Recent features

Ye Wha? Opera on the Mersey and other Mad Visions

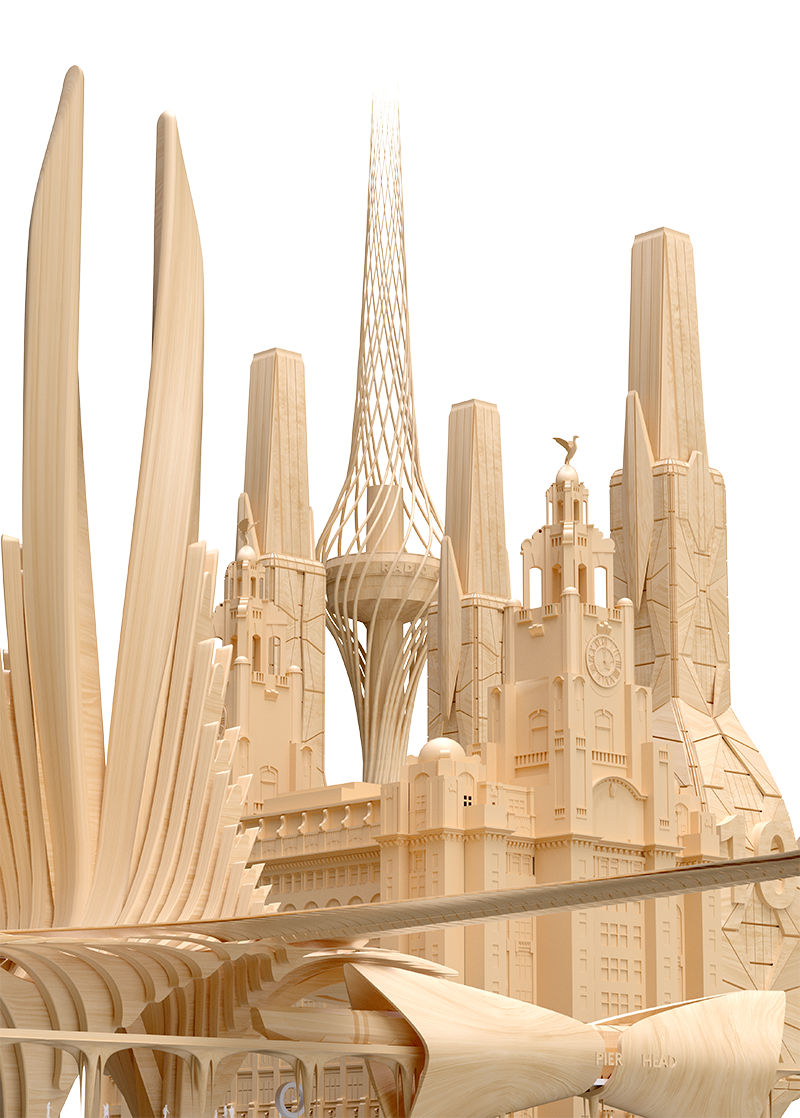

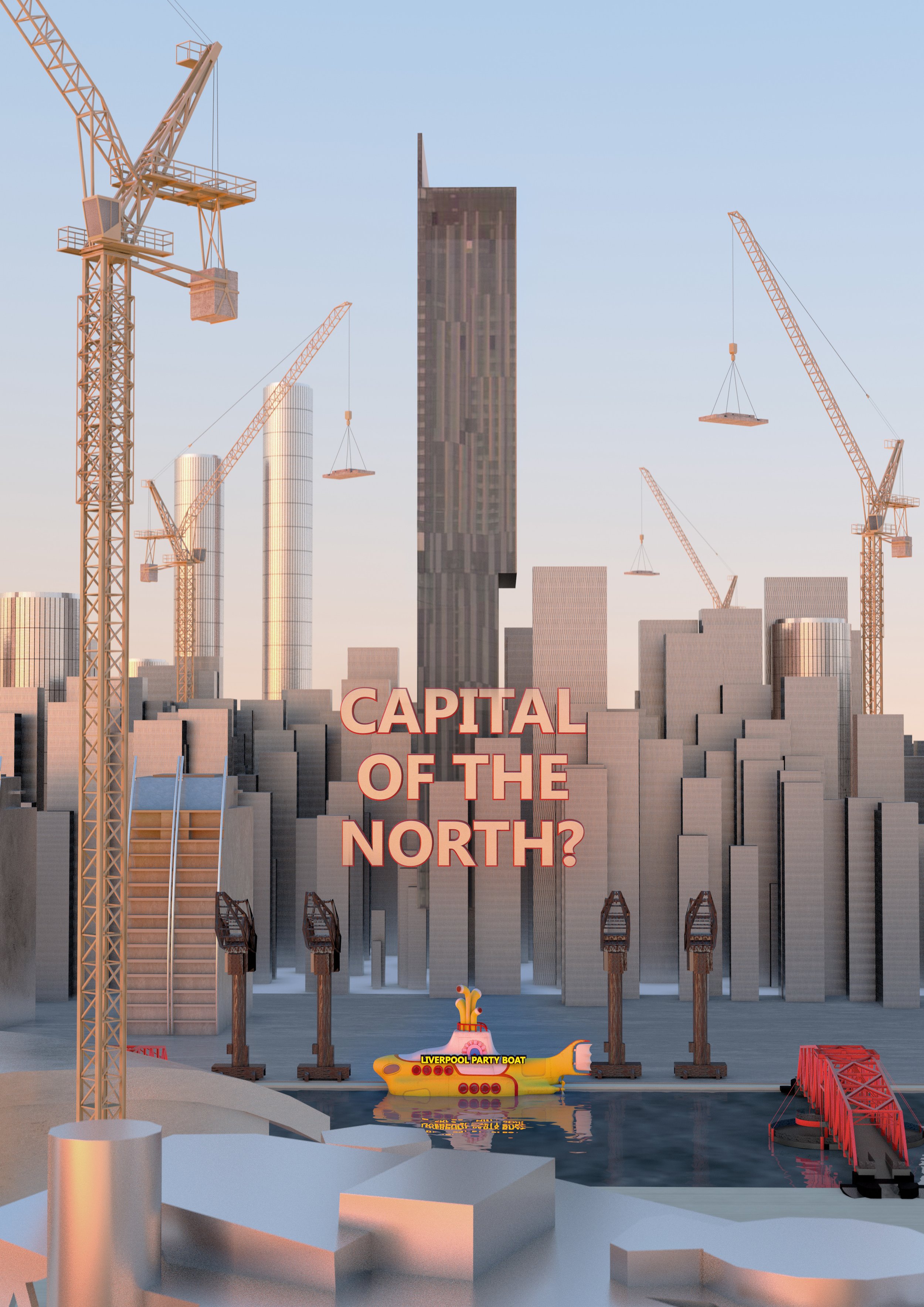

For over ten years, 3D animator Michael McDonough, has been dreaming up new ways to re-imagine Liverpool’s urban landscape – designing outlandish opera houses, cathedral-like train stations, gothic bridges, and new visions for the docks. None of them have been built or are ever likely to be. But why does he bother? In this showcase of his work, Liverpolitan Editor, Paul Bryan explores Michael’s fascinating dreamscapes of the imagination.

Paul Bryan

“The way I come at things is to make no small plans. The city has had too much of that, too much dross, too much crap, too much small time thinking.”

So says Michael McDonough, Co-Founder here at Liverpolitan, and a man who has developed a bit of a reputation for his outspoken criticism of Liverpool’s (lack of) development scene. And in fairness, it’s a view that I, as the magazine’s Editor, often share.

One of the things that makes Michael interesting to me (other than the fact he’s had to develop skin as thick as a rhinosaurus to bat off ‘the army of gobshites’ who take him on or even pose as him online) is the fact that despite a successful career as a 3D designer and animator which has taken him to the capital, he continues through his design work to try to make a positive contribution to his home city of Liverpool and the discussion about its future. He does this without fanfare or gratitude and in fact, often in the face of quite complacent criticism from ‘locals’. Often by people with far less talent or insight than himself. For over ten years now, entirely under his own steam, Michael has been dreaming up new ways to re-imagine Liverpool’s urban landscape – designing outlandish opera houses, cathedral-like train stations, gothic bridges, and new visions for the docks. None of them have been built or are ever likely to be. They are not fully formed architectural plans, more dreamscapes of the imagination and we’ve made a showcase of that work in this feature article.

But why does he bother? What’s the point? Aren’t they just castles in the air built before AI and Midjourney made fantastical images the prerogative of all? To believe so would be to miss what’s really going on. There’s a much harder edge lying beneath the glossy visuals. He’s making the case for ambition as an antidote to a city-wide loss of nerve.

“We should be thinking in the same way world cities do like London, Singapore and New York. All these places have big ambitions. We should be looking to emulate that,” says McDonough. Instead, he believes Liverpool increasingly seems resigned to a lower status and too often its mediocre plans reflect that. Small schemes are favoured over transformative ones and then heralded as being the way forward. Anything substantial or showy is typically treated with hostility and suspicion.

“I keep hearing that in Liverpool we’re different, that we have our own models of success, but it’s a language of defeatism, masked and airbrushed as some kind of urban superiority.” He rejects this idea totally. “Being different doesn’t mean you reject ambition, scale and big ideas. That doesn’t make you different, it just makes you stupid.”

‘There’s an obsession in Liverpool’s planning circles with ‘context’ – the idea that new developments must be submissive to the city’s crown jewels."

Michael’s designs are meant in sharp contrast to the veritable cottage industry of ‘place-making’ peddlers, much favoured in recent years by our city leaders, whose low aspiration output chimes with this defeatist mindset. Meanwhile, the same old local architectural practices win job after job, churning out budget off-the-shelf buildings that further erode what makes the city special. There’s an obsession in Liverpool’s planning circles with ‘context’ – the idea that new developments must be submissive to the city’s crown jewels. But that attitude just results in bad buildings and Michael’s designs deliberately shun such restrictions. Some of his designs will inspire, but also enrage.

“The irony,” says McDonough, “is that those buildings we love so much are there purely because of ambition, because of power and commerce. They didn’t just land there as gifts from God.”

The point of history is to learn from it, not to fetishize it. We do Liverpool’s history a disservice by feeble attempts at mimicry. The Liverpool of yesteryear was bolder and more global in its perspective and if we are to take something useful from the past, it should be that. What Michael is attempting to do with these designs is to remind the city that it’s capable of bigger ideas, capable of re-imagining itself, capable of statement architecture, and capable of challenging its city rivals.

“What pushes me to create these designs is a desire to make people see the city differently – and by that I mean primarily the people who live and work within it. Because if we can awaken that boldness of old, so much is possible in our future,” says Michael. That is the lens through which he’d like people to view his designs. Of course, design is subjective. What might be considered beautiful by one person, can be viewed as horrendous by another but he claims to welcome those reactions. “One of our motivations for founding Liverpolitan magazine, was to create a place where thoughts and ideas on the city’s built environment could be shared, discussed and visualised – to think beyond self-constrained limitations,” he concludes. And indeed that is part of our mission.

So buckle in. This is Michael’s contribution. We hope others will be inspired to contribute in the future. It’s a long read. You may need a cup of tea. But there are lots of pretty pictures and food for thought.

Enjoy.

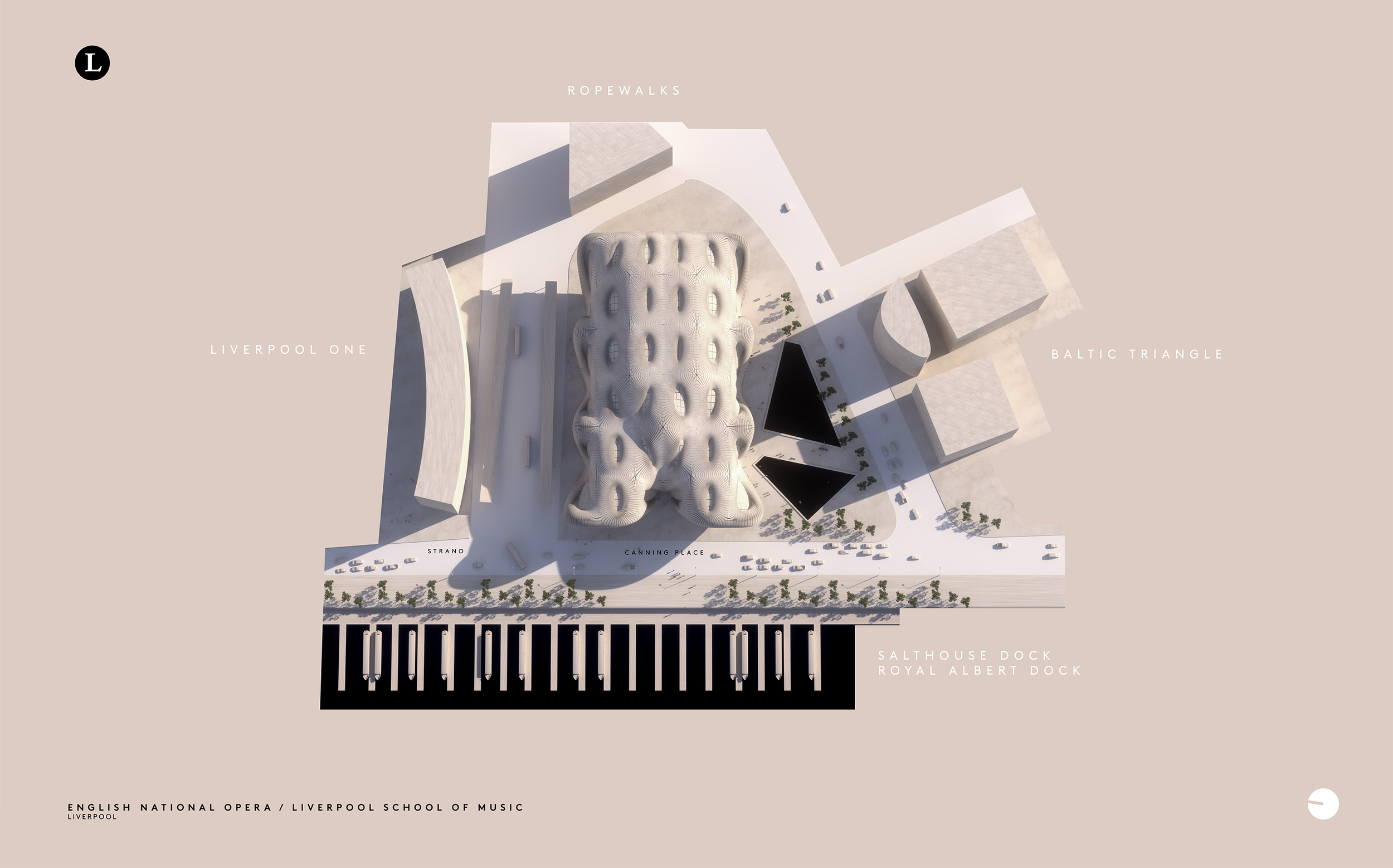

English National Opera, Liverpool

Post-Eurovision, Liverpool emerges with its reputation for hosting big events enhanced and attention inevitably turns to ‘what next?’ So how should the city attempt to capitalise on this positive exposure? Capitalise being the key word here – turning the benefits of a one-off event into something long-lasting, and preferably given a tangible physical form.

Step forward candidate 1: The English National Opera (ENO). This prestigious London-based institution has been told by its funders, Arts Council England, that if it wants the purse strings to remain untied, the institution needs to up-sticks and move to the regions, and rumour has it that Liverpool is very much on the short-list. Some will question why a city like Liverpool needs opera, but even if Tosca and Turandot are not your kind of thing, attracting such a high profile organisation will only add to Liverpool’s cultural offer and open up new job opportunities for young people who might otherwise fly the nest.

Dreaming up a new opera house on the banks of the Mersey, is something that dates back to the wild and unfunded dreams of former Mayor Joe Anderson. But this time, at least in theory, the prospect sounds a little more plausible. Not fully plausible mind – a recent article in The Post claimed the move might be more northern outpost than wholesale relocation, akin to Channel 4’s setup in Leeds. Still, it’s not completely out of the equation – especially if a new facility could combine uses with other functions – education, meeting space, performance arts. Back in 2021, the then-chancellor, Rishi Sunak allocated £2m for a feasibility study into some kind of new immersive music attraction. So despite initial talk of yet another Beatles-focused space, perhaps there’s scope for blending these projects onto one site to make the whole more achievable.

‘The point of history is to learn from it, not to fetishize it. We do Liverpool’s history a disservice by feeble attempts at mimicry.’

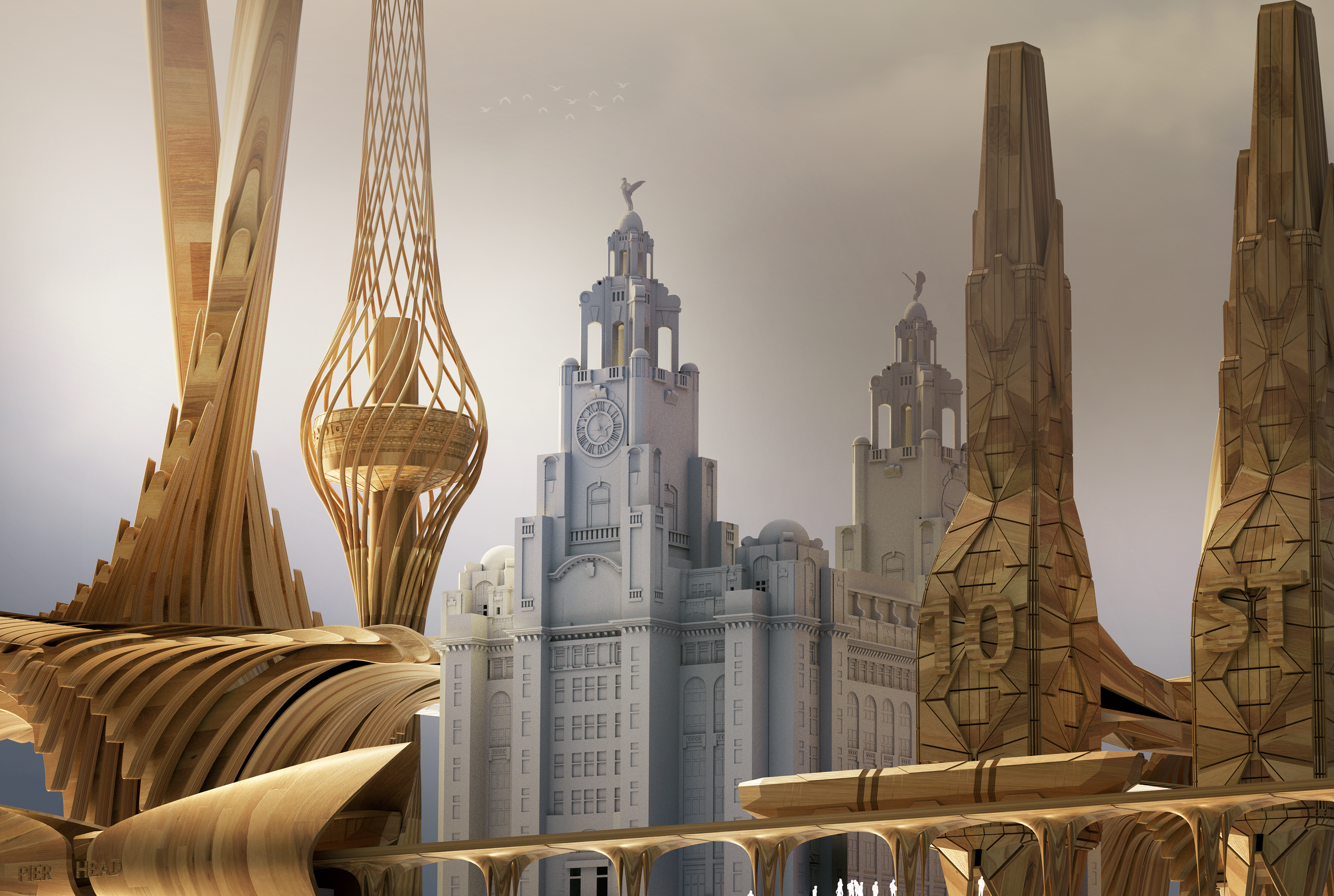

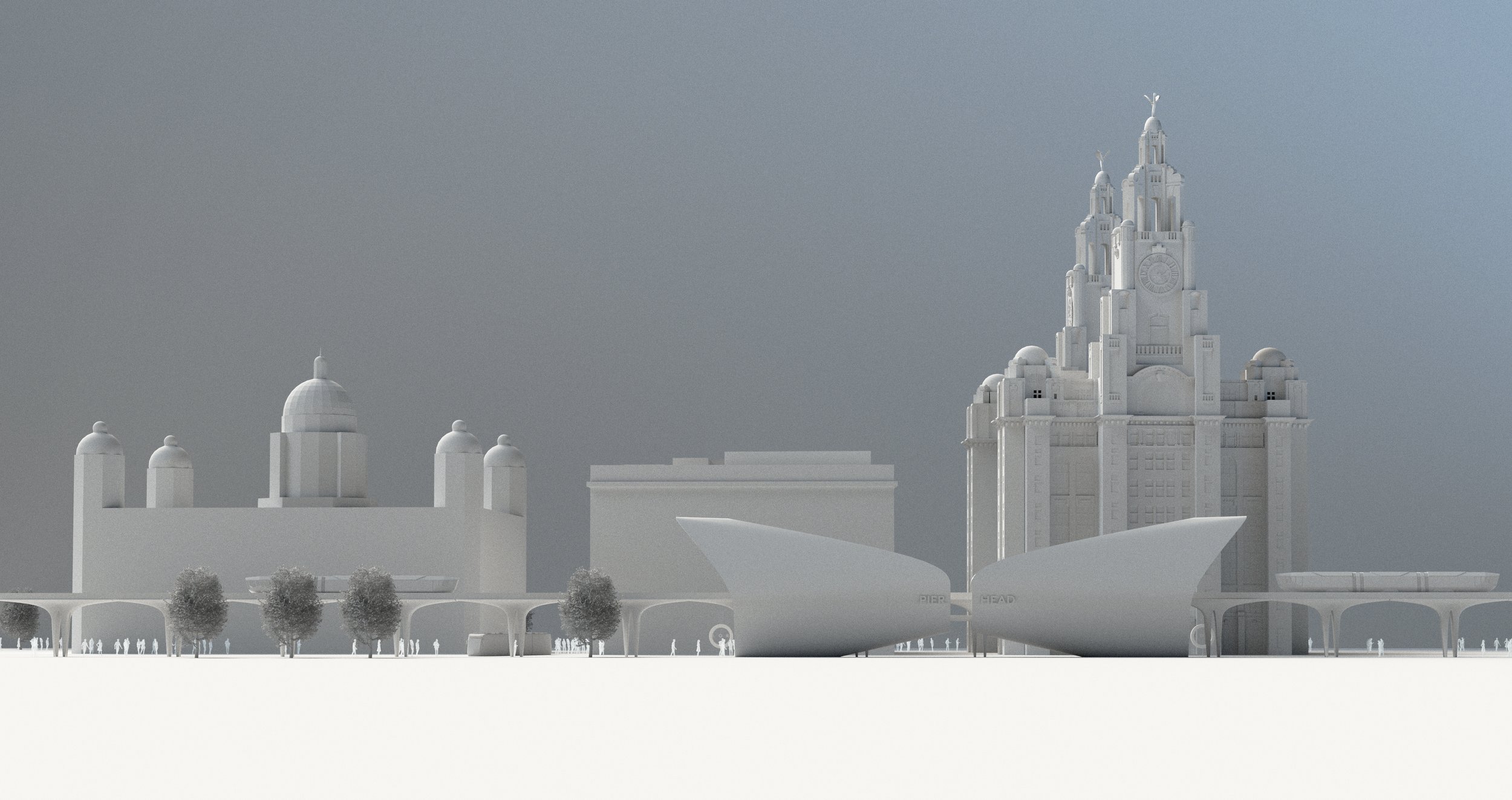

The most obvious location is the site of the now defunct former police station headquarters at Canning Place off the Strand. It’s a big site in a glamorous location with the potential to integrate the city centre more closely with the Baltic Triangle. In scale, Michael is proposing a building similar to the much lauded Copenhagen Opera House, which also has a waterfront setting, but he’s keen to avoid any slavish adherence to ‘context’ – “the space is big enough to create its own”, adding new aesthetic design cues to Liverpool’s urban environment rather than forever replicating (usually in impoverished form) what is already there. For Michael, this means “no warehouse-style blocks, no red-brick, and a departure from straight lines.” Some have said they can see a cobra snake in this design and others an elephant (hopefully not of the white variety). “I didn’t intend either but if they’re there, they’re there,” says Michael. “It’s all about organic, smooth, natural forms.” The final two images in the set, which show the interior of the main auditorium, were created using artificial intelligence more as an experiment in what is possible with the technology.

As an added bonus, Michael is proposing to demolish the John Lewis car park, which adds a “blocky barrier to the growth of the city centre eastwards,” as well as eroding the sense of occasion that this landmark structure deserves. A new solution would have to be found for the bus depot that sits beneath it (not to be confused with the Paradise Street Bus Station which would remain unaffected).

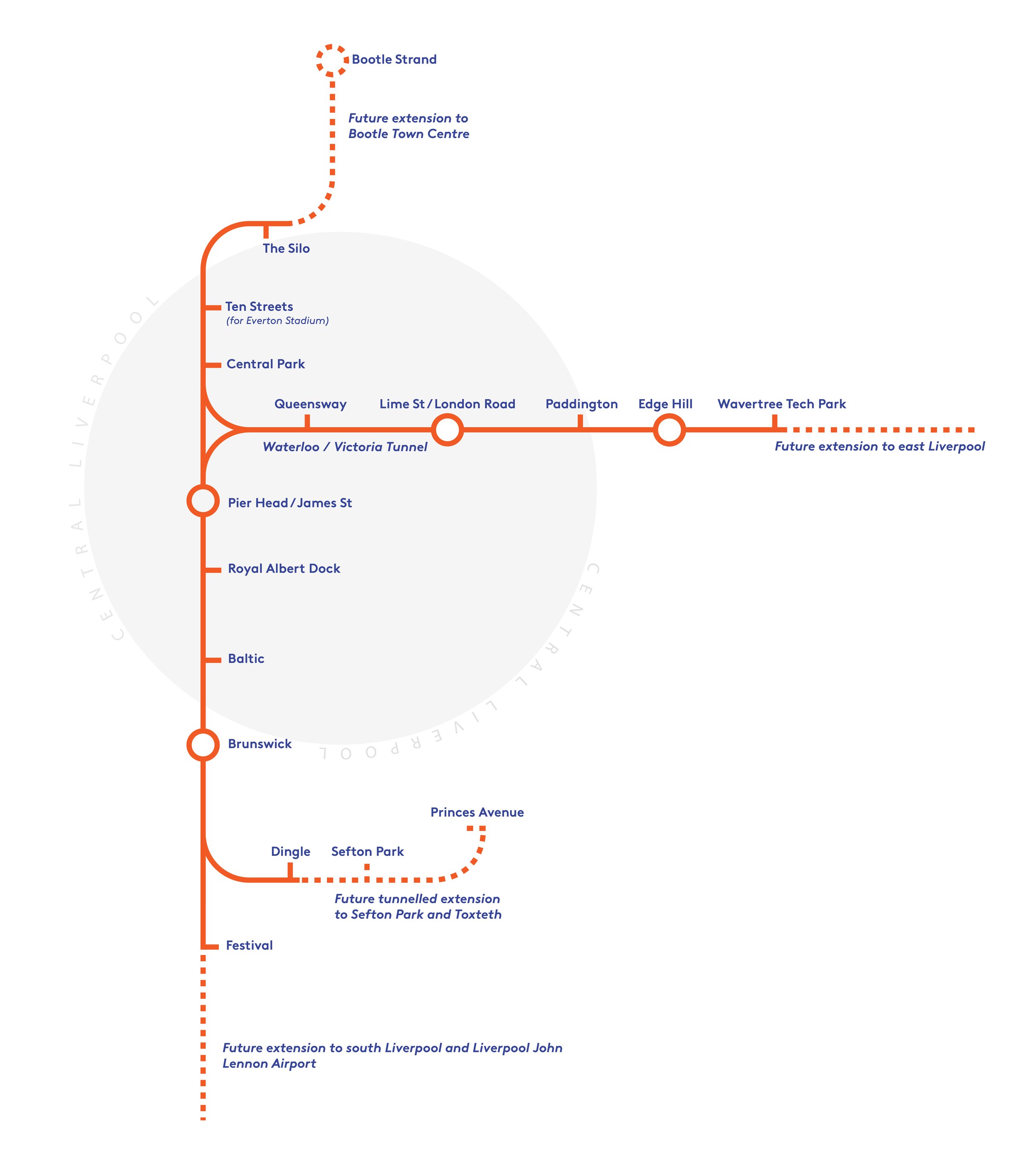

Liverpool Overhead Railway

Many people have long been fascinated by the Liverpool Overhead railway and perplexed by its loss. Extending seven miles along the length of the city’s impressive docklands from Seaforth and Litherland in the north to the Dingle in the south, the line survived for just 64 years before the decline in dock employment ate too deeply into its commuter base. There can be little doubt that if the Overhead Railway had survived into the modern era instead of being dismantled in 1956-57, it would have become another iconic symbol of Liverpool reminiscent of the Chicago ‘L’ trains. Not only that, but it may have long ago expedited the regeneration of the north docks into other uses. Instead, minus viable transport provision, we have had to watch on powerless as docks have lain derelict for decades under the tattered banner of Liverpool Waters.

As much as it’s fun to sit within an old Overhead carriage within the Liverpool Museum (and marvel at its spacious dimensions and varnished wooden interiors), Michael would much prefer to see it rebuilt. The case is becoming stronger with the soon to open Bramley Moore Dock Stadium, the Titanic Hotel and new apartments in the Tobacco warehouse extending the city centre and creating a line of activity to the attractions centred around the Albert Dock.

‘The Liverpool Overhead Railway may have long ago expedited the regeneration of the north docks into other uses. Instead, minus viable transport provision, we have had to watch on powerless as docks have lain derelict for decades under the tattered banner of Liverpool Waters.’

However, Michael says “we cannot and should not merely recreate a pastiche of the old line.” Technology and engineering have moved on, and the old structure was difficult and expensive to maintain. Besides, its heavy-set viaducts blocked views of the river from further inland, which might be unwelcome today. If the city are ever to rebuild the Liverpool Overhead Railway, he feels it should “celebrate the past but not be beholden to it.” A little like London’s Docklands Light Railway (DLR), his version 2.0 is a fully-fledged railway, not a monorail, elevated by organic and elegant concrete columns that avoid the blocky and very nineties form of the DLR design.

To maximise its utility, Michael’s new Liverpool Overhead Railway would not simply follow the old route but would connect more widely. Starting at Bootle in the north to better integrate that area as part of our metropolis, the line would connect the Everton stadium and key attractions centred around the Albert Dock before heading off south to the airport, and perhaps also east via the disused Waterloo or Victoria tunnels. The design of the structure would be modern, and the trains capable of running on conventional tracks (like the recently introduced Merseyrail ones) opening up options for integration with the wider rail network.

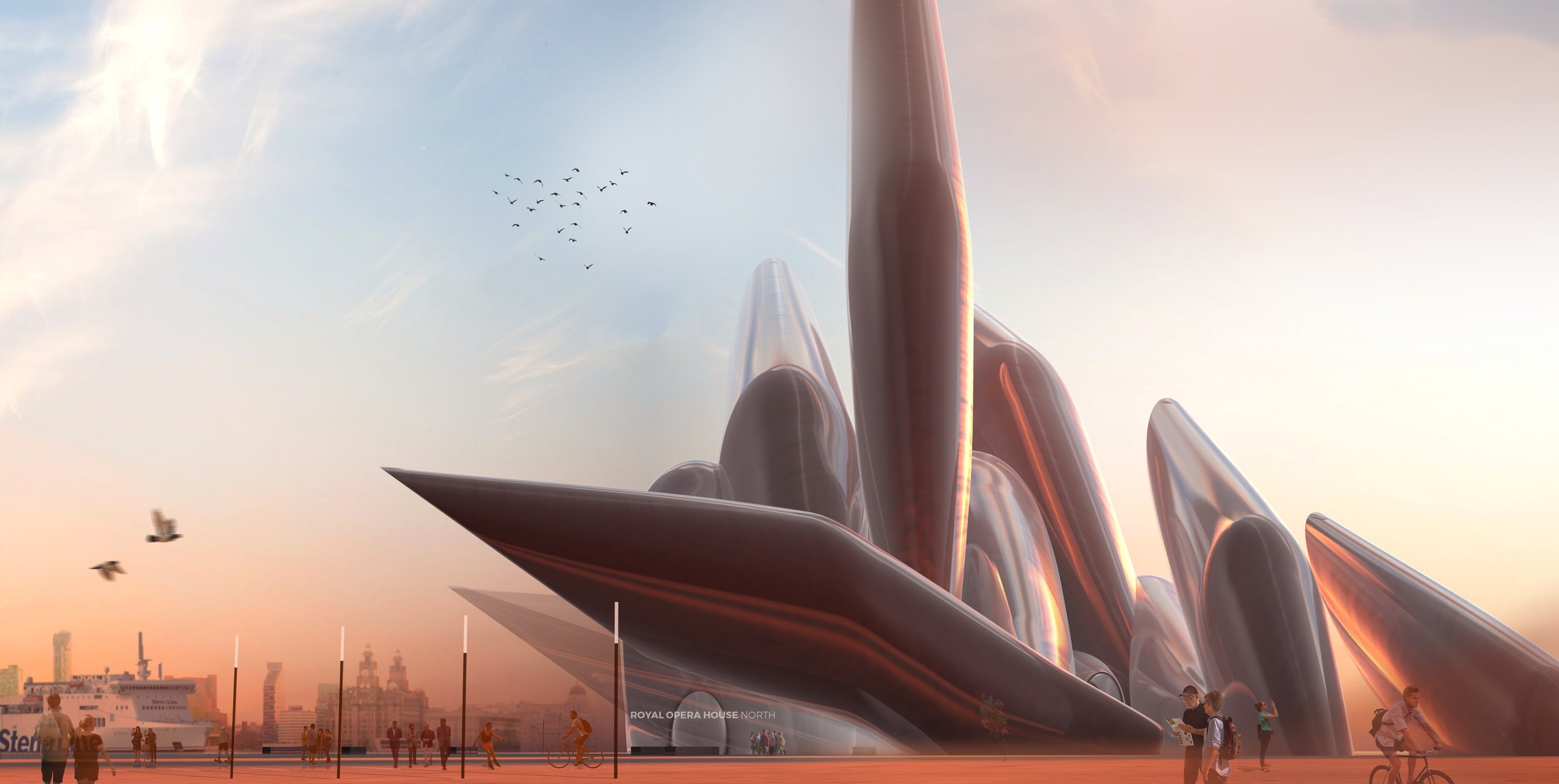

Royal Opera House North & Wirral Cultural Centre

At Liverpolitan, we’ve always believed the Wirral Waterfront to be Liverpool’s great missed opportunity. Overlooking one of the finest riverside vistas in the world, the left bank of the Mersey should be prime real estate, and yet it’s almost apologetically unimpressive – as if frightened to upstage its more famous brother. Surely, we can do better? “People laughed at the idea of Salford Quays hosting the BBC and the Imperial War Museum North,” says Michael, “but with its spectacular setting, the Wirral Waterfront should be aiming higher again.”

Two waterfronts, one city has to be the future but to really make that idea count, at some point we’ll need a significant intervention in the landscape. Wirral Council are doing good work in master planning a new Birkenhead with a better relationship to the river and Liverpolitan is all for it. But to seal the deal, argues Michael, “the Wirral needs something that stands out, something that can be seen from the Liverpool side – something that says ‘Look at me, come over to the Left Bank.’”

Given the 0.7 mile width of the Mersey between Liverpool and Birkenhead, any new landmark structure would need to be huge, gargantuan even. Taller than the 210 feet Ventilation Tower. Possibly taller than the 328 feet Radio City Tower. Cathedral-like in scale and presence. It was along those lines that McDonough put forward this earlier concept for a Royal Opera House North – aligned so that “you can see it as you look down Water Street – the two sides of the river visually connected with an iconic landmark; a catalyst for seeing Birkenhead through new eyes.”

The design is dominated by a series of steel funnels with a glinting chrome façade pointing in all directions of the compass including skyward. They would be wrapped around a central auditorium which could also have uses as a cultural centre exploring the Wirral’s fascinating history from the Vikings to its use as a monastic retreat, not to mention shipbuilding and its colourful background as a smugglers paradise.

‘The Wirral needs something that stands out, something that can be seen from the Liverpool side – that says ‘Look at me, come over to the Left Bank.’

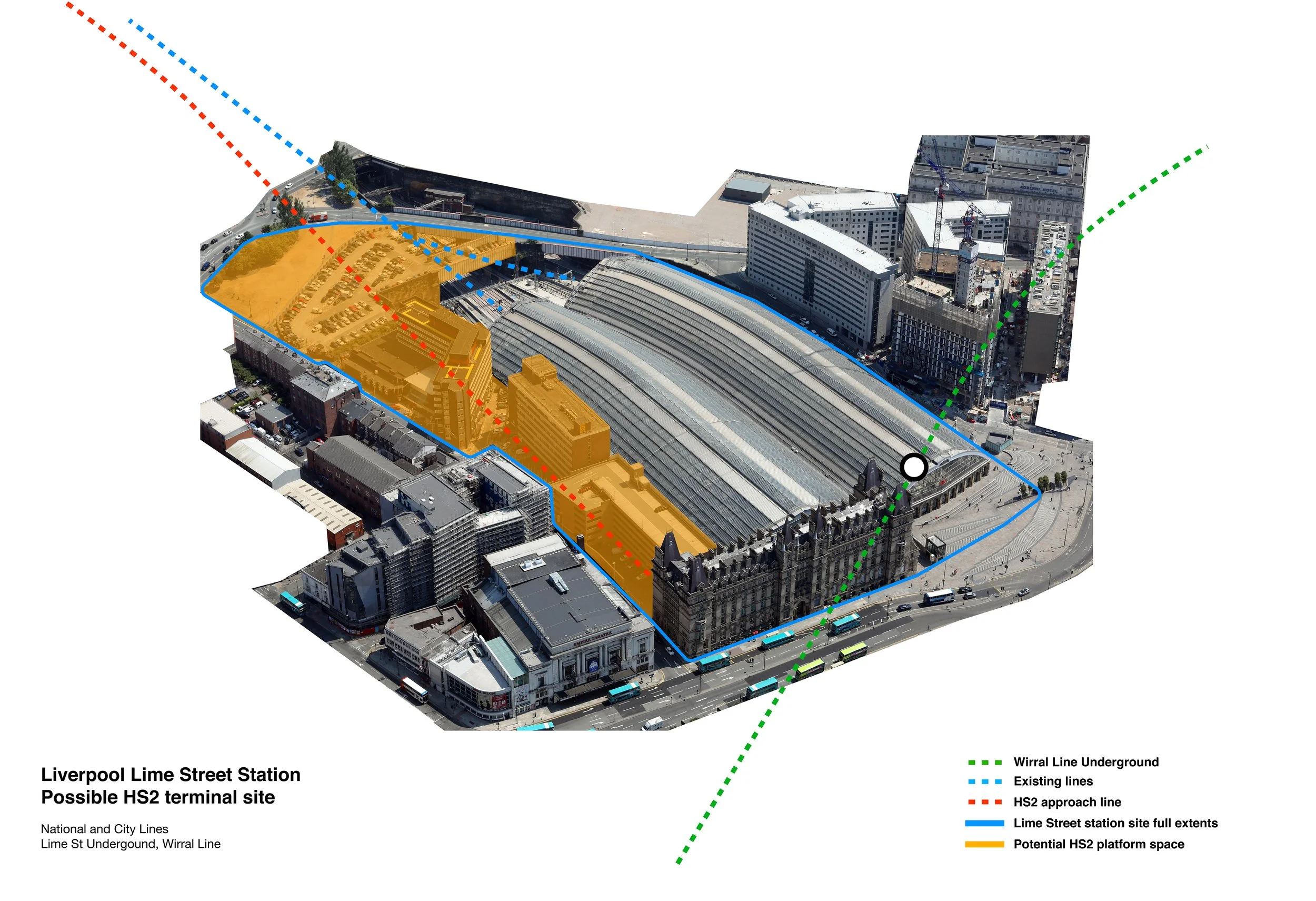

Liverpool HS2

It’s all gone a bit quiet on the High Speed 2 railway project hasn’t it? Maybe that’s a good thing – just get on and build it. But for Liverpolitan, HS2 has always been something of a poker-tell, not so much about the lack of commitment of the national government to invest anywhere outside of the south – which to be honest, we can all take for granted. No, what HS2 really reveals in full technicolour is the shallowness of Northern solidarity – some places, most notably Manchester and Leeds are consistently favoured over others like Liverpool and Newcastle. Despite the sweet words of ‘King of the North’, Andy Burnham, arguments about agglomeration are forever used to draw money and opportunity towards these investment blackholes and away from everywhere else. And HS2 has been the smoking gun. More’s the pity that Liverpool’s own leaders have been too foolish to notice (or they never cared).

When the Conservative government announced the Integrated Rail Plan for the North and Midlands in late 2021, the media was full of a wailing and gnashing of teeth. Cutting HS2’s eastern leg to Leeds and scaling back plans for Northern Powerhouse Rail was seen as more evidence of the perfidiousness of London and Whitehall. Right on cue, Liverpool’s often hapless Metro Major Steve Rotheram, joined in the venting, complaining that “we were promised Grand Designs, but we’ve had to settle for 60 Minute Make Over.”

Not for the first time, a fair reflection of Liverpool’s own particular interests was absent, but with the help of railway campaigners like Martin Sloman and Andrew Morris of 20 Miles More, Liverpolitan spotted it. The truth was, the plan might have been less good for Leeds and Manchester but it was better for Liverpool. Fresh high speed track was going to be laid closer to the city in a dedicated spur that would relieve capacity constraints and increase the scope for an expansion in freight services. In addition, the need to widen the narrow throat entrance to Lime Street was also finally acknowledged. Hurrah!

‘What HS2 really reveals in full technicolour is the shallowness of Northern solidarity – some places, most notably Manchester and Leeds are consistently favoured over others like Liverpool and Newcastle.’

Still, wanting the best for Liverpool means building new track all the way into the city centre serviced by a full specification HS2 station. By the way, what happened to the commission set up by Steve Rotheram in March 2019 and announced with full fanfare at the MIPIM Property Exhibition, which chaired by Everton CEO Denise Barrett-Baxendale, was going to choose between 2 possible locations for a new “architecturally stunning” HS2 station in the city centre as well as 5 routes in for the track? Quietly dropped?

Focusing on the most likely outcome of a redeveloped Liverpool Lime Street, Michael has put together some outline designs, which incorporated the grade-II listed Radisson Red Hotel (previously the North Western Hotel) as the main entrance to the station.

To read Liverpolitan’s cutting dissection of HS2 and the Integrated Rail Plan for the North and Midlands, check out ‘HS2 – A Liverpool Coup?’ by Michael McDonough and Paul Bryan

Or to read Martin Sloman’s examination into the options for a city centre station, try ‘Lime Street or Bust? The Options For Liverpool’s HS2 Station’

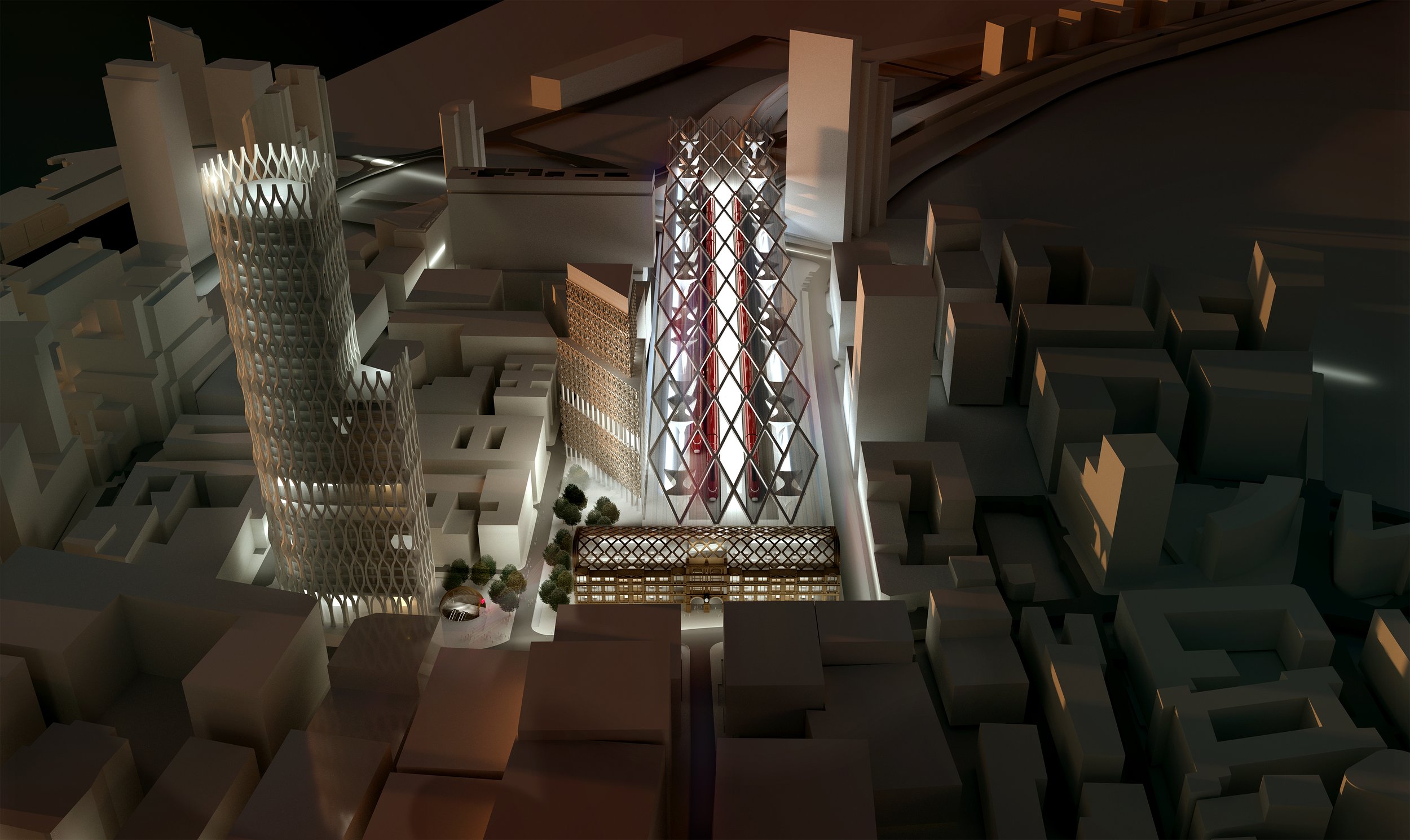

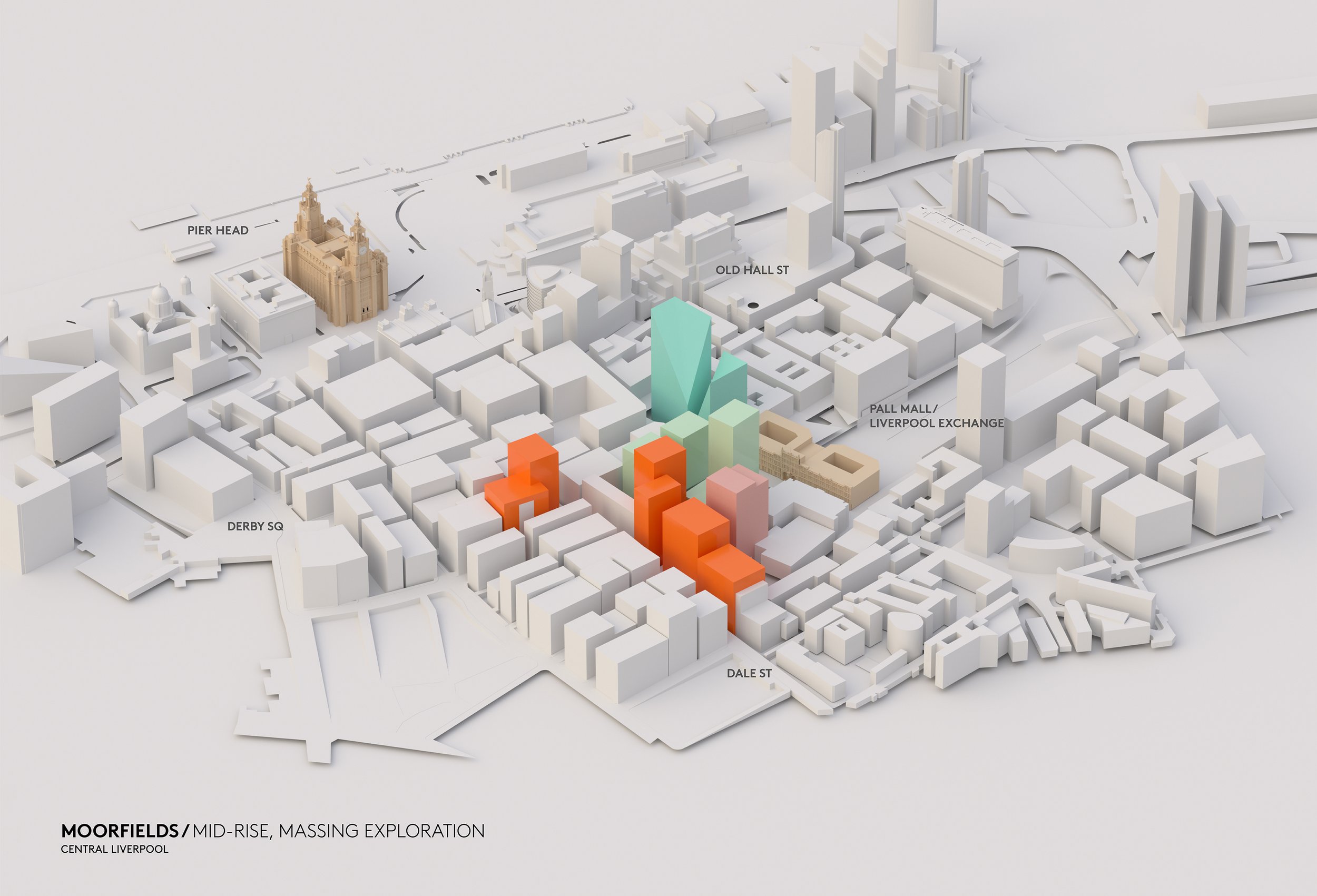

Moorfields and the Commercial District

Back in March 2023, Liverpolitan tweeted about the state of Moorfields, which we described as “a regrettable symbol of Liverpool's down at heel CBD.” We noted that the area is littered with dereliction, empty office buildings and signs of homelessness, and asked the question, “Have we become so used to this embarrassing patch that we no longer see it as failure?”

The tweet received almost 45,000 views and provoked a whole host of online conversation with the issue later picked up by the Liverpool Echo. Councillor Nick Small, who after the recent local elections is now the city’s Cabinet Member For Growth and the Economy, got involved, agreeing that the site needs to be developed. There was some discussion about whether robust plans for the area were in place already as part of the City Centre Local Plan and Strategic Investment Frameworks (SIFs). But mostly, to the extent that the local BID or the Council have acknowledged the issue, action on the ground seems in short supply.

To some extent, the lack of regeneration may be an issue of plot owners sitting on parcels of land and waiting for a payday, but as a subsequent squabble between Merseyrail and the Council over who was responsible for cleaning the grotty Moorfields escalator showed, a lack of concerted coordination between agencies leaves ample scope for things to fall between the cracks.

Moorfields is littered with dereliction, empty office buildings and signs of homelessness. Have we become so used to this embarrassing patch that we no longer see it as failure?

Michael McDonough argues that Moorfields is another of Liverpool’s great missed opportunities and it’s hard to disagree. The area’s city centre location, great transport links, and historic setting within the traditional heart of Liverpool commerce, should with the right support, allow it to live again. “The whole area needs re-invention and the drift towards noisy bars and tourism serves to cheapen its prospects,” says Michael. He claims that demolishing the rotten Yates Wine Lodge should just be the start. “Moorfields can handle density and scale and is the perfect place to rebuild Liverpool’s grade-A office offer” centred around the idea of prestige and talent.

In these visuals, Michael wanted to rebuild the entrance to Moorfields Station with mid-rise commercial office space above – no more going up to go down. He also took a stab at upgrading the former Exchange Station offices, which “may have been grand from the front, but from the rear leave a lot to be desired” – failing to properly address the park that will hopefully one day be re-instated as part of new public realm within the wider Pall Mall development.

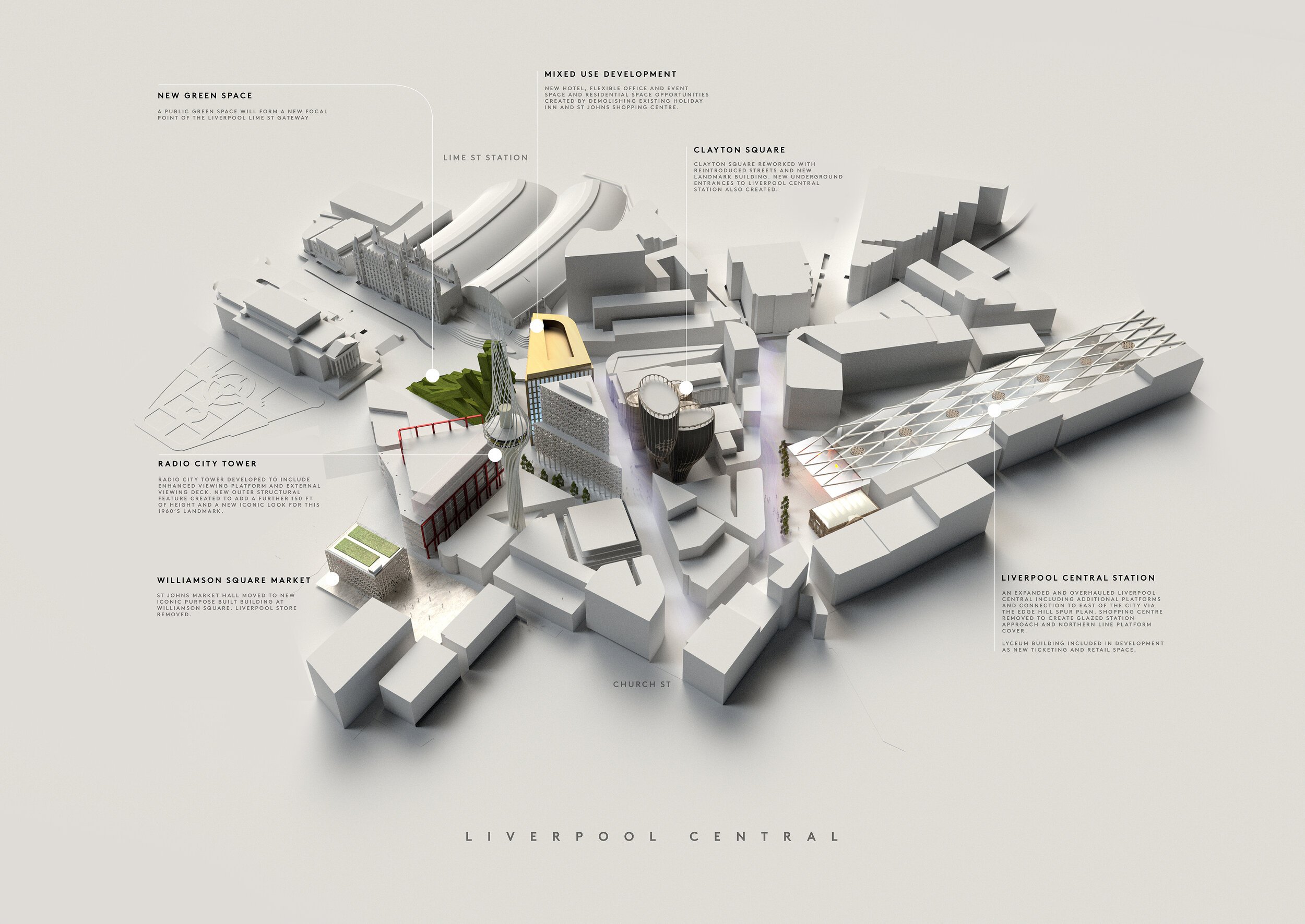

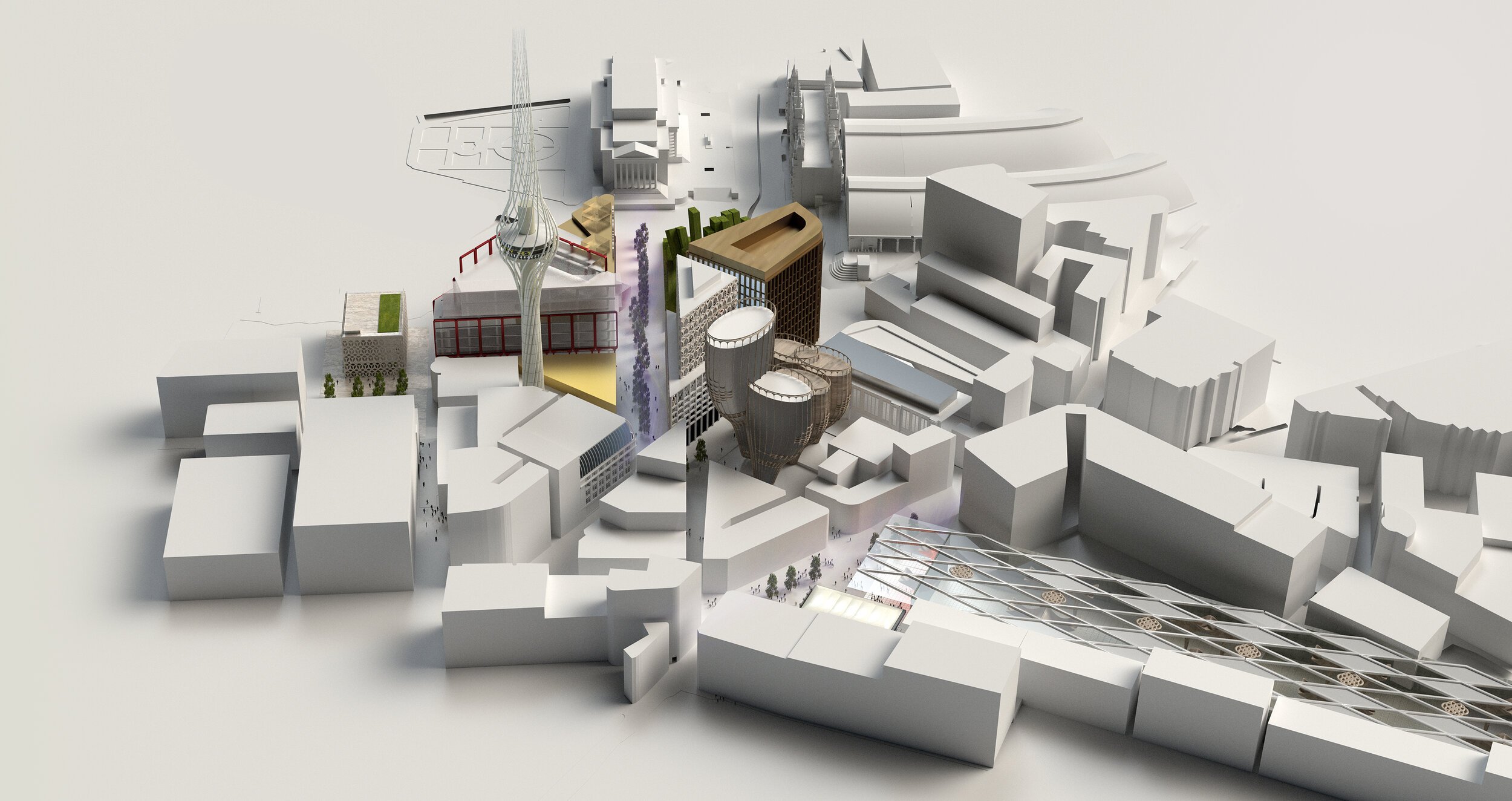

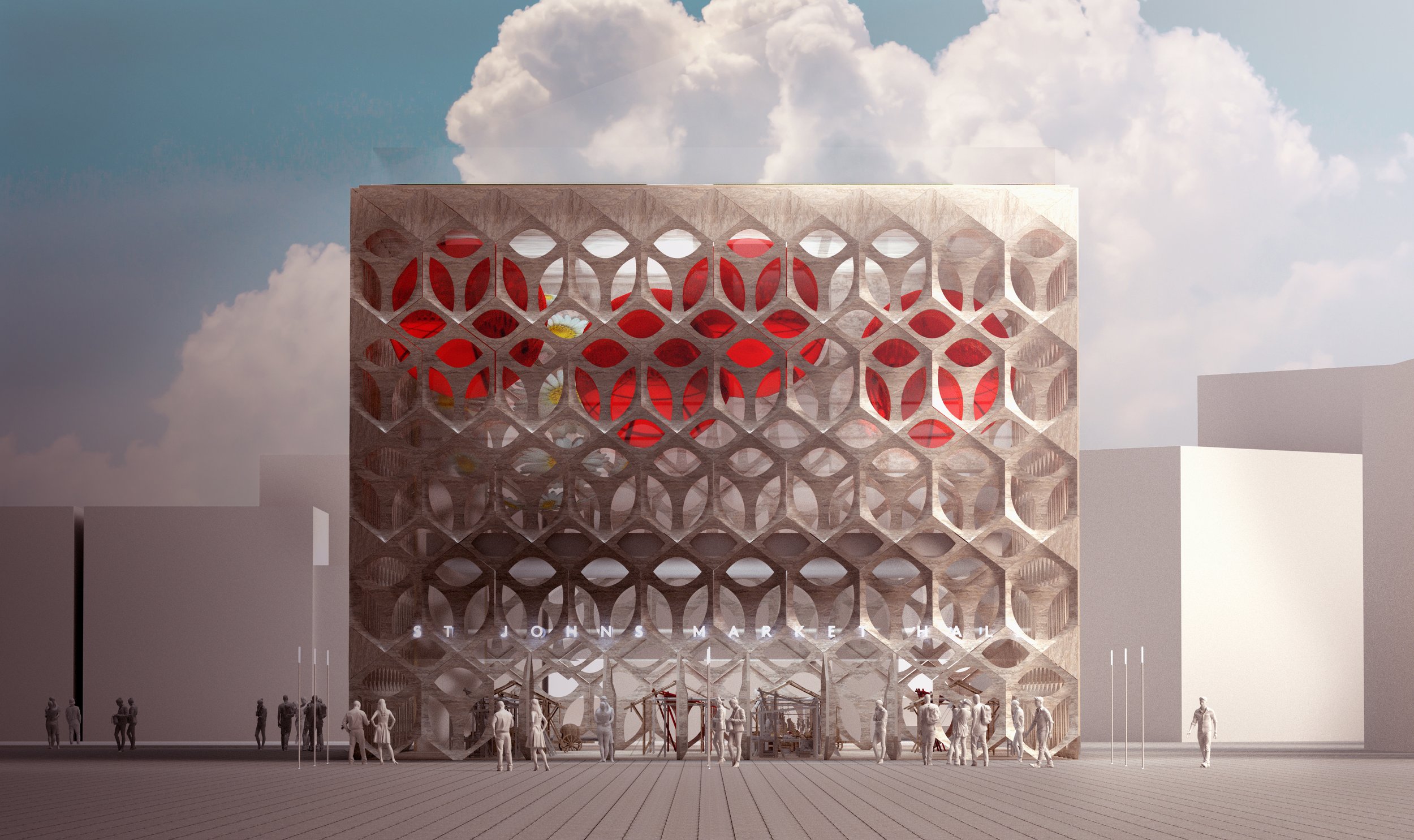

St Johns and Central Liverpool

Far, far and away McDonough’s biggest bugbear with Liverpool’s built environment has to the St Johns Shopping Centre. We know it’s commercially successful and last time we looked it had a 97% retail occupancy rate. It clearly fills an important niche within the city’s shopping offer with its cheaper rents for retailers. But damn if isn’t an ugly pig of a building (no offence to our porcine brethren). Arriving at Liverpool Lime Street, that’s the first thing you see. Talk about first impressions. Squatting over a network of old streets and the site of what would be today, if it hadn’t been bulldozed, a much valued Victorian market, Michael believes St Johns is a “dated lump of a building that acts as a physical and psychological barrier between London Road and the rest of the city centre.” It’s not a stretch to suggest that St Johns has played a role in the former’s decline. Repeated, half-hearted attempts to patch the shopping centre up have failed and its blue plastic blanket and struggling traders’ market are a testament to “a succession of bad planning decisions going back fifty plus years.” A lasting solution to all of these problems, says Michael, “requires demolition.”

The images Michael has put together here are a collection of different attempts to reinvent this “ugly and misfiring section of Liverpool.” The main driving force behind his designs is a desire to remove this “lumpen barrier” and re-stitch together our centre “in a more permeable way that evokes expressions of pride rather than cringes.” Michael wants to see a much better front door to Liverpool Lime Street – our city’s once grand hello and goodbye point. He’d like to replace this “parody of the city’s greatness” with something more iconic and ambitious.

‘St Johns is a dated lump of a building, its blue plastic blanket and struggling traders’ market a testament to a succession of bad planning decisions going back fifty plus years.’

The eagle-eyed might spot the use of neon and a prominent clock tower as a modernised callback to what the site has lost. As Michael says, “we can’t always recreate the past but we can be inspired by its best bits.” He’s also given the Grade 2-listed but still a bit ugly, Radio City Tower, a makeover, adding an elegant polished steel lattice of radiating lines which add height, fluidity and tricks of light to recast a regional landmark into one of world significance.

Read more about Michael McDonough’s vision for St Johns in the Liverpolitan feature, A New Central Liverpool.

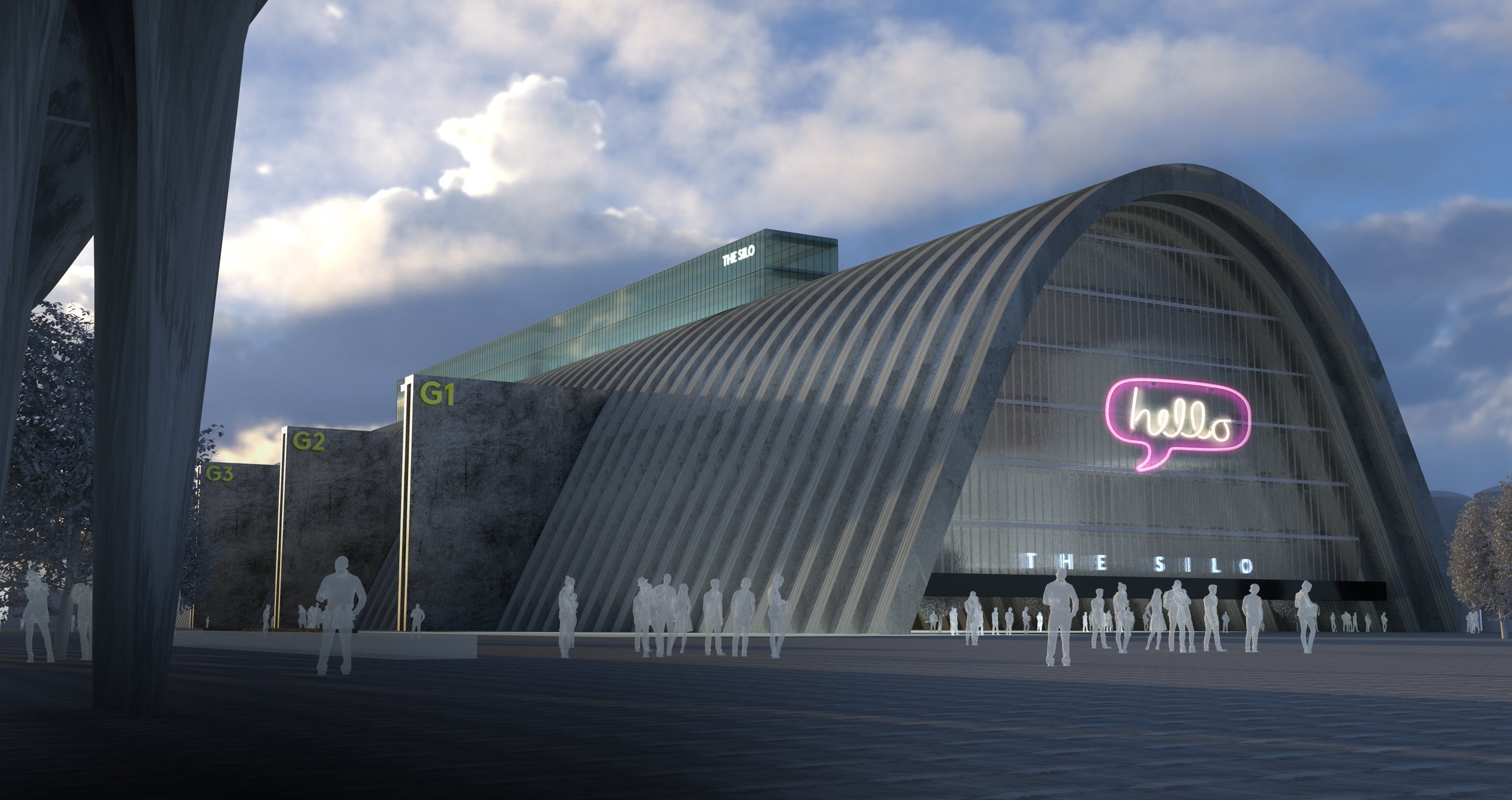

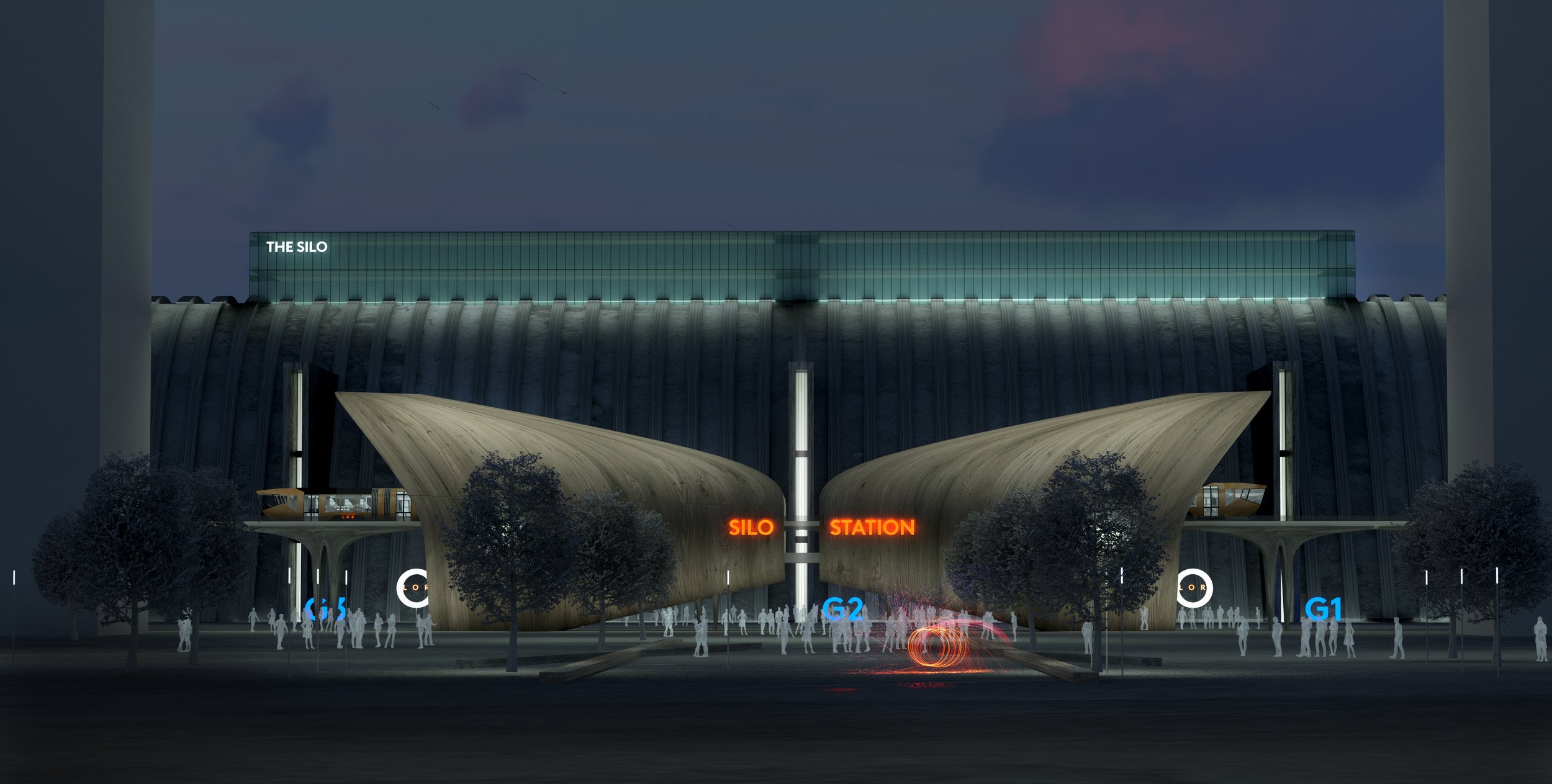

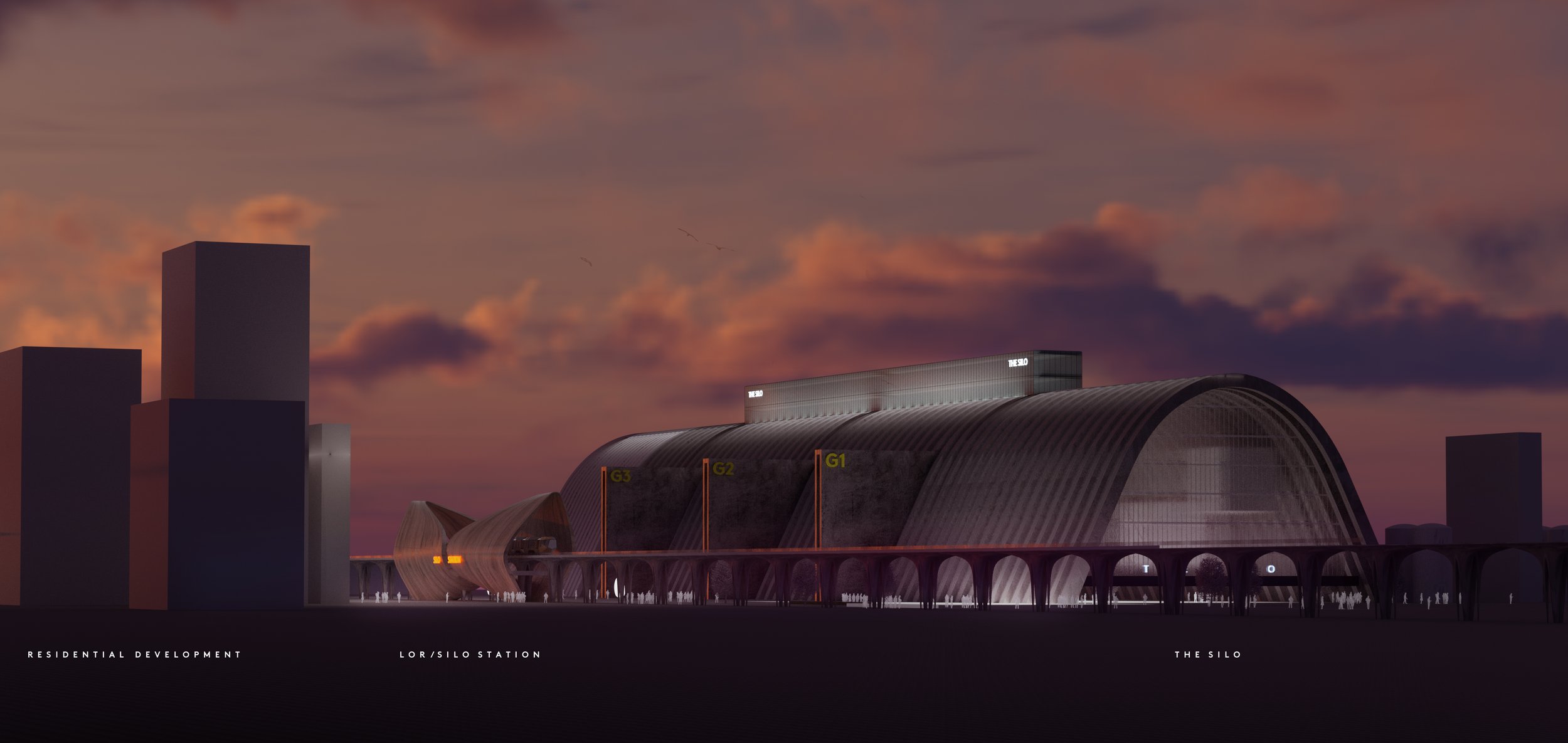

The Silo

The former grain silo in the north docks is one of Liverpolitan’s favourite buildings in Liverpool. If it was just a little further south, closer to the Tobacco warehouse and Bramley Moore, we could imagine it being repurposed as a truly iconic, high capacity arts, events and business hub. However, the silo is located deep within the working part of the dock estate with industrial infrastructure all around it, so that idea is likely to remain a dream. Still, just imagine what could be done with this incredible structure. For McDonough, the project would “represent a development challenge similar to how London’s Bankside Power Station was transformed into the Tate Modern.”

For these visuals, Michael has re-imagined the space as a media industry hub – with film, TV and radio studios and education space for our universities – “a back-up plan in case the Littlewoods Film Project doesn’t deliver.” There would also be a theatre venue, gallery space and office facilities for the production sector – which he describes as “the perfect tonic to act as a catalyst for the regeneration of North Liverpool.” Another possible use, he suggests, might be a central hub for burgeoning logistics businesses if the new Freeport ever takes off. As you can see, Michael has taken the liberty of re-instating the Liverpool Overhead Railway, with ‘Silo Station’ ready to whisk visitors straight to the doorstep.

‘What Michael is attempting to do with these designs is to remind the city that it’s capable of bigger ideas, capable of re-imagining itself, capable of statement architecture, and capable of challenging its city rivals.’

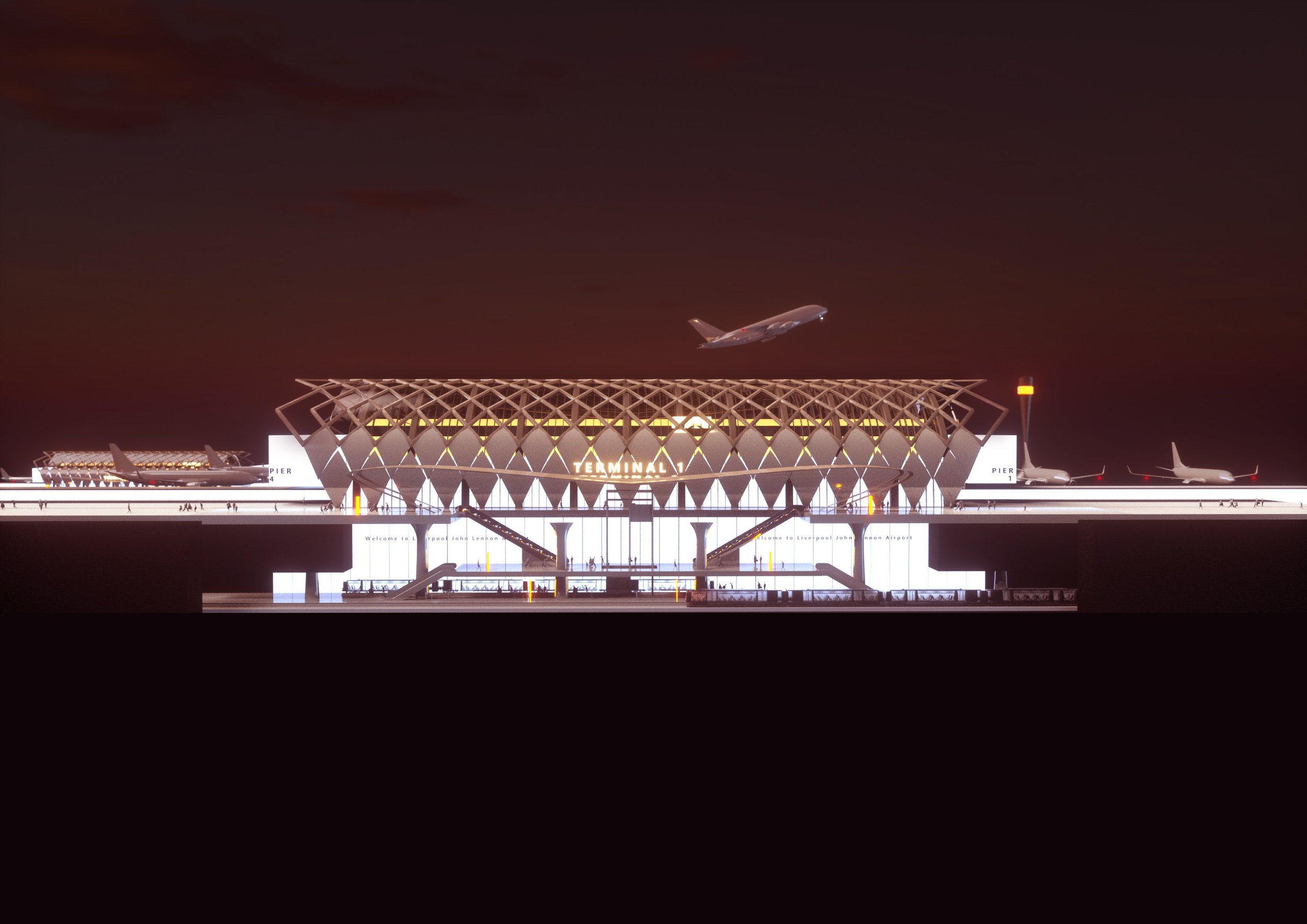

Liverpool John Lennon Airport

Not for the first time, Liverpool John Lennon Airport finds itself in a strange position. Back in the years following World War 2, JLA (minus the Beatles moniker) lost its opportunity to become the north’s most important airport when the Ministry of Defence, which had requisitioned it for the RAF, sat on the asset while its Manchester rival grew. It’s been an uphill struggle ever since.

Not that Speke Airport, as some still call it, hasn’t had its days in the sun. For a time in the early 2000s, Liverpool was THE favoured location for budget airlines in the northwest as passenger numbers ballooned from 0.6 million in 1997 to 5.5 million in 2007. That growth stalled as its much larger rival came to its senses and stopped turning its nose up at budget travellers. Still, JLA has remained a valuable strategic asset for the city, and despite the devastating blow that Covid dealt to its passenger numbers and its finances, the airport is making a solid recovery. Finally free of the dominant stranglehold of Ryanair and Easyjet, the airport is now diversifying its offer, attracting new airlines such as Lufthansa, Air Lingus and Wizz Air. And JLA continues to pick up a steady stream of awards for the efficiency of its operations, where queues tend to be largely absent.

Sad then, that Liverpool Airport has found itself consistently under attack in recent years from local environmental activists such as Liverpool Friends of the Earth and the Save Oglet Shore campaign group, who appear to want to make an example of it, by opposing all possible expansion. In fact, it’s been pretty clear in Liverpolitan’s own Twitter debates with these groups that there are those who would like to see the airport closed altogether – its miniscule contribution to the nation’s CO2 output too much for some. Others claim the farmers’ fields to the south are too ecologically important to lose or that air quality is impacting the health of local residents – the result in part of some very strange and short-sighted choices by the Planning Department on where to locate new residential developments. Inexplicably, our council continues to have a very ambivalent attitude to what should rightly be viewed as a key enabler of our economic prosperity.

‘The reality is, the healthy human desire to travel and see the world will not and should not be legislated away by those with a dystopian vision of the future.’

The reality is, the healthy human desire to travel and see the world will not and should not be legislated away by those with a dystopian vision of the future. The technical challenges to realising a cleaner way to fly are immense, but they are not uniquely Liverpool’s burden and no other city would so blindly hobble itself in restriction.

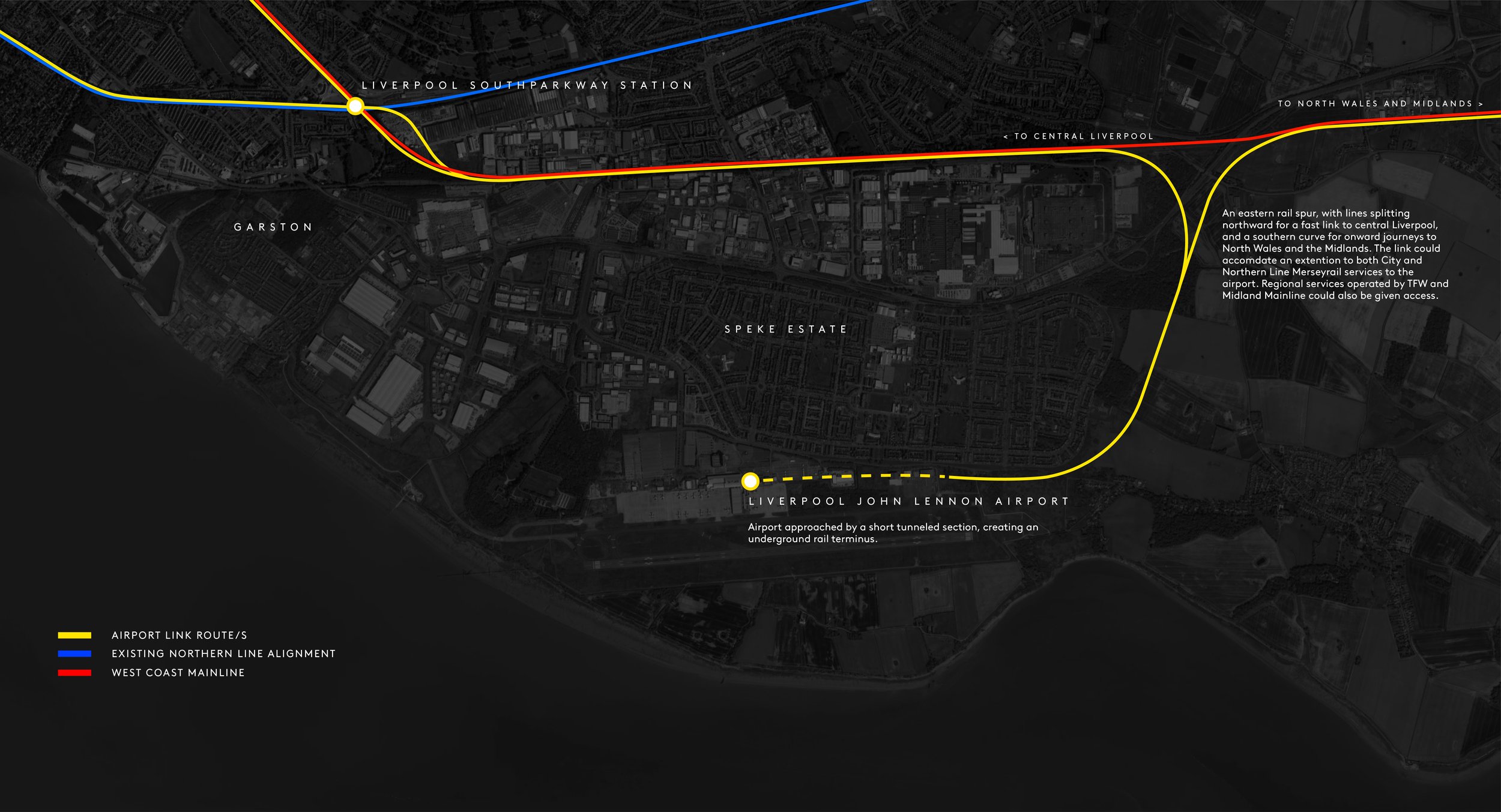

Michael McDonough grew up next to Liverpool John Lennon Airport and has seen its infrastructure grow from “a small, bland, industrial shed of a terminal into something more befitting,” and at some point in the future he believes it will need to expand. Michael argues that better public transport provision should be a priority with an extension of the Northern line or a tram connection mooted as alternatives. In these designs, Michael has proposed a train line that tracks underground for the final few hundred meters to arrive directly at a much expanded terminal. The capacity of the current structure is around 7 million, so if JLA can hold onto its post-Covid gains and continue to build upon them, discussions about what comes next will be inevitable. “The myopic few who claim the northwest already has a large airport and doesn’t need another, are shutting their eyes on the obvious.,” says Michael. “Demand for flying will continue to rise and the north can easily sustain a larger Liverpool John Lennon Airport at Speke.”

Northern Assembly

Given the shenanigans at Liverpool City Council in recent years, it might seem strange to suggest our city as the seat of political governance for the whole of the north. But a Labour government is a distinct possibility come 2025 and they’ve often flirted with the idea of greater regional devolution and a northern assembly to govern our unruly mob. Manchester is the usual default option, of course, but at Liverpolitan we can’t be having that. Perhaps only Newcastle can offer the grandeur of our riverside estuary setting here on the Mersey. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Liverpool took inspiration from its darkest days to become a paragon of democratic values? To take accountability and citizen engagement as its governing principle, to put behind it the days of boss politics and party before city, and instead show the world how local government is done when at its best.

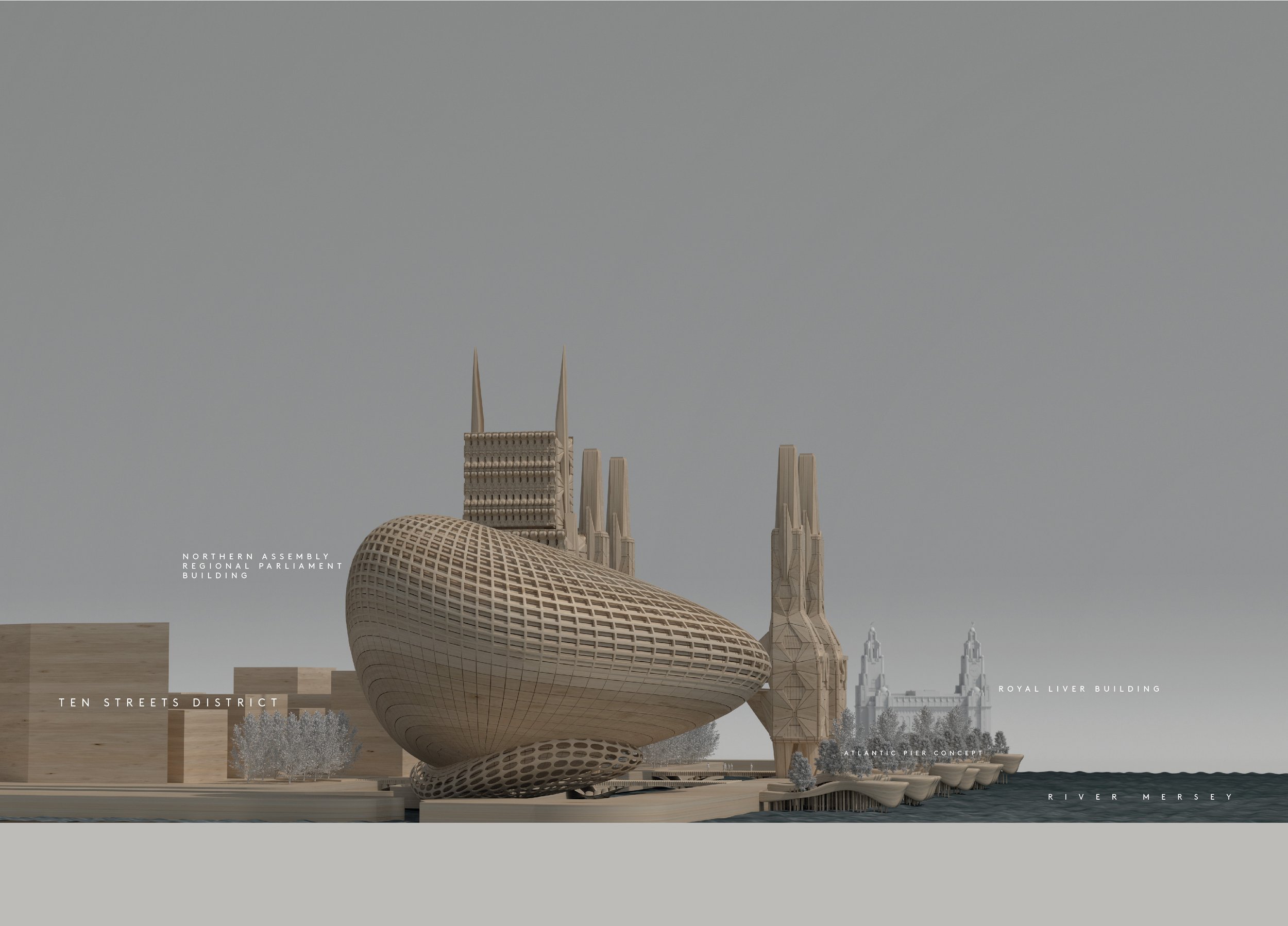

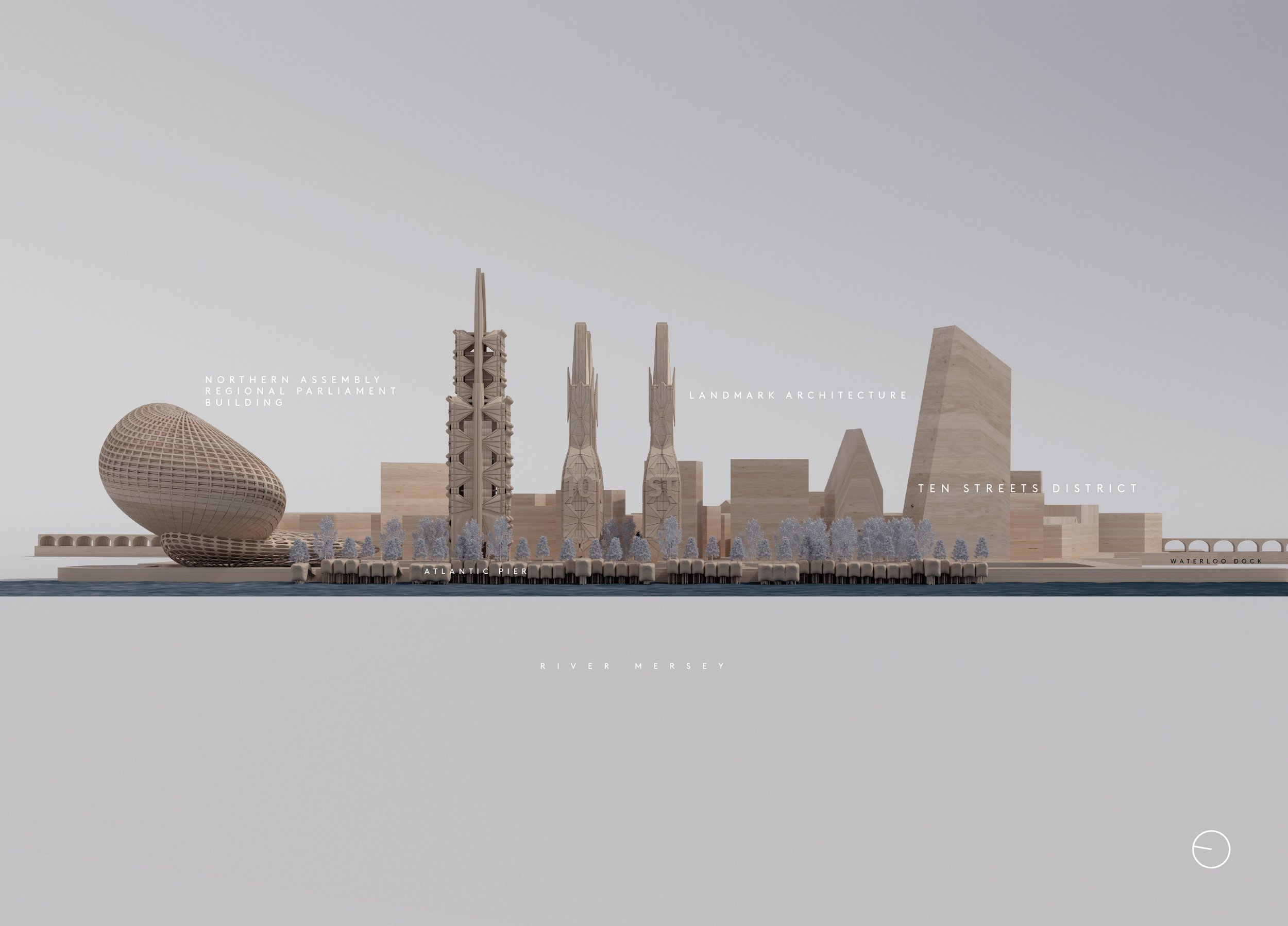

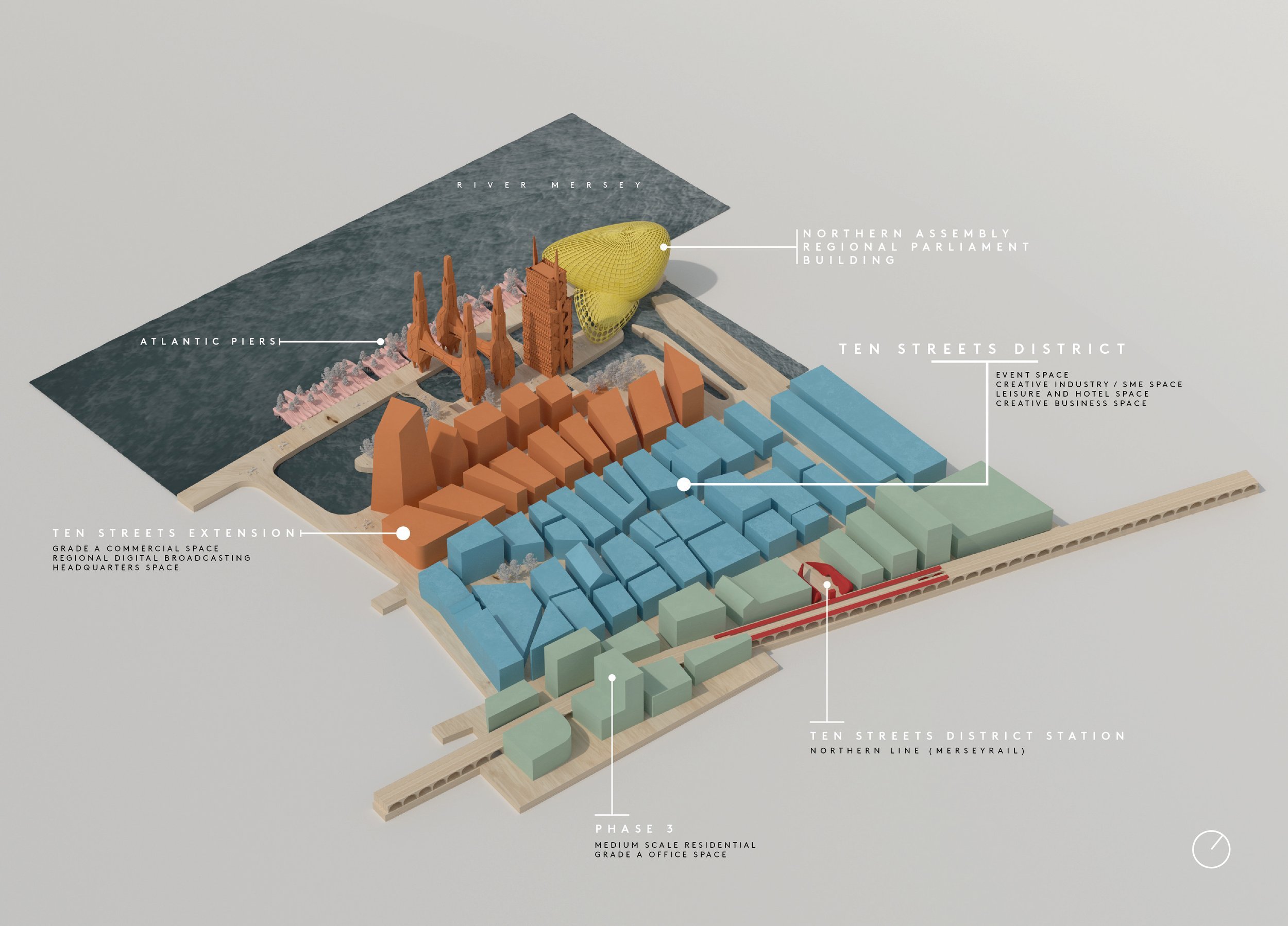

McDonough’s design of a new Assembly district is based on a wholly different concept to Peel’s current underwhelming plans for Liverpool’s central docks – albeit quite capable of incorporating a sizeable, new park. The site encompasses a parliament building, ancillary office space, a new cultural centre with notes of modern gothic and an extension of a revitalised mixed-use Ten Streets area including substantial residential to repopulate the area and give it life. In these days when the potential for terrorist attacks is sadly a design factor, Michael believes the location’s riverside setting has unique advantages, making it defensible for security services. Addressing concerns about the loss of ‘blue space’ at Waterloo Dock, he has increased the provision of waterways by reclaiming some of the infilled land, and bridging buildings across it. This Michael explains is “meant as both a symbolic and practical gesture of compromise in a city often at loggerheads with itself on how to reach for the stars architecturally without compromising existing heritage elements.”

Naturally, this substantial expansion of our city centre, requires transport infrastructure, which Michael has designed in with a new station at Vauxhall on the Northern line. Such investments in transport become more viable as we add additional all-year-round uses instead of just relying on the footfall that the new Bramley Moore stadium will provide.

‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Liverpool took inspiration from its darkest days to become a paragon of democratic values? To put behind it the days of boss politics and party before city, and instead show the world how local government is done at its best.’

For a fuller exploration of this concept, read Michael McDonough’s Liverpolitan feature, Welcome to the Assembly District.

Liverpool Central Station

The redevelopment of Liverpool Central Station has long been on Merseytravel’s wish list and it’s not hard to understand why. Boasting the highest passenger numbers of any underground station in the UK outside of London, Liverpool Central is, despite recent minor refurbishment, “a dark, dated and cramped station prone to over-crowding,” according to Michael. Its current single island platform structure and track layout on the Northern Line section also places restrictions on train capacity. A full scale expansion of the station, which the Liverpool Combined Authority are pushing central government for, would allow more trains to run through services linking up the Northern and City lines via a re-used Wapping Tunnel. This would in turn free up capacity at Lime Street Station enabling it to focus on its role as an intercity and regional transport hub.

A few years ago there were grand plans to convert the old Lewis’ department store which sits next to Central Station into a new shopping centre accommodating new residential blocks. A side benefit of the scheme was the use of Lewis’ ground floor to open up a new, additional entrance to the station itself. However, the proposed scheme, which ultimately came to nothing, left intact the tired, almost prefab current station entrance – “a pale shadow of what was once a magnificent Victorian railway terminal,” says Michael.

McDonough believes that when the time comes to rebuild this thing, we should “go all out and design a station that lets in the light.” These visuals imagine a doubling in the size of the station envelope, with an additional platform, and the complete removal and replacement of the shopping arcade with a dedicated railway concourse at the street level front end. The plan would allow the floor above the underground platforms to be removed allowing sunlight to reach down to create a much more welcoming environment. Reinforced as a major local transport hub for the city, and with the poorly performing shopping centre now gone, Michael believes the wider site offers potential to “accommodate new office and residential accommodation at impressive scale.”

‘The proposed scheme, which ultimately came to nothing, left intact the tired, almost prefab current station entrance – a pale shadow of what was once a magnificent Victorian railway terminal.’

New Brighton Pier and Observation Tower

The advent of foreign travel certainly did for many of Britain’s seaside resorts. Still, nostalgia aside, glancing through old photographs of New Brighton does makes the heart bleed for what was lost. It’s hard to think of a more striking example of the region’s self-destructive attitude towards its built environment than the loss of the old ballroom and tower, fire or no fire. Not to mention its pier, pleasure grounds and lido. Daniel Davies of Rockpoint Leisure has been doing his bit in recent years to bring a bit of hip to Victoria Street and the Championship Adventure Golf course is well worth a visit too. In fact, there are tentative signs that Wirral Council are starting to understand what they have, even if the area has been stripped of many of its key attractions. Liverpool’s Left Bank can and should be a treasured beauty spot, a place for families to enjoy and a haven for the avante garde and edgy. Now is the time to think bigger.

Michael hasn’t yet worked on a full plan for New Brighton but bringing back some kind of landmark beacon with a viewing deck, visible from the other side of the Mersey and prominent to the passing cruise ships feels like it should be part of the picture. Back in the early 2000s, sculptor Tom Murphy proposed a 150-foot statue of the Roman god, Neptune, to sit in the waters at the mouth of our mighty river – Liverpool’s equivalent of the Statue of Liberty or the Colossus of Rhodes. Oh, how we’d like to have seen that! Or if money was no object, two of them either side of the river standing proud like the Argonaths of Lord of the Rings. In the meantime, Michael McDonough took a stab at a slightly less monumentalist beacon a few years ago.

‘Back in the early 2000s, sculptor Tom Murphy proposed a 150-foot statue of the Roman god, Neptune, to sit in the waters at the mouth of our mighty river – Liverpool’s equivalent of the Statue of Liberty or the Colossus of Rhodes.’

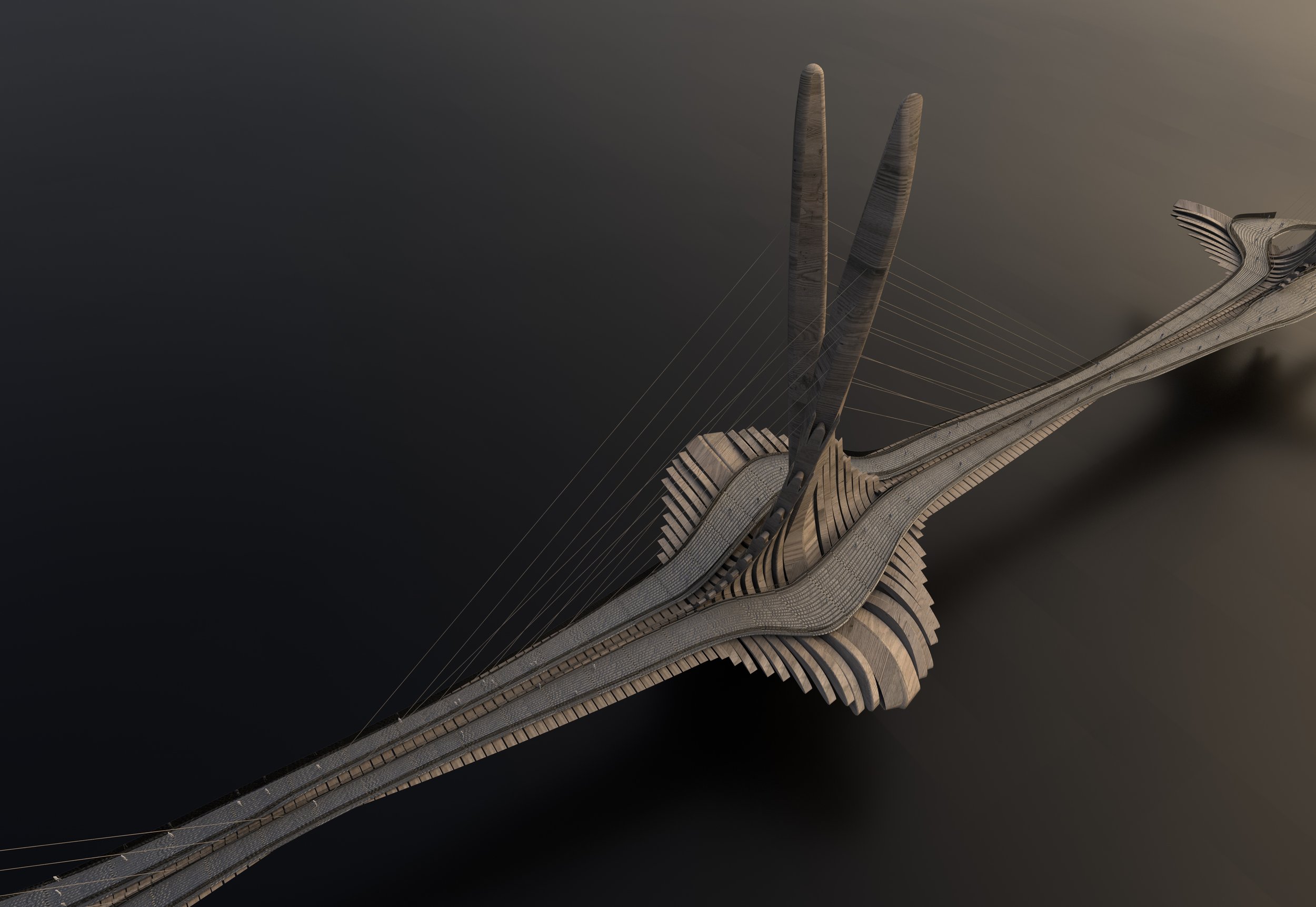

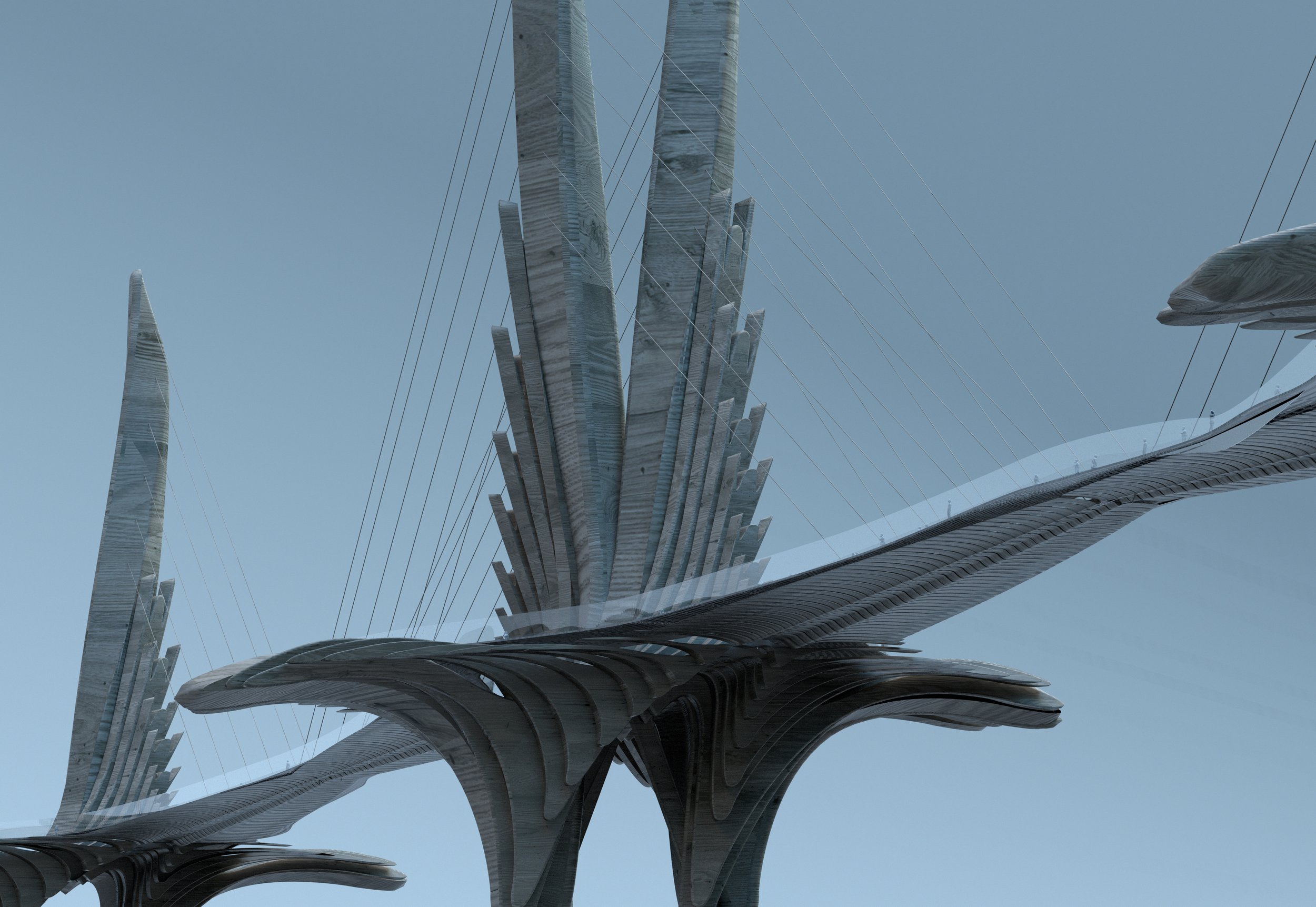

The Liverpool ‘Angel’ Bridge

Unashamedly a flight of fancy and almost certainly the most outlandish of McDonough’s ideas, the concept of a bridge linking Liverpool and Birkenhead delivers an element of San Francisco’s Golden Gate magic and then tries to one-up it. There’s something slightly Game of Thrones about this design, which Michael says he wasn’t consciously thinking about at the time. “It’s intended as statement architecture,” says McDonough, “A big ‘Here I am’ to the world that would forever add a new image to the iconography by which Liverpool is known.” The idea behind it is to unlock the two sides of the Mersey as one urban centre, transforming Birkenhead’s prospects for the better. It would, of course, be ludicrously expensive and so is likely to remain one for the mind’s eye. “Building this kind of structure would take serious doses of civic ambition and that’s the kind of vision we don’t often see in these parts,” said Michael.

For those worrying whether the bridge would undermine the Mersey tunnels, it has been designed as pedestrian-only, although it could be adapted to accommodate light rail or electric tram-buses. In terms of location, on the Liverpool side, Michael imagines it would sit between the Albert Dock and the Museum of Liverpool, while over at Birkenhead, the bridge would land at Woodside, right next to his alternate proposed site for an Opera House North.

“It’s intended as statement architecture”, says McDonough, “A big ‘Here I am’ to the world that would forever add a new image to the iconography by which Liverpool is known.”

…and finally.

Project vision and designs by Michael McDonough. Article by Paul Bryan.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Introducing the Assembly District

History teaches us that no matter which party is in power in Westminster, only the north can be trusted to look after the north. But it should also teach us that the politics of agglomeration are divisive and will not end well for anyone but Manchester and Leeds. But never fear, Michael McDonough offers a solution - tearing up our current constitutional arrangements and establishing a new Northern Assembly for all of the north located on the banks of the Mersey. And he’s only gone and designed it … welcome to Liverpool’s new Assembly District.

Michael McDonough

Quite how Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham came by his coronation in the media as ‘King of the North’ is subject to conjecture.

Some such as journalist and author Brian Gloom speculate that it started as an internet meme, while others wonder whether it was a creation of Marketing Manchester, an agency never shy to position it’s home city as the centre of everything. Whatever its source, and Burnham has himself joked about ruling from a Game of Thrones-style castle, like all good observation comedy, its absurdity is centred on a degree of truth. You’d have to have been operating with your eyes closed since at least the emergence of David Cameron’s government in 2010, not to pick up the sense that Manchester has become the increasingly less unofficial capital of the north, much favoured by business, government ministers and media alike. It’s hard not to notice that whenever the north’s regional mayors get together for a photo op or conference, it’s Burnham that is usually centred as the pivot point around whom others orbit.

You could say this position is much deserved. Over several decades Manchester has played a very successful and canny game and has done much in the running of its economy that is both admirable and instructive to other regions with ambitions to raise their own performance. But this article is not intended as a Manchester love-in. The fear from the outside is that other regions, most notably its closest neighbour Liverpool, are caught in something of a gravity well, heading towards the event horizon, where the blackhole sucking in wealth and talent becomes inescapable.

The UK government appears to have been operating a policy known as agglomeration where the economies of towns increasingly centralise around cities, and the economies of cities are pulled towards the biggest and best of them. The idea is that a northern London will offer snowball effects that drive increasing productivity and opportunity. Any attempt to discuss the downsides are quickly dismissed as jealousy. But what happens to everywhere else? As any real political or investment efforts become increasingly centred on Manchester and Leeds, the north’s other towns and cities are forced to focus on more tertiary and lower value economic sectors to avoid this very obvious elephant in the room. No wonder there’s much discussion about transport. You need good trains and good roads to create a commuter belt.

Whether the north actually needs a ‘King’ is moot, it seems to be getting one, whether it likes it or not. In which case, maybe that King (or future Queen) really does need a castle or administrative centre from which to watch over their lands.

I’m being facetious, of course. But there is one idea that’s been doing the rounds for decades about the governance of the north that never truly goes away, even if no one has quite had the courage to turn it into reality. I’m talking about a Northern Regional Assembly or Parliament – a new constitutional arrangement that would put meat on the bones of devolution. I think it’s worth considering, for two reasons. Firstly, because history teaches us that no matter which party is in power in Westminster, nothing really changes for us. A Northern Regional Assembly would be founded on the simple understanding that only the north can be trusted to look after the north. And the second reason is that, done right, an Assembly could help to counter the divisive politics of regional capitals and agglomeration economics. Power could be distributed in a way that lifts up many communities, rather than few. For this reason an assembly must never be located in Manchester.

‘Let’s aim high. Consign talk of the ‘King of the North’ to the metaphorical dustbin and carve out a new sense of identity and purpose.’

I’ll leave the finer details to minds more attuned to the vagaries of politics and taxation, but it would almost certainly require a bonfire was made of existing local governance arrangements. This would not be yet another fatty layer of bureaucracy feeding off the twitching corpse of local democracy. It would be the pinnacle of a fundamental re-working of power – a place where the core cities and towns of the north would come together to fix and finance their priorities at scale. Cities like Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Newcastle joining forces with the Hull’s, Sunderland’s, Blackpool’s and York’s with one objective in mind – to challenge the economic pull of London and re-position the north as the economic engine room of the UK.

Maybe that sounds fanciful. Can we really reverse the economic gravity of the last 150 years? I don’t know the answer to that but I’d sure like to try. We should have some confidence about what is possible. Most of the UKs core cities reside in the north and our economy is bigger than that of whole countries such as Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, Portugal and Sweden. Our population is made up of 15 million souls and we account for about 20% of the UKs national GDP. While Westminster neglects to address the wealth inequalities that fuelled the demands for Brexit, isn’t it time we took power into our own hands and gave our region a stronger, collective voice? One where different parts of the north were incentivised to put aside regional rivalries and work together.

In which case, I’m going to ask you to imagine a world in which Liverpool becomes the focal point and home of that Northern Assembly. Is that really so far-fetched an idea? Some would immediately dismiss the prospect. Our council is after all essentially under special measures being guided towards competence by government appointed commissioners because we couldn’t manage it ourselves. What credentials do we have? But I’d simply say, why not? We may have had a politically turbulent history and a less than stunning present, but we also have a tradition in the last one hundred years of standing up for the many, not the few. Perhaps there is no more natural home for a regional assembly based on pan-northern equality and fairness as opposed to agglomeration, soft power and resource thirsty regional capitals.

Besides, despite all its issues, Liverpool is a city with an enviable international draw, incredible setting and bags of waterfront space to house such an assembly. A parliament might actually give Liverpool Waters some actual purpose too, while raising our own city’s aspirations. Some of our own will decry it as pie in the sky. But let’s not throw rocks or weave excuses. Let’s aim high. Consign talk of the ‘King of the North’ to the metaphorical dustbin and carve out a new sense of identity and purpose. One that is not only forward looking and aspirational but is also collaborative with its neighbours and based on a desire to see balance, fairness and justice intertwined into the north’s wider politics. it’s already there in the minds and hearts of northern people. Now let’s put it there in the institutions that represent us.

And so in the rest of this article, I’ve taken the liberty of going ahead and designing it. I hope you don’t mind the presumption but they do say a picture is worth a thousand words. I’ve created a series of visuals to conceptualise a new government district centered on Liverpool’s Central Docks.

Assembly District - Principles and Functions

Assembly District fly through.

Today, the site is owned by Peel Holdings and development plans are proceeding at a snail’s pace. A recent consultation was announced for some kind of canalside park, but it’s a blank canvass and no buildings have been announced. The creation of a new political ‘village’ or district laid out to intertwine with neighbouring developments such as Stanley Dock and Ten Streets could be the final piece of the jigsaw for Liverpool’s waterfront regeneration.

This new district would have to accord with some key functional imperatives and some core design principles. For function, the area must be able to accommodate our representatives and supporting administrative staff comfortably and securely. It must capitalise on the economic opportunity by creating desirable workspace which will be attractive to inward investment, and it must be broadly open to the general public to enjoy offering new facilities which are available to all.

From a design perspective, the development should be ambitious and contemporary, forward-looking, sustainable and transparent. This area should boast a ‘postcard design’ while being the embodiment of openness to enshrine in the built form the idea that our representatives work for us, not themselves or even their parties. A trigger for the designs should be northern solidarity. In addition, I’d like to create an element of pleasure through the creation of quality, yet surprising recreational space.

The Ten Streets and Central Docks area today

The Plan

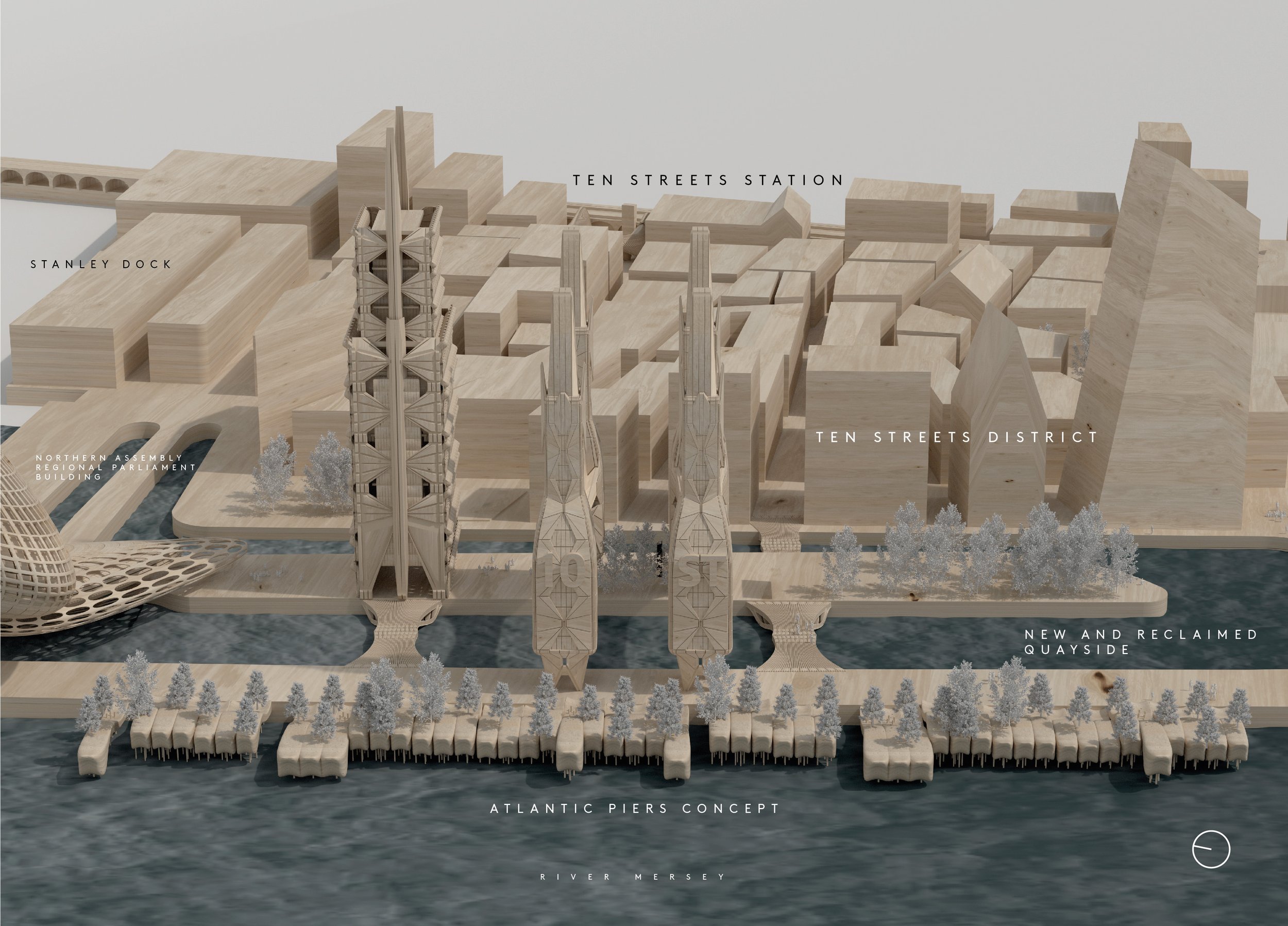

Conceptually, the Central Docks plot would be divided into two areas: river and canal side to the west and further inland to the east. The waterside plots would feature the landmark structures and open space, while the east side could house complimentary mixed-use facilities including both work and residential schemes. Mirroring the adjacent Ten Streets grid pattern, the plans would see a series of new tightly packed, pedestrianised streets opening up the Central Docks site before reaching a series of new waterways and ‘blue spaces’ which will be reclaimed from parts of the site that are currently infilled docks.

New architecture on the site will be encouraged to straddle our quaysides, complimenting and working with water space rather than requiring for it to be filled in to create room for building. This in meant as both a symbolic and practical gesture of compromise in a city often at loggerheads with itself on how to reach for the stars architecturally without compromising existing heritage.

The centre piece of this new district would be the Northern Assembly building. Built across a series of pillars and positioned across the quayside to create a floating form, the building would be in a perfect position for security being largely surrounded by water and accessed only from one side. As a landmark for the north of England, the assembly would feature a circular internal layout to encourage parliamentarians to work together as one collective, while ensuring all areas of the north where represented equally. Cladded in steel and glass, with an undulating façade, the building would take some inspiration from Germany’s Reichstag building in which the public are free to observe parliamentary sessions as part of a commitment to transparency.

On the riverside of the Assembly building, a new public space would be built on a series of interconnected concrete pier structures inspired by Heatherwick Studio’s ground-breaking and beautiful Little Island Park in New York. Each of the up to 50 piers would represent core towns and cities as part of a linear park space on the water’s edge topped with attractive landscaping and robust Mersey-friendly planting. The piers are also symbolic of Liverpool’s position as an arrival and departure point for the whole of the north of England. Together with green spaces throughout the site, reclaimed and newly created blue space and interconnecting bridges this area would become a landmark open space for the city, a riverside space to think, debate, contemplate and engage with politics in a new heart of central Liverpool.

Two other landmark buildings neighbouring the Assembly are proposed for the water-side plot – one striking, multi-use cultural building and one mixed use 35-storey office and hotel.

The office and hotel building has been given a classic robot form with square body, head and antennae – this slightly retro but nevertheless futuristic form pointing to the need to put the industries of tomorrow at the heart of the north's strategy.

The form of the cultural building, which could house museums, exhibitions, performance and meeting spaces as well as a visitors centre, is modelled on a modern interpretation of Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral while it’s four brick turrets are an echo of the city’s landmark Liver Building. The overall effect is somewhat church-like to reflect the central role that faith and secular belief and moral values have in our communities and their deep historical roots in the region.

Transport

One of the key issues facing Liverpool’s central and north docks area is that of connectivity. To compare Central Docks to waterside redevelopment plots in London’s Battersea and Docklands areas it’s clear that a development of this scale and footfall would require a comprehensive transport strategy.

Conceptual design for Ten Streets station, Northern Line.

One possible solution would be the development of a station on the Merseyrail Northern Line to the western edge of the site. Built across existing railway viaducts and positioned equidistant between Moorfields and Sandhills. This new station could multiple audiences including the emerging creative Ten Streets district, Assembly District and also Everton’s Bramley Moore Stadium a few hundred yards north.

One of the key factors slowing down the regeneration of the north Liverpool docks has been access to the city centre and transport in general. Whilst a station at Ten Streets would go a long way to addressing this problem, the influx of new high density development may increase the viability of further transport infrastructure. The plans to the east of Central Docks envisage a concentration of high density homes and commercial and administrative buildings. The substantially increased footfall and employment in the area could support the creation of a new light rail link connecting directly with Lime St station through the currently disused Waterloo/Victoria tunnel alignment.

For illustrative purposes and to create a sense of arrival at the new Ten Streets station, I am proposing two wing-like structures addressing a new public square. Essentially abstract in form, they provide a modern interpretation of the industrial cranes that would once have been seen in the area. They also serve an important function, providing weather-proof covering for 4 escalators which take passengers up to the station’s platform level.

The Northern Assembly is the first of a two part article exploring the development of the Central Docks area. For our next article I will be exploring how the Ten Streets district itself could take advantage of Liverpool’s digital and gaming sector and if extended pull the area closer to the city centre.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Liverpool Waters: Peel’s recipe for anytown, anywhere

The debates around development at Waterloo Dock and the expansion of John Lennon Airport were of totemic significance to the city of Liverpool revealing a schism between competing visions of our future. Progress and ambition pitted against tradition and conservation or so we are led to believe. But as Jon Egan argues, in the first of our new Debating Our Future series, there may be a third way.

Jon Egan

The debates around the Waterloo Dock project in Liverpool Waters and the expansion of Liverpool Airport caused heated debate amongst Liverpolitan’s contributors leaving plenty of room for disagreement. But one thing we all agreed on was their totemic importance to the city, revealing a schism between competing visions of our future. It’s a discussion the people of Liverpool need to have. What kind of place do we want to be? In this article, Jon Egan self-identifies with those sometimes christened as ‘nimbys’ and puts forward his idea for a city built around the cultivation of difference, individuality and beauty.

In the months ahead, we’ll explore these issues from other perspectives as part of a new ‘Debating Our Future’ series. If you would like to contribute to the discussion with your own vision, contact team@liverpolitan.co.uk

It's rare we embark on journeys in pursuit of the familiar, the ordinary or the humdrum. Travel, they say, is about broadening the mind, experiencing new sights, sounds, flavour and ambiences. The places we cherish and remember are those most imbued with a capacity to charm and surprise. So for places and cities aspiring to become destinations, cultivating and conserving what makes them different and original seems like a rewarding strategy. For Liverpool, a city that loudly proclaims its originality and inimitability, this should be a simple and unchallenging task.

When travel is neither practical or affordable, we always have the consolation of reading about the places we yearn to visit, experiencing their enchantment vicariously, though often with the added patina of poetic imagination.

Italo Calvino’s 1972 novel, Invisible Cities, is predicated on a series of imaginary conversations between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan. The famed traveller regales the Mongol Emperor with tales of the many fabulous cities he has visited, but true to the spirit of Calvino’s magical realism, these are not actual cities, nor even possible cities. They are extraordinary and fantastical creations - parables and paradoxes that explore what the book describes as the “exceptions, exclusions, incongruities and contradictions” that characterise and differentiate cities. Towards the end of the book, Marco Polo describes a city that heralds a disturbing vision, an incipient possibility foreshadowing the endpoint of globalisation.

“If on arriving at Trude I had not read the city’s name written in big letters, I would have thought I was landing at the same airport from which I had taken off. The suburbs they drove me through were no different to the others with the same little greenish and yellowish houses. Why come to Trude? I asked myself, and I already wanted to leave. “You can resume your flight whenever you like”, they said to me, “but you will arrive at another Trude, absolutely the same detail by detail. The world is covered by a sole Trude which does not begin and does not end. Only the name of the airport is different.”

The Waterloo Dock project in Liverpool Waters has totemic significance. For modernists it stands for ambition, progress and status. For the conservation lobby it was loaded with deep symbolism representing the destruction and the desecration of heritage.

So what, you may ask, does this have to do with Liverpool and its future? The answer lurks somewhere in the subtext of a recent planning controversy that divided commentators and communities, polemicists and politicians.

The project was the proposed residential development on the partially infilled Waterloo Dock in Peel’s Liverpool Waters. For modernists and urbanist thought leaders the project had totemic significance, standing as a shorthand statement of ambition, progress and status. For the conservation/heritage lobby the project was similarly loaded with deep symbolism representing the destruction and the desecration of heritage. The fractious debates and the absence of a shared narrative or vocabulary suggest a city without a clear or shared sense of self, insecure about its past and uncertain about its future.

The Romal Capital proposals for Waterloo Dock in Liverpool Waters were unanimously rejected by the Liverpool City Council Planning Committee on 18th Jan 2022. The developers have appealed and the plans will now go before the government’s Planning Inspectorate

So which side am I on? Typically perhaps for a Libra, both and neither. I have lamented the city’s lack of ambition, absence of vision and its inability to answer, or even ask itself, the fundamental question - what is Liverpool for? But I have also questioned the assertion implied, or explicitly asserted by some, that development is nearly always an intrinsic good. Indeed, in the context of the Waterloo Dock debate, I found myself aligned with alleged nimbys, and in spirited disagreement with many allies including the Editor and Founders of this publication.

Maybe the partial infilling of the dock and construction of an inoffensively bland apartment building was not the greatest ever crime against Liverpool’s heritage, but neither was this drably functional box of micro-apartments the most aesthetically or socially desirable addition to our (formerly) World Heritage waterfront. The debate and passions were evidently focused on bigger agendas and deeper sensibilities.

Fly-through video panorama of Waterloo Dock, Liverpool filmed in January 2022

Looming almost literally over the Waterloo Dock debate is a bigger picture, a grander vision and a development proposition that has insinuated itself into being a substitute for an actual future vision for our city. Liverpool Waters is now so ingrained into the city’s discourse and psychogeography that you could be forgiven for thinking that it actually exists. Peel’s near messianic promise to deliver Manhattan or Shanghai on the Mersey was proclaimed with a prophetic urgency in 2007, imbuing its curiously cinematic CGI’s with a hyperreal potency. When choosing between the actuality of World Heritage Site designation and the ephemeral fool’s gold promise of Liverpool Waters, we opted for the phantasy.

Liverpool Waters has both framed and constrained the debate about what sort of city we want to be, and what kind and quality of development we should be encouraging and embracing. Tall buildings have an obvious glamour. UK cities in particular seemed to be in frenzied competition to erect the tallest buildings, as if this, above all else, was a shortcut to status and significance.

Peel’s phalanx of waterfront skyscrapers was Liverpool’s trump card ready to be played (at some ceaselessly rolling future 30-year date), catapulting us ahead of our provincial rivals and reasserting our true global status. But is this what we want for Liverpool - a derivative identity, a replicant city? Trude on the Mersey?

Without for one second surrendering to nimbyism, we can recognise that imitation and simulation should not be our template. Echoing Calvino’s prescient warnings about globalisation, Desmond Fennell, the essayist and philosophical writer, foresaw similar tendencies at work in the early days of Ireland’s embrace of cosmopolitan modernity. In a beautifully evocative passage, in his book, State of The Nation, Fennell laments the loss of Dublin’s once rich and distinctive urban culture and soul. He mourns the curious and idiosyncratic details and delights that once defined and differentiated places.

Liverpool Waters is now so ingrained in the city’s discourse and psychogeography that you could be forgiven for thinking that it actually exists.

“If he is a Dubliner, walking amongst the offensive tower blocks, one who can cast his mind back 20 years, he will remember the vast Theatre Royal with its troupe of dancing girls, The Capitol and the old Metropole with their tearooms, Jammet restaurant and the back-bar, the incomparable Russell, the Dolphin, Bewley's and the Bailey as they used to be, the elegant grocers shops staffed by professionals of the trade, the specialist tobacconists with their priest-like attendants... It would be an exaggeration to say that consumerism destroyed or reduced the quality of everything: it improved the quality of tape-recorders, computers and inter-continental missiles and many other things. But it destroyed many of the amenities and much of the pleasure of cities, and, in a sense, the city as such."

The steady erosion of difference, character and defining originality is in danger of creating a sense of alienation and disinheritance as places converge and identities become eerily homogenous. We lose our bearings as familiar places lose their landmarks and legibility.

All too often progressives and modernisers have a tendency to disparage ‘conservatives’ whether they are rabid xenophobes or harmless nimbys, as people living in the past, fearful of change, trapped by prejudice and insecurity. But sometimes those who question change do have a point, even if it escapes rational or tangible articulation. Loss is something that is easier to feel than it is to explain.

So am I proposing a future constrained by conservation and suffocated by the cult of heritage? The simple answer is no, and if I may be excused for recycling New Labour nomenclature, I believe there is a third way. It’s an approach that can be radical, imaginative and ambitious without being imitative or simulatory. In a recent Guardian Op Ed, Simon Jenkins added his voice to the argument for diverse and differentiated strategies for regeneration.

“The Leaders of Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham and Bristol can think of no other way of competing with London than by erecting garish towers of luxury flats in their central areas. They ignore the evidence that modern creative clusters - in design, marketing, the arts and entertainment - are drawn to historic neighbourhoods and old converted buildings… Northern cities regard their Victorian heritage as a liability not an asset.”

For Liverpool this should not mean a moratorium on tall buildings or intelligent contemporary design, but it should be a challenge to rethink and re-prioritise. We know from our experience that innovation and regeneration are about more than large-scale physical development and shiny glass towers. It’s about what happens in the cracks and gaps, the higgledy-piggledy neighbourhoods and Wabi sabi spaces where innovators and pioneers just get on with it. So let’s learn the lesson from the Baltic and formulate a planning framework for the Fabric District before its character and urban ambience are swamped by more identikit apartment blocks.

The decline of our port economy has bequeathed us an enviable array of empty buildings and fallow dockland areas ripe for reseeding as creative clusters. But areas like Ten Streets need more than protective planning frameworks, they need assertive interventions and clever curation if they are to fulfill their potential. Where are the big catalytic ideas that would stimulate investment and clustering in an area that may otherwise remain a squandered asset? If we see Ten Streets as the incubator for a world-class digital cluster, should it also be the home for Liverpool’s equivalent of Paris’ Ecole 42 - the digital “university without teachers” whose model and approach is now being embraced by cities ambitious to expand their technology and creative sectors.

And what about Ten Street’s brash and status-obsessed neighbour? It’s time to radically reappraise Liverpool Waters. As a benchmark for ambition it’s looking increasingly hackneyed, irrelevant and unrealistic. Even its most impassioned advocates are now beginning to question whether Peel is seriously committed to actualising this Fata Morgana version of Liverpool's future.

The debate about the northern docks should not be a battleground between nimbys and tall building fetishists. It should be about what the city needs and how the immense potential of vacant dockland can be harnessed to make Liverpool a different and more attractive city for its people, its visitors and investors. In San Francisco the development brief for its historic piers (former docks) proposes a mid-rise human scale built form aimed at preserving the setting of the city’s downtown cluster - an important part of its visual signature - but also to safeguard the city's view of the bay and sense of connection to its port history. Far from fostering mediocrity, the city has encouraged architectural excellence and experimentation with brilliantly innovative contributions from Thomas Heatherwick amongst others. Ironically, this was the approach favoured by UNESCO as the basis for the future evolution of our World Heritage Site. It’s also an approach that would have facilitated a more seamless integration with Ten Streets and wider North Liverpool.

Sometimes those who question change do have a point, even if it escapes rational or tangible articulation. Loss is something that is easier to feel than it is to explain.

Of course, we need to recognise that regeneration of the city centre alone will never suffice; Liverpool’s individual identity resides as much in its suburbs and neighbourhood high streets, its stunning parks and rich Georgian and Victorian legacy as it does in the more showpiece locations. Prefiguring Calvino's parable, Marxist critic Guy Debord and his Situationist collaborators warned that the redevelopment of Paris in the late 1950s signified a ruthless process of rationalisation, commercialisation and homogenisation where the authentic social life of cities was being replaced by spectacle - "all that was directly lived has become mere representation." Like their Surrealist forbears, the Situationists saw the city as a playground or dramatic stage promising limitless encounters with the extraordinary and the unexpected (le merveilleux quotidien).

It seems strangely apposite for a city seduced by the film-set flimsiness of Peel's promise, that we cherish our architectural heritage less for its intrinsic quality - its lived experience - than its capacity to mimic more significant and glamorous places. Sure, we can take pride in being the UK’s most filmed city, but is that it? Is our identity founded on an aptitude for imitation and representation?

Peel's penchant for visionary masterplans extends beyond the stalled blueprint for Liverpool Waters. Equally "ambitious and aspirational" are its plans to transform our humble provincial airport into a global hub with direct links to long haul destinations on every continent. Irrespective of the merits, feasibility or environmental impact of the plan, it is another ingenious attempt to stroke the ego of a city short on self-belief and uncertain about its place in the world.

Proper cities have proper airports, and the fact that Manchester has one, is less a matter of convenience than cause for a deep seated inferiority complex. But as latter day Marco Polo, Bill Bryson’s descriptions of Manchester as “an airport with a city attached” and “a huddle of glassy modern buildings and executive flats in the middle of a vast urban nowhere,” reveal, mere status symbols are not enough to make a city significant or memorable. In contrast, Bryson observes that “in Liverpool, you know you are some place.”

We need a regeneration prospectus based on the cultivation of difference and individuality, that cherishes what’s unique, irreplaceable and above all beautiful, but also fosters experimentation and originality. We want Liverpool to be the conspicuous and refreshing antidote to the nightmare of endless and interchangeable Trudes.

Being “some place” is not a bad guiding principle for a city seeking to nurture difference, and be a place that people want to come to, and are in no hurry to leave.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.