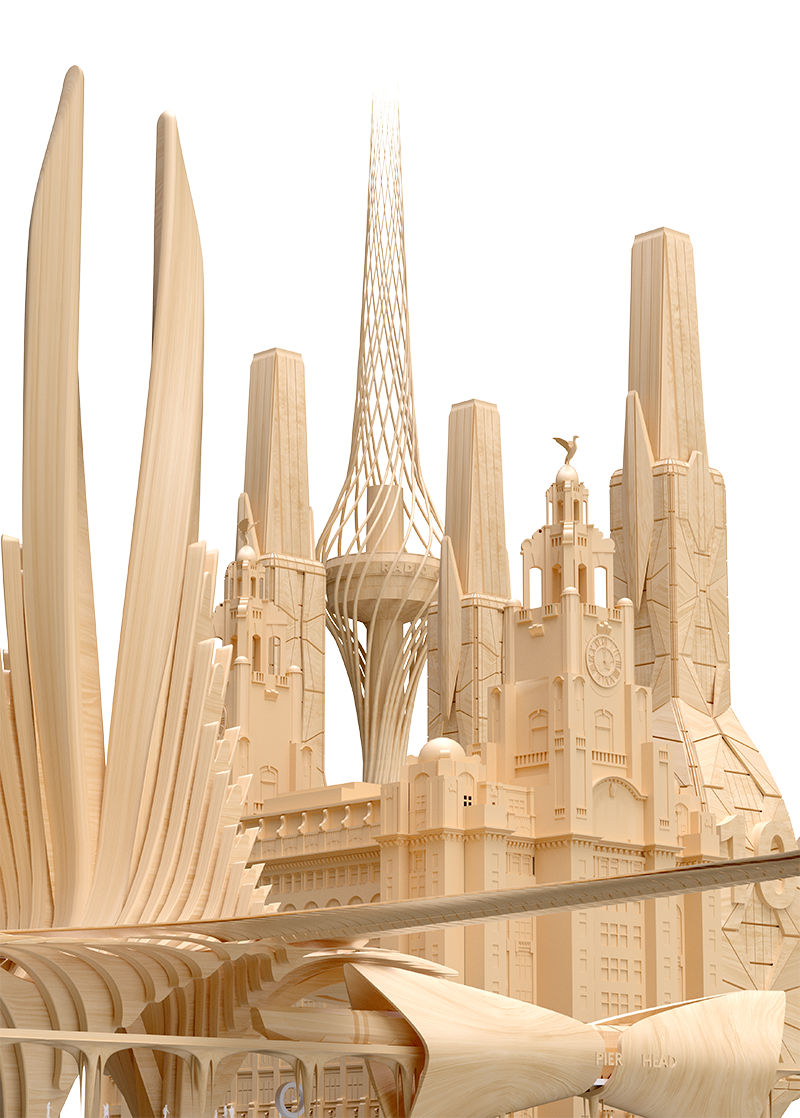

This focus on the temporary and the cheap may be the avowed intention of those who commission Liverpool’s contemporary public art, but a critical eye cast over recent works would conclude that they offer little to truly spark the imagination. These pieces provide not the ‘shock of the new’, but rather a dull blandness, resulting in a series of indifferent works which seemingly seek to please only the passing tourist and the selfie hunter. Consider for a moment, Ugo’s Liverpool Mountain, a vertically stacked tower of candy coloured stone blocks placed prominently at the Albert Dock. Whilst initially amusing, and you could argue eye-catching against the uniformity of the dock’s red-brick warehouses, it hardly moves one to further contemplation. But perhaps more importantly in a clear nod to modern sensibilities, neither does it offend anyone. This is Art as Entertainment. Seen, consumed and then forgotten.

“The dissonance between the pretensions of the explanatory labels and the works themselves is a gaping chasm. Alicja Biala’s sculptures are supposedly an attempt to visualise climate data, but you can’t spark a conversation if no-one knows what you are talking about.”

Even commissions which claim to have a more intellectually challenging agenda often fall short. The current Liverpool Biennial includes pieces which address hot button concerns such as race relations, social inequality and climate change, but these works only explore these issues in the most convoluted or inoffensive ways, often leaving the viewer unengaged, bemused or, at best, just happy to have themselves photographed next to a decorative work. The dissonance between the pretensions of the explanatory labels and the works themselves is a gaping chasm. Alicja Biala’s 2022 piece, Merseyside Totemy is a case in point. Only by reading the artist’s explanation or some earnest review in the nationals could you guess at the message. These sculptures are supposedly an attempt to visualise climate data, which we are told can often seem too ‘academic and theoretical’. But au contraire – they are the very example of clarity compared to these cryptic albeit pretty land buoys. You can’t spark a conversation if no-one knows what you are talking about.

Eleng Luluan’s, Ngialibalibade to the Lost Myth, 2023 is highly decorative but does it challenge the mind? Photograph by Ed Williams.

Rudy Loewe, The Reckoning, 2023 is another example of an attempt to make a serious point in an inoffensive way. Rudy’s original work was a far more powerful meditation on the injustices of British colonialism and a celebration of the 1970 Black Power Trinidadian Revolution. Yet this Biennial piece with its pink, orange and cyan stilt walkers just looks ‘funny’. But perhaps the award for the least engaging work should go to Eleng Luluan with her Ngialibalibade to the Lost Myth, 2023. According to the official spiel, ‘Ngialibalibade’ describes ‘the growth of life, the transformation of the soul, the change in nature, the rapid development of technology, the noticeable changes in life, or the subtle ones hiding in our hearts.’ Make of that what you will. It’s claimed the work has something to do with landslides in Taiwan and their power to upend ‘culture’. Though why culture rather than life should be emphasised is curious. Either way, its pottery jar made of fishing nets is remarkable more for its decorative qualities than its ability to provoke meditation on humanity’s relationship with nature. Still, at least it helps to mitigate the torpor elicited by the architecture of Princess Dock.

Surely culture must mean more than this? If the power of art stems from its ability to move, provoke or encourage us, then it must do more than merely act as decoration. Does this malign trend towards the banal and the superficial herald the craven surrender of those in leadership roles within the city’s cultural institutions to eliminate the alleged activism of art? Is this a reaction to the supposed ‘culture wars’ so obsessively reported on by the political right? Or can public art now only ever be commissioned if it is considered ‘safe’, inoffensive, and non-challenging? A small number of indifferent pieces may be forgiven, but the sheer abundance of such bland works seems anathema to the professed aims of public art.

“Perhaps we no longer feel able to commit to ideas in the same way – our art like our views increasingly contingent and subject to new interpretations.”

Forlorn. Betty Woodman, Liverpool Fountain, 2016. “The casual observer could be excused for concluding that Liverpool is a city where public art comes to die.” Photograph by Ed Williams.

I challenge those that cling to the illusion, with respect to public art, that ‘more is more’ in perpetuating Liverpool’s status as a ‘Cultural City’. Just as the European Union’s ever expanding list of cultural capitals – now an increasingly unexclusive club of 78 - tends to devalue the idea of the exceptional, so Liverpool must pay greater heed to what is valuable or risk swamping the quality it does possess in a sea of disposable superficiality. Or worse, lose its ability altogether to distinguish between what is good and what is not. If it is to be more than just an empty slogan, being a cultural capital should act as a rallying call to better appreciate the truly wonderful works we have and to consider commissioning pieces which truly reflect the dynamic power of art.

This is not an argument for ‘less is more’ – rather an entreaty to maintain the important works of public art that we already possess and to focus new commissions on truly ground breaking and lasting works for the people of Liverpool. This should be the real legacy of our City of Culture status.

Ed Williams is an Academic Art Historian who works for TATE Liverpool in the Visitor Experience team. He is a member of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA) and he teaches the History of Art at the University of Liverpool.

Ed is currently running a 5-week course at the University of Liverpool entitled 'How to Understand Art' starting in October 2023. For more details on enrolment click here.

Main image: Ugo Rondinone, Liverpool Mountain (2018). Photograph by Ed Williams.