Recent features

The Scourge of Northwesternism

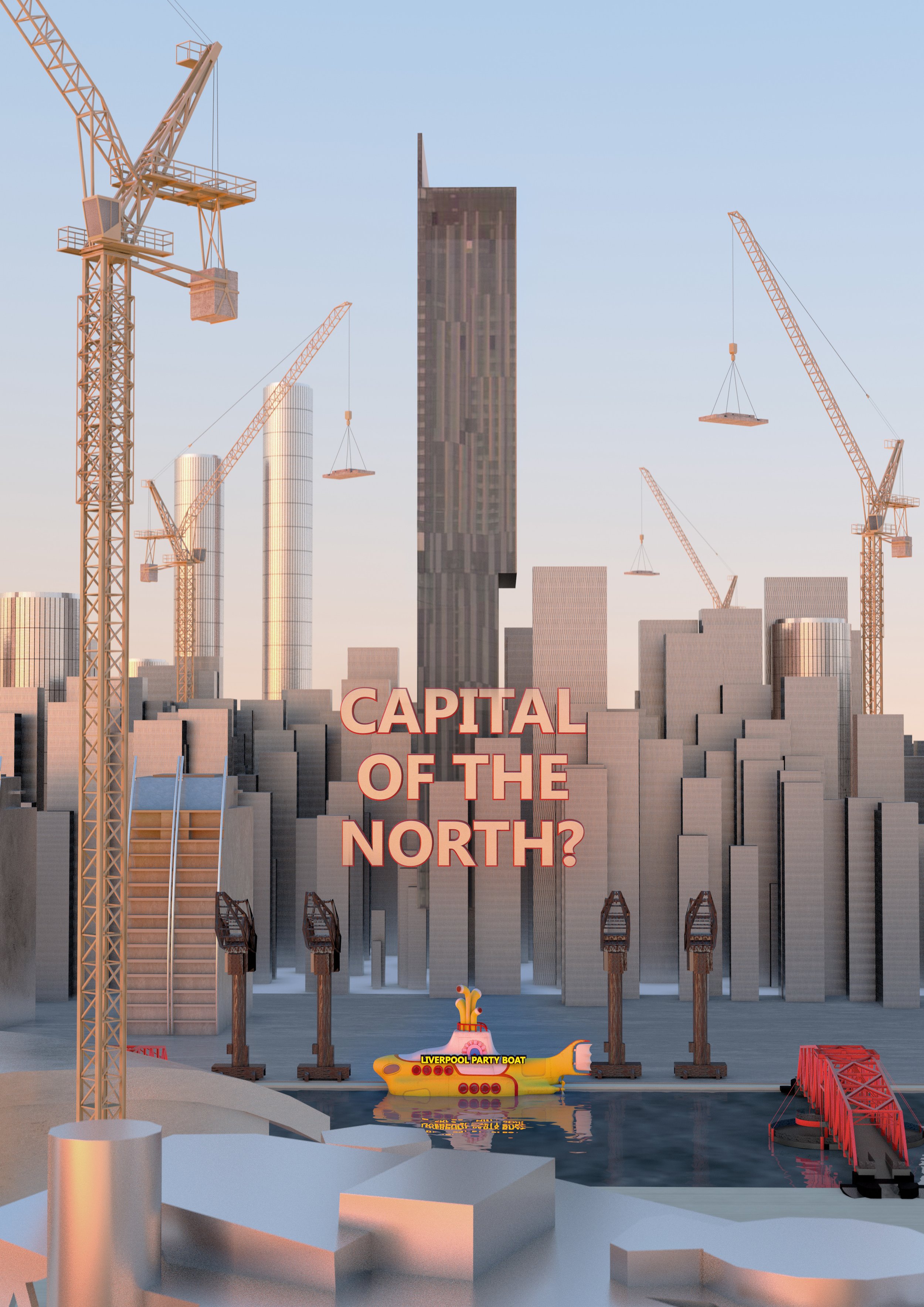

In England’s Northwest, one city blooms while another withers on the vine. Manchester is reaching for the skies while Liverpool stares at its navel. A cancerous rot is eating away at my city’s self-esteem. It deserves a name. I call it Northwesternism.

Michael McDonough and Paul Bryan

Does anyone else notice that simmering sense of defeatism running through pretty much everything Liverpool does today? Whether it’s politics, culture or architecture there seems to be a crushing sense of meekness dragging down or at the very least blowing off course the city’s regeneration. You don’t have to look too far to find the evidence, from Liverpool’s proposed new stumpy, tall buildings policy, to the attempts to rejuvenate the high street with low-class tat like bingo and go-karts. Even our waterfront indoor arena was built patently too small to compete for the best music acts. We seem to have gotten good at hiding ourselves under a rock.

I noticed this sense of defeatism running through what was otherwise a riveting read by Jon Egan in his recent Liverpolitan article, ‘It’s Time to Get Interesting’. Examining Liverpool’s fallen place in the world, he searched for a solution and built it on the stoniest ground. Believing that “Liverpool’s claims to regional dominance is a boat that has long since sailed”, he called it an “unavoidable truth” that Manchester is now established as the region’s capital. Then from that premise he pitched an idea - unable to escape our fate as the North West’s second fiddle, we should lower our goals and find a workaround based on our outsider status and our sense of difference. He suggested we do this, by making ourselves ‘interesting’, something that comes naturally to us because it’s kind of in our social DNA. Austin, Texas was held up as a possible model to follow, a city which carves out its place in the world under the banner, ‘Keep Austin Weird’.

Now, I know that Jon doesn’t intend to cast Liverpool as a dancing monkey at a freak show, and you could argue that the economic data points to the truth of our cities relative position, but I don’t really see this strategy solving the myriad economic and social problems that Liverpool faces. It doesn’t sound all that far removed from the innovation strategies that have largely failed to deliver innovation. But my biggest problem with it is that it’s premised on pessimism. For me the race to become interesting or to live into our sense of cultural difference is just a way of rationalising our lowered position.

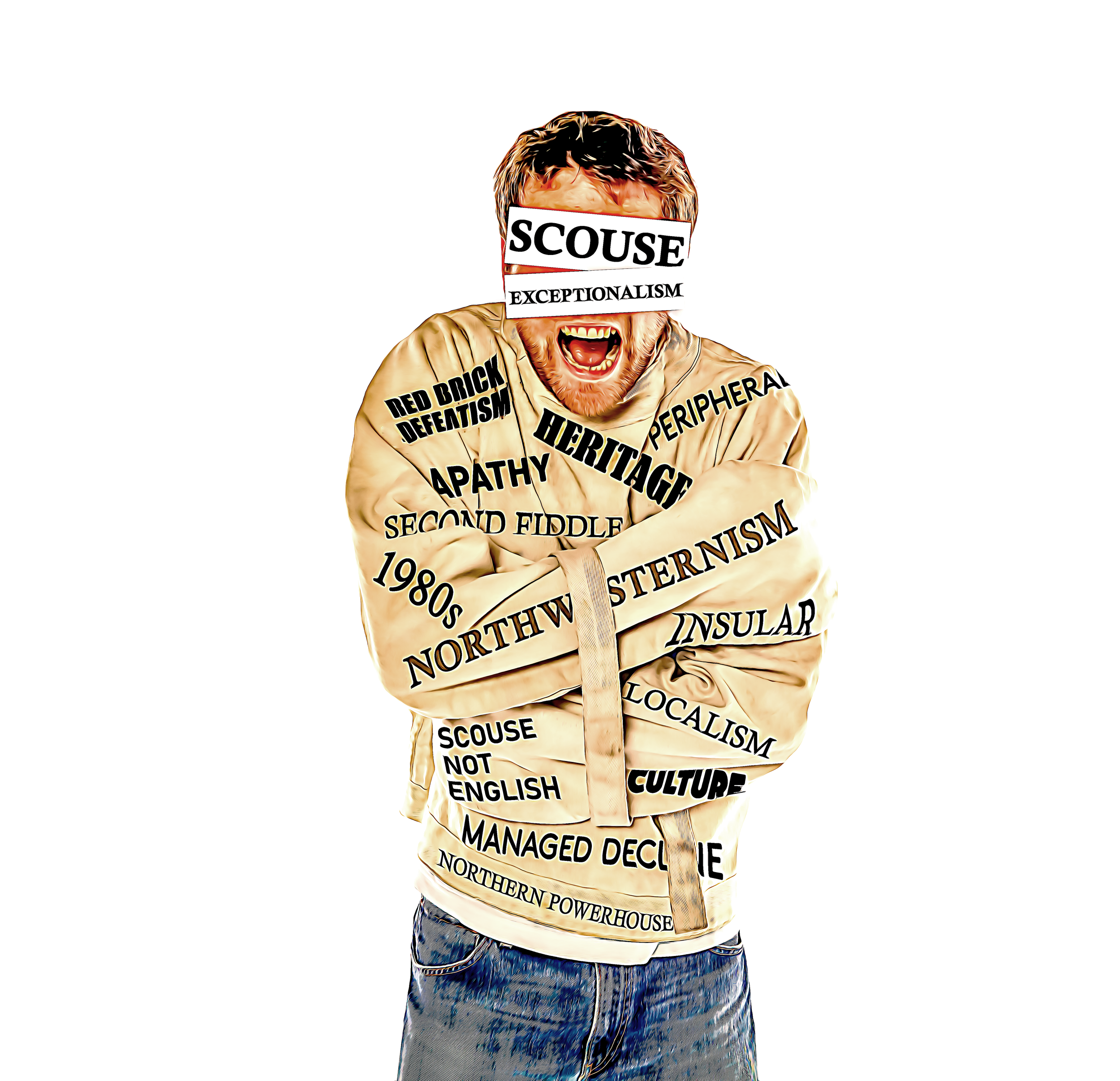

For me this all smacks of a cancerous rot eating away at Liverpool’s self-esteem. A long gestating idea that Liverpool cannot and will not ever again be more than an offshoot of the aspirations of another relatively small, regional UK city. Who the hell wants that? It’s a view that forces us to lower our horizons and settle for less and it has only one direction of travel - from city to village in countless, tiny steps.

Manchester at night. Just down the road things looked a little different. Chris Chambers / Alamy

I’m sad to say I increasingly see evidence of this sense of cultural pessimism all around me. They say, make no small plans, but we’re becoming experts at it, and you’ll find a whole breed of shamanistic professionals, activists or NIMBYs throwing shade on the very idea of planning big, going tall, and growing our economy. Sometimes they even reject the very concept of competing. This low growth rationalisation of defeat is usually wrapped in warm fuzzy words like sustainability or human-centred development, while a more optimistic view is seen as foolishly utopian or an apologetic for predatory capitalism. Yet just a few miles down the road things look quite different. And for those who want more, it’s often easier to just pack their bags and relocate.

Too much of our professional class appears to have succumbed to the Liverpool-killing long game of ‘regionalism’ - the modern face of managed decline. You can hear it in the language, and see it in the initiatives. It’s almost as if a subconscious decision-making 'culture' has pushed Liverpool to the periphery. Seeing yourself as secondary or even tertiary is now so ingrained that Liverpool no longer feels it can compete with what is merely another UK provincial city. So instead we see attempts to 'partner', 'work with’ and ‘align with’ Manchester-based institutions, which feels more and more like surrender rather than balanced cooperation.

Of course, ego won’t let us admit this and any self-respecting scouser will bristle at the very idea of Manchester as the regional capital; dark insecurities soothed by talk of world-class this and world-class that. Perhaps if we host Eurovision we’ll feel relevant again? But it doesn’t mean this humbling process isn’t happening or hasn’t already happened right under our noses. It’s all part of the perpetual grind of what I call ‘Northwesternism’. It’s part policy and part psychology – the forces of economic agglomeration, and political influence colliding with the endless boosterism of a perpetually on the front-foot city, culturally pump-primed by a media only too willing to play along. Drip, drip, drip bleed the jobs and opportunities; young lives transfused away. On the Liverpool side, we put the blinkers on, our taxi drivers famed for telling all and sundry ‘things are getting better’. Do they still say that? Over time, our inferiority complex becomes so ingrained that when the subject of the problematic Liverpool-Manchester relationship is brought up it’s laughed at or sneered at, dismissed as some kind of conspiracy theory. But then you just have to look at our graduate retention numbers. Deep down we just know.

“The idea that our two cities, separated by a mere 32.9 miles are not in competition with each other is a supreme act of gaslighting.”

Anthony Murphy of the University of Liverpool Management School recently posted on Twitter that “Smart young people from the city see it that way - flocking there for decent, well-paid jobs”. He wasn’t talking about Liverpool. Sometimes, being the capital is a state of mind. They have it, we don’t and they have the jobs too.

Our subconscious defeatism makes us smaller, lesser and this shows across so many sectors. We've almost got Stockholm Syndrome. I believe that Liverpool's malaise and rudderless direction have been a wonderful gift to Manchester's leaders creating a workforce that only ever travels east in the morning.

‘Northwesternism’, the passive acceptance that Manchester is the region’s dominant Silverback, is for me Liverpool’s greatest challenge in re-asserting itself as a major city. Our leaders should go into every regional partnership meeting with their eyes open, asking themselves ‘what’s in it for us?’ In Jon Egan’s article, he discussed how ‘Manchester is definitively and inexorably set on its own northern trajectory’. That being the case, why on earth does our Metro Mayor Steve Rotherham continue to insist on working so closely with Manchester’s Mayor, Andy Burnham? They have their own trajectory and set of goals, and they are not the same as ours. Increasingly, it feels to me as though Andy Burnham is entertaining one of the Greater Manchester boroughs – once Liverpool, now Manchester-on-Sea.

Do a little research and you’ll discover Mr Rotheram more often than not is stood behind Andy Burnham in public images and media features. Burnham is always positioned at the centre. There are no calls for Rotherham to be christened the ‘King of the North’; no bets placed on Steve Rotherham to be a future Prime Minister, and certainly no column in the London Evening Standard. You could ask why any of this matters, but in an era of image and soft power projection, Liverpool is suspiciously absent from the national conversation, a recommended city break in the Telegraph, but fringe where it counts.

Until Liverpool rejects ‘Northwesternism’ and the slow but steady spread of Manchester’s well-oiled and expanding ‘psychogeography’, then Liverpool cannot confidently look outward to the rest of the world as it will be forever undermined on its own doorstep.

I think we have to wake up and fast. And now Levelling Up Secretary, Greg Clarke, has just invited Sir Howard Bernstein, Manchester City Council’s former Chief Executive to help draw up a vision for our city’s future, something our own council has singularly failed to do themselves. He’ll be joined by Judith Blake, former Leader of Leeds Council, Steve Rotheram and an as yet unnamed person from the business sector. Excellent administrators though they are, I can’t help wondering if Howard and Judith will have Liverpool’s best interests at heart. Maybe they will. We can hope for the best. Would Bernstein propose anything that might weaken Manchester’s grip given he spent his whole career building their success? Would he want to champion our promising games industry or eye it as yet another prospect to wine and dine? Would Judith support a significant expansion of our legal sector given Leed’s strengths in that area? At the very least, we need to stay awake to our own interests at all times and turn a deaf ear to those who say competing is for chumps – that Liverpool can exist in its own utopian bubble where the lion lays down with the lamb.

“This low growth rationalisation of defeat is usually wrapped in warm fuzzy words like sustainability or human-centred development, while a more optimistic view is seen as foolishly utopian or an apologetic for predatory capitalism.”

MANCHESTER nakedly pursues its own interests. There’s nothing wrong with that – I’m not passing moral judgement but the idea that our two cities, separated by a mere 32.9 miles are not in competition with each other is a supreme act of gaslighting. The fact that so many members of Liverpool’s political and business communities have fallen for it, like hostages besotted with their kidnappers, is evidence of either a stunning lack of self-awareness or a cynical judgement on moving as the wind blows, taking advantage of a new reality while tucking the loser in bed and whispering in their ear that everything will be alright.

The decision in 1997 to approve Manchester Airport’s second runway over expansion at Liverpool was not in our interests. It was in theirs. The building of Media City in 2007 with its gravitational pull on all TV production led to the closing of our own Granada TV Studio at Albert Dock. It was not in our interests. It was in theirs. The conscious derailment by the Greater Manchester Combined Authority in 2012 of the Atlantic Gateway strategy which would have seen multi-billion pound investments along the Ship Canal land corridor including at Liverpool and Wirral Waters was torpedoed in favour of a focus on city regions and what became the Northern Powerhouse with the cheques signed off in George Osbourne’s Tatton constituency. It sank the prospect of region-wide regeneration in favour of the city to the east. It was not in our interests. It was in theirs. The decision to build two gold-plated HS2 stations in Manchester and Manchester Airport (and none in Liverpool), given the nod in 2013, meant an unnecessary dog-leg and longer commutes between the cities. It was not in our interests. It was in theirs. Not that Joe Anderson would have noticed. He was like a blind man in a room full of alligators. Food for the predators. But the piece de resistance dates back to 2001 and the signing of the hard to believe Manchester-Liverpool Joint Concordat Agreement by the leaders of the two cities under the watchful eyes of the then Deputy Prime Minister, John Prescott and the supposedly neutral North West Development Agency. Inspired by a Salford University academic, the agreement proposed to end our ancient enmity once and for all. As noted in the Independent, the Concordat bluntly concluded that Manchester was the "regional capital" and there is "little sense in Liverpool seeking to challenge that reality". It must have been hard to suppress the sniggers. Whole industry sectors were carved out for non-competition, the kind of ones that generally required office space and high paying skills. Liverpool’s “unique attributes and distinctive economic strengths” won it tourism and culture, and then Manchester, with a belly full of everything else, went after that anyway with its £114m government funded Factory arts venue and it’s Art Council supported Manchester International Festival. Needless to say this sorry document - the Joint Concordat - was not in our interests. It was in theirs. That a Liverpool Council Leader – Lib Dem, Mike Storey, saw fit to sign such a blatant sell-out of his constituents’ futures shows that he was nowhere near as clever as he thought he was. He was played pure and simple. Either that or he had a masochistic streak, though the fact he ended up in the House of Lords suggests he wasn’t the one feeling the pain. The story doesn’t end there of course – the drip, drip, drip of consequence – of capital and talent continuing to haemorrhage away. Companies like Castore, Redx and Biofortuna. The grass definitely greener on the other side.

I can’t condemn Manchester for acting in its own interests. I just want the same for Liverpool. I want us to wake up to our interests. To fight for them and to have the good sense to know when we are being had. To stop being a patsy. To stop playing the fool. Talk that cities don’t need to compete is fitting of the dunce cap and I think we’d all prefer to wear more desirable head gear.

“That a Liverpool Council Leader – Lib Dem, Mike Storey, saw fit to sign such a blatant sell-out of his constituents’ futures shows that he was nowhere near as clever as he thought he was. He was played pure and simple.”

The recent spat between local councillors and developers at Waterloo Dock was a symbol of another fine mess we’ve built for ourselves – another expression of Liverpool’s ability to trip on its own feet. Amongst the general rot and dereliction, we built a complex nest of low aspirations to house not Canada Geese, but local representatives, who like squawking chicks pretended their advocacy of ‘blue space’ was a defence of high aspiration and ‘world-class’ heritage. That phrase again. It was nothing of the kind.

The enraged opposition to the development of what is to any sane person a piece of wasteland was deeply embarrassing to watch. Frustrating attempts to encourage inward investment, councillors cronied up to self-interested NIMBYS who were out to protect their own river views. In doing so, they further entrenched an anti-capitalist, ‘scousers versus the world’ mentality. By pitching local people against ‘greedy developers’ and roping in heritage ‘concerns’, they found a new way to frustrate Liverpool’s aspirations, and in the process convinced some poor sod from the Planning Department to embarrass himself at the appeal. Thankfully on this occasion reason won out and the determined developer won the day. I suspect we’re wiser to their tricks now. The ‘build nothing’ types will find it harder to play their games in the future.

Rabbits were suddenly ‘discovered’ in Bixteth Gardens by campaigners against an office development. Photo by Gavin Allanwood on Unsplash

Even with the Waterloo Dock development getting over the line, there does seem to be a sense of red brick, low-rise defeatism in the city’s modern architectural landscape. Where cities like Manchester and Birmingham go big, Liverpool has managed to shroud its lack of urban aspiration in a thin veil of heritage and ill-informed talk of ‘human scale’. While Manchester and other progressive cities throw up new developments like confetti providing new homes, jobs and office spaces for international companies, Liverpool’s local councillors, like Labour’s Nick Small, shamefully protest against developments such as Pall Mall, a long overdue project to bring Grade A office space to a city that has one of the smallest portfolios of commercial floorspace in the country.

Why did the protesters object? Rabbits. Now I’m all for the protection of wildlife but the former Liverpool Exchange station site is not the setting for Watership Down. I’d much rather see our public institutions looking to attract companies out of rival conurbations and into our own central business district, incentivising them to base in new, large-scale, glass, brick and steel office blocks. But that sounds too much like hard work. I guess it’s much easier to rationalise doing nothing by weaving an almost religious acceptance to it. Building is for other cities, it’s not for us. We have another vision. What is it? Don’t know.

What Liverpool needs desperately is to find leaders in business, politics and the community who are unashamedly ambitious. But what does that ambition look like? Ambition and aspiration for Liverpool should be in the form of a real, tangible plan to re-position the city at the forefront of northern politics and to openly and confidently shun any notion of northern capitals in Manchester. In fact, I would suggest making it a core strategy to pull as much investment, business and talent away from our northern neighbours and London as is humanly possible. Let them know they are in a fight. We Come Not To Play. Liverpool gains next to nothing from ‘collaboration’ with Manchester, never has and never will. If anything, in our naivete we are just helping to reinforce this self-defeating status quo.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

It’s Time to Get Interesting

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to Manchester’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

Jon Egan

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to the city’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

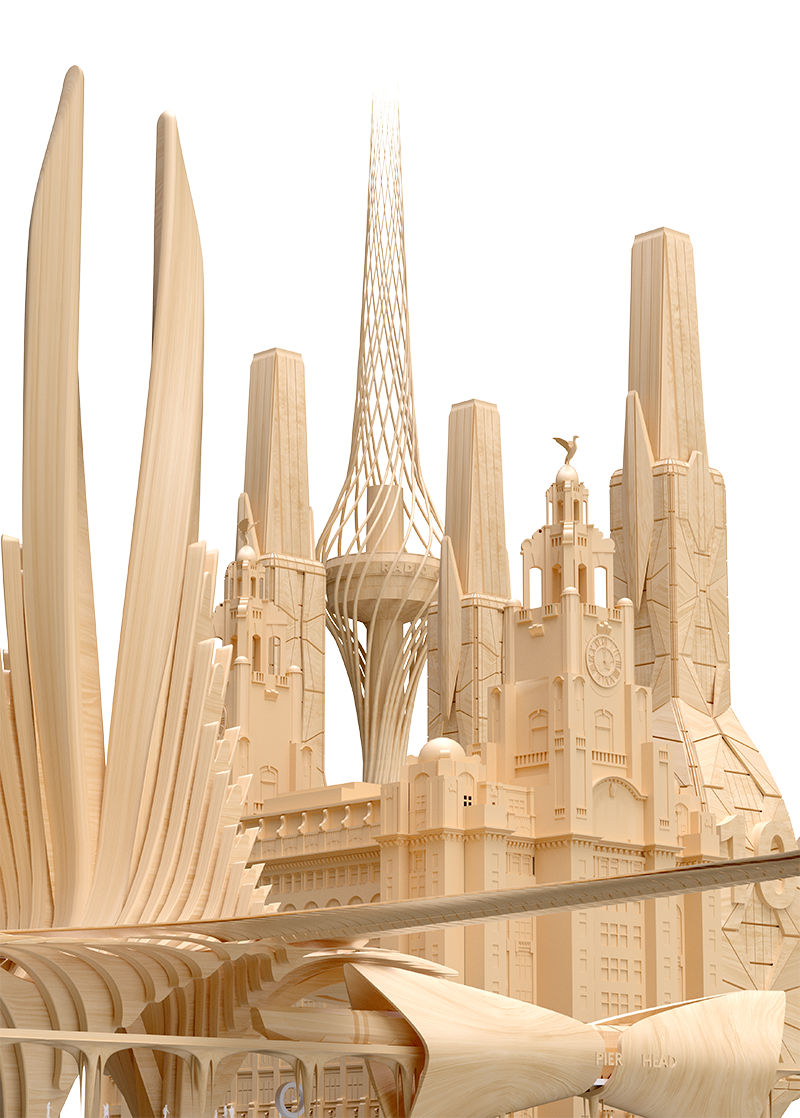

This long-forgotten televisual gem was brought to mind by a recent tweet from Liverpolitan which observed, sagely, that when Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of his own city’s expanding psychogeography. Under Burnham’s monarchic reign, Manchester has become the fulcrum of an aspiring northern nation. Its status as capital of the north is beyond dispute. Michael McDonough’s visionary prospectus for Liverpool’s Assembly District as a home for pan-northern regional government (beautiful and inspiring though it is) is destined to remain another sadly lamented ‘what if’. Liverpool’s own claims to northern dominance are a boat that has long since sailed and, like a great deal of our city’s historic wealth and prestige, are now securely moored at the other end of the Manchester Ship Canal.

Sorry if this sounds fatalistic and defeatist, but it’s an unavoidable truth. Manchester as regional capital has already happened and I can’t help feeling it’s actually entirely apposite. Liverpool is not, never has been and never will be the capital of the north for a very simple reason - we’re not in ‘the North.’

Let me explain. Some years ago when pitching for the brief that became the It’s Liverpool city branding campaign, my agency team and I presented an extract from a speech by then Tory Minister for Transport, Phillip Hammond. In it, he had been extolling the benefits of HS2, which he prophesied would unleash the potential of “our great northern cities.” To emphasise the point, and presumably to educate his London-centric media audience, he decided to identify these hazy and distant provincial relics that would soon benefit from an umbilical connection to London’s life-giving energy and dynamism. Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Sheffield, Bradford and even Newcastle (which wasn’t in any way connected to the proposed HS2 network) all made it on to his list. Our pitch focussed on Liverpool’s conspicuous absence from Hammond’s litany. We weren’t (as I opined in an earlier offering to this publication) ‘on the map’. We deduced that the speech was one more piece of definitive evidence that Liverpool wasn’t considered sufficiently great to merit a mention - nor important enough to be connected to a flagship piece of national infrastructure. But on reflection, there may have been another reason for the city’s omission. Perhaps we weren’t sufficiently northern! As if the inclusion of the offending syllables liv-er-pool would have somehow derailed this Lowryesque invocation of smoke stacks, cloth caps and matchstalk cats and dogs.

Of course, we are not talking about The North as a geographic region, or even an amalgam of richly diverse sub-regions, but as a mythic construct. However, as the French philosopher and founder of semiotics, Roland Barthes, would argue, myths are always distortions, albeit with powerful propensities to overcome and subvert reality. In this sense, northernness is not merely a point on the compass - It’s a complex abstraction, a constituent part of the English psyche and self-image that has strong connecting predicates and excluding characteristics. Geography alone is not enough to discern where The North begins and which enclaves and exclaves are to be considered intrinsic to its essential terroir. Isn’t Cheshire really a displaced Home County tragically detached from its kith and kin by some ancient geological trauma?

Thus when Government Ministers or London-based media commentators pronounce on "The North" they are all too often referencing a cloudy and amorphous abstraction defined not by lines on maps, but by indistinguishable accents, bleak moorlands and monochrome gloomy townscapes, nostalgically referred to as ‘great cities’. From this perspective, northerners are seen as honest, hardworking souls, who used to make things (when things were an important source of wealth and national prestige). Though stoical and resilient, they have a tendency, every generation or so, to get a bit bolshy, at which point it becomes necessary to reassure them of their place in our national life by relocating part of a prestigious institution to a randomly selected northern location, or by staging a second-tier sporting event such as the Commonwealth Games or perhaps even placating them with some vague commitment to ‘re-balancing’.

“When Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of Manchester’s expanding psychogeography.”

Manchester has been brilliantly adept at securing for itself more than its just share of these charitably dispensed national goodies. Largely that’s through a typically northern resourcefulness and pragmatism, but also because the city has ingeniously positioned itself as a shorthand synonym for the very idea of northernness.

Peter Saville CBE, the graphic designer who art-directed Factory Records and designed their most iconic album sleeves, also created the acclaimed Original Modern branding for Manchester in 2006. A predictably beautiful piece of graphic creation, it wove a vivid palette of cotton loom colours to represent a new Manchester, that was proud of its pioneering past but wanted to take that innovative DNA to recreate itself in the 21st century. It was wildly popular, but as an exercise in “re-branding” it didn’t succeed in challenging or reframing Manchester’s perceived identity. Instead, it merely set out to transmute it into something more contemporary and serviceable. Saville's project was to dig deeper into the Manchester’s vernacular version of mythic northernness, reflecting no doubt his immersion in Factory's overtly industrial aesthetic. It’s a restatement of core northern traits and a celebration of the city’s long-established narrative - the hub of the industrial north. Manchester’s sense of modernity was less about today and more an evocation of the 19th century, when it was considered the workshop of the world. Its originality was brilliantly expressed by the historian, Asa Briggs, who described it as the “Shock City of the age” - an urban phenomenon without peer or precedent in Europe and only matched by Chicago in North America. Cut forward to the early years of the Noughties. The opening of the ill-fated Urbis project – a new ‘Museum of the City’, conceived by Justin O’Connor and designed by Ian Simpson, was a bold assertion in shining glass and steel of Manchester’s boast to have been the world's first industrial city and the birthplace of the modern age. Despite the powerful statement of brand identity, it was a hopelessly unsuccessful attraction, closing after only two years in 2004. Its director candidly admitted that this monument to the city’s inventive and industrious spirit simply “didn’t work.”

Peter Saville’s Original Modern. Despite the fresh lick of paint, Manchester’s new branding campaign was curiously backward-looking.

In my article, Vanished. The city that disappeared from the map, I suggested that one radical option for Liverpool was to stop trying to compete with its eastern twin. Instead, I argued, we could become a new kind of urban entity - a city with two poles, which pooled our joint assets and balanced the two hemispheres of human consciousness to forge a global metropolis that could re-balance Britain without needing to turn to the patronising benevolence of London. Two hundred years after the building of the world’s first inter-city railway between Liverpool and Manchester, it seemed like a plausible and timely possibility to explore. I was wrong. Not because this idea is manifestly an anathema and heresy to every patriotic Liverpolitan (except me, it seems), but because Manchester is definitively and inexorably set on its own northern trajectory (even to the point where its most creative and happening urban district is aptly branded the Northern Quarter). Unlike Liverpool, Manchester's identity is embedded in its geography, and its literal place in the world. Its compass has only one co-ordinate and it isn’t west.

So where does that leave Liverpool? If we’re not part of The North, where in the world are we? Exiled and dislocated from our northern hinterland, we are a place apart; liminal and strangely detached from mundane geography. The recent media frenzy occasioned by the booing of the national anthem by Liverpool FC fans reignited a predictably shallow rehash of the “Scouse not English" debate, with the now familiar allusions to Margaret Thatcher’s alleged but never conclusively proven project to euthanize the city, compounded by the tragic injustice of Hillsborough. But these events were not the beginning of Liverpool's estrangement from its northern and English identity and its gradual drift to the edge of otherness. When in the second half of the 19th century our “accent exceedingly rare” began to emerge as something radically different to the dialects of neighbouring Lancashire, it was disparaged as “Liverpool Irish” - a vernacular that was deemed to be both alien and inherently seditious. As late as 1958, in Basil Dearden’s film Violent Playground - a British-take on the then topical theme of “juvenile delinquency” - the Liverpool street gang, led by a youthful David McCallum, are portrayed with accents that one reviewer of the DVD release, observed, “curiously owe more to the Liffey (Dublin's river) than the Mersey.” We were quite literally being depicted as foreigners in our own country.

Struggling to find a place within the recognised cartography of northernness, with a figure and stature too grandiose for the peripheral space allotted to us, where in the world can we find a comfortable and fruitful niche? The city that disappeared from the map has only one option - find a new map!

“Liverpool’s cultural programme is undoubtedly worthy, but how many people outside the city can name a single event, festival or programme that happens here?”

Let’s call it the map of interesting cities - places with an ingenuity and energy that is not defined by their geography, and whose confidence and chutzpah aren’t predicated on being the capital of anywhere or anything. Cities whose identity isn’t camouflaged or submerged into anything as nebulous as a region or a point on the compass. So let’s concentrate on being seriously interesting.

It’s a mantel that fits our self-image but we need more than the costume. It’s a project that demands a script and some serious acting. I genuinely think that Liverpool is an interesting city, it’s just that for too long we have marketed ourselves on the basis of our most boring and predictable traits.

We could take our cue from Austin, Texas, a city that markets itself with the slogan “Keep Austin Weird”. It based its civic renewal project on a determination “not to be Houston.” Austin’s promotion of independent business and cutting-edge creativity made it an early poster-child for Richard Florida’s boho-city thesis that diverse, tolerant and culturally cool metropolitan regions will exhibit higher levels of economic development. But Austin’s claim to be an interesting city pre-dates the self-conscious cultivation of weirdness as a kitsch merchandising gimmick. Austin devised and delivered what is now one of the world’s most prestigious gatherings of music, film and interactive media creatives at the annual SXSW festival. It’s an object lesson on how to make space for a genuinely international and seriously ambitious cultural proposition and use it to re-position and redefine a city.

Have we really built on the exposure of 2008 to deliver an internationally recognised programme of cultural events? For all the self-congratulatory posturing, Liverpool’s cultural programme is undoubtedly worthy, definitely diverse but how many people outside the city can name a single event, festival or programme that happens here? For all the energy and inventiveness invested in our pell mell of festive gatherings, we somehow manage to deliver a cultural calendar that is considerably less than the sum of its manifold parts. Places that use cultural events as the pivot for their positioning strategy generally do so by delivering one event or festival of genuine international scale and quality, as Edinburgh, Venice, Austin, San Remo, Cannes and Hay on Wye amongst others will testify. Similarly, “cultural cities” or UNESCO cities of music will normally look to validate that title with a programme that is commensurate with their claim or status.

I’m not going to predict or prescribe the event or theme that Liverpool needs to devise because there are bigger and better informed brains than mine who will be needed for that task. However, I do believe this city can build and sustain an international profile compatible with its brand and reputation by aiming higher and deploying its resources accordingly. For Austin, SWSX was not a travelling circus; it was an integral part of the city’s emergence from the shadows of Houston and Dallas to find its own profile and authentic magnetism. (For more information on Austin’s struggle to maintain its cultural identity try Weird City by Joshua Long).

Being interesting is a vocation. It demands creativity as well as rigorous discipline and hard work. It inevitably requires a style and quality of leadership that is absent from our dismal and discredited local politics. It’s ironic that the one aspect of our civic life that is without question unique and interesting, is so for all the wrong reasons. Liverpool's politics never fails to entertain, shock, frustrate and confound - if only it could achieve and deliver. In the 19th century, Liverpool not only spearheaded ground-breaking projects in rail, building technology and maritime engineering, we were also a wellspring for innovations in public policy and governance. Through pioneering initiatives like the introduction of the district nursing service and public washhouses, and the appointment of the world's first medical officer of public health, Liverpool's civic leaders responded to unprecedented challenges with entirely original structures and solutions. At a time when so many of the established prescriptions and paradigms are breaking down, we need to be plugged into the people and places that are responding creatively to challenges like climate change, technology & the future of work, life-long learning, democratic engagement or the next global pandemic.

Being interesting has to be a behavioural norm that finds expression across every sector and constituency. Are our politics interesting or innovative? Is our media intelligent and stimulating? Are we nurturing our most inventive businesses? Are we doing anything original or brave to address our challenges in education, housing or transport? How do we hope to stem the migration of talent, potential and ingenuity as too many of our best and brightest conclude that this city simply doesn't offer them a future? How do we emulate cities like Austin and become a magnet for innovators and entrepreneurs rather than a departure lounge?

Being interesting is fundamentally about being interested and connected to the wider world! It’s about being aware of what’s happening outside the insular and constricting straight-jacket of scouse exceptionalism or parochial northernness. It’s being open to outside influences and ideas and forging connections and relationships with kindred cities. Maybe we could become the convenor of the interesting city network - a global family of midsize cities free from the gravitational drag of conformity and contingent geography? Cities like Portland, Rotterdam, Hamburg, Auckland and Vancouver whose commitments to liveability and sustainability has sparked inventiveness in transport, urban planning, smart technology and the cultural industries.

If there is a common trait or attitude that connects these cities it is that they are porous, with a capacity and willingness to absorb ideas, influences and people from outside and beyond. Their thinking and ambition is not stunted by a perspective that is either provincial or parochial. They have a place in the world defined more by attitude and outlook than their position on the map. More often than not, they are ports and portals for cultural and human exchange. Auckland and Vancouver have flourished as a direct consequence of immigration, welcoming industrious and ambitious migrants from South Asia and East Asia. Despite our boast to be the World in One City, Liverpool is one of the least demographically diverse cities in the UK. Having at last stemmed our population decline, we are still growing at a discernibly slower rate than comparable cities like Leeds and Manchester. So let's grow our population by becoming an overtly immigrant friendly city, and proactively targeting one potential migrant population with whom we already have an historic and cultural affinity. Doesn't it make sense for the home of Europe's oldest Chinatown to be promoting itself as a welcoming haven for Hong Kong residents fearful of mainland China's increasingly despotic designs on the former colony? "Hungry outsiders wanting to be insiders" was a phrase coined by West Berlin in the 1980s as a strategy to reverse demographic and economic stagnation. It's an approach that a city built for twice its current population could usefully emulate.

Our new narrative can be built on familiar and cherished aspects of (or at least claims about) Liverpool's core identity - open, welcoming and global. But it's time to live them rather than simply intoning them as glib marketing slogans and nostalgic musings. Brands are about behaviour; their truth and utility is measured by what you do, not by what you say, so let's be consistently and ambitiously global not provincial.

In the same way that we need to rethink and curate our cultural programme to be genuinely international in terms of reach and quality, we should be enlisting global talent and expertise to help us rethink and reshape our city. Rather than flogging off prime sites like Liverpool Waters and the Festival Garden to whichever developer or volume house builder is offering the biggest buck, let's hold an international design competition to deliver the most innovative and sustainable new waterfront communities. Twenty years ago, Liverpool Vision was able to excite architects of the calibre of Richard Rogers, Rem Koolhaas, Will Alsop and Norman Foster in opportunities at Mann Island and King's Waterfront. It's a tragic shame that none of their inspired visions came to fruition, but let's resolve to try harder and be clear and consistent about who we are and how we intend to renew and reposition our city.

It's tempting to imagine that being the Capital of the North will transform our destiny in a way that being European Capital of Culture failed to do. But it's not about titles. It’s about a fundamental change in disposition, attitude and culture - and finding a way to overcome the inertia and mediocrity that emanates from our moribund and discredited civic governance.

Above all, it’s about remembering that once upon a time we were the first world city - our compass is omni-directional.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.