Recent features

Taylor Town Kitsch, Ersatz Culture and the Art of Forgetting

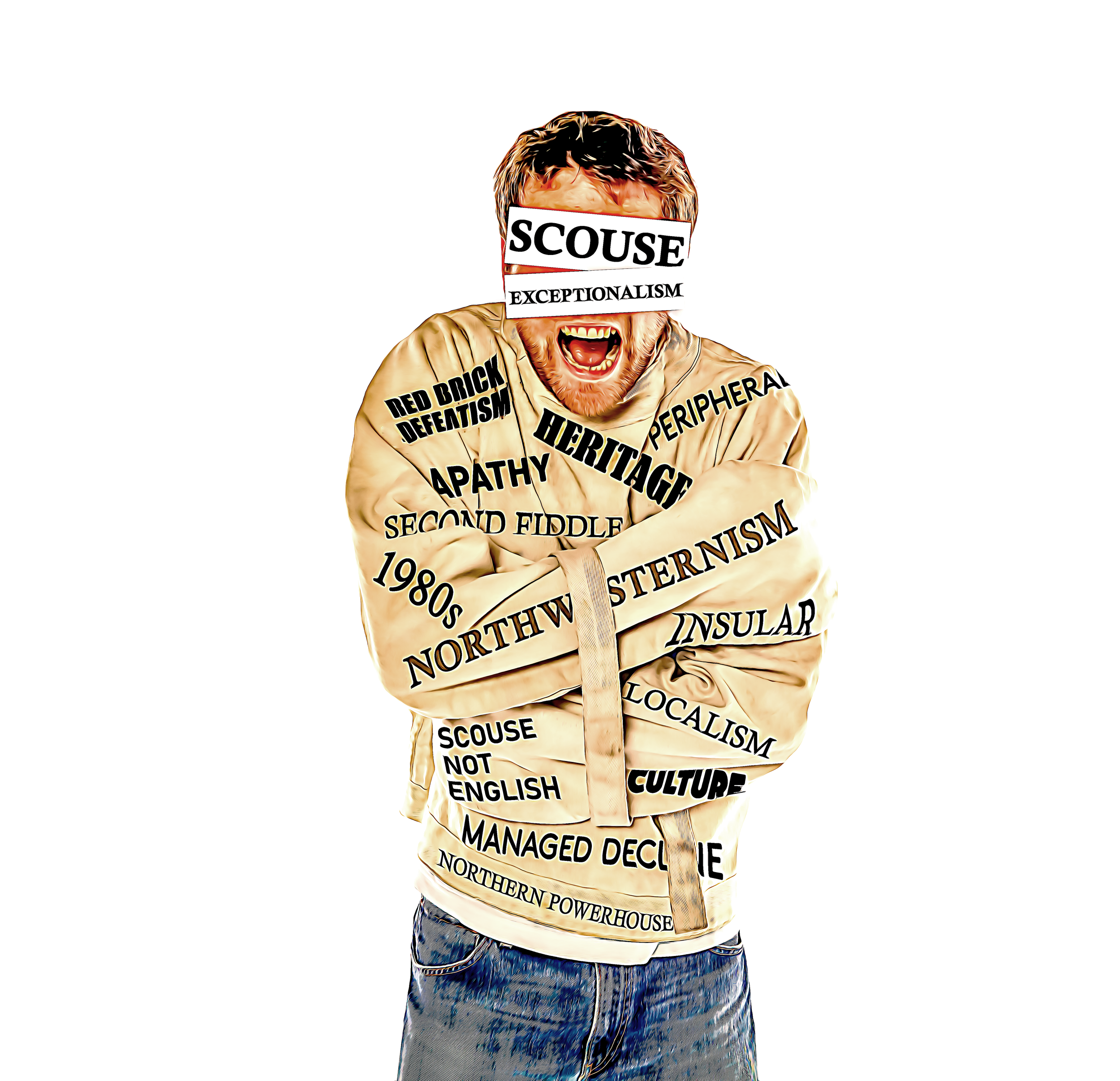

As Liverpool rolled out the red carpet for Taylor Swift, America's biggest pop star and her hordes of cowboy hat-clad 'Swifties' , the city's culture chiefs congratulated themselves on the global media coverage. 'This is who we are' seemed the message. But in this time of forgetting, John Egan wonders, is kitsch really who we are and what we want to be?

“If we don't know where we are, we don't know who we are,”

Jon Egan

It may seem perverse to even pose this question, especially as Liverpool was only recently judged by Which? as the UK's best large city for a short break by virtue of its “fantastic cultural scene”. But ask it I must. Despite once proudly wearing the title of European Capital of Culture of 2008, is Liverpool really a cultural city? To paraphrase the BBC's celebrated Brains Trust stalwart, C.M Joad, I suppose it all depends on what you mean by culture?

My worry is that Liverpool appears to be operating under an increasingly narrow and debilitating definition of culture, or at least, offering to the world a version of its cultural self that seems weirdly stunted, shallow and ultimately synthetic - something the American art critic and essayist, Clement Greenberg might have characterised as ‘kitsch’. Writing in 1939, Greenberg's essay 'The Avant-Garde and Kitsch' defined the latter as embracing popular commercial culture including Hollywood movies, pulp fiction and Tin Pan Alley music. He saw kitsch as a product of rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, which created a new market for “ersatz culture destined for those who, insensible to the values of genuine culture, are hungry nevertheless for the diversion that only culture of some sort can provide.” These mass-produced consumer artifacts, by definition formulaic and for-profit, had driven out "folk art" and authentic popular culture replacing it with what were essentially commodities.

One does not have to be a Marxist (Greenberg was) or a cultural snob (he was possibly one of those as well) to be slightly worried that Liverpool's cultural brand is beginning to lean too heavily in the direction of the kitsch and the hyper-commercial. It was a concern, first articulated in the run-up to Liverpool's hosting of Eurovision last year by the Daily Telegraph’s Chris Moss, “Liverpool has chosen Eurovision kitsch over protecting its history and heritage”, and explored further in my Liverpolitan article, “Liverpool's Imperfect Pitch”. A feeling that has only been exacerbated by the recent Taylor Town phenomenon.

For the somehow blissfully unaware, Taylor Town was a “fun-filled” council-funded initiative to transform the city of Liverpool into a Taylor Swift “playground” designed to offer a “proper scouse welcome” to the American pop star and her legion of fans before three sell-out shows at the Anfield stadium. This included commissioning eleven art installations each symbolising one of the artist’s 11 albums – everything from a moss-covered grand piano to a snake and skull-clad golden throne – all designed to be instantly instagrammable.

A golden throne inspired by Swift's 'Reputation' era forms part of Liverpool's Taylor Town trail conveniently located for lunch options. Image: Visit Liverpool.

Sure, Liverpool wasn't the only port of call on Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour to dress-up for the Swifties, but wasn't there something about the hype and hullabaloo that went beyond due recognition and celebration of a major musical event?

My queasiness about Liverpool's Taylor Town re-brand is more than mere snobbishness, or a patronising disdain for popular culture. Our willingness to conflate the city’s very identity with the persona of the American pop icon carries worrying echoes of Councillor Harry Doyle's “perfect fit” mantra between Liverpool and Eurovision. This is somehow more than just a smart bit of opportunistic marketing; it implies some deeper and integral affinity. Public pronouncements by Doyle and Claire McColgan, invoking the spirit of Eurovision, suggested Swift's visitation was seen as an epiphanic moment of self-realisation. In a spirit of almost quasi-mystical reverie, Clare McColgan explained; “the world can be a very dark place and in Liverpool, it’s light.”

If Taylor Swift has somehow become the embodiment of our cultural identity and ambition, what exactly have we become? The American cultural writer and scholar, Louis Menand observed, “in the 1950s the United States exported a mass market commercial product to Europe [rock n roll]. In the 1960s, it got back a hip and smart popular art form.” He is, of course referencing The Beatles and sadly it seems that we are once again being sold short on this cultural transaction.

“Liverpool's cultural brand is beginning to lean too heavily in the direction of the kitsch and the hyper-commercial.”

Despite Doyle's claim that her arrival “was very much in the spirit of the city's musical history”, Taylor Swift is not The Beatles. In the words of the Canadian feminist writer and blogger, Meghan Murphy she “will be forgotten in 20 years, which cannot be said for Janis Joplin, Carly Simon, Etta James, Leslie Gore, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Whitney Houston, Aretha Franklin, or Tina Turner... And none of those women made it on account of being beautiful or having a string of celebrity boyfriends. Certainly, they will not be remembered for their ability to command the hysterical attention of legions of young fans. They were just very good.”

Swift may be a global superstar, a role model and a performer with genuinely admirable philanthropic and compassionate sensibilities, but she is also according to Murphy, bland, manufactured and ephemeral - the literal embodiment of kitsch. Merely staging one of her concerts does not boost our cultural capital or say anything true or meaningful about who we are. For Harry Doyle, the sheer scale of global media coverage is its own justification. “So far, our city has been featured on just about every media outlet worldwide, including the Today Show in the US”, he excitedly claimed, as if a simple volumetric calculation was enough to establish cultural prestige.

Making “the city part of the show” to quote Claire McColgan, and building a civic and cultural brand by staging big events, was the thesis underpinning the city's post-Capital of Culture prospectus, The Liverpool Plan. Describing Liverpool itself as “The Great Stage” it prefigured a reality that those concerned about the condition and accessibility of our waterfront and parks are beginning to realise has troubling consequences. There may well be a perfectly credible argument for hosting large scale events and showcasing the city's architectural and heritage assets, but this is no substitute for what cities, once saw as their responsibility to promote and nurture culture in its widest sense.

So, do we need a different yardstick for what makes a cultural city? If Liverpool wasn't a cultural city, or had not been a cultural city, then I would in all probability not be here. When my father accepted a job in Liverpool it was intended as a stepping-stone to Dublin, the city where my parents had met and always aspired to settle down. It was the discovery that Liverpool possessed everything that Dublin promised, that persuaded them to put down roots in a place that satisfied all their cultural appetites. This was a time when both UK and international opera and ballet companies regularly visited our city, when cutting-edge theatrical productions had their pre-West End runs in the city's array of thriving theatres. It was also the time when Sam Wanamaker was transforming the late lamented New Shakespeare Theatre into what The Guardian described as “one of the first multi-strand art centres in Europe” - a venue that was open 12 hours a day, staged contemporary theatre as well as films, lectures, jazz concerts and art exhibitions and put on “free shows for workers every Wednesday afternoon.”

“Taylor Swift may be a global superstar with admirable philanthropic sensibilities, but she is also bland, manufactured and ephemeral - the literal embodiment of kitsch.”

Moss-covered piano inspired by Swift's 'Folklore' era, one of eleven exhibits that made up the Liverpool Taylor Town trail. Image: Visit Liverpool

From the 19th century onwards, culture was embedded in Liverpool's civic project, the city’s self-image being proudly cosmopolitan rather than prosaically provincial. “High Art” might not be the exclusive criterion for what constitutes a cultural city, but it was, for a time at least, integral to Liverpool’s claim to that status. Now it would appear that culture has no intrinsic value other than as a means to an end. Taylor Town was, in Doyle's words, “much needed PR the city needs to attract investment and visitors.”

The irony is that a positioning or investment strategy focused on big events and blitz publicity is quite probably a less effective strategy than one focused on stimulating cultural quality and diversity of offer. Events may deliver a short-term boost to the tourism and hospitality sector, but smart cities understand that the depth, quality and originality of their cultural offer is what draws investment and attracts and retains people. Once again, it might be instructive to look to our regional neighbour, Manchester for inspiration. The Manchester International Festival (MIF) not only reveals a city that, unlike the organisers of LIMF (Liverpool International Music Festival), understands the meaning of the word "international," but is also a masterclass in intelligent place marketing. MIFs inspired, left-field commissions and collaborations are deftly configured to spell out one simple message - “Hey, we're just like London.” In other words, we're the sort of city that's ready-made for banished BBC executives, relocating corporates, boho entrepreneurs or the English National Opera (ENO). Manchester benchmarks its cultural strategy against cities like Barcelona and Montreal, disruptor second cities harbouring global ambitions.

There was a sad inevitability about the ENO relocation to Manchester after Liverpool had failed to make it beyond the shortlist. Liverpool's city leaders offered a flimsy defence of their laissez-faire approach to pitching - that this was a process-driven exercise where lobbying and advocacy were superfluous and potentially counterproductive. Yet as a well-placed Manchester source explained, “Yes, it was process-driven, but the timing worked for us, coming [so soon] after the Chanel Show which secured exactly the right kind of media coverage.” (Note - quality not quantity) “But the key was the availability of a versatile and conveniently available performance venue designed by Rem Koolhaas, that didn't really have a defined function or use-strategy.” The commissioning of The Factory / Aviva Studios was an audacious exercise in the ‘build it and they will come’ approach to urban regeneration, and proof that Manchester, like the Biblical wise virgins, is a city always primed with a trimmed wick and plentiful supply of oil.

Probably, a more significant consideration was the perception that Manchester had an audience for opera whilst Liverpool possibly did not. One of the most depressing episodes in my professional life came during a discussion with Liverpool's big cultural players whilst working on ResPublica's HS2 for Liverpool advocacy project. A prominent, though now departed, head of a prestigious cultural institution, lamented that they would love to deliver a more ambitious programme (as they had in 2008) if only they could “attract an audience from Manchester.” Yet as the success of Ralph Fiennes' Macbeth production at the Depot venue proved last year, this comment is as ill-informed as it is profoundly dispiriting.

“From the two fake Caverns and tat memorabilia of Matthew Street to the anodyne mediocrity of “The Beatles Story”, we are now celebrating what was once subversive popular art in the guise of the mass-produced ersatz culture to which it was once the antidote.”

The Beatles Story: A fake grave cast in authentic-looking granite to a fictitious character Paul McCartney claims he ‘made up’. Could this be any more ersatz or is it just ‘meta’?

Photo: Paul Bryan

For all its sophistication and legacy of transformed cultural assets, there is still a whiff of utilitarianism about Manchester's approach, and a view of culture as primarily an instrument of economic regeneration. Hence an emerging new strategy with a greater emphasis on what they term “cultural democracy” with a more equal and diverse distribution of cultural resources and opportunities.

Notwithstanding the undoubted quality of our visual arts assets and collections, Liverpool's performing arts offer is now sadly diminished and, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra excepted, is hardly commensurate with what you’d expect of an aspiring cultural city. If Liverpool is to entertain genuine claims to that title, then maybe we need another definition that isn't founded merely on physical assets or an eye-catching events programme?

For American essayist and poet, Wendell Berry “culture is what happens, when the same people, live in the same place for a long time.” For Berry “same people” doesn't entail ethnic homogeneity. His own Appalachian culture is a heady brew of English, Scots Irish, Cherokee and African influences that even a fledgling Taylor Swift, once wanted to get a piece of. His definition is closer to what Clement Greenberg saw as the antidote to kitsch - “folk art”. This is culture with roots, with an organic and intimate connection to place, with a character, accent and disposition that are distinctive and inimitable. By this yardstick, cultural cities are not just places that stage culture or boast a wealth of cultural assets, they also cultivate and disseminate it. It is in this sense that Liverpool can perhaps advance its most convincing claim to be a cultural city.

Liverpool's culture is as much an ambience and attitude as it is an archive of expressions and artefacts. It emerges in creative convulsions that emanate from a deep geology, a substratum of shared stories and memories. In the 1960s, it was Merseybeat, the poetry of McGough, Patten and Henri, the forgotten genius of sculptor, Arthur Dooley, and the phantasmagorical humour of Ken Dodd. (Are the jam butty mines of Knotty Ash just charming whimsy or, like Williamson's Tunnels, secret portals into the arcane depths of Liverpool's collective unconscious?). The early noughties, as the city began to dream of becoming a European Capital of Culture, happily coincided with another creative spasm, as Fiona Banner was shortlisted for the Turner Prize, Paul Farley won the Whitbread Poetry Prize, Delta Sonic Records were trailblazing Liverpool's third musical wave, and Alex Cox was back in town collaborating with Frank Cottrell Boyce on their, as yet unrecognised masterpiece, Revenger's Tragedy.

“Memory is the alchemy that transmutes the base metal of the everyday into the life-enhancing elixir of an authentic culture. But we live in a time of forgetting, of uprootedness, fracture and disinheritance, and even a city famed, and often derided, for its obsessive nostalgia, is not immune from this pervasive fixation with the immediate, the superficial and the kitsch.”

It's not just the social realist triumvirate of Bleasdale, Russell and McGovern whose writings are moored in the anchorage of their home port city. For novelists like Beryl Bainbridge, Nicholas Monsarrat and Malcolm Lowry, Liverpool looms and lurks in the shadows of their fiction even as a point of departure or an unspoken absence. For two contemporary Liverpool writers, the city is an object of almost erotic communion. Musician Paul Simpson's gorgeously poetic memoir, Revolutionary Spirit, and Jeff Young's Ghost Town are immersions in secret treasuries of memory and miracle. Young is Liverpool's cartographer of the marvellous, tour guide to our fevered Dreamtime for whom Liverpool “is the haunted place of remembering.”

Memory is the alchemy that binds past and present, that invisibly entwines the living with the dead. It's what transmutes the base metal of the everyday into the life-enhancing elixir of an authentic culture. But we live in a time of forgetting, of uprootedness, fracture and disinheritance, and even a city famed, and often derided, for its obsessive nostalgia, is not immune from this pervasive fixation with the immediate, the superficial and the kitsch. In a blisteringly brilliant essay in The Post, Laurence Thompson poses the question, why is Liverpool unwilling or unable to recognise the creative achievement of filmmaker and “great visual poet of remembrance,” Terence Davies, and his seminal trilogy Distant Voices, Still Lives?

“That such an impressive work of art came both from and was about Liverpool seems worthy of commemoration. Yet it’s impossible to imagine the Royal Court commissioning a major contemporary playwright to adapt a stage revival of Distant Voices, Still Lives... I’m not advocating Davies’s memory falling into the hands of the usual custodians of Liverpool’s heritage. What’s the point in putting up a blue plaque commemorating the original Eric’s when the current Eric’s is so unbelievably shite? But the choice between amnesia and kitsch must be a false dichotomy.”

The French seem more inclined to remember the seminal films of Terence Davies, than Liverpool, the city of his own birth. A retrospective held at the Paris Pompidou Centre in March 2024.

Alas, it seems we are increasingly opting for kitsch, not just in terms of our desire to bask in the reflected aura of Eurovision and Taylor Swift, but also in how we package and commodify our own cultural legacy. From the two fake Caverns and tat memorabilia of Matthew Street to the anodyne mediocrity of “The Beatles Story”, we are now celebrating what was once subversive popular art in the guise of the mass-produced ersatz culture to which it was once the antidote. Kitsch's suffocating omnipresence is a soporific that dulls memory and transports us into its own featureless geography. “If we don't know where we are, we don't know who we are,” explains Wendell Berry. For Berry, culture, identity and place are a sacred trinity without which human society withers and sinks into the shallow abyss that G.K. Chesterton termed the “flat wilderness of standardisation.” A time of forgetting is also a time of false belonging. Polarised politics, bitter culture wars and horrifying street violence are in different ways a thrashing around in search of connections to something enduring and meaningful in the bewildering Babel of post-modernity.

Consigning an artist of Terence Davies' stature to the margins of oblivion is sinful enough, but it is emblematic of a deeper estrangement and disconnection. A city that squanders its World Heritage Status, that's indifferent to its own cultural history and cheerfully embraces an architectural aesthetic of shabby and soulless mediocrity, is forsaking its very identity. In the spirit of Louis Aragon's Le Paysan de Paris, Jeff Young chronicles Liverpool’s neglectful disregard for the overlooked, the curious and the idiosyncratic, for the magnetically charged spaces and landmarks, like the sadly demolished Futurist cinema, that are the coordinates of our collective remembering. Ghost Town is an odyssey in search of a submerged city, drowning under the dead weight of the bland and the banal.

“The magic is leaching from the city, the shadows and alleyways are emptying, and so we walk through wastelands where the magic used to be, we gather autumn leaves from gutters and dirt from the rubble of demolished sacred places.”

Identity and culture are rooted in the original, the distinctive and the unwonted, in things that should be reverenced, not wilfully expended.

At the conclusion of his Gerard Manley Hopkins Lecture at Hope University earlier this year, I asked Jeff, how do we breach the chasm that seems to separate those who love the city, from those who govern it? There isn't a simple answer, but it must surely involve some thoughtful consideration of what it means to be a cultural city. Culture in its authentic form, is salvific. Being connected to a place, its story and to each other is to fulfil one of our most basic human yearnings.

For now, at least, the circus has left town. Eurovision and Taylor Swift have moved on to the next “destination.” But if we want to get in touch with our culture, we need to see through the eyes of poets and artists like Jeff Young and Terence Davies, to look beyond the empty stage for something part-buried and only half remembered - the immeasurable richness of a cultural city.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Main Image: Paul Bryan

What next for the Wirral Waterfront?

As a child I found Wirral, and Birkenhead in particular, to be a deeply mystifying place. I knew that Ireland, where we went on holiday, was across the water, but where exactly was this other place? It wasn’t Liverpool, but was it even England or maybe Wales, or some strange liminal place existing outside my primitive geographical understanding?

Jon Egan

As a child I found Wirral, and Birkenhead in particular, to be a deeply mystifying place. I knew that Ireland, where we went on holiday, was across the water, but where exactly was this other place? It wasn’t Liverpool, but was it even England or maybe Wales, or some strange liminal place existing outside my primitive geographical understanding?

My earliest journeys across the Mersey did little to dispel Wirral's sense of disquieting otherness. The deep, dark descent into the underworld of the Mersey Tunnel only reinforced its obvious detachment from humdrum reality. This must be the other side of the looking glass.

Years later during my counter-cultural phase, and in the spirit of Parisian Surrealist explorations, we’d take “the metro” to Birkenhead in search of the merveilleux. Birkenhead’s numinous aura was only magnified by the eerie absence of people, the monumental grandeur of Hamilton Square echoing the ominous emptiness and abandonment of Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical city scapes.

In later years my associations with Birkenhead became more prosaic and practical through involvement in a succession of aborted regeneration initiatives and "visionary" but unrealised masterplans. Spending days talking to frustrated residents and world-weary stakeholders I was struck by their sad fatalism, as if the town had been subject to some strange and enervating enchantment. As Liverpool’s cityscape was magically transformed before their very eyes, Birkenhead seemed frozen in a state of suspended animation akin to Narnia trapped in its perpetual winter.

But of course there was nothing supernatural about the decline of Birkenhead. Once styled the City of The Future, Birkenhead has a proud and pioneering history. In addition to its global shipbuilding prowess, it’s the town that built the UK’s first public park, its first Municipal College of Art as well as Europe’s first tramway. Birkenhead’s curse is a toxic blend of economic decline and disastrous urban planning, making Birkenhead a place that’s easier to pass through than get to. Whilst cars, people and investment pass Birkenhead by, it’s tempting (and partially true) to point the finger at poor leadership and botched planning. But is there another more fundamental reason for the town’s baleful situation? Is it rooted in Birkenhead and Wirral’s deeper crisis of identity?

Regeneration has to be informed and framed by a sense of place - a clarity of purpose and identity. Without an existential paradigm regeneration is likely to be a series of disconnected and arbitrary interventions, very often aiming to undo the unforeseen consequences of a previously failed intervention. Birkenhead shopping centre is a palimpsest of flawed visions and ham-fisted initiatives. It is still just about possible to discern the archaeological remnants of what was, once upon a time, a high street (Grange Road), dissected, butchered and disfigured by ugly and already half-redundant modernist protuberances . This is town planning re-imagined as self-mutilation.

In 2001 Wirral Council attempted to resolve the peninsula's ambiguous identity with a bold, but alas unsuccessful bid for City Status. This was always a difficult proposition to sell given the uneasy relationship between the borough's urban Mersey edge and its bucolic hinterland. If Wirral isn't a city, then what is it? A municipal construct? A geographical descriptor? A lifestyle aspiration? Is it one place or an amalgam of places with quite different characteristics, histories and identities? It is difficult to suppress the suspicion that the failure to arrest the decline of its distinct urban centres has something to do with their slow immersion and disappearance into an amorphous and confused abstraction. It's little wonder that a Council without a settled sense of identity (its fractious communities historically divided about whether they should have an L or a CH postcode), should struggle to formulate or deliver a coherent regeneration vision. To borrow a Marxist analogy, Wirral's debilitating dialectic needed a resolving synthesis - and happily they found one.

‘Downtown Birkenhead needs to re-orientate itself and define its future in relation to an already burgeoning Liverpool City Centre…’

The Wirral Local Plan (currently awaiting Government approval) ingeniously united the borough's disparate communities and political factions with a strategy to vigorously defend its greenbelt and direct all new housing development onto urban and brownfield sites. Implicit in the plan are two revelatory and foundational propositions.

1) Wirral is not a homogenous place - its Mersey edge is a connected urban strip that is qualitatively different from the pastoral commuter settlements west of the M53. (Income disparity between the borough's most deprived and affluent areas is greater than in any other UK local authority area.

2) The history, identity and future of the urban edge is umbilically connected to the place it stirs out at across the Mersey (but sometimes thinks exists in a different hemisphere) - it’s Liverpool’s Left Bank.

Wirral's Left Bank vision was a new regeneration narrative to reposition and re-imagine the Mersey shore, but is also the core strategy against predatory housebuilders’ determination to challenge the no passaran defence of the greenbelt. However, this defence would only be sustainable if Wirral could make the Left Bank a sufficiently attractive and commercially rewarding location for the scale of building necessary to meet the borough's new homes requirement.

And herein lies the challenge. From New Ferry to New Brighton, the Left Bank littoral has, in recent decades - with one gloriously idiosyncratic exception (more later) - been a virtual regeneration exclusion zone. Turning what is often perceived as Liverpool's down at heel urban annexe into a thriving regeneration powerhouse is a challenge requiring exceptional presentational and practical capabilities.

The presentational brief has been curated by an impressive creative team, combining the branding and visualising expertise of designer, Miles Falkingham with the editorial acumen and eloquence of Birkenhead writer, David Lloyd, The Left Bank mood board, flawlessly realised in the eponymous digital and print magazine, presents a richly fertile incipient oasis, pregnant with possibilities and welcoming to innovators, prospectors and the independently inclined.

Birkenhead Dock Branch Park, conceptual visualisation.

The Left Bank

As a destination for the discerning, Left Bank is a counterpoint to a Right Bank (Liverpool) whose identity and character is being lost under the stultifying uniformity of the standard regeneration model.

But the Left Bank idea is more than a cleverly crafted re-branding exercise. It is also a set of values and sign posts to inform the delivery of what is potentially Wirral's most transformational regeneration windfall. Birkenhead 2040 outlines a radical vision for a re-imagined Birkenhead town centre underpinned by a series of successful Levelling Up and Town Deal funding awards totalling £80 million.

In 2016, following on from my involvement in a consultation on yet another undelivered regeneration project, I was one of a small group who produced an unsolicited document sent to Wirral's then Regeneration Director, entitled Manifesto for Downtown Birkenhead. A call to arms, it's opening paragraph set out the key challenge and imperative:

"Downtown Birkenhead needs to re-orientate itself and define its future in relation to an already burgeoning Liverpool City Centre. Reaching out and strengthening its sense of proximity and connectedness will be vital in attracting the energy, activity and people that are currently absent from a once vibrant centre."

The content was a series of ideas offered or identified during our conversations with stakeholders, or arising from immersive wanderings around a town rich with unique and under-utilised assets. The ideas included creating the region's best urban market, transforming the abandoned Dock Branch railway into Birkenhead's "low-line" and creating a venue for the town's burgeoning new music scene. In 2019 a Festival of Ideas, held as part of Wirral's Borough of Culture programme rehearsed these and other possibilities that would become the anchor ideas for the successful funding bids.

But with both the ideas and funding to deliver transformational change, doubts are emerging as to whether Birkenhead may once again squander a golden opportunity. Following a flurry of key officer departures, including Alan Evans, the Regeneration Chief widely credited with delivering the successful funding bids, concerns are growing that the Council lacks the organisational capacity and technical skills to translate tantalising visions into tangible realities.

‘…it’s something that people would be willing to get off a train for.’

More worrying still, it is now highly probable that pragmatic imperatives will lead to the abandonment of one of 2040's flagship projects. When visionary Dutch architect Jan Knikker was engaged in 2015 by Liverpool developers, ION, to feed into their Move Ahead, Birkenhead masterplan, the possibility of an urban market as unflinchingly radical as his Rotterdam masterpiece became a beguiling statement of ambition. After all, Birkenhead had been a market town, and a re-imagined, relocated modern urban market was the one thing Liverpool didn't have to offer. In the words of Birkenhead Councillor and Wirral Green Party Co-Leader, Pat Cleary, "it’s something that people would be willing to get off a train for."

Citing spiralling costs, the proposal for a new market on the site of the former House of Fraser store at the interface between the St Werburgh's Quarter and the proposed Hind Street residential quarter, would now appear to be dead in the water. A proposal to move the existing market traders into the former Argos store in the Grange Precinct, which is owned by the Council, is being presented as a smart value for money solution that turns a vacant liability into a source of much-needed revenue.

For Cleary, this would be more that the death knell of one of 2040's most transformational projects, it would signify, in his words the replacement of a genuine "regeneration perspective by an asset management mentality." For Cleary, the future of the market is emblematic. If one piece of a coherent jigsaw can be removed, where does that leave projects like Dock Branch Park that could just as easily begin to look expensive and expendable. His is not a lone voice, Birkenhead MP, Mick Whitley, called on the Council to reaffirm its commitment to the new market, warning that the revised option "would mean years of work up in smoke." Following a fraught Council meeting on December 6th, it appears these concerns are unlikely to be heeded. Although officers were instructed to investigate two other options including refurbishing the existing market hall, the House of Fraser site looks likely to remain a boarded up monument to failed ambition.

Others intimately involved in the evolution of the 2040 vision are also worried that the integrity and spirit of the 2040 vision could be lost in delivery. Liam Kelly, whose Make CIC organisation is a key partner in the delivery of the proposed creative hub in Argyle Street, is willing to accept the need for pragmatism, but favoured a less costly iteration of the existing plan on the proposed site, explaining, "it doesn't have to be expensive to look great." For Kelly, the litmus test for 2040 overall will be the Council's willingness to sustain the coalition of stakeholders and co-creators who have worked with the Council in shaping the vision. As the various funding strands are blended and the overall delivery architecture is refined, Kelly believes, it's about "having the doers around the table and how difficult decisions are made" that will safeguard the integrity and deliverability of the 2040 blueprint.

‘Seeing the tragic and seemingly inevitable decline of the once vibrant Victoria Street, local entrepreneur, Dan Davies, embarked on a uniquely eccentric and joyous regeneration adventure.’

With a final decision on the market project now scheduled for February, the omens point increasingly in the direction of Argos. Both Cleary and Kelly stress the much bigger picture perspective that is somehow absent from the beancounting calculations underpinning the Argos proposition. Without a radically different and vibrant Birkenhead town centre, the viability and credibility of plans to build thousands of new homes on brownfield land at Hind Street and Wirral Waters becomes highly questionable. With Leverhulme Estates already launching a legal challenge in support of their plans for 800 greenbelt homes, the pressure on the Local Plan, and the fragile political consensus underpinning the Left Bank idea, may begin to exhibit destabilising cracks and fissures.

Away from Birkenhead there is another equally worrying indicator that when push comes to shove, pragmatism and asset management logic may be taking precedence over a commitment to the Left Bank aesthetic. There is no known precedent or template for the extraordinary regeneration story of Rockpoint and New Brighton. Seeing the tragic and seemingly inevitable decline of the once vibrant Victoria Street, local entrepreneur, Dan Davies, embarked on a uniquely eccentric and joyous regeneration adventure. Buying up empty and semi-derelict shops, he commissioned internationally renowned street artists to execute a series of spectacular murals celebrating the history, culture and identity of the town memorably dubbed, The Last Resort, by photographer Martin Parr.

This was not just about a lick of paint or a superficial facelift to cheer the spirits. Davies's restless energy and obsessive Canute-style audacity has reversed the tide of decline by bringing new businesses, cafes, venues, an art gallery, pub, recording studio and performance space to make Victoria Street possibly one of the most visually and creatively eclectic high streets in this part of England.

With an offer that caters for every demographic - from disadvantaged young people to socially isolated older residents - the breadth of Rockpoint's improvised and quirky inclusivity was perhaps most perfectly expressed in Hope - The Anti-Supermarket. Occupying the thrice-failed food store, Rockpoint transformed the unit into a multi-use space for artisan and independent retailers, social events, comedy, music and local am-dram performances. At a time when communities everywhere are witnessing a diminution of social capital and public space, Davies was delivering, under one roof, the kind of outcomes that 2040's proposed "creative" and "wellbeing hubs" can only promise. In a baffling decision, Wirral Council chose not to extend Rockpoint's tenure of the building, opting instead for the revenue rewards of a hardware store. Hadn't they read the magazine?

The Left Bank idea is an astute piece of positioning, and with an intelligently targeted and resourced campaign, it’s a necessary component in differentiating Wirral's offer, and guiding its regeneration direction. But the Market and Anti-Supermarket case studies also highlight the fragility of mood board-based regeneration, especially when those ineffable and immeasurable subtleties don't convert easily into the hard currency of public sector fiduciary imperatives.

But perhaps there is another flaw in a strategy that fails to distinguish between necessary and sufficient causation. Paris's Left Bank is not simply the bohemian haunts of the Latin Quarter and St Germain-des-Pres and nor is London's South Bank just Borough Market and its trendier residential enclaves. To return to Pat Cleary's challenge, what will make enough people get off the train, or even decide to put down roots in the new urban neighbourhoods envisaged in Birkenhead and the Left Bank? To be more than the One-Eyed town, doesn't Birkenhead need (and deserve) its equivalent of The Musee D'Orsay or Tate Modern? At the conclusion of the Manifesto for Downtown Birkenhead, we posed a question - shouldn't the town that invented public parks and pioneered mass transit reclaim its capacity for innovation and ambition?

“Important places are home to important institutions.... Far from being frightened of big ambitious ideas, we need to encourage them, test them and ultimately deliver them.”

Does 2040 lack the scale of ambition and impact necessary to deliver the catalytic stimulus that Birkenhead requires? Conceiving and delivering projects of that magnitude (including the discreetly mooted V&A of The North) and integrating and re-balancing the two banks of what a casual visitor might mistakenly believe to be one city, is a task that probably necessitated the invention of a City Region and a Metro Mayor.

In fairness to Wirral, the authority has been especially ravaged by the impact of austerity, hollowing out its core capacities and stretching services to breaking point. This is a difficult time to navigate the uncharted terrain of delivery, and the pressure and temptation to find pragmatic compromises may be difficult to resist.

In difficult and demanding circumstances, Wirral has formulated a complex and highly integrated planning and regeneration prospectus, an edifice where big picture objectives are founded on detailed and precisely crafted plans and projects. When Councillors meet to make a final decision on the future of Birkenhead Market in February, they may need to consider whether this is the moment to play a particularly precarious game of jenga?

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

*Main image: Eszter Imrene Virt, Alamy

Mancpool: One Mayor, One Authority, One Vision?

Should the city of Liverpool throw in its lot with Manchester and accept one combined North West Metro Mayor to rule us all? Despite admitting that such a suggestion is about as saleable as a One State Solution for Israel-Palestine, Jon Egan thinks it’s an idea whose time has come. It’s certainly an idea that’s provoked some debate within Liverpolitan Towers. But what do you think?

Jon Egan

Manchester Bees Meet Liverpool Super Lambananas by mmcd studio

Is it time the city of Liverpool threw its lot in with Manchester and accepted one combined North West Metro Mayor to rule us all? Jon Egan thinks so. As you can imagine, the suggestion has caused some debate in Liverpolitan Towers and we are not all in agreement. But what do you think? Here Jon makes his case and hints at future initiatives to come…

So let me issue a warning now. This article contains material that many Liverpudlians will find deeply distressing and offensive. It’s an argument that I have tentatively proffered in the past, but after profound and serious reflection, have concluded, now needs to be set out in the most explicit and uncompromising of terms. You have been warned.

David Lloyd’s recent article for The Post lamenting the exodus of Liverpool’s “best and brightest” was as ever an enlightening and enjoyable read, notwithstanding its downbeat and dispiriting narrative of civic and economic decline. If I can add a generational postscript in support of David’s thesis, every member of our youngest daughter’s friendship group from Bluecoat School now lives and works outside Liverpool.

It was the nineteenth century philosopher, Friedrich Nietzche who argued that only as an “aesthetic phenomenon” does the tragedy of human existence find its eternal justification, and perhaps it’s only in the exquisite prose and imaginative virtuosity of David’s writing that Liverpool’s own tragic predicament becomes philosophically palatable. I admire David’s resolute determination to find some tiny component of hope, offered in the city’s joyously ephemeral hosting of Eurovision 2023. But does our capacity for celebration, hospitality and togetherness provide the alchemy for a viable economic renaissance? Does it, at best, illuminate Liverpool’s status as a half-city, stripped of its economic and productive assets, now reduced to the sheer potentiality of its human capital?

The idea of Liverpool as a stage set for cultural spectacles and entertainment extravaganzas (hyperbolically described by the city’s cultural supremo, Claire McColgan as “moments of absolute global significance”), is a beguiling substitute for an actual economy, and an ability to offer a livelihood for the generations who continue to depart for more attractive and seemingly successful cities. It’s a vision that also reminds me of another of Italo Calvino’s magical realist parables in his masterpiece novel, Invisible Cities. Sophronia, the half-city of roller-coasters, carousels, Ferris wheels and big tops, where it is the banks, factories, ministries and docks that are dismantled, loaded onto trailers and taken away to their next travelling destination.

“I fully grasp the deeply heretical nature of this proposition. A ‘One State’ solution for the Liverpool and Manchester City Regions is about as saleable as a one state solution for Israel and Palestine.”

Two hundred years ago, the realisation that we were a half-city inspired Liverpool’s city fathers to contemplate a project that would have world-changing implications - a genuine moment of “absolute global significance”. Prior to the construction of the world’s first inter-city railway, every human journey between major population centres would be dependent on the locomotive capabilities of the horse. Railways were the harbingers of modernity, compressing time and space, and in this instance, connecting one of the world’s great trading centres with its greatest manufacturing hub. Umbilically conjoined, the two half-cities (the place that trades and the place that makes), became the nexus for Britain’s industrial and imperial prowess for the next hundred years.

If the railway brought Liverpool and Manchester closer together, recent decades have been dominated by a football-terrace inspired antagonism aimed at driving us further apart. Liverpool’s antipathy to our more affluent neighbour would seem also to betray more than a slight hint of jealousy, as our rival has greedily accumulated the trappings and status of regional capital.

Rather than resenting Manchester’s success or investing in a strategy of do-or-die competition, is there a smarter and mutually beneficial alternative? Is it time to re-imagine a more symbiotic relationship, that realises that for every British provincial city, the real competition is located 200 miles to the south?

Of course, this is not an original proposition. In the early noughties, Liverpool Leader, Mike Storey and his Manchester counterpart, Richard Leese signed their much lauded Joint Concordat - an agreement only marginally less shocking than the Molotov-Ribbentrop ‘Non-Aggression’ Pact of 1939 between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. The benefits were equally short lived. The agreement was conceived in the golden age of regionalism when under the aegis of John Prescott’s mega-ministry - the Department for the Environment, Transport and the Regions - levelling-up and rebalancing were not mere meaningless mantras but core political imperatives. For all its good works, the now defunct North West Development Agency, which once employed 500 people to drive the region’s growth, was more of a hindrance than an enabler for a serious rapprochement between the city’s two main economic players. Determined to uphold scrupulous neutrality between Liverpool and Manchester (it’s Warrington-base memorably described by broadcaster and musical impresario Tony Wilson as being located in the “perineum” of the North West), the agency was forged by a powerful Labour Lancashire mafia, with a brief to prevent and constrain the domineering tendencies of the two cities.

The ill-fated 2001 Joint Concordat between Liverpool and Manchester was only marginally more palatable than the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939 which saw the carve up of Poland. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H27337 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

“The idea of Liverpool as a stage set for cultural spectacles and entertainment extravaganzas is a beguiling substitute for an actual economy.”

The Storey-Leese pact conceded Manchester’s status as regional capital, a painful admission of subservience that probably explains the reluctance of subsequent Liverpool leaders to pursue similar overtures. The Liverpool City Region and Greater Manchester devolution deals, and the election of “great mates” Steve Rotheram and Andy Burnham has seen little practical collaboration, beyond occasional media stunts and chummy get-togethers to compare their favourite home-grown pop tunes. Those who expected more than a Northern Variety Hall double act have thus far been disappointed by devolution projects intent on protecting sub-regional domains and denying the compelling reality of geographic and economic interdependence.

We’re two cities less than 30 miles apart, whose fuzzy edges and increasingly footloose populations are blind to civic boundaries that no longer delineate where or how people live, work and play. People are already beginning to see and experience the cities as a single urban place - we just need to dismantle some of the physical and administrative obstacles.

It is beyond farcical that train travel between the two city centres is only marginally quicker today than it was when Stephenson’s Rocket completed its maiden journey two centuries ago. At a pre-MIPIM real estate seminar a few years ago, a Liverpool property professional opined that the single biggest boost to Liverpool’s commercial office market would be a 20 minute train service to Manchester city centre. Who knows, it may even have been enough to persuade Liverpool-nurtured companies like the sports fashion-brand, Castore, to stay in a better connected city location instead of moving to our city neighbour (and taking 300 jobs with it). Questioning the benefits of a fully integrated single strategic transport authority to straddle the two city-regions, is equivalent to advocating the abolition of Transport for London and its replacement by two rival authorities with briefs never to talk to each other.

“Rather than resenting Manchester’s success or investing in a strategy of do-or-die competition, is there a smarter and mutually beneficial alternative?”

For those who ask what’s in it for Manchester, the answer is the well attested and quantifiable benefits of economic agglomeration - cost efficiencies, labour pooling, expanded markets, knowledge spill-overs… Whilst working for the think tank, ResPublica on a project to build the economic case for Liverpool’s connection to HS2, I was staggered to hear Manchester’s economic strategist Mike Emmerich admit that his city envied aspects of Liverpool’s asset-base. The hard and soft criteria by which urban theorists like Saskia Sassen measure the credentials of aspiring global cities, seem evenly dispersed between the twin cities of the Mersey Valley. We can’t match Manchester’s international transport connections, its media and knowledge clusters, but neither can they compete with Liverpool’s global brand, our cultural prowess, architectural grandeur and liveability offer.

If transport is the no-brainer, the wider benefits of agglomeration need to be systematically mapped and identified. The amorphous promise of a Northern Powerhouse can only be realised in physical space, and the contiguity of our two city regions make this the most viable location for a re-balancing project. If the North is ever to grow an economic counter-weight to London, then connecting the two closest jigsaw pieces together seems like a sensible undertaking. Whether its land-use planning or plotting economic development, investment and skills strategies, it’s nonsensical for the two city regions to be pursuing their respective goals in blissful oblivion of what is happening on the other side of an arbitrarily contrived line on a map.

Notwithstanding, its invaluable enabling role in gap funding development and infrastructure projects, the North West Development Agency was a political creation without underpinning logic or legitimacy. Were there ever any connecting threads of economic interest between Salford and Penrith? Wilmslow and Barrow-in-Furness? The Agency’s opaque governance, and its tortuous high-wire balancing act, placating a multiplicity of sub-regional agendas and interest groups, inhibited its ability to optimise the potential of the region’s two great economic engines.

So here comes the controversial bit. Pacts, concordats and convivial personal relationships are simply not sufficient to realise the potential of a new economic relationship between the two city regions - one that acknowledges that their respective asset-bases can be curated for mutual benefit. The only solution is a new governance structure - a devolution model with one Metro Mayor and one Combined Authority. I fully grasp the deeply heretical nature of this proposition, and the threat that it seems to pose to the identity and autonomy of a city that suspects it will be the junior player in any such arrangement. But are identities any more compromised in a ‘Twin City Region’ than they are within the current dispensation? St Helens, Sefton, Wirral, Wigan, Bolton amongst others would probably argue not. The integrity and jurisdiction of the respective city councils and other local authorities would not be compromised - we would only be pooling functions and responsibilities that are already acknowledged to be regional, and projecting them onto a bigger and less artificially contrived regional canvas.

“The only solution is a new governance structure - a devolution model with one Metro Mayor and one Combined Authority.”

Once upon a time, Liverpool and Manchester were authorities under the even more commodious administrative umbrella of Lancashire County Council, and as I‘ve mentioned, more recently, through the North West Development Agency, we were content to buy into the concept of a North West regional project conspicuously lacking any democratic accountability.

In a Twitter / X exchange with Liverpolitan a few weeks ago, I was asked to defend this joint governance proposition by pointing to a successful or established similar model elsewhere in the world. In the US, the twin cities of Minneapolis and St Paul, and of Dallas and Fort Worth, and the urban centres of the San Francisco Bay Area have come together in different ways to pool planning, transportation and economic development responsibilities. Closer to home, the Ruhr Regional Association in Germany exercises both a statutory and enabling role in areas including planning, infrastructure, economic development and environmental protection for the cities of Dortmund, Duisburg, Essen and Bochum. But even if there is no precise template elsewhere, should this be an inhibitor to the cities that built the world’s first inter-city railway, and that pioneered many of the most progressive advances in civic governance in the 19th and early 20th centuries?

In the absence of compelling practical arguments against the proposition, the most likely and persuasive objection will be that the mutual rivalry runs too deep, the antagonism is simply too intense and has festered too long. A ‘One State’ solution for the Liverpool and Manchester City Regions is about as saleable as a one state solution for Israel and Palestine. Maybe it’s an argument that requires a solution or a process rather than a rebuttal. In truth, antipathy is a quite recent addition to a history of rivalry that owes more than a little to the intensity of the competition between the country’s two most successful football teams. Exorcism perhaps requires a practical project, an enthusing collaboration that focuses on shared cultural attributes and ambitions. Somewhere not far away such an idea is maturing, but I will leave it to its progenitors to expand, perhaps on this platform, and maybe very soon.

Of course, there is another motive and spur for this idea which relates to the abject failure of governance within the city of Liverpool and the continuing inability of its dysfunctional political class to nurture or curate those incipient possibilities that so rarely reach fulfilment. The uprooting of Castore from Liverpool to Manchester is an instructive case study, but so too are the games companies, the biotech businesses, legal and insurance firms that have hatched in Liverpool and gone on to prosper elsewhere. Maybe we need governance less rooted in parochial politics and less constrained by cultural legacy. To borrow an analogy from Iain McGilchrist’s Divided Brain hypothesis, perhaps Manchester’s busy-bee utilitarianism and non-conformist pragmatism is the left hemisphere counterpoint to Liverpool’s wistful dreaminess (even our civic emblem is an imaginary being). Is it just possible that our divergent dispositions and outlooks are not actually a prescription for unending antagonism but the formula for a fruitful alchemy?

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Pact! What Pact? An Insider’s View on the Lost Battle to Defeat Labour

In the run-up to the 2023 Local Elections in Liverpool, three men working in the shadows, tried to corral the opposition parties into a pact capable of doing some serious damage to Labour at the polls. But in the face of factional intransigence, personality clashes and party ambitions it was doomed to failure. This is the inside story of that failed mission told by one of those men.

Jon Egan

In the run-up to the 2023 Local Elections in Liverpool, three men working in the shadows, tried to corral the opposition parties into a pact capable of doing some serious damage to Labour at the polls. Described as an exercise in herding cats, the enterprise was ultimately doomed to failure, as factional intransigience, personality clashes and party ambitions took hold, before the electorate then delivered the killing blow. This is the inside story of that failed mission told by one of those men, political consultant, Jon Egan.

“Why are we doing this?” is a question that former BBC Radio Merseyside broadcaster, Liam Fogarty and I have been asking ourselves on and off for more than twenty years.

Even before our involvement in the now largely forgotten Liverpool Democracy Commission, we have been kept up at night wondering how to fix Liverpool's broken civic democracy. Years pumped into a losing battle, the odds very much against us. Have we been wasting our time?

The context for the latest phase of anguished introspection was this year’s local elections in Liverpool which, as you may have noticed, returned Labour to power with an increased majority on the City Council. Before explaining the efforts that Liam, myself and Stephen Yip, a former City Mayor candidate and founder of the charity, KIND, made to avert this seemingly predestined eventuality, it’s worth taking the time to fully comprehend and meditate upon the extraordinary fact of Labour’s victory.

There is no simple or rational explanation for Labour’s achievement, although the campaigning skills of my former Labour Party colleague and strategist, Sheila Murphy need to be duly recognised. The Labour campaign was a brilliantly executed masterclass in misdirection, diversion and manipulation worthy of the illusionist, Derren Brown - wiping the collective memory of the city’s voters and convincing them that their party bore absolutely no responsibility for the endemic chaos, waste, corruption and ineptitude of the last ten years. This election, apparently, had little to do with how a struggling city, effectively governed by colonial administrators, was going to put its house in order. No, it turns out the script was the old familiar one about sending a message to the city's historic arch-nemesis - The Tories.

The result, I suppose, proves precisely how difficult it is for people to overcome addictive and self-harmful habits like voting Labour in Liverpool. Maybe what the city needs is not so much new councillors, but counselling.

‘The Labour campaign was a brilliantly executed masterclass in misdirection, diversion and manipulation worthy of the illusionist, Derren Brown.’

In The Myth of Sisyphus, the writer Albert Camus defined the absurd as the irreconcilable gulf that separates human aspirations from the world’s predisposition to thwart them. The tragic image of Sisyphus struggling to roll his enormous boulder to the top of the hill, already sensing the futility of his labours against the forces of gravity, is an apt metaphor for the investment in time that Liam and myself have made in initiatives, campaigns and conversations undertaken over many years in the hope of making Liverpool’s politics function normally. So if the narrative of this election campaign carries the darkly comic resonances of dramatists, Beckett and Ionesco, and their Theatre of the Absurd, then this is not literary pastiche, but rather the perfect paradigm for Liverpool politics. And in that spirit, it seems appropriate to start not at the beginning, but at the end.

One of the most inexplicable aspects of the election result, was the way that the defeated parties far from despairing at the loss of an historic opportunity, were to varying degrees seemingly satisfied (or at worst only mildly disappointed) with their less than modest achievements. For the Liverpool Community Independents getting only three of their cohort re-elected was at least ‘a springboard’ from which to progress. For Green Party Leader, Tom Crone, “bitter disappointment” extended only as far as lamenting the loss of one target ward (Festival Gardens) by a single vote.

For Richard Kemp, the eminence grise of Liverpool Liberal Democracy, the pitiful addition of three councillors, would give his party “plenty of time for reflection on how the council should work, and where the city should be going.” One wonders how after four decades as a City Councillor, Richard was still trying to figure out these rather elementary conundrums, before he finally decided to fall on his sword and announce his long anticipated retirement as party leader.

So let’s rewind to the beginning, or at least the beginning of Act 2. Act 1 being the heroic, but ultimately doomed campaign by Stephen Yip, to be elected as City Mayor in 2021.

Running a surprisingly close and creditable second to Labour’s Joanne Anderson , Yip’s undoing was the stubborn refusal of Green Party Leader, Tom Crone and the ubiquitous Kemp to stand aside to allow for the possibility of deliverance from a disgraced and discredited Labour administration. The 2021 election seemed, at the time, to be a decisive “never again” moment, with penitential expressions of regret from Liberal Democrats and Greens and pledges to learn the lesson of fractured opposition.

Like trying to roll a rock up a hill. Now more than ever, Liverpool’s opposition parties needed to master the alien vernacular of co-operation.

So to Act 2

Following the publication of the Caller Report in 2021 it was decreed that Liverpool should abandon the baroque and inscrutable election-by-thirds system, and instead adopt an all-out election on new boundaries with the majority of councillors to be elected from single member wards. Now more than ever, Liverpool’s opposition parties needed to master the alien vernacular of co-operation. Seemingly unable to conduct conversations between themselves, the task of scoping the opportunities for an electoral pact fell to myself, Stephen Yip and Liam Fogarty. Having manoeuvred the boulder to within inches (well maybe a couple of hundred metres) of the summit in 2021, we felt that one more effort was something we owed both to ourselves and the people of Liverpool. Far from delivering the new dispensation promised following her election, the era of Anderson 2.0 (Joanne) was notable mainly for its dismal continuity - a botched energy contract costing the city millions, hundreds of millions more written off in uncollected tax and rates, revelations concerning councillors dodging parking fines and extended roles for Government Commissioners taking responsibility for even more substandard and failing services.

The process of encouraging political and electoral co-operation between Liverpool’s opposition factions began with a discrete gathering at Richard Kemp’s house in the summer of last year. Treated to copious quantities of sausages and dips, a generally constructive exchange with Richard and his Lib Dem colleague, Kris Brown, concluded with a suggestion that Liam attend their upcoming policy conference to raise a few issues and provide an outsider perspective on the challenges of the upcoming election. Both from this gathering and the subsequent conference, we sensed a distinct lack of enthusiasm for the idea of any form of electoral pact. If this was to happen, pressure rather than polite persuasion might need to be applied.

By the end of the year, we had started informal conversations with friends and contacts within the other three opposition groups - The Liberal Party (an eccentric relic from the pre-Alliance / Lib Dem era sustained in Liverpool through the hyperactive exertions of its charismatic talisman, Cllr Steve Radford), the Liverpool Community Independents (a party formed by dissenting former Labour councillors primarily disillusioned by cuts and corruption) and the Green Party. With the prospect of another squandered opportunity on the horizon, we resolved to take the decisive step of inviting the leaders to a more formal gathering hosted by Stephen Yip at the HQ of his charity, KIND. The tactical approach was to corral the three most willing participants into an agreement and then publicly challenge or shame the Liberal Democrats to come on board.

‘It began with a discrete gathering at Richard Kemp’s house in the summer of last year, where we were treated to copious quantities of sausages and dips.’

Eschewing sausages for club biscuits (salted caramel flavour), the more business-like ambience of the gathering cut straight to the quick. Without an agreement from opposition parties (all of whom occupied terrain to the left of the centre) we would be facing the prospect of another four years of Labour misrule. Apart from pointing out the mutual benefits of a pact, we offered to provide whatever practical, organisational and campaigning resources we could muster from the networks created during Stephen Yip’s mayoral campaign. Admittedly, these were no match for the Labour legions, but we believed they could help the disparate groups to sharpen core messages, target more efficiently and raise the quality and potency of communication collateral. These resources were conditional on the reality of a pact and a clear indication that its participants were putting city before party.

From the outset the Liberals and Community Independents were fully and unequivocally committed to the principle and practicalities of a pact. For Tom Crone and the Green Party, the proposition was clearly more problematic. Promising to take the idea away for "consideration", we were left with an uneasy sense that history was repeating itself. It was unclear at the time, and indeed still is, by what means of mysterious convocation, the Liverpool Green Party reaches its decisions. With Tom intimating that the national party was instructing them to field the maximum possible number of candidates, the sad implication was that regime change in Liverpool was less of a priority than adhering to the diktat from on high. After several days of radio silence, I was tipped off that Tom would be attending a film event at St Michael's church, and it might be a useful opportunity to see how things were progressing. Our conversation, sadly, revealed that they weren't, and that even a three party pact was becoming an unlikely, if not entirely illusory, possibility.

Stephen Yip's description of our undertaking as an exercise in herding cats was suddenly complicated by the unexpected arrival of a much more exotic species defying all known zoological and political categorisations. The first in a series of audiences with hotelier and property developer, Lawrence Kenwright, took place in late December in the sepulchral gloom of the Alma de Cuba bar, formerly St Peter's church. The bar had been the venue for a series of revivalist-style rallies at which Kenwright had railed against council corruption, presenting himself as the figure-head for a new, popular movement called Liberate Liverpool, that would sweep aside the cliques and cabals that had brought the city to its current parlous state.

‘It was unclear at the time, and indeed still is, by what means of mysterious convocation, the Liverpool Green Party reaches its decisions.’

I was deputed to conduct the initial conversation, that provided a fascinating insight into Kenwright's character and motivation, the history of his relationship with the City Council and Mayor Joe Anderson, and the ambitions underpinning his political project. Kenwright's almost visceral determination to unseat Labour was evident; what was less clear was his precise role in the project, and the means and method by which it was to be achieved.

Whilst it was easy to understand the motivations behind Liberate Liverpool, and its attraction as an antidote to an out of touch and self-serving politics, it was difficult to believe that it offered any kind of remedy. Symptoms are not cures, and Liberate Liverpool’s attraction for cranks, conspiracists and far-right interlopers was perhaps an inevitable consequence of its febrile genesis and almost millenarian rhetoric. Some good and sincere people answered the call only to be sent into battle with the campaigning equivalent of peashooters and water pistols. At a subsequent meeting (accompanied this time by Liam Fogarty and ex-Labour Councillor Maria Toolan), we embarked on what we thought was a subtle policy of dissuasion, politely pointing out the inherent flaws of a campaign targeting "people who don't vote" and relying almost exclusively on social media, only to be accused by a Kenwright acolyte of "disrespecting Lawrence."

Our approaches were an attempt to scope the albeit remote possibility of identifying suitably vetted independent candidates who could be assumed into a broader-based Clean-Up Coalition. It is an indicator of our desperation that this hope was ever entertained.

‘We embarked on a subtle policy of dissuasion, politely pointing out the inherent flaws of a campaign targeting "people who don't vote" only to be accused by a Kenwright acolyte of "disrespecting Lawrence."'

As February rolled into March, our efforts became simultaneously more modest and more desperate. Following advice from a sympathetic insider, we were advised to bypass Kemp and re-pitch the idea of an electoral pact to the Lib Dems through the party's former leader and campaign supremo, Lord Mike Storey, who we later discovered was to stand as a candidate in Childwall. Alas Stephen Yip’s conversation with Storey was even more emphatically negative than the sausage-gate soiree with Kemp months earlier.

It was clear we needed to explore more pragmatic alternatives. If not a city-wide pact, perhaps a nod and a wink understanding to avoid actively campaigning in each other's target seats? Maybe also an agreement around some core commitments to improve transparency and accountability, combat corruption and restore public confidence in the City Council? Initially, Richard Kemp sounded refreshingly and surprisingly up for it, but with the fatal complication that some of their target seats were also target seats for the Greens and the Liberals. Nods and winks would have to be restricted to the safest Labour seats in Liverpool where none of the opposition parties entertained serious hopes of winning. In other words, for show only. Meanwhile, Stephen Yip drafted four pledges on transparency and corruption, which were immediately endorsed by the Community Independents and the Liberal Party. The Lib Dems, however, would not sign up; the response published on the But What Does Richard Kemp Think? blog, a depressingly patronising and public epistle "explaining" that the proposals were either illegal, already in place (due largely to his efforts) or would be a waste of money. It seemed futile to point out to Kemp that the proposal for an Independently-chaired Standards Board was not only perfectly lawful, but had been initially drafted for Stephen's Yip’s 2021 manifesto by Howard Winik, who was now a Liberal Democrat candidate.

Unlike his predecessor, does the Lib Dem’s new leader, Carl Cashman have the imagination or inclination to detach his party from its comfortable civic niche in South Liverpool suburbia?

For me, this was perhaps the final and conclusive evidence that laid bare the true nature of Liverpool Liberal Democrats and their deep complicity in a council whose corrupting and dysfunctional culture long predates the shortcomings of the Joe Anderson era. They are not, in my view, an "Opposition Party" in any meaningful sense of the word, but are more akin to the tame collaborators in the sham democracies of the Soviet Bloc - the Liverpool equivalent of the Democratic Farmers Party of East Germany. They have no desire to fundamentally reform or reset a moribund civic culture, but are content to bide their time in the hope that circumstances will grant them an opportunity to preside over its decrepit edifice. In one sense, Liberate Liverpool were right; the Liberal Democrats are not part of a solution, but are an intrinsic and intractable part of the problem. Whether Kemp’s much younger successor, the neophyte Carl Cashman, has the imagination or inclination to detach his party from its comfortable civic niche and the bucolic pastures of South Liverpool suburbia, will largely determine whether Liverpool's local democracy remains a hollow charade, or becomes an empowering mechanism for change.

‘The Lib Dems are not an "Opposition Party" in any meaningful sense of the word, but are more akin to the tame collaborators in the sham democracies of the Soviet Bloc - the Liverpool equivalent of the Democratic Farmers Party of East Germany.’

Epilogue

It is the tragic-comic circularity of the narrative that makes Liverpool politics an absurdist drama. The interminable wait for Godot - an intervention, a new structure, a new political alignment, a salvific figure able to break the cycle of failure, corruption and chaos that has blighted our city for as long as anyone can remember.

On the day of polling, I was helping Maria Toolan with some last minute door knocking to encourage supporters to get out and vote in the City Centre North ward. She was already sensing with fatalist resignation, that her efforts to unseat two former Labour colleagues had failed. "The problem is," she lamented "people aren't bothered about waste and corruption, it's what they expect from the city council and they don't believe that it's ever going to change."

This is the suffocating dead weight of Liverpool politics, an oppressive inertia and sense of fatalism engendered by decades of broken promises, betrayed trust and shameful failure. It's the gravitational drag that immobilises progress and snuffs out any glimmer of a more honest and hopeful politics.

Labour's strategy understands and exploits this endemic cynicism. It doesn't really matter how badly we've governed Liverpool, this is a Labour city and elections cannot alter this brute existential reality. Sending a message to the Tories might actually seem like a more worthwhile place to put an ‘X’ than investing in a hope for something better, when you suspect that this isn't even a logical possibility. Little wonder that 8 out of 10 Liverpool voters decided to stay at home.

Would an electoral pact have unseated Labour? Would it have signalled to voters that there was a tangible possibility of an alternative administration? It's hard to say, but looking at the results and totting up the number of seats where competing opposition parties on the progressive wing of politics won more votes than the Labour majority, it cannot be completely discounted.

Labour mis-fire. By personalising the campaign against Gorst, they had also localised it. In Garston, the election was no longer a rehearsal for a General Election. It was about the honesty and integrity of individuals and their credentials to represent their community - weak territory for Labour to fight on. Photo from Twitter @Pablo8485

If there is cause for hope, it was in the response to what was one of the most deplorable manifestations of Liverpool Labour's darker instincts. The officially sanctioned Labour campaign, scripted from on-high and professionally disseminated under the supervision of Sheila Murphy and their Regional Office, was a vacuous mash-up of kick-the-Tories and Eurovision-phoria. But beneath the sanitised veneer another more vicious and toxic campaign was being waged against Community Independent candidates who had originally been elected under Labour colours. Fake social media accounts became platforms to abuse, ridicule and defame the Community Independents with particular venom aimed at Sam Gorst, a former Labour Councillor seeking re-election in Garston.

The ferocity of the campaign against Gorst reached its nadir with a shamefully deceptive leaflet masquerading as a community newsletter which raked up Gorst's old social media posts, and more seriously, falsely implied that he had used his position as a councillor to jump the social housing queue. Within an hour of the leaflet being issued, we launched our final, and perhaps only effective contribution to the election campaign. A round-robin email was despatched to secure the support of the city's four opposition leaders in a joint denunciation of Labour's malicious and dishonest leaflet. And to their credit, Kemp, Radford, Crone and the Community Independent's Leader, Alan Gibbons all replied with personalised quotes for a media release within 30 minutes. The unprecedented show of unity secured positive media coverage, that was followed by The Echo's political correspondent, Liam Thorp exposing the tell-tale fingerprints of Labour on the scurrilous social media accounts.

An otherwise faultless Labour campaign had slipped up. By personalising the campaign against Gorst and his running mate Lucy Williams, they had also localised it. This election and the campaign against Alan Gibbons in Orrell Park, were no longer just dummy run rehearsals for a General Election or a vote of thanks for delivering Eurovision; they were about the honesty and integrity of individuals and their credentials to represent their community. Gorst, Williams and Gibbons' victories may or may not be a platform for the future growth of the Liverpool Community Independents Party, but they are perhaps a hopeful intimation that gravity doesn't always win.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Eurovision 2023: Liverpool’s Imperfect Pitch

When Liverpool won the right to host Eurovision 2023 on behalf of war-torn Ukraine, most people in the city celebrated. With its reputation for music and for fun nights out, allied to its compassionate heart, the city was seen as the perfect fit in difficult times. But some have warned that in mistaking kitsch for cool Liverpool risks reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of its cultural brand. Jon Egan wonders how we can subvert expectations to deliver on the European Song Contest’s higher purpose.

Jon Egan

Amidst the near-universal jubilation at Liverpool’s successful bid to stage Eurovision, I struggled to suppress an almost inchoate feeling of dissident cynicism. Is the European Capital of Culture now pitching its future identity on an ambition to be the European Capital of Light Entertainment?