Recent features

It’s Time to Get Interesting

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to Manchester’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

Jon Egan

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to the city’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

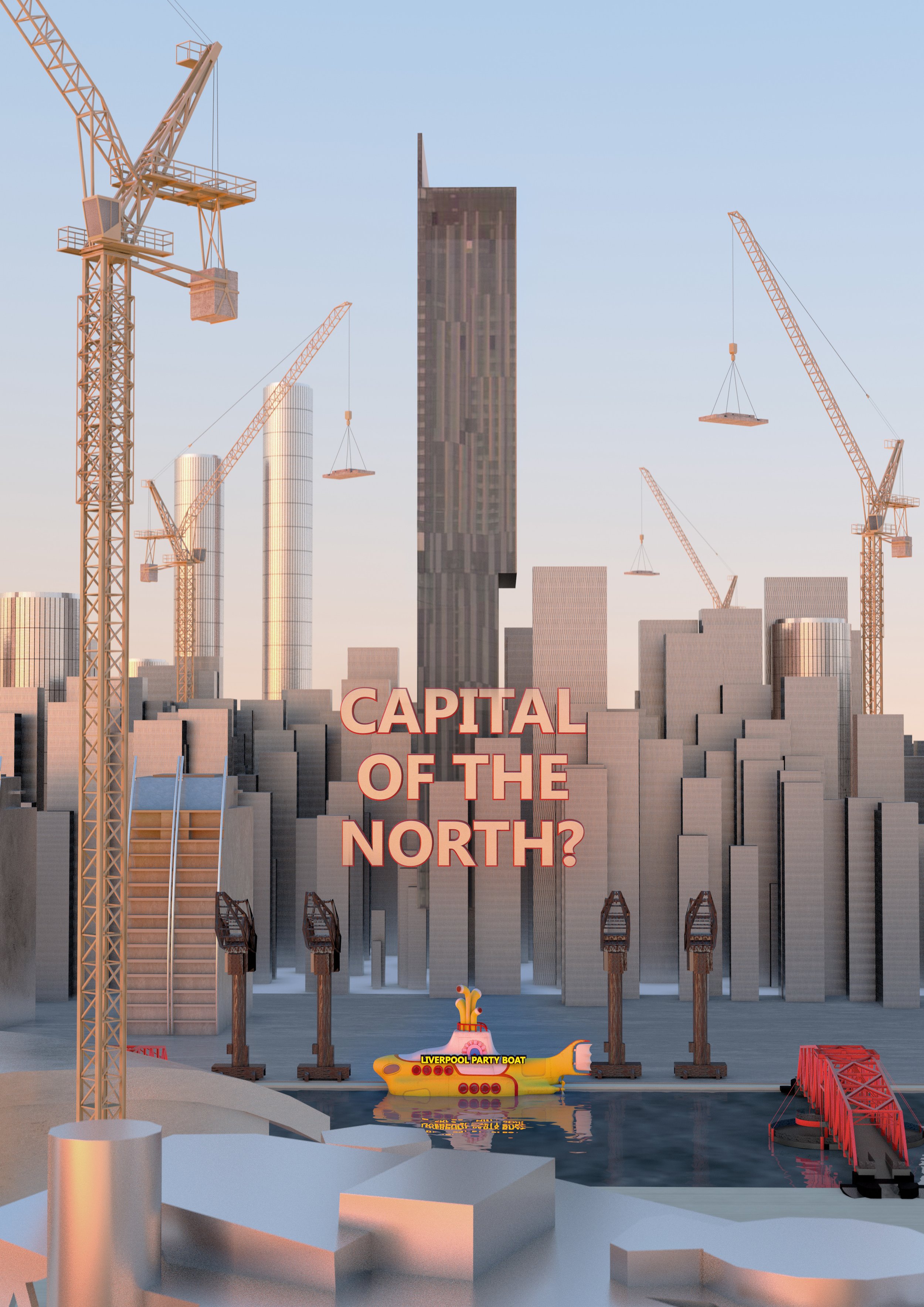

This long-forgotten televisual gem was brought to mind by a recent tweet from Liverpolitan which observed, sagely, that when Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of his own city’s expanding psychogeography. Under Burnham’s monarchic reign, Manchester has become the fulcrum of an aspiring northern nation. Its status as capital of the north is beyond dispute. Michael McDonough’s visionary prospectus for Liverpool’s Assembly District as a home for pan-northern regional government (beautiful and inspiring though it is) is destined to remain another sadly lamented ‘what if’. Liverpool’s own claims to northern dominance are a boat that has long since sailed and, like a great deal of our city’s historic wealth and prestige, are now securely moored at the other end of the Manchester Ship Canal.

Sorry if this sounds fatalistic and defeatist, but it’s an unavoidable truth. Manchester as regional capital has already happened and I can’t help feeling it’s actually entirely apposite. Liverpool is not, never has been and never will be the capital of the north for a very simple reason - we’re not in ‘the North.’

Let me explain. Some years ago when pitching for the brief that became the It’s Liverpool city branding campaign, my agency team and I presented an extract from a speech by then Tory Minister for Transport, Phillip Hammond. In it, he had been extolling the benefits of HS2, which he prophesied would unleash the potential of “our great northern cities.” To emphasise the point, and presumably to educate his London-centric media audience, he decided to identify these hazy and distant provincial relics that would soon benefit from an umbilical connection to London’s life-giving energy and dynamism. Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Sheffield, Bradford and even Newcastle (which wasn’t in any way connected to the proposed HS2 network) all made it on to his list. Our pitch focussed on Liverpool’s conspicuous absence from Hammond’s litany. We weren’t (as I opined in an earlier offering to this publication) ‘on the map’. We deduced that the speech was one more piece of definitive evidence that Liverpool wasn’t considered sufficiently great to merit a mention - nor important enough to be connected to a flagship piece of national infrastructure. But on reflection, there may have been another reason for the city’s omission. Perhaps we weren’t sufficiently northern! As if the inclusion of the offending syllables liv-er-pool would have somehow derailed this Lowryesque invocation of smoke stacks, cloth caps and matchstalk cats and dogs.

Of course, we are not talking about The North as a geographic region, or even an amalgam of richly diverse sub-regions, but as a mythic construct. However, as the French philosopher and founder of semiotics, Roland Barthes, would argue, myths are always distortions, albeit with powerful propensities to overcome and subvert reality. In this sense, northernness is not merely a point on the compass - It’s a complex abstraction, a constituent part of the English psyche and self-image that has strong connecting predicates and excluding characteristics. Geography alone is not enough to discern where The North begins and which enclaves and exclaves are to be considered intrinsic to its essential terroir. Isn’t Cheshire really a displaced Home County tragically detached from its kith and kin by some ancient geological trauma?

Thus when Government Ministers or London-based media commentators pronounce on "The North" they are all too often referencing a cloudy and amorphous abstraction defined not by lines on maps, but by indistinguishable accents, bleak moorlands and monochrome gloomy townscapes, nostalgically referred to as ‘great cities’. From this perspective, northerners are seen as honest, hardworking souls, who used to make things (when things were an important source of wealth and national prestige). Though stoical and resilient, they have a tendency, every generation or so, to get a bit bolshy, at which point it becomes necessary to reassure them of their place in our national life by relocating part of a prestigious institution to a randomly selected northern location, or by staging a second-tier sporting event such as the Commonwealth Games or perhaps even placating them with some vague commitment to ‘re-balancing’.

“When Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of Manchester’s expanding psychogeography.”

Manchester has been brilliantly adept at securing for itself more than its just share of these charitably dispensed national goodies. Largely that’s through a typically northern resourcefulness and pragmatism, but also because the city has ingeniously positioned itself as a shorthand synonym for the very idea of northernness.

Peter Saville CBE, the graphic designer who art-directed Factory Records and designed their most iconic album sleeves, also created the acclaimed Original Modern branding for Manchester in 2006. A predictably beautiful piece of graphic creation, it wove a vivid palette of cotton loom colours to represent a new Manchester, that was proud of its pioneering past but wanted to take that innovative DNA to recreate itself in the 21st century. It was wildly popular, but as an exercise in “re-branding” it didn’t succeed in challenging or reframing Manchester’s perceived identity. Instead, it merely set out to transmute it into something more contemporary and serviceable. Saville's project was to dig deeper into the Manchester’s vernacular version of mythic northernness, reflecting no doubt his immersion in Factory's overtly industrial aesthetic. It’s a restatement of core northern traits and a celebration of the city’s long-established narrative - the hub of the industrial north. Manchester’s sense of modernity was less about today and more an evocation of the 19th century, when it was considered the workshop of the world. Its originality was brilliantly expressed by the historian, Asa Briggs, who described it as the “Shock City of the age” - an urban phenomenon without peer or precedent in Europe and only matched by Chicago in North America. Cut forward to the early years of the Noughties. The opening of the ill-fated Urbis project – a new ‘Museum of the City’, conceived by Justin O’Connor and designed by Ian Simpson, was a bold assertion in shining glass and steel of Manchester’s boast to have been the world's first industrial city and the birthplace of the modern age. Despite the powerful statement of brand identity, it was a hopelessly unsuccessful attraction, closing after only two years in 2004. Its director candidly admitted that this monument to the city’s inventive and industrious spirit simply “didn’t work.”

Peter Saville’s Original Modern. Despite the fresh lick of paint, Manchester’s new branding campaign was curiously backward-looking.

In my article, Vanished. The city that disappeared from the map, I suggested that one radical option for Liverpool was to stop trying to compete with its eastern twin. Instead, I argued, we could become a new kind of urban entity - a city with two poles, which pooled our joint assets and balanced the two hemispheres of human consciousness to forge a global metropolis that could re-balance Britain without needing to turn to the patronising benevolence of London. Two hundred years after the building of the world’s first inter-city railway between Liverpool and Manchester, it seemed like a plausible and timely possibility to explore. I was wrong. Not because this idea is manifestly an anathema and heresy to every patriotic Liverpolitan (except me, it seems), but because Manchester is definitively and inexorably set on its own northern trajectory (even to the point where its most creative and happening urban district is aptly branded the Northern Quarter). Unlike Liverpool, Manchester's identity is embedded in its geography, and its literal place in the world. Its compass has only one co-ordinate and it isn’t west.

So where does that leave Liverpool? If we’re not part of The North, where in the world are we? Exiled and dislocated from our northern hinterland, we are a place apart; liminal and strangely detached from mundane geography. The recent media frenzy occasioned by the booing of the national anthem by Liverpool FC fans reignited a predictably shallow rehash of the “Scouse not English" debate, with the now familiar allusions to Margaret Thatcher’s alleged but never conclusively proven project to euthanize the city, compounded by the tragic injustice of Hillsborough. But these events were not the beginning of Liverpool's estrangement from its northern and English identity and its gradual drift to the edge of otherness. When in the second half of the 19th century our “accent exceedingly rare” began to emerge as something radically different to the dialects of neighbouring Lancashire, it was disparaged as “Liverpool Irish” - a vernacular that was deemed to be both alien and inherently seditious. As late as 1958, in Basil Dearden’s film Violent Playground - a British-take on the then topical theme of “juvenile delinquency” - the Liverpool street gang, led by a youthful David McCallum, are portrayed with accents that one reviewer of the DVD release, observed, “curiously owe more to the Liffey (Dublin's river) than the Mersey.” We were quite literally being depicted as foreigners in our own country.

Struggling to find a place within the recognised cartography of northernness, with a figure and stature too grandiose for the peripheral space allotted to us, where in the world can we find a comfortable and fruitful niche? The city that disappeared from the map has only one option - find a new map!

“Liverpool’s cultural programme is undoubtedly worthy, but how many people outside the city can name a single event, festival or programme that happens here?”

Let’s call it the map of interesting cities - places with an ingenuity and energy that is not defined by their geography, and whose confidence and chutzpah aren’t predicated on being the capital of anywhere or anything. Cities whose identity isn’t camouflaged or submerged into anything as nebulous as a region or a point on the compass. So let’s concentrate on being seriously interesting.

It’s a mantel that fits our self-image but we need more than the costume. It’s a project that demands a script and some serious acting. I genuinely think that Liverpool is an interesting city, it’s just that for too long we have marketed ourselves on the basis of our most boring and predictable traits.

We could take our cue from Austin, Texas, a city that markets itself with the slogan “Keep Austin Weird”. It based its civic renewal project on a determination “not to be Houston.” Austin’s promotion of independent business and cutting-edge creativity made it an early poster-child for Richard Florida’s boho-city thesis that diverse, tolerant and culturally cool metropolitan regions will exhibit higher levels of economic development. But Austin’s claim to be an interesting city pre-dates the self-conscious cultivation of weirdness as a kitsch merchandising gimmick. Austin devised and delivered what is now one of the world’s most prestigious gatherings of music, film and interactive media creatives at the annual SXSW festival. It’s an object lesson on how to make space for a genuinely international and seriously ambitious cultural proposition and use it to re-position and redefine a city.

Have we really built on the exposure of 2008 to deliver an internationally recognised programme of cultural events? For all the self-congratulatory posturing, Liverpool’s cultural programme is undoubtedly worthy, definitely diverse but how many people outside the city can name a single event, festival or programme that happens here? For all the energy and inventiveness invested in our pell mell of festive gatherings, we somehow manage to deliver a cultural calendar that is considerably less than the sum of its manifold parts. Places that use cultural events as the pivot for their positioning strategy generally do so by delivering one event or festival of genuine international scale and quality, as Edinburgh, Venice, Austin, San Remo, Cannes and Hay on Wye amongst others will testify. Similarly, “cultural cities” or UNESCO cities of music will normally look to validate that title with a programme that is commensurate with their claim or status.

I’m not going to predict or prescribe the event or theme that Liverpool needs to devise because there are bigger and better informed brains than mine who will be needed for that task. However, I do believe this city can build and sustain an international profile compatible with its brand and reputation by aiming higher and deploying its resources accordingly. For Austin, SWSX was not a travelling circus; it was an integral part of the city’s emergence from the shadows of Houston and Dallas to find its own profile and authentic magnetism. (For more information on Austin’s struggle to maintain its cultural identity try Weird City by Joshua Long).

Being interesting is a vocation. It demands creativity as well as rigorous discipline and hard work. It inevitably requires a style and quality of leadership that is absent from our dismal and discredited local politics. It’s ironic that the one aspect of our civic life that is without question unique and interesting, is so for all the wrong reasons. Liverpool's politics never fails to entertain, shock, frustrate and confound - if only it could achieve and deliver. In the 19th century, Liverpool not only spearheaded ground-breaking projects in rail, building technology and maritime engineering, we were also a wellspring for innovations in public policy and governance. Through pioneering initiatives like the introduction of the district nursing service and public washhouses, and the appointment of the world's first medical officer of public health, Liverpool's civic leaders responded to unprecedented challenges with entirely original structures and solutions. At a time when so many of the established prescriptions and paradigms are breaking down, we need to be plugged into the people and places that are responding creatively to challenges like climate change, technology & the future of work, life-long learning, democratic engagement or the next global pandemic.

Being interesting has to be a behavioural norm that finds expression across every sector and constituency. Are our politics interesting or innovative? Is our media intelligent and stimulating? Are we nurturing our most inventive businesses? Are we doing anything original or brave to address our challenges in education, housing or transport? How do we hope to stem the migration of talent, potential and ingenuity as too many of our best and brightest conclude that this city simply doesn't offer them a future? How do we emulate cities like Austin and become a magnet for innovators and entrepreneurs rather than a departure lounge?

Being interesting is fundamentally about being interested and connected to the wider world! It’s about being aware of what’s happening outside the insular and constricting straight-jacket of scouse exceptionalism or parochial northernness. It’s being open to outside influences and ideas and forging connections and relationships with kindred cities. Maybe we could become the convenor of the interesting city network - a global family of midsize cities free from the gravitational drag of conformity and contingent geography? Cities like Portland, Rotterdam, Hamburg, Auckland and Vancouver whose commitments to liveability and sustainability has sparked inventiveness in transport, urban planning, smart technology and the cultural industries.

If there is a common trait or attitude that connects these cities it is that they are porous, with a capacity and willingness to absorb ideas, influences and people from outside and beyond. Their thinking and ambition is not stunted by a perspective that is either provincial or parochial. They have a place in the world defined more by attitude and outlook than their position on the map. More often than not, they are ports and portals for cultural and human exchange. Auckland and Vancouver have flourished as a direct consequence of immigration, welcoming industrious and ambitious migrants from South Asia and East Asia. Despite our boast to be the World in One City, Liverpool is one of the least demographically diverse cities in the UK. Having at last stemmed our population decline, we are still growing at a discernibly slower rate than comparable cities like Leeds and Manchester. So let's grow our population by becoming an overtly immigrant friendly city, and proactively targeting one potential migrant population with whom we already have an historic and cultural affinity. Doesn't it make sense for the home of Europe's oldest Chinatown to be promoting itself as a welcoming haven for Hong Kong residents fearful of mainland China's increasingly despotic designs on the former colony? "Hungry outsiders wanting to be insiders" was a phrase coined by West Berlin in the 1980s as a strategy to reverse demographic and economic stagnation. It's an approach that a city built for twice its current population could usefully emulate.

Our new narrative can be built on familiar and cherished aspects of (or at least claims about) Liverpool's core identity - open, welcoming and global. But it's time to live them rather than simply intoning them as glib marketing slogans and nostalgic musings. Brands are about behaviour; their truth and utility is measured by what you do, not by what you say, so let's be consistently and ambitiously global not provincial.

In the same way that we need to rethink and curate our cultural programme to be genuinely international in terms of reach and quality, we should be enlisting global talent and expertise to help us rethink and reshape our city. Rather than flogging off prime sites like Liverpool Waters and the Festival Garden to whichever developer or volume house builder is offering the biggest buck, let's hold an international design competition to deliver the most innovative and sustainable new waterfront communities. Twenty years ago, Liverpool Vision was able to excite architects of the calibre of Richard Rogers, Rem Koolhaas, Will Alsop and Norman Foster in opportunities at Mann Island and King's Waterfront. It's a tragic shame that none of their inspired visions came to fruition, but let's resolve to try harder and be clear and consistent about who we are and how we intend to renew and reposition our city.

It's tempting to imagine that being the Capital of the North will transform our destiny in a way that being European Capital of Culture failed to do. But it's not about titles. It’s about a fundamental change in disposition, attitude and culture - and finding a way to overcome the inertia and mediocrity that emanates from our moribund and discredited civic governance.

Above all, it’s about remembering that once upon a time we were the first world city - our compass is omni-directional.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Vanished. The city that disappeared from the map

When I was a young child my parents bought me a truly wondrous gift ‐ an illuminated globe of the world. It was a magical object with the power to inspire and enrapture, but it also taught me two important, but hitherto unknown, facts about the world. The first was that my country, Britain, was very small. So small in fact that it was only possible to fit the names of two cities onto this tiny morsel of irradiated pinkness.

Jon Egan

When I was a young child my parents bought me a truly wondrous gift ‐ an illuminated globe of the world. It was a magical object with the power to inspire and enrapture, but it also taught me two important, but hitherto unknown, facts about the world.

The first was that my country, Britain, was very small. So small in fact that it was only possible to fit the names of two cities onto this tiny morsel of irradiated pinkness. The second lesson, that followed ineluctably from the first, was that my city clearly was important. As far as the world was concerned Britain could be adequately represented by only two places – London, its capital, and Liverpool, its global gateway. We were on the map, or at least we were then.

A few years ago, when passing through the John Lewis department store, I stopped to browse at a selection of highly impressive (but sadly not illuminated) globes. Britain remained within its familiar miniscule dimensions, but the cartographers had skilfully managed to inscribe on its terrain the names of not two, but five significant British cities – London, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and Glasgow. It merely confirmed what I had long suspected ‐ we were no longer important.

There is of course a serious point to this parable, and it is that we are not simply absent from physical maps, but also from the conceptual and metaphorical maps that shape policy and influence important decision‐making. Despite the incessant hype to the contrary, data from the Centre For Cities suggests we are making little progress in closing the performance gap with competing and emerging economic centres.

A well‐placed insider described Liverpool as “the city that has forgotten how to conjugate in the future tense.”

We have become peripheral ‐ largely outside the thought processes and priorities of political decision‐makers, investors, media commentators and influencers. Addressing and reversing this process – or putting Liverpool ‘back on the map’ ‐ has been, or certainly should have been, a guiding principle for our political and civic leaders over the last four decades. With a City Council mired in crisis and multiple criminal investigations, and the most recent State of The City Region (2015) report presenting a picture of chronic levels of ill‐health, worklessness and deprivation, it’s clear we still have a very long way to go.

For anyone wondering if the economic picture has improved since that last report was published, check out the tale of woe in the new Shaping Futures report, The Demographics and Educational Disadvantage in the Liverpool City Region (2021).

My own involvement with efforts to reposition and rehabilitate Liverpool’s external image has been deeply frustrating and depressingly circular. When in 2002 Liverpool was bidding to become European Capital of Culture, bid supremo, Bob Scott, suffered a heart attack in the closing stages of the process. City Council CEO, Sir David Henshaw took control of the bid, and invited myself as director of the agency that had devised the bid’s World in One City branding, and the Lib Dem’s political strategist, Bill le Breton, to review the campaign and communication messaging. This was an interesting and instructive exercise. Talking to people very close to the then Culture Minister, Tessa Jowell, and contacts equally close to the leading members of the judging panel, the feedback on Liverpool’s campaign pitch was not entirely encouraging. One of the most memorable comments from a very well‐placed insider described Liverpool as “the city that has forgotten how to conjugate in the future tense.” In a competitive process that was supposedly about regeneration and the role of culture in stimulating economic transformation, Liverpool had, until that point, focused almost entirely on showcasing its “great cultural heritage” and waxing nostalgically about its past glories as the Second City of Empire.

A radical rethink was needed, and fast if the city was to be ready in time for the judges’ second visit. We’d need a whole new bid narrative, rigorously disciplined messaging and a tightly scripted programme to change hearts and minds. The new story would be about the future ‐ a city applying its creative energies to embrace cutting‐edge culture, commerce and technology – and it worked. The only problem was that having won, we quickly abandoned the brave, new language and future‐focused vision. 2008 became, as Phil Redmond, Capital of Culture’s, last‐minute appointee as Creative Director, once testified, the proverbial “Big Scouse wedding” with Uncle Ringo on the karaoke.

Consigned to the second tier of UK cities, Liverpool had somehow become pigeon‐holed as economically and maybe even culturally irrelevant.

Fast forward to 2010 and the festival’s former marketing supremo, Kris Donaldson, arrives back in Liverpool to take up a new position as the city’s Destination Manager, only to discover that the promise of Capital of Culture as a platform to radically re‐position Liverpool had largely been squandered. Research commissioned by economic regeneration company, Liverpool Vision had suggested the city was perceived as quirky and entertaining, but news of its “regeneration miracle” was still a dimly perceived rumour amongst the nation’s influencers and decision‐makers. Without any significant expectation of success, I joined forces with journalist, political campaigner and former BBC Radio Merseyside broadcaster, Liam Fogarty and two local creatives (Jon Barraclough and Chris Blackhurst) to pitch for the city re‐branding brief that emerged from Kris’s sobering discovery. Our proposal was less of a pitch and more an indulgent exercise in provocation. Having initially been sifted out of the process by a dutiful underling at Liverpool Vision, Kris reinstated us onto the shortlist for interview. Our presentation began with a miscellany of quotes from ministerial speeches, broadsheet Op‐Eds and the authoritative musings of a polyglot of professional commentators. They were all opining on the need for economic re‐balancing and the incipient promise of that great new hope, the Northern Powerhouse. But amongst their mountain of words, one city was consistently and depressingly absent, and it was of course, Liverpool.

Permanently consigned to the second tier of UK cities, Liverpool had somehow become pigeon‐holed as economically and maybe even culturally irrelevant. The bold promise of 2008 had been replaced by fatalistic resignation, punctuated by occasional blasts of delusional bombast and mawkish nostalgia. As a result, Liverpool ceased to be discussed when the adults were in the room.

Winning the brief, with an ominous feeling of déjà vu and an almost Sisyphean sense of futility, we set out to equip the city once again with a future tense vocabulary and a story that would surprise and challenge the preconceptions of those we most needed to convince and convert. But like an aging soap star struggling with new scripts and plot lines, the city inevitably lapsed into its well‐worn phrases and crowd‐pleasing clichés. The It’s Liverpool campaign became less of a device to “package surprises” and orientate future ambition, but more an excuse to recycle familiar messages and tell the world what they already knew.

Fast forward another seven years to 2017 and I am sitting in the campaign HQ of the man bidding to become the first Liverpool City Region Mayor, the Labour MP for Walton, Steve Rotheram. We are discussing how to frame a transformational narrative for his soon to be launched election campaign. I find myself agreeing with him that devolution is the last chance saloon for a city (or City Region) being left behind by its competitors and too often ignored by those whose judgments and decisions shape its future. I think we may even have used the phrase “putting Liverpool back on the map” as shorthand for a project to reassert the city’s status as a Premier League player (forgive the clumsy football cliché) ensuring it once again became an integral component in the national economic narrative. I was increasingly hopeful that Steve’s refreshingly insightful analysis of the city’s deficiencies could be the prequal to a visionary devolution project. Four years on, and the consensus is that our Metro Mayor has yet to reset Liverpool’s trajectory or restore our status as an important economic or creative asset for the UK. If devolution was the last chance saloon, then the barman, with one eye on the clock, appears to be reaching ominously for the towels.

Four years on, and the consensus is that our Metro Mayor has yet to reset Liverpool’s trajectory or restore our status as an important economic or creative asset for the UK.

The initial stimulus for this article was the then imminent launch of Rotheram’s re‐election campaign in March 2020, before, of course, normality was put on hold by Covid and what we imagined were urgent political challenges dissolved into irrelevancy in the face of a global human tragedy. That earlier, never published version of this article, drafted in the format of an open letter to the Metro Mayor‐elect, was triggered by a series of events that acted as timely reminders of our reduced circumstances. Former Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne had used his resignation as Chair of the Northern Powerhouse Partnership to restate his vision of a rebalanced Britain where the “great cities of the north” (predictably we weren’t name‐checked) counterbalanced the wealth and prestige of London. But the tipping point for me, however, came on a day when Rotheram launched the latest phase of the Mersey Tidal Energy study, part of his big plan to recast the Liverpool City Region as an exemplar for sustainability and innovation. He might as well as not have bothered for all the attention it got. Instead, on that same day, a Simon Jenkins’ Guardian Op‐Ed calling for economic rebalancing, once again seemed to have been drafted with a map of Northern England where Liverpool was inexplicably absent. Twelve years after Capital of Culture and four years after devolution, the sad fact is that we are still not on the map.

The constructive, and at the time topical, section of the article was a positively motivated attempt to offer some suggestions for Rotheram’s critically important second term. Not that I thought I was especially qualified to provide such advice, but more to help stimulate a bigger, smarter and more diverse political conversation – in fact, the kind of energised democracy that devolution was designed to foster.

In a strange way Covid has given us more time, and an even more urgent imperative to take stock of where our City Region is heading. We need to be more radical, more imaginative and more willing to challenge the myths and shibboleths that have constrained thinking, blighted ambition and stunted potential.

So, in that spirit, here are five ideas about how we might help to remake and re‐position our city.

1. Appoint smart people – preferably from places more successful than Liverpool

Scouse exceptionalism and insularity are tragically compounded by a debilitating public sector culture. As the employer of last resort, our public institutions have evolved a defensive protectionist mindset that all too often fosters inertia and promotes mediocrity. I’m not necessarily advocating a Dominic Cummings‐style cull of staff and an invitation to assorted geeks, weirdos and misfits to replace them, but for devolution to make a difference it needs to be delivered by different people with higher levels of ambition, achievement and creativity. The kind of people capable of imagining possibilities beyond the recently launched hotchpotch of reheated pet projects and lame platitudes which masquerade as the city’s “transformational vision” for a post‐Covid future. What we need more than anything are people with a track record of delivery in a city or City Region that is palpably more successful than Liverpool. To extend the football analogy, we need a Klopp rather than a Hodgson; an Ancelotti or Benitez, not a Big Sam.

Rather than a being a dynamic galvanising body with a transformational agenda, our post‐devolution governance has somehow coalesced into an unhappy amalgam of Merseytravel and the Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP) – a stifling bureaucracy with a highly developed aversion to any form of risk or innovation. For the next term to be successful, our Metro Mayor needs to transform the calibre, capacity and orientation of the Combined Authority. It remains to be seen whether the new Head of Paid Service can create a different dynamic and organisational culture or can inculcate the expansive perspective that has thus far been absent from our devolution project.

2. Have a story that makes sense, and then stick to it

Liverpool’s tragedy is that it is famous but no longer important. It means people already have an idea about who we are, what we’re good at and what we’re not so good at – like having an economy. The Combined Authority issued a brief to create a new City Region narrative, but the process seemed to be firmly in the hands of people who were too deeply immersed in the old dispensation, and too easily seduced by trite PR‐speak and marketing gobbledygook. So, here’s a radical suggestion – and one in the spirit of recommendation 1 – let’s appoint a world‐class creative with an international reputation to help us frame and articulate what this City Region is about. There are extraordinary flowerings of innovation and excellence here, but they currently look more like an advent calendar than a big picture. Rather than designing another procurement process and issuing yet another brief, why don’t we appoint somebody of the calibre of Bruce Mau, the Canadian branding and design genius? Let’s get a fresh set of eyes to re‐imagine the planet’s first “World City” and the place that globalised popular culture. Unless we can answer the existential question – what is Liverpool for? – we cannot hope to persuade people that we are still relevant today.

3. Get out there and spread the message

OK, I understand the electoral context and the reason why it was attractive for Steve Rotheram to launch the Tidal Energy study ‐ and a raft of more recent policy announcements ‐ in his own back yard, but guess what? No‐one east of Newton‐le‐Willows is taking any notice. The world is not watching or listening to Liverpool, so we need to get out there and tell them. That means doing the big announcements in London or wherever they’ll get noticed. It means having a Metro Mayor who is prepared and confident to do the awkward, challenging and high‐risk national media gigs. It means being willing to get on planes and fly to the four corners of the earth to spread the Liverpool (City Region) message. The great thing about not being weighed down with a plethora of statutory and service delivery responsibilities, is that a Metro Mayor can be our foreign minister, our ambassador – the kind of advocate and propagandist that this place has lacked and still so badly needs.

4. Find the causes and campaigns that make the story sticky and believable

As Boris Johnson so ruthlessly demonstrated in the Brexit and General Election campaigns, the world, the media ‐ and especially social media ‐ abhor complexity. Messages need to be sharp, self‐explanatory and sticky. They need to reveal and illuminate the bigger picture, and have the power to vanquish the myths, clichés and stereotypes that continue to blight perceptions of the City Region. We need to be able to definitively answer some key questions. What are the three most important ideas that can be the foundation of a new economic identity that gives our City Region a competitive edge and compelling new story? How do they connect? Who will they effect and why is it absolutely vital and non‐negotiable that we deliver on them? Whatever these ideas prove to be, underpinning them is a very simple ambition; to make Liverpool not just relevant, but also important – somewhere that is vital to the vision of a rebalanced, prosperous and successful UK.

5. Look for short cuts – if necessary, borrow someone else’s reputation and influence

It’s possibly the quickest win and the hardest pill to swallow, but we do have one big asset on our doorstep that could and should be mobilised to our advantage. George Osborne once observed that Manchester and Leeds city centres are closer to each other than the two ends of London’s Central tube line. Perhaps, from the distant vantage point of the Evening Standard editor’s office, he is unable to see the inconveniently positioned mountains or the fact that Liverpool and Manchester are even closer together! We even share two centuries of economic interdependence, and between us possess all of the attributes that sociologist, Saskia Sassen identifies as the defining characteristics of a global city. Abandoning football terrace rivalry to position Liverpool City Region closer to its burgeoning neighbour is both logical and necessary. An integrated transport authority, a shared policy unit and a merged LEP are all ways in which Liverpool City Region could begin to reposition itself within an expanded urban economy with the scale and asset base to counter‐balance London. Let’s not be constrained by redundant mindsets or arbitrary administrative boundaries. Liverpool – and Birkenhead – more than anywhere else can claim to have invented the template for modern civic governance in Britain, so why not pioneer new and liberating models designed to deliver the levelling‐up economic agenda, that will otherwise remain pious rhetoric?

Of course, these suggestions were offered in the confident expectation that the Metro Mayoral election was a mere procedural formality. Not even the implosion of Mayor Joe Anderson’s city mayoralty, the Caller Report and the national party investigation into Liverpool Labour were able to dent Rotheram’s majority. Labour’s almost Belarussian control of the City Region, and the fatalistic impotence of a fractured opposition, leaves us with a hollowed‐out politics where, notwithstanding the heroic efforts of Independent candidate Stephen Yip, the impetus for an inclusive civic discourse is blunted by establishment complacency and partisan insularity. A competitive electoral democracy, intelligent media scrutiny and strong independent civic voices (rather than meek subservience to the local state) are the prerequisites for energised politics and the possibility of a visionary civic project. So maybe the big question isn’t simply about what Steve Rotheram and Joanne Anderson need to do next, but how do we make space for genuinely transformational alternatives that might help Liverpool regain its former economic prestige and put us back on the map.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

Don’t knock it till you’ve tried it!

Following the announcement that UNESCO had stripped Liverpool of its World Heritage Status, there have been a myriad of social media posts and articles about what this means (or doesn’t mean) for the City. Some expressed mild disappointment and some adopted a more ‘we’ll be fine without it’ approach.

Lynn Haime

Following the announcement in July that UNESCO have stripped Liverpool of its World Heritage Status, there have been a myriad of social media posts and articles about what this means (or doesn’t mean) for the City. Some expressed mild disappointment and some adopted a more ‘we’ll be fine without it’ approach.

It did, however, make me pause to consider my city - its charms, shortcomings, history and future and ultimately conclude that, once again, the external perception of Liverpool will have unfairly taken a knock.

Having lived, studied or worked in the South, Birmingham and Manchester over the past 20 or so years it reminded me that, unlike any other city, we regularly have to defend our position and correct misinformed views of Liverpool. I have penned this article for colleagues, friends and family who have either never visited the city, or have not revisited it for years. Some of the views of those who are unfamiliar with Liverpool are exacerbated by the consistent and inaccurate stereotypes from the ill-informed. Hangovers from days of rioting and overtly vocal politicians dominating our screens in the 80s, to the more light hearted, tracksuit-donning, curly wig-wearing characters portrayed on television – admittedly very funny at the time, but over 30 years later, they are just an irritating perpetuation of an image which couldn’t be further from today’s Liverpool.

In 2008, Liverpool was European Capital of Culture which catapulted the city to another, much more positive level of exposure. The significant impact of that is still felt today - on cultural initiatives, regeneration, visitor numbers and economic growth. Clearly all is not yet perfect and we sighed in collective exasperation at the recent exposure of questionable practices from certain high-level public servants. It was a setback caused by a very small minority which unfortunately reinforced some of those outdated stereotypes. The majority of us work hard to promote the city, encourage investment and enhance the already exciting opportunities which exist. But this was a disappointing blow. However, it is being addressed admirably by Tony Reeves, the current Chief Executive of Liverpool City Council. He has helped to expose the previous, less scrupulous practices and promote a more transparent and trustworthy platform on which to build.

…we regularly have to defend our position and correct misinformed views of Liverpool.

One of the key concerns cited by UNESCO was the development of Everton’s new 52,000-capacity stadium on the waterfront. Its official address is Bramley-Moore Dock, which Wikipedia describes as ‘a semi-derelict dock on the River Mersey’. It’s a stone’s throw away from Bootle which remains one of the most deprived areas in the UK. Everton FC have jumped through planning and heritage hoops and will be investing over £500m in developing their new stadium, which will deliver an estimated £1.3bn boost to the local economy, create more than 15,000 jobs and attract 1.4m new visitors to the city.

The project budget includes £55m for ‘preserving, restoring and celebrating the heritage assets’ and is located in an unloved part of town and what was the ‘buffer zone’ of the World Heritage designation. The main UNESCO site was focused elsewhere, around the majestic Three Graces (The Grade 1 listed Royal Liver Building, Port of Liverpool and Cunard buildings). Regardless of UNESCOs decision, all three remain standing proud and unaffected, overlooking the Mersey and adjacent to the magnificent Royal Albert Dock.

The area connecting Everton’s new stadium to that world famous waterfront is largely under the ownership of Peel Land & Property and their £5.5bn Liverpool Waters project. Should that scheme ever go-ahead, it will bring further regeneration and investment to entirely new communities along the waterfront, providing a vital link between the city centre, the northern fringe and the new stadium.

Everton FC have jumped through planning and heritage hoops and will be investing over £500m in developing their new stadium…

Also in the mix is the Stanley Dock and Ten Streets Regeneration area including the Titanic Hotel, one of Liverpool’s most popular stay-overs and the Grade II Listed Tobacco Warehouse, Europe’s largest brick building and soon to be home to 538 apartments and 100,000 sq ft of new commercial space. My own view, echoing many others, is that whilst UNESCO endorsement was nice to have, this investment and regeneration will be far more wide-reaching, directly beneficial for the city and a real catalyst for future growth. I would encourage anyone who hasn’t visited Liverpool to come and see it for themselves. I’ve found over the years that those with negative views of the city are those least familiar with it. It seems this can also be said of UNESCO who made their decision without setting foot here in over 10 years.

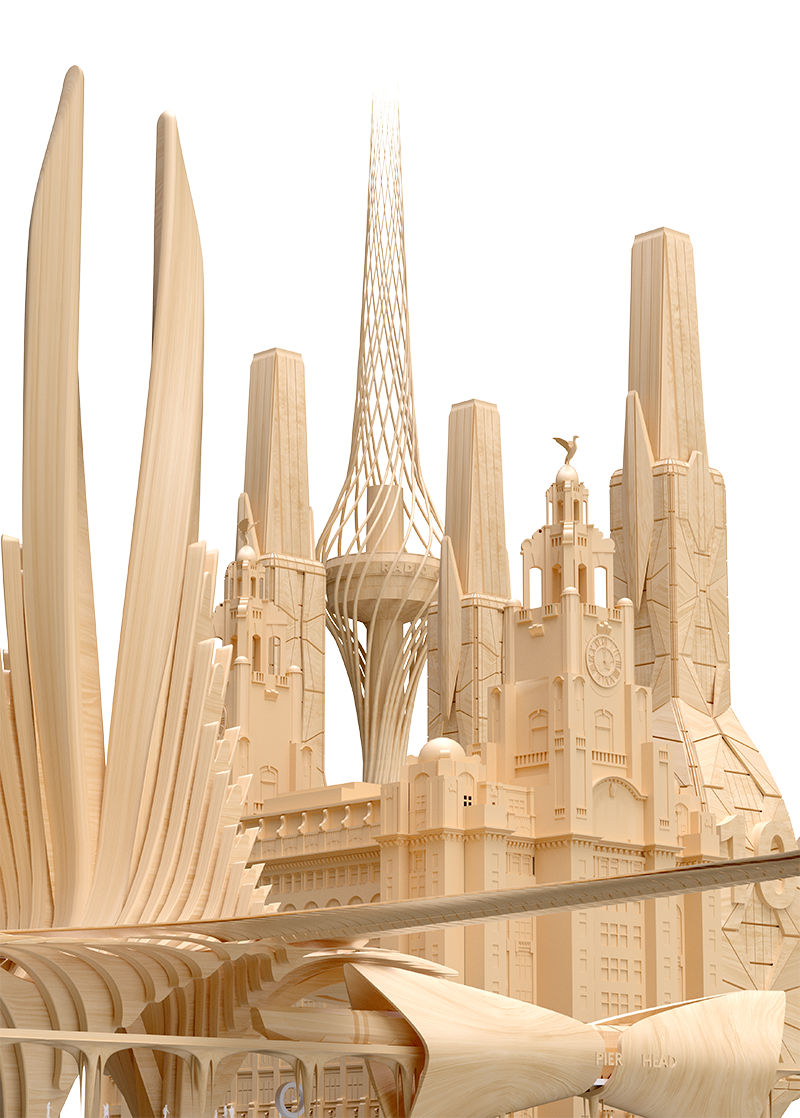

A future Liverpool skyline after UNESCO?

The overwhelming majority of comments on the removal of World Heritage Status expanded on the many virtues of Liverpool, far more eloquently than I could. The culture, history, architecture, the magnificent cathedrals, the waterfront, two world-class football clubs, successful universities, its extensive talent pool, world leading science institutions, incredible nightlife, and the amazing people. Of course, no commentary on Liverpool would be complete without mention of the four sons of the city. The most successful group of all time and famous the world over, The Beatles still generate around £20m per year for Liverpool through tourism. The removal of our World Heritage badge will not deter the streams of overseas visitors hopping on to the Magical Mystery bus to Penny Lane, Strawberry Fields, The Cavern, and the birthplaces of John and Paul. As one of my southern colleagues mentioned, Abbey Road… I pointed out that this was in London and rested my case.

Lynn Haime is a Partner at commercial property consultancy, Matthews and Goodman. She heads up their Liverpool office.