Recent features

HS2 Cuts: A Second Chance for Liverpool

As we wave goodbye to any ideas of HS2 reaching the north, a deafening chorus of betrayal is drowning out attempts to assess the project’s worth more rationally. Yet the inconvenient truth is that many in the north have never been convinced of the value of HS2. In this article, Martin Sloman, a director at influential lobby group, 20 Miles More, asks whether the HS2 re-set is a golden opportunity for Liverpool - a second chance at creating new transport infrastructure that works for our city?

Martin Sloman

As we wave goodbye (at least for now) to any ideas of HS2 reaching the north, a deafening chorus of betrayal is drowning out attempts to assess the project’s worth more rationally. Yet for all that, there is an inconvenient truth displayed every time a BBC journalist puts a microphone in front of the general public - the existence of a clear disconnect between the project’s advocates and your average paying train passenger. Lord Adonis may cry foul but many in the north have never been convinced of the value of HS2. In this article, Martin Sloman, a director at influential lobby group, 20 Miles More, considers the matter from Liverpool’s perspective. He asks the question, is the HS2 re-set a golden opportunity - a second chance at creating new transport infrastructure that works for our city?

And so there it is. HS2 beyond Birmingham has gone the way of the Dodo. It is no more. It has ceased to be. It is an ex-railway.

Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak’s much trailed announcement at the Conservative Party Conference to hack back the UK’s largest public transport project represents not just a big throw of the political dice, but a huge scaling back of HS2’s ambitions. Unless you believe a Starmer-led Labour government will revive the scheme (don’t bank on it), the line will no longer extend to Manchester, instead terminating at Birmingham, the place that likes to call itself ‘the second city’. Brum’s claims have been bolstered now. This news is seen almost universally amongst the commentariat as a body blow to the much-vaunted ‘Levelling Up’ strategy, but what does it mean for Liverpool and our city region? Should we see it less as a disaster for the north and more as a second chance to get our city’s transport infrastructure right?

Liverpool came late to the HS2 debate. It was only after the Phase 2 proposal was revealed in January 2013 that we began to realise how the project would affect us. By then, the route was set in stone, and it didn’t look good. The new line was designed as if Liverpool didn’t exist. There would be stations at Manchester Piccadilly and Manchester Airport, a lengthy tunnel into Manchester city centre and a link to the north via Wigan. Liverpool would be lucky to get new, plastic platform seating.

Under the HS2 plan, its high speed trains would run from Liverpool to London but would first need to traverse almost 40 miles of Victorian railways at slower speeds before accessing new, gleaming track south of Crewe. The Liverpool service would be limited to the shorter 200m ‘classic compatible’ trains with half the seats and would run two services per hour with a running time to London of one hour and 34 minutes. Meanwhile, Manchester would receive the gold-plated service - three 400m double-length ‘captive’ trains per hour, speeding to the capital in one hour and 8 minutes – three times Liverpool’s capacity and 28% faster – the end of historic parity in connections to the south.

The lack of high-speed infrastructure to serve Liverpool would prevent the release of capacity on our existing local network, which was supposed to be one of the selling points of HS2. This would severely limit the development of new passenger and freight services and ran contrary to the recommendations of ‘Rebalancing Britain: Policy or Slogan?’ – the Heseltine / Leahy report of 2011 which stated:

‘Government should amend the currently proposed High Speed 2 route, so it connects to both Manchester and Liverpool directly. In the same time frame and to the same standard, Government should commit to assuring Liverpool’s historic parity with Manchester for travel time to London and thereby avoid harmful competitive disadvantage to Liverpool in attracting inward investment’.

That harmful competitive disadvantage was confirmed by accounting giants KPMG who produced their report – HS2 Regional Economic Impacts on behalf of HS2 in 2013. It showed maps of Britain covered in big green circles, where HS2 would uplift the economy of cities and towns. There were, however, little red circles and they were less good news and one of them was over Liverpool. To be fair, the report claimed Liverpool’s GDP could be uplifted by 1.2% in ‘favourable’ conditions, but equally it could shrink by 0.5% in ‘unfavourable’ ones. Not exactly a ringing endorsement and a worse outcome than for towns and cities that were not even connected to the network in any way, such as Hull.

In response to this threat, a coalition of academics and local business figures led by Andrew Morris banded together to form 20 Miles More, an independent campaign group lobbying for a direct, dedicated link to HS2. The 20 miles referenced in the name referred to the length of the shortest link to the HS2 network. Our group, of which I was a director, produced reports, met with political, business and transport leaders and responded to consultations. The assistance of political consultants Jon Egan and Phillip Blond helped us to secure television coverage for our launch event.

Something must have stirred because not long after the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority and the local councils woke up to the danger and launched their own campaign called Linking Liverpool and we’d like to think we had something to do with that. They calculated that a direct Liverpool link to HS2 would be worth £15 billion to the local economy and secure 20,000 new jobs. At last, the issue facing our city was being taken seriously.

“That harmful competitive disadvantage was confirmed by accounting giants KPMG. Their report showed maps of Britain covered in big green circles, where HS2 would uplift the economy of cities and towns. There were, however, little red circles and they were less good news and one of them was over Liverpool.”

One point that we made in our report was that a Liverpool link to HS2 could form part of a new rail link to Manchester and over the Pennines to Leeds. We felt vindicated when the Northern Powerhouse Rail initiative was launched in 2014. This envisaged six northern cities – Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Hull, Sheffield and Newcastle being linked by new high speed rail infrastructure. This resonated with Boris Johnson’s ‘Levelling up’ agenda.

In 2020, construction work on the first phase of HS2 (London to Birmingham) started and the realities began to strike home. The prospect of miles of countryside being torn up for a new railway generated local opposition and the wrath of environmental groups, especially in the home counties, but it was the rapidly escalating cost of the project that really concentrated minds. An initial 2010 estimate of £33 billion had now ballooned to £71 billion with some commentators suggesting the final figure could be well over £100 billion.

Why costs spiralled out of control may be down to a number of reasons – overspecification of the initial project, inflation, procurement issues, planning delays, environmental mitigation, and of course, government interference. The result was cutbacks and delays, culminating in Rishi Sunak’s announcement at the Tory’s Manchester Conference – bad news for ‘the north’ delivered in the self-declared heart of ‘the north’, eyeball to eyeball.

Figure 1

Routes and phasing of HS2 as they stand following Sunak’s recent announcement.

Looking at the map, what Sunak has done is to prune HS2 back to Phase 1, which runs from London to Birmingham. Gone is Phase 2a from Birmingham to Crewe, Phase 2b (East) from Birmingham to East Midlands Parkway and Phase 2b (West) from Crewe to Manchester. What has been retained is the link from London Euston to Old Oak Common (reportedly now subject to finding private sector investment) – vital for delivering an effective HS2 service – as well as the link at Lichfield (Handsacre) junction to the existing West Coast Main Line, which allows trains from Liverpool and Manchester to make use of HS2.

The implications for the North West are significant and on the upside, the damaging inequality between Liverpool and Manchester identified by Heseltine and Leahy has been removed. So, from the completion of Phase One (currently scheduled for some time between 2029 and 2033), both Liverpool and Manchester will have services to London making use of existing tracks as far as Lichfield. Trains will run on HS2 for over 60% of the distance from London to the North West with the remainder of the journey on the much slower classic network. That will give a journey time to Liverpool of around one hour and 46 minutes and to Manchester of one hour and 41 minutes. This five-minute difference contrasts with the 26-minute difference that would have occurred had Phase 2b gone ahead. Liverpool’s train capacity will be unaffected, remaining at two 200m long units per hour (each carrying up to 550 passengers) - whereas Manchester will see a halving of its promised capacity to three 200m units. This is because the 400m long, 1100 passenger ‘captive’ trains (trains that can only run on the new HS2 route) that were to serve Manchester under the original plans can no longer do so.

“It is difficult to support a proposal that would deliver so little to our city and so much to a city that is an economic rival.”

The reduction in overall train capacity and increase in journey time is, of course, a body blow to the North West and has resulted in accusations of betrayal in certain quarters. But while the avoidance of baked-in disadvantage between our two cities might provoke a sigh of relief in some, it would be wrong to assume that what is bad for Manchester must be good for Liverpool. As Jon Egan pointed out in his recent Liverpolitan article, Mancpool: One Mayor, One Authority, One Vision, the real disparity is not so much between Liverpool and Manchester but between the two cities and London. However, it is difficult to support a proposal that would deliver so little to our city and so much to a city that is an economic rival.

Rethinking Northern Powerhouse Rail

Another victim of the latest cuts is Northern Powerhouse Rail. This body is to be replaced by a new entity known as Network North and improved journey times are promised from Manchester to Bradford, Sheffield and Hull with £12 billion allocated to a link between Manchester and Liverpool. How that money is to be spent will be the subject of agreement between our civic leaders (and presumably other North West towns such as Warrington).

Northern Powerhouse Rail envisaged high speed lines linking the main cities of the North West. However, when the Department of Transport published the Integrated Rail Plan (IRP) in 2021, these aspirations were somewhat diluted.

Figure 2:

The Integrated Rail Plan (2021) - not so integrated now

“What does all this mean for that ring-fenced £12bn route between Liverpool and Manchester? Will there still be a requirement for the Manchester Airport tunnel? Budgeted around the £5bn mark (before inflation hit) that would take a hefty chunk out of the available cash.”

According to the IRP plan, the Liverpool to Manchester rail route would be achieved by a mixture of upgraded freight and passenger lines, some new construction and the Manchester branch of HS2.

This arrangement was never optimum – being seen as a ‘bolt-on extra’ to HS2. However, it did directly connect Liverpool to the new rail network allowing a London connection to HS2 via Tatton Junction.

Changes were made to the IRP routing following the publication of Sir Peter Hendy’s Union Connectivity Review in November 2021. Hendy identified that the best way of increasing passenger and freight capacity to Scotland and Northern Ireland (via the Port of Liverpool) was by upgrading the existing West Coast Main Line north of Crewe.

The proposed route of HS2 to the North – the ‘Golborne Spur’ to the east of Warrington - was subsequently deleted and a review put in place to determine an alternative route that better met the aspirations of the Hendy report. This is, for now, clearly off the agenda.

So, what does all this mean for that ring-fenced £12bn route between our cities? Will it stay the same or once again morph into something else? Certainly, this is an opportunity to completely rethink the Liverpool to Manchester link. For example, will there still be a requirement for the Manchester Airport tunnel? If so, budgeted around the £5bn mark (before inflation hit) that would take a hefty chunk out of the available cash – although it is difficult to see how else a new link can be run into central Manchester. However, given that there is no longer a need to accommodate HS2, strictly speaking there’s no reason why an improved alignment can’t be sought. But there may be other ways to spend the money.

A Mersey Crossrail?

Prime Minister Sunak has promised that the £36 billion ‘saved’ by the cancellation of HS2 Phase 2 will be re-invested in a plethora of new transport projects. Mention has been made of electrifying the North Wales main line, extending the Midland Metro, a host of road projects and finally giving Leeds its long-promised metro. Given that the cancellation means that we in Liverpool will now suffer from reduced journey time to the capital, let’s hope that a reasonable slice of that money comes to our city.

Liverpool has a developed transport network thanks to the infrastructure work of the 1970s, which gave us the Merseyrail system. However, one problem with the network is its limited coverage. The frequent electric trains running underground in the city centre only serve the Wirral, Sefton, a narrow strip of north, south and central Liverpool (but not the east) and a small part of Knowsley. That is a result of a failure to complete the original project following funding constraints in the mid-70s.

Now, we have the chance to complete that project – something that would give the Liverpool City Region a comprehensive rapid transit system second to none in the UK outside the capital.

I’m going to call it Mersey Crossrail because it would truly open up transit from north to south and east to west. It would make possible near seamless travel not only within Liverpool but also to the important network of satellite towns around and beyond the city region. The access to new job and lifestyle opportunities that would arise would be transformative for our people, while also encouraging modal shift to greener forms of transport. How much would this work cost? Probably in the region of £1 billion, which is a fraction of the cost of constructing a similar system in another city. That is because so much of the system is already in place.

So, what would this project entail? Apologies in advance because I’m now going to get into the nuts and bolts. I can’t help myself, I’m a rail enthusiast.

“Mersey Crossrail would make possible near seamless travel not only within Liverpool but also to the important network of satellite towns around and beyond the city region.”

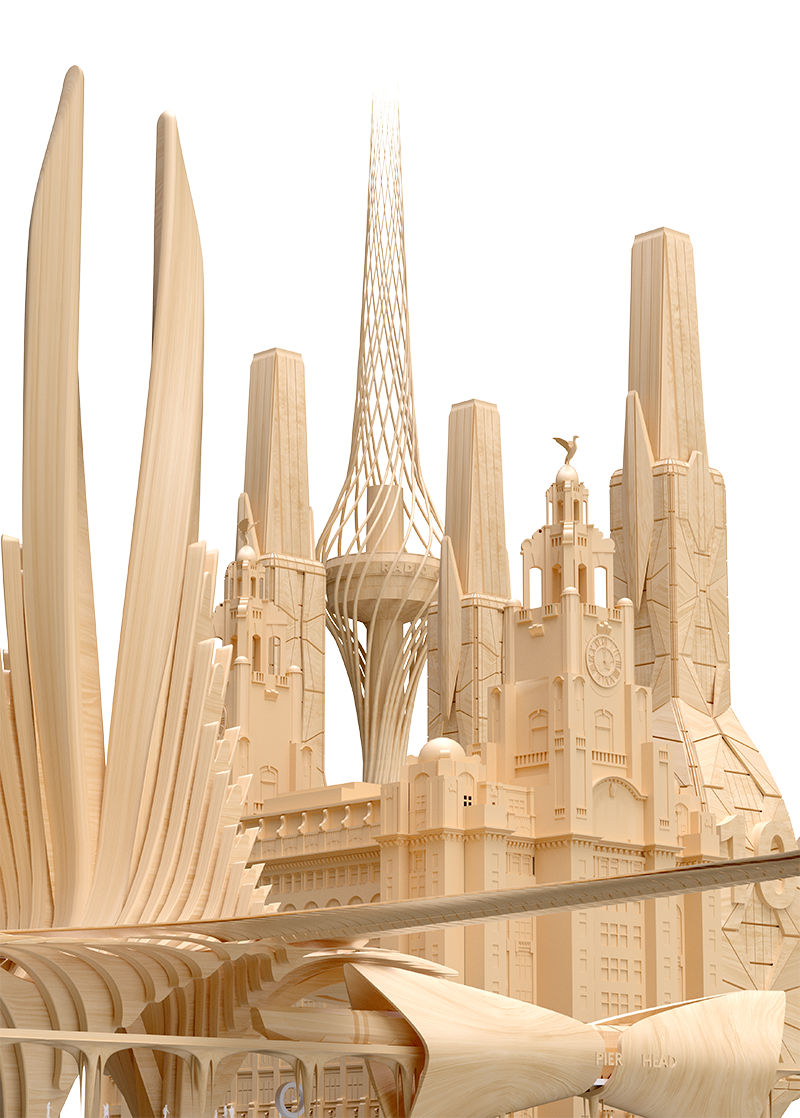

Imagined, new Liverpool Central Station at the heart of an expanded Merseyrail network. Images by: mmcdstudio.

A 4-Step Transport Plan for Liverpool - Features and Benefits

Step 1. Expand Liverpool Central Station

First up, an expansion of Liverpool Central station, which currently hosts Northern Line services to Southport, Ormskirk, Kirkby and Hunts Cross. The station suffers from overcrowding due to its cramped island platform and the need for enlargement has long been recognised.. Widening the station envelope would not only improve the passenger experience, it would also unlock the next stage of transport expansion.

Step 2. Unlock the network by building the ‘Edge Hill Spur’

A new tunnel would be constructed from the south end of the station to Edge Hill connecting to the disused Wapping Tunnel which dates from the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway in 1830. This proposal was formerly known as ‘The Edge Hill Spur’ and is the key to unlocking the true potential of the Merseyrail network because trains would now be able to run seamlessly east to west underneath the city streets in part by using old, mothballed underground tunnels. This Edge Hill link would effectively form a Mersey Crossrail with the prospect of services running between towns such as St Helens and West Kirby. Construction would involve minimal disruption to existing services thanks to header tunnels constructed back in the ‘70s.

The benefits of such a scheme are immense. Merseyrail would be cheaper to run because transiting through the city instead of terminating makes more economical use of trains and train crews, potentially increasing train frequency. However, it’s the expanded travel opportunities that would be the major plus.

Every station on Merseyrail would be within a maximum of one change of every other one. For example, City Line passengers would have direct access to Liverpool Central and Moorfields with their retail and employment opportunities or could run through to other destinations such as Birkenhead, Chester, Bootle or Southport.

“Every station on Merseyrail would be within a maximum of one change of every other one.”

Step 3. A new underground station for the Knowledge Quarter

One proposal that’s never made it off the drawing board is an underground station near to the university on Catherine Street serving the Hope / Myrtle Street area. Build the Mersey Crossrail and this could become a realistic option, not only adding important services for our legion of students and academics but also a much-needed shot in the arm for the broader Knowledge Quarter, including the strategically important Paddington Village area with its growing medical biotech cluster.

Step 4. Create new Merseyrail branches to the wider city region and beyond

With the partial reconstruction of a former flyover at Edge Hill, City Line services could link Runcorn to St Helens and Newton-le-Willows. This would add three more branches to the Merseyrail network covering a broader sweep of Liverpool, Knowsley, St Helens and Halton. Services could even be extended beyond the City Region boundary to Wigan, Manchester and Crewe thanks to the Northern Hub electrification schemes of the last decade and the introduction of the new fleet of Merseyrail trains with their dual voltage capability.

Another opportunity, which is already in progress, and which would benefit from additional funding, is the extension of the existing Merseyrail network using battery technology. We can now see this technology in operation with the opening of the new Kirkby Headbolt Lane station. This is served by trains running off the electrified network from the existing terminus at Kirkby. Future proposed destinations include Preston via Ormskirk, Warrington Bank Quay via Helsby, Wigan Walgate via Kirkby and, possibly the complete length of the ‘Borderlands’ Line from Bidston as far as Wrexham.

One great benefit of battery extensions, apart from avoiding the cost of extending electrification, is the opportunity to displace existing diesel services (e.g. Kirkby to Wigan, Ormskirk to Preston), so both reducing operating costs and harmful emissions.

Figure 3:

Shows the Merseyrail extensions possible with the Mersey Crossrail scheme. It also shows the existing proposals for battery extensions of the existing Wirral and Northern Lines.

With all of the proposed extensions in place, Merseyrail would become a powerful regional rail network, fully integrated into Liverpool City Centre. It would extend both into North East Wales and Greater Manchester.

It should be noted that, these extensions reflect the level of spending on transport expected for a city region the size of Liverpool, with a population of 1.5 million people. It is by no means extravagant.

The cancellation of Phase 2 of HS2 has been a blow for the North West region. However, the Liverpool City Region missed out on the initial proposals. Now, there is an excellent chance to redraw the rail map of the North West to give a more equitable distribution of the benefits that will still flow from the Phase 1 railway.

We now have a second chance with everything to play for. So, let’s hope that our political leaders take notice and deliver us the transport system that the region so clearly requires.

Martin Sloman is a civil engineer and former railway consultant. He is a director of the ‘20 Miles More’ lobby group, a coalition of academics and local business figures, which campaigned for a direct link from Liverpool to HS2.

What do you think? Let us know.

Add a comment below, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Mancpool: One Mayor, One Authority, One Vision?

Should the city of Liverpool throw in its lot with Manchester and accept one combined North West Metro Mayor to rule us all? Despite admitting that such a suggestion is about as saleable as a One State Solution for Israel-Palestine, Jon Egan thinks it’s an idea whose time has come. It’s certainly an idea that’s provoked some debate within Liverpolitan Towers. But what do you think?

Jon Egan

Manchester Bees Meet Liverpool Super Lambananas by mmcd studio

Is it time the city of Liverpool threw its lot in with Manchester and accepted one combined North West Metro Mayor to rule us all? Jon Egan thinks so. As you can imagine, the suggestion has caused some debate in Liverpolitan Towers and we are not all in agreement. But what do you think? Here Jon makes his case and hints at future initiatives to come…

So let me issue a warning now. This article contains material that many Liverpudlians will find deeply distressing and offensive. It’s an argument that I have tentatively proffered in the past, but after profound and serious reflection, have concluded, now needs to be set out in the most explicit and uncompromising of terms. You have been warned.

David Lloyd’s recent article for The Post lamenting the exodus of Liverpool’s “best and brightest” was as ever an enlightening and enjoyable read, notwithstanding its downbeat and dispiriting narrative of civic and economic decline. If I can add a generational postscript in support of David’s thesis, every member of our youngest daughter’s friendship group from Bluecoat School now lives and works outside Liverpool.

It was the nineteenth century philosopher, Friedrich Nietzche who argued that only as an “aesthetic phenomenon” does the tragedy of human existence find its eternal justification, and perhaps it’s only in the exquisite prose and imaginative virtuosity of David’s writing that Liverpool’s own tragic predicament becomes philosophically palatable. I admire David’s resolute determination to find some tiny component of hope, offered in the city’s joyously ephemeral hosting of Eurovision 2023. But does our capacity for celebration, hospitality and togetherness provide the alchemy for a viable economic renaissance? Does it, at best, illuminate Liverpool’s status as a half-city, stripped of its economic and productive assets, now reduced to the sheer potentiality of its human capital?

The idea of Liverpool as a stage set for cultural spectacles and entertainment extravaganzas (hyperbolically described by the city’s cultural supremo, Claire McColgan as “moments of absolute global significance”), is a beguiling substitute for an actual economy, and an ability to offer a livelihood for the generations who continue to depart for more attractive and seemingly successful cities. It’s a vision that also reminds me of another of Italo Calvino’s magical realist parables in his masterpiece novel, Invisible Cities. Sophronia, the half-city of roller-coasters, carousels, Ferris wheels and big tops, where it is the banks, factories, ministries and docks that are dismantled, loaded onto trailers and taken away to their next travelling destination.

“I fully grasp the deeply heretical nature of this proposition. A ‘One State’ solution for the Liverpool and Manchester City Regions is about as saleable as a one state solution for Israel and Palestine.”

Two hundred years ago, the realisation that we were a half-city inspired Liverpool’s city fathers to contemplate a project that would have world-changing implications - a genuine moment of “absolute global significance”. Prior to the construction of the world’s first inter-city railway, every human journey between major population centres would be dependent on the locomotive capabilities of the horse. Railways were the harbingers of modernity, compressing time and space, and in this instance, connecting one of the world’s great trading centres with its greatest manufacturing hub. Umbilically conjoined, the two half-cities (the place that trades and the place that makes), became the nexus for Britain’s industrial and imperial prowess for the next hundred years.

If the railway brought Liverpool and Manchester closer together, recent decades have been dominated by a football-terrace inspired antagonism aimed at driving us further apart. Liverpool’s antipathy to our more affluent neighbour would seem also to betray more than a slight hint of jealousy, as our rival has greedily accumulated the trappings and status of regional capital.

Rather than resenting Manchester’s success or investing in a strategy of do-or-die competition, is there a smarter and mutually beneficial alternative? Is it time to re-imagine a more symbiotic relationship, that realises that for every British provincial city, the real competition is located 200 miles to the south?

Of course, this is not an original proposition. In the early noughties, Liverpool Leader, Mike Storey and his Manchester counterpart, Richard Leese signed their much lauded Joint Concordat - an agreement only marginally less shocking than the Molotov-Ribbentrop ‘Non-Aggression’ Pact of 1939 between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The benefits were equally short lived. The agreement was conceived in the golden age of regionalism when under the aegis of John Prescott’s mega-ministry - the Department for the Environment, Transport and the Regions - levelling-up and rebalancing were not mere meaningless mantras but core political imperatives. For all its good works, the now defunct North West Development Agency, which once employed 500 people to drive the region’s growth, was more of a hindrance than an enabler for a serious rapprochement between the city’s two main economic players. Determined to uphold scrupulous neutrality between Liverpool and Manchester (it’s Warrington-base memorably described by broadcaster and musical impresario Tony Wilson as being located in the “perineum” of the North West), the agency was forged by a powerful Labour Lancashire mafia, with a brief to prevent and constrain the domineering tendencies of the two cities.

The ill-fated 2001 Joint Concordat between Liverpool and Manchester was only marginally more palatable than the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 which saw the carve up of Poland. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H27337 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

“The idea of Liverpool as a stage set for cultural spectacles and entertainment extravaganzas is a beguiling substitute for an actual economy.”

The Storey-Leese pact conceded Manchester’s status as regional capital, a painful admission of subservience that probably explains the reluctance of subsequent Liverpool leaders to pursue similar overtures. The Liverpool City Region and Greater Manchester devolution deals, and the election of “great mates” Steve Rotheram and Andy Burnham has seen little practical collaboration, beyond occasional media stunts and chummy get-togethers to compare their favourite home-grown pop tunes. Those who expected more than a Northern Variety Hall double act have thus far been disappointed by devolution projects intent on protecting sub-regional domains and denying the compelling reality of geographic and economic interdependence.

We’re two cities less than 30 miles apart, whose fuzzy edges and increasingly footloose populations are blind to civic boundaries that no longer delineate where or how people live, work and play. People are already beginning to see and experience the cities as a single urban place - we just need to dismantle some of the physical and administrative obstacles.

It is beyond farcical that train travel between the two city centres is only marginally quicker today than it was when Stephenson’s Rocket completed its maiden journey two centuries ago. At a pre-MIPIM real estate seminar a few years ago, a Liverpool property professional opined that the single biggest boost to Liverpool’s commercial office market would be a 20 minute train service to Manchester city centre. Who knows, it may even have been enough to persuade Liverpool-nurtured companies like the sports fashion-brand, Castore, to stay in a better connected city location instead of moving to our city neighbour (and taking 300 jobs with it). Questioning the benefits of a fully integrated single strategic transport authority to straddle the two city-regions, is equivalent to advocating the abolition of Transport for London and its replacement by two rival authorities with briefs never to talk to each other.

“Rather than resenting Manchester’s success or investing in a strategy of do-or-die competition, is there a smarter and mutually beneficial alternative?”

For those who ask what’s in it for Manchester, the answer is the well attested and quantifiable benefits of economic agglomeration - cost efficiencies, labour pooling, expanded markets, knowledge spill-overs… Whilst working for the think tank, ResPublica on a project to build the economic case for Liverpool’s connection to HS2, I was staggered to hear Manchester’s economic strategist Mike Emmerich admit that his city envied aspects of Liverpool’s asset-base. The hard and soft criteria by which urban theorists like Saskia Sassen measure the credentials of aspiring global cities, seem evenly dispersed between the twin cities of the Mersey Valley. We can’t match Manchester’s international transport connections, its media and knowledge clusters, but neither can they compete with Liverpool’s global brand, our cultural prowess, architectural grandeur and liveability offer.

If transport is the no-brainer, the wider benefits of agglomeration need to be systematically mapped and identified. The amorphous promise of a Northern Powerhouse can only be realised in physical space, and the contiguity of our two city regions make this the most viable location for a re-balancing project. If the North is ever to grow an economic counter-weight to London, then connecting the two closest jigsaw pieces together seems like a sensible undertaking. Whether its land-use planning or plotting economic development, investment and skills strategies, it’s nonsensical for the two city regions to be pursuing their respective goals in blissful oblivion of what is happening on the other side of an arbitrarily contrived line on a map.

Notwithstanding, its invaluable enabling role in gap funding development and infrastructure projects, the North West Development Agency was a political creation without underpinning logic or legitimacy. Were there ever any connecting threads of economic interest between Salford and Penrith? Wilmslow and Barrow-in-Furness? The Agency’s opaque governance, and its tortuous high-wire balancing act, placating a multiplicity of sub-regional agendas and interest groups, inhibited its ability to optimise the potential of the region’s two great economic engines.

So here comes the controversial bit. Pacts, concordats and convivial personal relationships are simply not sufficient to realise the potential of a new economic relationship between the two city regions - one that acknowledges that their respective asset-bases can be curated for mutual benefit. The only solution is a new governance structure - a devolution model with one Metro Mayor and one Combined Authority. I fully grasp the deeply heretical nature of this proposition, and the threat that it seems to pose to the identity and autonomy of a city that suspects it will be the junior player in any such arrangement. But are identities any more compromised in a ‘Twin City Region’ than they are within the current dispensation? St Helens, Sefton, Wirral, Wigan, Bolton amongst others would probably argue not. The integrity and jurisdiction of the respective city councils and other local authorities would not be compromised - we would only be pooling functions and responsibilities that are already acknowledged to be regional, and projecting them onto a bigger and less artificially contrived regional canvas.

“The only solution is a new governance structure - a devolution model with one Metro Mayor and one Combined Authority.”

Once upon a time, Liverpool and Manchester were authorities under the even more commodious administrative umbrella of Lancashire County Council, and as I‘ve mentioned, more recently, through the North West Development Agency, we were content to buy into the concept of a North West regional project conspicuously lacking any democratic accountability.

In a Twitter / X exchange with Liverpolitan a few weeks ago, I was asked to defend this joint governance proposition by pointing to a successful or established similar model elsewhere in the world. In the US, the twin cities of Minneapolis and St Paul, and of Dallas and Fort Worth, and the urban centres of the San Francisco Bay Area have come together in different ways to pool planning, transportation and economic development responsibilities. Closer to home, the Ruhr Regional Association in Germany exercises both a statutory and enabling role in areas including planning, infrastructure, economic development and environmental protection for the cities of Dortmund, Duisburg, Essen and Bochum. But even if there is no precise template elsewhere, should this be an inhibitor to the cities that built the world’s first inter-city railway, and that pioneered many of the most progressive advances in civic governance in the 19th and early 20th centuries?

In the absence of compelling practical arguments against the proposition, the most likely and persuasive objection will be that the mutual rivalry runs too deep, the antagonism is simply too intense and has festered too long. A ‘One State’ solution for the Liverpool and Manchester City Regions is about as saleable as a one state solution for Israel and Palestine. Maybe it’s an argument that requires a solution or a process rather than a rebuttal. In truth, antipathy is a quite recent addition to a history of rivalry that owes more than a little to the intensity of the competition between the country’s two most successful football teams. Exorcism perhaps requires a practical project, an enthusing collaboration that focuses on shared cultural attributes and ambitions. Somewhere not far away such an idea is maturing, but I will leave it to its progenitors to expand, perhaps on this platform, and maybe very soon.

Of course, there is another motive and spur for this idea which relates to the abject failure of governance within the city of Liverpool and the continuing inability of its dysfunctional political class to nurture or curate those incipient possibilities that so rarely reach fulfilment. The uprooting of Castore from Liverpool to Manchester is an instructive case study, but so too are the games companies, the biotech businesses, legal and insurance firms that have hatched in Liverpool and gone on to prosper elsewhere. Maybe we need governance less rooted in parochial politics and less constrained by cultural legacy. To borrow an analogy from Iain McGilchrist’s Divided Brain hypothesis, perhaps Manchester’s busy-bee utilitarianism and non-conformist pragmatism is the left hemisphere counterpoint to Liverpool’s wistful dreaminess (even our civic emblem is an imaginary being). Is it just possible that our divergent dispositions and outlooks are not actually a prescription for unending antagonism but the formula for a fruitful alchemy?

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

It’s Time to Get Interesting

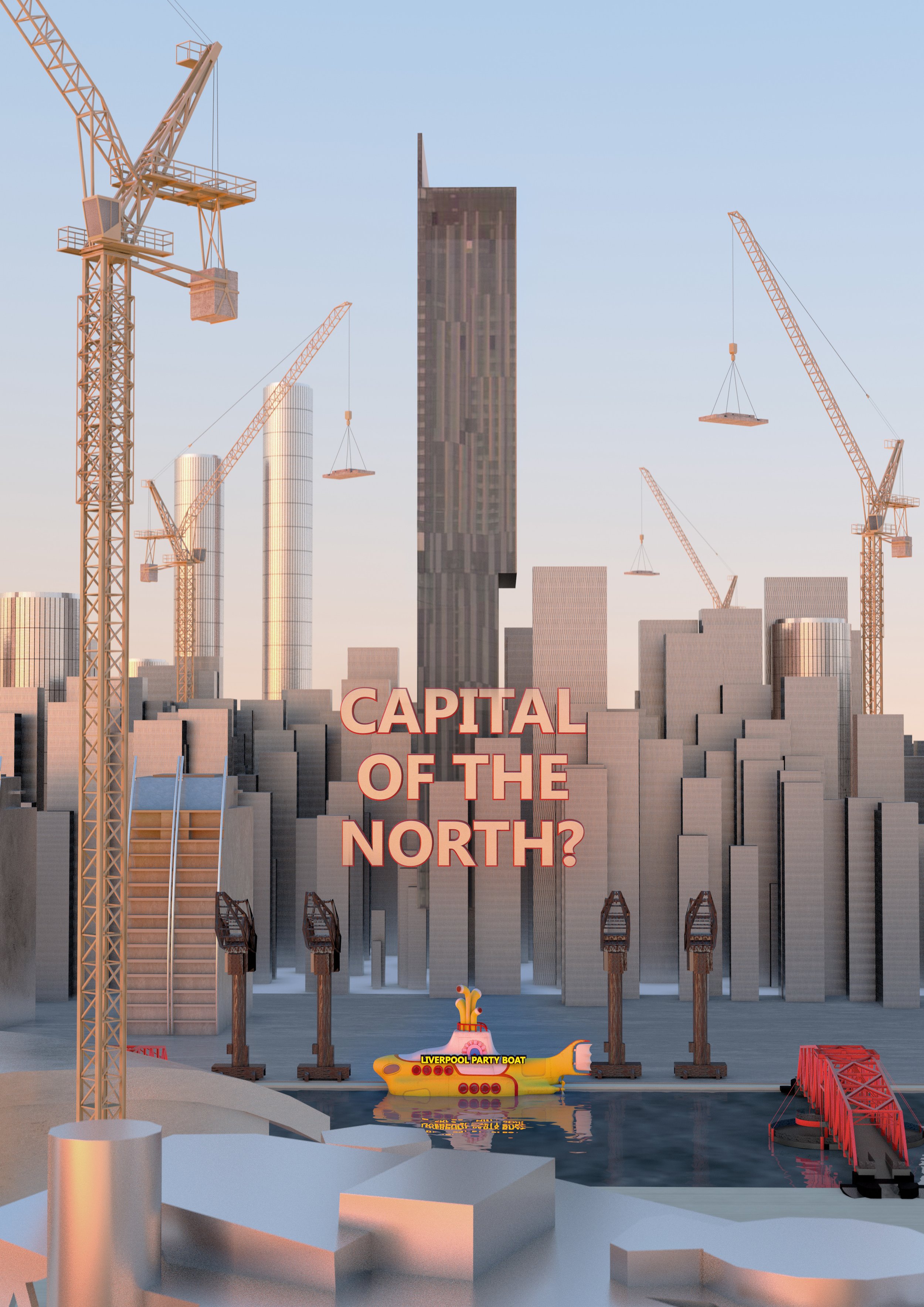

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to Manchester’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

Jon Egan

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to the city’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

This long-forgotten televisual gem was brought to mind by a recent tweet from Liverpolitan which observed, sagely, that when Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of his own city’s expanding psychogeography. Under Burnham’s monarchic reign, Manchester has become the fulcrum of an aspiring northern nation. Its status as capital of the north is beyond dispute. Michael McDonough’s visionary prospectus for Liverpool’s Assembly District as a home for pan-northern regional government (beautiful and inspiring though it is) is destined to remain another sadly lamented ‘what if’. Liverpool’s own claims to northern dominance are a boat that has long since sailed and, like a great deal of our city’s historic wealth and prestige, are now securely moored at the other end of the Manchester Ship Canal.

Sorry if this sounds fatalistic and defeatist, but it’s an unavoidable truth. Manchester as regional capital has already happened and I can’t help feeling it’s actually entirely apposite. Liverpool is not, never has been and never will be the capital of the north for a very simple reason - we’re not in ‘the North.’

Let me explain. Some years ago when pitching for the brief that became the It’s Liverpool city branding campaign, my agency team and I presented an extract from a speech by then Tory Minister for Transport, Phillip Hammond. In it, he had been extolling the benefits of HS2, which he prophesied would unleash the potential of “our great northern cities.” To emphasise the point, and presumably to educate his London-centric media audience, he decided to identify these hazy and distant provincial relics that would soon benefit from an umbilical connection to London’s life-giving energy and dynamism. Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Sheffield, Bradford and even Newcastle (which wasn’t in any way connected to the proposed HS2 network) all made it on to his list. Our pitch focussed on Liverpool’s conspicuous absence from Hammond’s litany. We weren’t (as I opined in an earlier offering to this publication) ‘on the map’. We deduced that the speech was one more piece of definitive evidence that Liverpool wasn’t considered sufficiently great to merit a mention - nor important enough to be connected to a flagship piece of national infrastructure. But on reflection, there may have been another reason for the city’s omission. Perhaps we weren’t sufficiently northern! As if the inclusion of the offending syllables liv-er-pool would have somehow derailed this Lowryesque invocation of smoke stacks, cloth caps and matchstalk cats and dogs.

Of course, we are not talking about The North as a geographic region, or even an amalgam of richly diverse sub-regions, but as a mythic construct. However, as the French philosopher and founder of semiotics, Roland Barthes, would argue, myths are always distortions, albeit with powerful propensities to overcome and subvert reality. In this sense, northernness is not merely a point on the compass - It’s a complex abstraction, a constituent part of the English psyche and self-image that has strong connecting predicates and excluding characteristics. Geography alone is not enough to discern where The North begins and which enclaves and exclaves are to be considered intrinsic to its essential terroir. Isn’t Cheshire really a displaced Home County tragically detached from its kith and kin by some ancient geological trauma?

Thus when Government Ministers or London-based media commentators pronounce on "The North" they are all too often referencing a cloudy and amorphous abstraction defined not by lines on maps, but by indistinguishable accents, bleak moorlands and monochrome gloomy townscapes, nostalgically referred to as ‘great cities’. From this perspective, northerners are seen as honest, hardworking souls, who used to make things (when things were an important source of wealth and national prestige). Though stoical and resilient, they have a tendency, every generation or so, to get a bit bolshy, at which point it becomes necessary to reassure them of their place in our national life by relocating part of a prestigious institution to a randomly selected northern location, or by staging a second-tier sporting event such as the Commonwealth Games or perhaps even placating them with some vague commitment to ‘re-balancing’.

“When Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of Manchester’s expanding psychogeography.”

Manchester has been brilliantly adept at securing for itself more than its just share of these charitably dispensed national goodies. Largely that’s through a typically northern resourcefulness and pragmatism, but also because the city has ingeniously positioned itself as a shorthand synonym for the very idea of northernness.

Peter Saville CBE, the graphic designer who art-directed Factory Records and designed their most iconic album sleeves, also created the acclaimed Original Modern branding for Manchester in 2006. A predictably beautiful piece of graphic creation, it wove a vivid palette of cotton loom colours to represent a new Manchester, that was proud of its pioneering past but wanted to take that innovative DNA to recreate itself in the 21st century. It was wildly popular, but as an exercise in “re-branding” it didn’t succeed in challenging or reframing Manchester’s perceived identity. Instead, it merely set out to transmute it into something more contemporary and serviceable. Saville's project was to dig deeper into the Manchester’s vernacular version of mythic northernness, reflecting no doubt his immersion in Factory's overtly industrial aesthetic. It’s a restatement of core northern traits and a celebration of the city’s long-established narrative - the hub of the industrial north. Manchester’s sense of modernity was less about today and more an evocation of the 19th century, when it was considered the workshop of the world. Its originality was brilliantly expressed by the historian, Asa Briggs, who described it as the “Shock City of the age” - an urban phenomenon without peer or precedent in Europe and only matched by Chicago in North America. Cut forward to the early years of the Noughties. The opening of the ill-fated Urbis project – a new ‘Museum of the City’, conceived by Justin O’Connor and designed by Ian Simpson, was a bold assertion in shining glass and steel of Manchester’s boast to have been the world's first industrial city and the birthplace of the modern age. Despite the powerful statement of brand identity, it was a hopelessly unsuccessful attraction, closing after only two years in 2004. Its director candidly admitted that this monument to the city’s inventive and industrious spirit simply “didn’t work.”

Peter Saville’s Original Modern. Despite the fresh lick of paint, Manchester’s new branding campaign was curiously backward-looking.

In my article, Vanished. The city that disappeared from the map, I suggested that one radical option for Liverpool was to stop trying to compete with its eastern twin. Instead, I argued, we could become a new kind of urban entity - a city with two poles, which pooled our joint assets and balanced the two hemispheres of human consciousness to forge a global metropolis that could re-balance Britain without needing to turn to the patronising benevolence of London. Two hundred years after the building of the world’s first inter-city railway between Liverpool and Manchester, it seemed like a plausible and timely possibility to explore. I was wrong. Not because this idea is manifestly an anathema and heresy to every patriotic Liverpolitan (except me, it seems), but because Manchester is definitively and inexorably set on its own northern trajectory (even to the point where its most creative and happening urban district is aptly branded the Northern Quarter). Unlike Liverpool, Manchester's identity is embedded in its geography, and its literal place in the world. Its compass has only one co-ordinate and it isn’t west.

So where does that leave Liverpool? If we’re not part of The North, where in the world are we? Exiled and dislocated from our northern hinterland, we are a place apart; liminal and strangely detached from mundane geography. The recent media frenzy occasioned by the booing of the national anthem by Liverpool FC fans reignited a predictably shallow rehash of the “Scouse not English" debate, with the now familiar allusions to Margaret Thatcher’s alleged but never conclusively proven project to euthanize the city, compounded by the tragic injustice of Hillsborough. But these events were not the beginning of Liverpool's estrangement from its northern and English identity and its gradual drift to the edge of otherness. When in the second half of the 19th century our “accent exceedingly rare” began to emerge as something radically different to the dialects of neighbouring Lancashire, it was disparaged as “Liverpool Irish” - a vernacular that was deemed to be both alien and inherently seditious. As late as 1958, in Basil Dearden’s film Violent Playground - a British-take on the then topical theme of “juvenile delinquency” - the Liverpool street gang, led by a youthful David McCallum, are portrayed with accents that one reviewer of the DVD release, observed, “curiously owe more to the Liffey (Dublin's river) than the Mersey.” We were quite literally being depicted as foreigners in our own country.

Struggling to find a place within the recognised cartography of northernness, with a figure and stature too grandiose for the peripheral space allotted to us, where in the world can we find a comfortable and fruitful niche? The city that disappeared from the map has only one option - find a new map!

“Liverpool’s cultural programme is undoubtedly worthy, but how many people outside the city can name a single event, festival or programme that happens here?”

Let’s call it the map of interesting cities - places with an ingenuity and energy that is not defined by their geography, and whose confidence and chutzpah aren’t predicated on being the capital of anywhere or anything. Cities whose identity isn’t camouflaged or submerged into anything as nebulous as a region or a point on the compass. So let’s concentrate on being seriously interesting.

It’s a mantel that fits our self-image but we need more than the costume. It’s a project that demands a script and some serious acting. I genuinely think that Liverpool is an interesting city, it’s just that for too long we have marketed ourselves on the basis of our most boring and predictable traits.

We could take our cue from Austin, Texas, a city that markets itself with the slogan “Keep Austin Weird”. It based its civic renewal project on a determination “not to be Houston.” Austin’s promotion of independent business and cutting-edge creativity made it an early poster-child for Richard Florida’s boho-city thesis that diverse, tolerant and culturally cool metropolitan regions will exhibit higher levels of economic development. But Austin’s claim to be an interesting city pre-dates the self-conscious cultivation of weirdness as a kitsch merchandising gimmick. Austin devised and delivered what is now one of the world’s most prestigious gatherings of music, film and interactive media creatives at the annual SXSW festival. It’s an object lesson on how to make space for a genuinely international and seriously ambitious cultural proposition and use it to re-position and redefine a city.

Have we really built on the exposure of 2008 to deliver an internationally recognised programme of cultural events? For all the self-congratulatory posturing, Liverpool’s cultural programme is undoubtedly worthy, definitely diverse but how many people outside the city can name a single event, festival or programme that happens here? For all the energy and inventiveness invested in our pell mell of festive gatherings, we somehow manage to deliver a cultural calendar that is considerably less than the sum of its manifold parts. Places that use cultural events as the pivot for their positioning strategy generally do so by delivering one event or festival of genuine international scale and quality, as Edinburgh, Venice, Austin, San Remo, Cannes and Hay on Wye amongst others will testify. Similarly, “cultural cities” or UNESCO cities of music will normally look to validate that title with a programme that is commensurate with their claim or status.

I’m not going to predict or prescribe the event or theme that Liverpool needs to devise because there are bigger and better informed brains than mine who will be needed for that task. However, I do believe this city can build and sustain an international profile compatible with its brand and reputation by aiming higher and deploying its resources accordingly. For Austin, SWSX was not a travelling circus; it was an integral part of the city’s emergence from the shadows of Houston and Dallas to find its own profile and authentic magnetism. (For more information on Austin’s struggle to maintain its cultural identity try Weird City by Joshua Long).

Being interesting is a vocation. It demands creativity as well as rigorous discipline and hard work. It inevitably requires a style and quality of leadership that is absent from our dismal and discredited local politics. It’s ironic that the one aspect of our civic life that is without question unique and interesting, is so for all the wrong reasons. Liverpool's politics never fails to entertain, shock, frustrate and confound - if only it could achieve and deliver. In the 19th century, Liverpool not only spearheaded ground-breaking projects in rail, building technology and maritime engineering, we were also a wellspring for innovations in public policy and governance. Through pioneering initiatives like the introduction of the district nursing service and public washhouses, and the appointment of the world's first medical officer of public health, Liverpool's civic leaders responded to unprecedented challenges with entirely original structures and solutions. At a time when so many of the established prescriptions and paradigms are breaking down, we need to be plugged into the people and places that are responding creatively to challenges like climate change, technology & the future of work, life-long learning, democratic engagement or the next global pandemic.

Being interesting has to be a behavioural norm that finds expression across every sector and constituency. Are our politics interesting or innovative? Is our media intelligent and stimulating? Are we nurturing our most inventive businesses? Are we doing anything original or brave to address our challenges in education, housing or transport? How do we hope to stem the migration of talent, potential and ingenuity as too many of our best and brightest conclude that this city simply doesn't offer them a future? How do we emulate cities like Austin and become a magnet for innovators and entrepreneurs rather than a departure lounge?

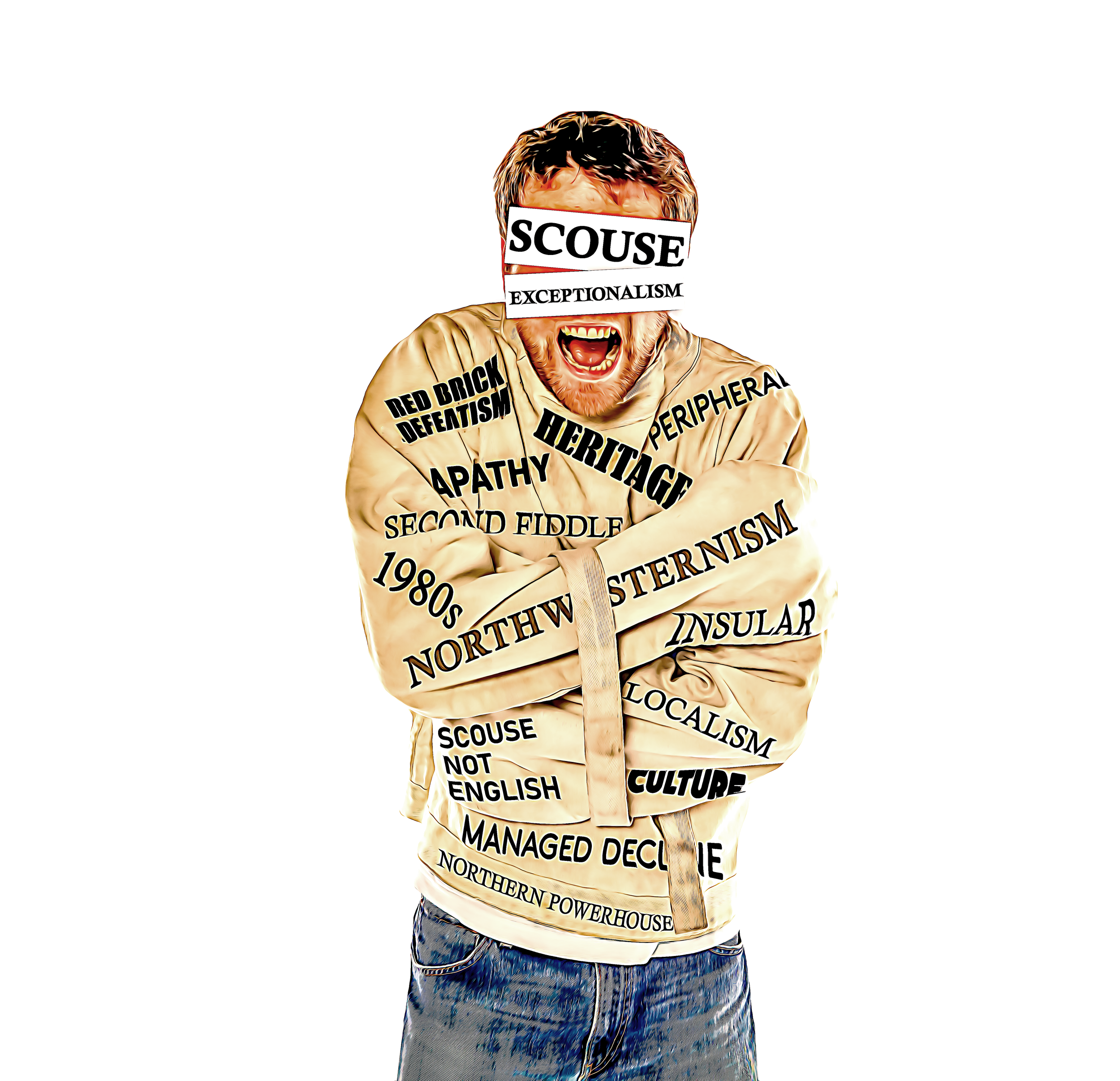

Being interesting is fundamentally about being interested and connected to the wider world! It’s about being aware of what’s happening outside the insular and constricting straight-jacket of scouse exceptionalism or parochial northernness. It’s being open to outside influences and ideas and forging connections and relationships with kindred cities. Maybe we could become the convenor of the interesting city network - a global family of midsize cities free from the gravitational drag of conformity and contingent geography? Cities like Portland, Rotterdam, Hamburg, Auckland and Vancouver whose commitments to liveability and sustainability has sparked inventiveness in transport, urban planning, smart technology and the cultural industries.

If there is a common trait or attitude that connects these cities it is that they are porous, with a capacity and willingness to absorb ideas, influences and people from outside and beyond. Their thinking and ambition is not stunted by a perspective that is either provincial or parochial. They have a place in the world defined more by attitude and outlook than their position on the map. More often than not, they are ports and portals for cultural and human exchange. Auckland and Vancouver have flourished as a direct consequence of immigration, welcoming industrious and ambitious migrants from South Asia and East Asia. Despite our boast to be the World in One City, Liverpool is one of the least demographically diverse cities in the UK. Having at last stemmed our population decline, we are still growing at a discernibly slower rate than comparable cities like Leeds and Manchester. So let's grow our population by becoming an overtly immigrant friendly city, and proactively targeting one potential migrant population with whom we already have an historic and cultural affinity. Doesn't it make sense for the home of Europe's oldest Chinatown to be promoting itself as a welcoming haven for Hong Kong residents fearful of mainland China's increasingly despotic designs on the former colony? "Hungry outsiders wanting to be insiders" was a phrase coined by West Berlin in the 1980s as a strategy to reverse demographic and economic stagnation. It's an approach that a city built for twice its current population could usefully emulate.

Our new narrative can be built on familiar and cherished aspects of (or at least claims about) Liverpool's core identity - open, welcoming and global. But it's time to live them rather than simply intoning them as glib marketing slogans and nostalgic musings. Brands are about behaviour; their truth and utility is measured by what you do, not by what you say, so let's be consistently and ambitiously global not provincial.

In the same way that we need to rethink and curate our cultural programme to be genuinely international in terms of reach and quality, we should be enlisting global talent and expertise to help us rethink and reshape our city. Rather than flogging off prime sites like Liverpool Waters and the Festival Garden to whichever developer or volume house builder is offering the biggest buck, let's hold an international design competition to deliver the most innovative and sustainable new waterfront communities. Twenty years ago, Liverpool Vision was able to excite architects of the calibre of Richard Rogers, Rem Koolhaas, Will Alsop and Norman Foster in opportunities at Mann Island and King's Waterfront. It's a tragic shame that none of their inspired visions came to fruition, but let's resolve to try harder and be clear and consistent about who we are and how we intend to renew and reposition our city.

It's tempting to imagine that being the Capital of the North will transform our destiny in a way that being European Capital of Culture failed to do. But it's not about titles. It’s about a fundamental change in disposition, attitude and culture - and finding a way to overcome the inertia and mediocrity that emanates from our moribund and discredited civic governance.

Above all, it’s about remembering that once upon a time we were the first world city - our compass is omni-directional.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Introducing the Assembly District

History teaches us that no matter which party is in power in Westminster, only the north can be trusted to look after the north. But it should also teach us that the politics of agglomeration are divisive and will not end well for anyone but Manchester and Leeds. But never fear, Michael McDonough offers a solution - tearing up our current constitutional arrangements and establishing a new Northern Assembly for all of the north located on the banks of the Mersey. And he’s only gone and designed it … welcome to Liverpool’s new Assembly District.

Michael McDonough

Quite how Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham came by his coronation in the media as ‘King of the North’ is subject to conjecture.

Some such as journalist and author Brian Gloom speculate that it started as an internet meme, while others wonder whether it was a creation of Marketing Manchester, an agency never shy to position it’s home city as the centre of everything. Whatever its source, and Burnham has himself joked about ruling from a Game of Thrones-style castle, like all good observation comedy, its absurdity is centred on a degree of truth. You’d have to have been operating with your eyes closed since at least the emergence of David Cameron’s government in 2010, not to pick up the sense that Manchester has become the increasingly less unofficial capital of the north, much favoured by business, government ministers and media alike. It’s hard not to notice that whenever the north’s regional mayors get together for a photo op or conference, it’s Burnham that is usually centred as the pivot point around whom others orbit.

You could say this position is much deserved. Over several decades Manchester has played a very successful and canny game and has done much in the running of its economy that is both admirable and instructive to other regions with ambitions to raise their own performance. But this article is not intended as a Manchester love-in. The fear from the outside is that other regions, most notably its closest neighbour Liverpool, are caught in something of a gravity well, heading towards the event horizon, where the blackhole sucking in wealth and talent becomes inescapable.

The UK government appears to have been operating a policy known as agglomeration where the economies of towns increasingly centralise around cities, and the economies of cities are pulled towards the biggest and best of them. The idea is that a northern London will offer snowball effects that drive increasing productivity and opportunity. Any attempt to discuss the downsides are quickly dismissed as jealousy. But what happens to everywhere else? As any real political or investment efforts become increasingly centred on Manchester and Leeds, the north’s other towns and cities are forced to focus on more tertiary and lower value economic sectors to avoid this very obvious elephant in the room. No wonder there’s much discussion about transport. You need good trains and good roads to create a commuter belt.

Whether the north actually needs a ‘King’ is moot, it seems to be getting one, whether it likes it or not. In which case, maybe that King (or future Queen) really does need a castle or administrative centre from which to watch over their lands.

I’m being facetious, of course. But there is one idea that’s been doing the rounds for decades about the governance of the north that never truly goes away, even if no one has quite had the courage to turn it into reality. I’m talking about a Northern Regional Assembly or Parliament – a new constitutional arrangement that would put meat on the bones of devolution. I think it’s worth considering, for two reasons. Firstly, because history teaches us that no matter which party is in power in Westminster, nothing really changes for us. A Northern Regional Assembly would be founded on the simple understanding that only the north can be trusted to look after the north. And the second reason is that, done right, an Assembly could help to counter the divisive politics of regional capitals and agglomeration economics. Power could be distributed in a way that lifts up many communities, rather than few. For this reason an assembly must never be located in Manchester.

‘Let’s aim high. Consign talk of the ‘King of the North’ to the metaphorical dustbin and carve out a new sense of identity and purpose.’

I’ll leave the finer details to minds more attuned to the vagaries of politics and taxation, but it would almost certainly require a bonfire was made of existing local governance arrangements. This would not be yet another fatty layer of bureaucracy feeding off the twitching corpse of local democracy. It would be the pinnacle of a fundamental re-working of power – a place where the core cities and towns of the north would come together to fix and finance their priorities at scale. Cities like Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Newcastle joining forces with the Hull’s, Sunderland’s, Blackpool’s and York’s with one objective in mind – to challenge the economic pull of London and re-position the north as the economic engine room of the UK.

Maybe that sounds fanciful. Can we really reverse the economic gravity of the last 150 years? I don’t know the answer to that but I’d sure like to try. We should have some confidence about what is possible. Most of the UKs core cities reside in the north and our economy is bigger than that of whole countries such as Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, Portugal and Sweden. Our population is made up of 15 million souls and we account for about 20% of the UKs national GDP. While Westminster neglects to address the wealth inequalities that fuelled the demands for Brexit, isn’t it time we took power into our own hands and gave our region a stronger, collective voice? One where different parts of the north were incentivised to put aside regional rivalries and work together.

In which case, I’m going to ask you to imagine a world in which Liverpool becomes the focal point and home of that Northern Assembly. Is that really so far-fetched an idea? Some would immediately dismiss the prospect. Our council is after all essentially under special measures being guided towards competence by government appointed commissioners because we couldn’t manage it ourselves. What credentials do we have? But I’d simply say, why not? We may have had a politically turbulent history and a less than stunning present, but we also have a tradition in the last one hundred years of standing up for the many, not the few. Perhaps there is no more natural home for a regional assembly based on pan-northern equality and fairness as opposed to agglomeration, soft power and resource thirsty regional capitals.

Besides, despite all its issues, Liverpool is a city with an enviable international draw, incredible setting and bags of waterfront space to house such an assembly. A parliament might actually give Liverpool Waters some actual purpose too, while raising our own city’s aspirations. Some of our own will decry it as pie in the sky. But let’s not throw rocks or weave excuses. Let’s aim high. Consign talk of the ‘King of the North’ to the metaphorical dustbin and carve out a new sense of identity and purpose. One that is not only forward looking and aspirational but is also collaborative with its neighbours and based on a desire to see balance, fairness and justice intertwined into the north’s wider politics. it’s already there in the minds and hearts of northern people. Now let’s put it there in the institutions that represent us.

And so in the rest of this article, I’ve taken the liberty of going ahead and designing it. I hope you don’t mind the presumption but they do say a picture is worth a thousand words. I’ve created a series of visuals to conceptualise a new government district centered on Liverpool’s Central Docks.

Assembly District - Principles and Functions

Assembly District fly through.

Today, the site is owned by Peel Holdings and development plans are proceeding at a snail’s pace. A recent consultation was announced for some kind of canalside park, but it’s a blank canvass and no buildings have been announced. The creation of a new political ‘village’ or district laid out to intertwine with neighbouring developments such as Stanley Dock and Ten Streets could be the final piece of the jigsaw for Liverpool’s waterfront regeneration.

This new district would have to accord with some key functional imperatives and some core design principles. For function, the area must be able to accommodate our representatives and supporting administrative staff comfortably and securely. It must capitalise on the economic opportunity by creating desirable workspace which will be attractive to inward investment, and it must be broadly open to the general public to enjoy offering new facilities which are available to all.

From a design perspective, the development should be ambitious and contemporary, forward-looking, sustainable and transparent. This area should boast a ‘postcard design’ while being the embodiment of openness to enshrine in the built form the idea that our representatives work for us, not themselves or even their parties. A trigger for the designs should be northern solidarity. In addition, I’d like to create an element of pleasure through the creation of quality, yet surprising recreational space.

The Ten Streets and Central Docks area today

The Plan

Conceptually, the Central Docks plot would be divided into two areas: river and canal side to the west and further inland to the east. The waterside plots would feature the landmark structures and open space, while the east side could house complimentary mixed-use facilities including both work and residential schemes. Mirroring the adjacent Ten Streets grid pattern, the plans would see a series of new tightly packed, pedestrianised streets opening up the Central Docks site before reaching a series of new waterways and ‘blue spaces’ which will be reclaimed from parts of the site that are currently infilled docks.

New architecture on the site will be encouraged to straddle our quaysides, complimenting and working with water space rather than requiring for it to be filled in to create room for building. This in meant as both a symbolic and practical gesture of compromise in a city often at loggerheads with itself on how to reach for the stars architecturally without compromising existing heritage.

The centre piece of this new district would be the Northern Assembly building. Built across a series of pillars and positioned across the quayside to create a floating form, the building would be in a perfect position for security being largely surrounded by water and accessed only from one side. As a landmark for the north of England, the assembly would feature a circular internal layout to encourage parliamentarians to work together as one collective, while ensuring all areas of the north where represented equally. Cladded in steel and glass, with an undulating façade, the building would take some inspiration from Germany’s Reichstag building in which the public are free to observe parliamentary sessions as part of a commitment to transparency.

On the riverside of the Assembly building, a new public space would be built on a series of interconnected concrete pier structures inspired by Heatherwick Studio’s ground-breaking and beautiful Little Island Park in New York. Each of the up to 50 piers would represent core towns and cities as part of a linear park space on the water’s edge topped with attractive landscaping and robust Mersey-friendly planting. The piers are also symbolic of Liverpool’s position as an arrival and departure point for the whole of the north of England. Together with green spaces throughout the site, reclaimed and newly created blue space and interconnecting bridges this area would become a landmark open space for the city, a riverside space to think, debate, contemplate and engage with politics in a new heart of central Liverpool.

Two other landmark buildings neighbouring the Assembly are proposed for the water-side plot – one striking, multi-use cultural building and one mixed use 35-storey office and hotel.

The office and hotel building has been given a classic robot form with square body, head and antennae – this slightly retro but nevertheless futuristic form pointing to the need to put the industries of tomorrow at the heart of the north's strategy.

The form of the cultural building, which could house museums, exhibitions, performance and meeting spaces as well as a visitors centre, is modelled on a modern interpretation of Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral while it’s four brick turrets are an echo of the city’s landmark Liver Building. The overall effect is somewhat church-like to reflect the central role that faith and secular belief and moral values have in our communities and their deep historical roots in the region.

Transport

One of the key issues facing Liverpool’s central and north docks area is that of connectivity. To compare Central Docks to waterside redevelopment plots in London’s Battersea and Docklands areas it’s clear that a development of this scale and footfall would require a comprehensive transport strategy.

Conceptual design for Ten Streets station, Northern Line.

One possible solution would be the development of a station on the Merseyrail Northern Line to the western edge of the site. Built across existing railway viaducts and positioned equidistant between Moorfields and Sandhills. This new station could multiple audiences including the emerging creative Ten Streets district, Assembly District and also Everton’s Bramley Moore Stadium a few hundred yards north.

One of the key factors slowing down the regeneration of the north Liverpool docks has been access to the city centre and transport in general. Whilst a station at Ten Streets would go a long way to addressing this problem, the influx of new high density development may increase the viability of further transport infrastructure. The plans to the east of Central Docks envisage a concentration of high density homes and commercial and administrative buildings. The substantially increased footfall and employment in the area could support the creation of a new light rail link connecting directly with Lime St station through the currently disused Waterloo/Victoria tunnel alignment.

For illustrative purposes and to create a sense of arrival at the new Ten Streets station, I am proposing two wing-like structures addressing a new public square. Essentially abstract in form, they provide a modern interpretation of the industrial cranes that would once have been seen in the area. They also serve an important function, providing weather-proof covering for 4 escalators which take passengers up to the station’s platform level.

The Northern Assembly is the first of a two part article exploring the development of the Central Docks area. For our next article I will be exploring how the Ten Streets district itself could take advantage of Liverpool’s digital and gaming sector and if extended pull the area closer to the city centre.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Devolution Derailed: When trust turns to dust

The breaking of the mayoral promise for a referendum on the way Liverpool is governed will have lasting effects on voter engagement. Trust has not just been lost, it’s been shat on and flushed into the river. But it’s not too late to change tack. Do councillors have the guts and the smarts to change their minds, put self-interest to one side, and give the people what they desperately need?

Matt O’Donoghue

Elected Mayors. Cabinet or Committee. Devolution. Who wants any of it and who really cares? Well, we all do and those who don’t really should. The more say we have over the way we’re governed, and the way we raise and spend our taxes, the better. But what good is having an opinion about how your city or region is run, if your voice is only listened to but never heard?

A proper referendum – not a ‘consultation’ on just the Mayoral Model – but one that gives the citizens a real choice in how they are governed is what the political nihilists of Liverpool need. Encourage them to step away from the edge, to stop blaming the Tories and their Commissioners, or Joe Anderson and his cronies, and let the people take control of their future.

The current debate over an elected Mayor for Liverpool, and who should have the final say, has more than the malodorous whiff of déjà vu. We could have hot-wired the flux capacitor and jumped into the Doc’s DeLorean to step back to the future of the Cunard’s Council Chambers circa 2012 and barely noticed the difference. Many of the same faces are there. Just as Joe’s army of acolytes did, back when he was Labour Leader of the ruling party, so Joanne Anderson and today’s elected members appear to have snatched the option to choose how their city will be governed from the fingers of its citizens. The best you can say is that it took the current Mayor until January 26th - that’s ten months - to break her manifesto pledge and her media promises for a referendum.

Accusations of ‘betrayal’ and ‘u-turn’ by Mayor Joanne Anderson on this issue, however true they may be, are as pointless as the consultation that her passed amendment is likely to deliver. The binary ‘yes’ or ‘no’ choice that the citizens are likely to get is an exercise that’s estimated to cost £120,000 and will not be legally binding. It serves to appease and to distract. At its core this is about far more than whether to elect a City Mayor. This is about popular engagement and allowing the people to finally have their say over how their city is run; Mayor with a Cabinet, Cabinet and Leader, or Leader and Committee. And it obviously scares them to give the people a choice because our councillors appear to be doing everything they can to make sure this doesn’t happen. Again.

Amid smokescreen-claims that the estimated costs of any full referendum would be £450,000, the Mayor’s post-election pledge that she could be trusted to deliver a legally binding vote have been turned to ashes. As one council insider put it;

“She really should have looked under the bonnet before she promised to put the car back on the road.”

But the importance of a push towards a re-engagement with politics and how the Liverpool City Region’s capital is governed cannot be underestimated. The people of Liverpool deserve this much after being taken for granted, and for fools for so many years. Trust has not just been lost, it’s been shat on and flushed into the river. Never have the people of Liverpool felt more disillusioned with - and more distanced from - those they elect.

When Manchester voters were handed their referendum they chose to reject Mayoral and Cabinet governance and to stick with the Committee system, led until recently by Labour’s Sir Richard Leese. In this city, Labour holds 94 of the 96 seats. Of course, we still ended up with the ‘King of The North’, Greater Manchester Mayor Andy Burnham imposed upon us from above. But in terms of the city authority, we never missed what we never had, a spare Mayor to push the city’s interests. But at least we had our say through a referendum and the people were engaged with the political process. They said ‘no’ in a way that had to heard.

Trust has not just been lost, it’s been shat on and flushed into the river.

When it came to Greater Manchester’s Mayor, like Liverpool, the toy came without instructions. Our two great cities and our regions were political petri dishes. This was Call-Me-Dave Cameron’s experiment in devolved democracy and we just had to get on with things as best we could. But both experiments have had disastrous consequences because transparency and accountability have become an ‘inconvenience’ in the dash towards devolution. I spent the last decade as a journalist exposing the effects of these slippery standards in integrity and investigating the statutory failures of governance and oversight that got us here, in Liverpool and Greater Manchester.

In Greater Manchester, the Mayor was handed the Policing and Crime Commissioner’s duties. Where once we had a monthly Police Committee made up from elected members with statutory powers of oversight and audit responsibilities over the country’s second largest constabulary, now we have Baroness Beverley Hughes who was appointed by Andy Burnham. Oversight has slipped and with it transparency, leaving the Fourth Estate (the media) and its journalists to hold the police to account for their failings and to expose the devastating effects on individuals.