Recent features

Israel-Hamas: Britain looks for fascists in the wrong place

In the wake of the Israel-Hamas war, Pro-Palestinian marches calling for a ‘Ceasefire Now’ are attracting ever larger crowds in Britain’s cities. But with the reaction comes a counter-reaction. Are fears that the Far-Right will exploit these tensions to sow mayhem truly justified? Or could it be said that those calling for peace are turning a blind eye to the support for fascism within Hamas and the Free Palestine movement?

Paul Bryan

It was like all their Christmases had come at once. This was the evidence they needed to quash their opponents and get rid of that evil witch, Suella Braverman, the now ex-Home Secretary.

Famed Far-Right pantomime villain, Tommy Robinson had put in a brief London appearance on Armistice Day as part of the counter protest against the Pro-Palestine march, though he quickly fled the scene in a taxi once the police closed in. There was some pushing and shoving and objects thrown as a crowd of white men headed to ‘protect’ the Cenotaph. “Every. Single. One. Of. Them. Was. Looking. For. Blood. Every one,” intoned professional scouser, sports reporter and mind reader Tony Evans, formerly of the Times. After all, he should know. “I live in Pimlico,” he tweeted. Enough said.

The media went to town of course, with Channel 4 News embarrassing themselves with the claim that ‘the only scuffles on the day involved far-right protesters who clashed with police.’ This spurious claim was later deleted.

Meanwhile, that bellwether of over-the-top reaction, polemicist Owen Jones, did his level best to impose a simplistic division of oppressed and oppressor on the marches. “There were two protests,” he tweeted. “One were a bunch of far right thugs intent on violence. The other was a massive Palestinian protest with “no issues”. One was whipped up by politicians and media outlets. The other was demonised by them.” At least Owen, waited for events to unfold (somewhat). The Liverpool Echo’s political editor and sometime Newsnight guest, Liam Thorp, couldn’t wait to get stuck in, tweeting at 11am that “The responsibility for any violence today lies solely with the Home Secretary and the Prime Minister who is too weak to deal with her dangerous chaos.” Why does he always sound like a pound-shop Churchill?

The feeling that the script was already written before the birds had tweeted was overwhelming. So let’s get somethings straight. Members of the Far Right were present in London though their numbers are hard to pin down – I’ve seen everything from 200 to 2000 quoted in the media – a x10 level of confusion that points to the subjective nature of the assessment. Quite what qualifies which members of the crowd were Far Right and which weren’t was not always obvious – though white skin, opposition to the Pro-Palestinian marches and shouting obscenities seemed qualification enough for many pundits. I suspect membership cards of the English Defence League and their like were largely absent but who knows? After all, the Far-Right label is used so promiscuously these days, it’s becoming hard to distinguish between your Mosely’s and your Monetarists. Alan Gibbons, leader of the Liverpool Community Independents seemed to sum up the mood of presumption - “Look, if it quacks like a fascist, chants like a fascist and attacks police like a fascist it's a fascist.” Obviously not spent much time around Red Action then. Anyway, Alan thought he’d found the smoking gun – a picture of a thug with a swastika tattooed on his torso. Labour MP Dianne Abbot was chuffed about it too. Sadly, a quick reverse image search revealed the picture was from 2016 and not in fact from this year’s Armistice Day marches, but let’s not allow facts to get in the way of good story.

Talking of facts, here’s a few – 126 people have so far been arrested in a demonstration involving over 300,000 people. More will most probably follow but the number is thankfully relatively small. Many of those arrests, as one officer explained on the radio, were pre-emptive of serious trouble, the police choosing to use arrests as a method of keeping opposing camps apart. A knife, a knuckleduster and a baton were found as well as some class-A drugs. Nine police officers were injured amidst chants of “You’re not English anymore.”

We’re told the majority of arrests were from the right-wing and according to the Metropolitan Police Assistant Commissioner, Matt Twist this group was largely made up of “football hooligans from across the UK.” The police are now trying to hunt down protesters from the pro-Palestinian side who are accused of that most amorphous of crime/non-crime categories - hate crime, as well as possible support for proscribed organisations like Hamas. Officers intercepted a group of 150 who were wearing face coverings and firing fireworks. Arrests were made after some of the fireworks struck officers in the face.

So there you have it. It got ugly in places, and where it did the police successfully kept a lid on things. But and here’s the rub, I’m struggling to reconcile the relatively small scale of the trouble with the histrionic shout-outs for a disaster averted. The question we should ask ourselves is why were the ‘Ceasefire Now’ crew so excited about the appearance of a scintilla of right-wingers?

“The idea that white, Far-Right nationalists were just waiting for their Asian Home Secretary to let them off the leash is of course absurd.”

I think there are two answers to this question. One is about Suella Braverman and the other is about diverting the public gaze from the horrors of Palestinian violence.

On the first point, LBC presenter James O’Brien, who likes a good quote, couldn’t help giving the game away. “The Home secretary wanted a riot,” he thundered. Does he do anything but thunder? He continued… “Editors of national newspapers, columnists and commentators… ‘pray that there is not a riot at the Cenataph’ they wrote, while licking their lips at the prospect.” Oh, the hypocrisy! It should be clear to everyone that Suella Braverman is everything progressives hate. They were determined to pin this one on her because they wanted her head and they weren’t going to be satisfied until they got it. Right wing violence on Armistice Day was the metaphorical bullet and they were determined to pull the trigger.

I just wish the James O’Brien’s and the Liam Thorp’s of this world would be honest about that – they were licking their lips too. The absurdity of the proposition that it was all Suella’s fault was for me, best summarised by this tweet…

‘Seen the latest from Suella lads? Worth the subscription to get over the Times paywall. Also excellent pieces from Caitlin Moran and Giles Coren, and Eleanor Hayward is simply the best health correspondent in Fleet Street,’ wrote Gareth Roberts.

The idea that white, Far-Right nationalists were just waiting for their Asian Home Secretary to let them off the leash is of course absurd. But it reveals how the public is increasingly viewed by the political class as mindless puppets who will do whatever they’re told. If it wasn’t for Suella, the logic goes, the yobs would have stayed at home, ironing their flags of St George. They were ‘inflamed’ by her words, unleashing the beast within. As if.

The other reason for the lip-licking is all too transparent. It’s the finger pointing of the anti-racist. ‘Look’, they say, ‘only racists and white supremacists would not want to join our side in our quest for a Free Palestine. Israel is an apartheid state. Join us, as we march from the river to the sea.’

“For all the focus on the threat of Britain’s rump of a right-wing and their historic focus on immigration and racial purity, do you not see a far more extreme mirror of that vile ideology in the rantings of Hamas and Hezbollah?”

These tactics are destined to fail because there are many who can see through them and don’t want to become apologists for a form of Islamofascism. Yasser Arafat, the one-time Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and leader of the supposedly more tolerant Fatah Party, once said, “We will not bend or fail until the blood of every last Jew from the youngest child to the oldest elder is spilt to redeem our land.” What do you think he meant exactly? For all the focus on the threat of Britain’s rump of a right-wing and their historic focus on immigration and racial purity, do you not see a far more extreme mirror of that vile ideology in the rantings of Hamas and Hezbollah? Except, unlike the EDL, these ‘liberators’ have the weapons and the resources to kidnap, maim and kill, as well as making victims of their own people.

Calling for a Ceasefire Now means leaving Hamas intact, free to pursue future campaigns of horrific barbarism. More October 7ths. No thank you. Not for me.

Israel-Hamas: Collective insanity threatens to overwhelm us

In the aftermath of the Pro-Palestine marches in London and the much smaller counter-protest, a game of political ping-pong has ensued. Videos clips are being swapped online from all sides as a new digital currency in moral certainty. Have you seen the one of fascists surging past the police? Yobs! Right-wing scum. Yes, but have YOU seen the one with the Palestine supporter saying, “Hitler knew how to deal with these people.” Islamic fascism right there. Yes, but what about those WHITE supremacists causing mayhem at the train station? What, you mean the one where a protester shouts “death to all Jews.” And so it goes on…

There’s a danger that we’re all about to lose our heads and if we let it, it could get ugly.

Now, I don’t want to give the impression that this is about to be some country vicar, Thought For The Day style piece, urging a gentle middle road, while papering over the cracks in our civilisation with kind words and a cup of tea. There is clearly a huge amount at stake. But I would at least ask everyone to take a deep breath and not assume the very worst motivations from those who find themselves on the opposite side of the fence. There lies the path to de-humanisation and all that goes with it. Rather than summoning partial evidence to prove a point that we know deep down does not represent the full picture, maybe we should look for the courage to acknowledge the flaws in both camps.

Is this image dehumanising? Owen Jones thought so but others disagreed. If we are forever re-defining words to mean whatever we want them to mean, we will lose our ability to think straight. Perhaps that’s the point. Image: Twitter; cartoon originally from Ramirez, Las Vegas Review Journal for the Washington Post.

I for one am critical of the Pro-Palestinian ‘peace’ marches. I just don’t think they represent what their supporters claim, hopelessly entwinned as they are with Islamicist influences favouring a free Palestine ‘from the river to the sea’. A recent article in the Telegraph showed six of the organisations behind Saturday’s London march had connections to Hamas including Muhammad Kathem Sawalha, a former Hamas chief who co-founded the Muslim Association of Britain. This is not a good look. To me, too many people are diving naively in with their eyes closed to the movement’s nasty antisemitic underbelly and risk turning themselves into willing tools of groups who do not share their values and who use apologists consciously and calculatingly as cover. But even I have to admit that many of the protesters clearly mean well – responding to the horrific pictures coming out of Gaza with a natural, empathic desire to put a stop to the suffering. Clearly, they hope that silencing the guns can be a first step in finding a new and lasting peace process in which all can reconcile and heal deep wounds. This is an admirable instinct and should be recognised (when it’s not premised on virtue signalling), but I’d put it in the category of viewing the world through the lens of how we want it to be, rather than how it is really is.

Palestinian leadership have rejected every peace offer that’s ever been put on the table – in 1947, in 2000, and 2008. Negotiations have swiftly been followed by rockets and bombs. Meanwhile, the Jewish settler movement, aided with a nod and a wink by the administrations of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, appears to believe it is their God-given right to continue encroaching on the West Bank. As one settler infamously explained a few years back, while attempting to take possession of a property that wasn’t his, “If I don’t steal it, someone else is gonna steal it.” This is religiously inspired entitlement as cover for our basest instincts.

A prized peace cannot hold in the iron grip of absolutism. For all the blood and rubble, you cannot negotiate with someone whose only vision of the future is wanting you dead and gone. Especially ones with a scripture-endorsed death wish where, as author and podcaster, Sam Harris puts it, sadism is “celebrated as a religious sacrament.” Those who have watched the raw footage of the October 7th massacre have described how the killers were elated at their deeds. Douglas Murray for the Jewish Chronicle recounts chillingly, how one Hamas terrorist called his parents back in Gaza to boast that he had killed ten Jews “with my own hands.” Ecstatic with joy he received the praise he desired - “Their boy had turned out good.”

“A prized peace cannot hold in the iron grip of absolutism. For all the blood and rubble, you cannot negotiate with someone whose only vision of the future is wanting you dead and gone.”

There is a secularist presumption at play that all people basically want the same thing – peace, security, a roof over their head, good schools, full bellies and a decent job. But what if it’s not true? Here in the West, this ‘humanistic’ presumption is mapped onto the Israel-Hamas conflict even if it doesn’t apply to all the protagonists. People calling for a ceasefire now, such as the RMT union leader, Mick Lynch end up thinking with a bit of good grace and a fair wind the Israelis and Palestinians can be convinced to sit around a table and hammer it out. As if this was a negotiation over terms and conditions. From this perspective, when confronted with the reality of suicide bombers and hideous acts of barbarity, the question is asked - how could this be? What could turn people to such extreme behaviour? And the prescription as Sam Harris characterises it, is always the same – “they must have been pushed into it…their entire society oppressed and humiliated to the point of madness by some malign power. So many people, he says, “imagine that the ghoulish history of Palestinian terrorism simply indicates how profound the injustice has been on the Israeli side.” And some might argue that the extremities of the Jewish holocaust layered on century after century of cruel pogroms have had a similar effect on the Jewish psyche. But perhaps these explanations are all too neatly packaged for the contemporary western imagination. In an interview with Piers Morgan, psychologist and author, Jordan Peterson makes the point that the sins of the father are visited on their children. That we may not wish life was like this, but it is – generations of bloody violence echoing down in retribution. It’s hard to break the cycle, not impossible, but hard, especially when you add a strong dose of religious certainty that can make even good people do bad things.

Maybe, just maybe, the cries to martyrdom reveal a deeper, unsettling truth about the role belief plays in violence. Maybe the people of the region need to look deep within to question the core ideas that shape their coda.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor and creative coach.

@thePabryan

*Main image: Mark Kerrison, Alamy

Ye Wha? Opera on the Mersey and other Mad Visions

For over ten years, 3D animator Michael McDonough, has been dreaming up new ways to re-imagine Liverpool’s urban landscape – designing outlandish opera houses, cathedral-like train stations, gothic bridges, and new visions for the docks. None of them have been built or are ever likely to be. But why does he bother? In this showcase of his work, Liverpolitan Editor, Paul Bryan explores Michael’s fascinating dreamscapes of the imagination.

Paul Bryan

“The way I come at things is to make no small plans. The city has had too much of that, too much dross, too much crap, too much small time thinking.”

So says Michael McDonough, Co-Founder here at Liverpolitan, and a man who has developed a bit of a reputation for his outspoken criticism of Liverpool’s (lack of) development scene. And in fairness, it’s a view that I, as the magazine’s Editor, often share.

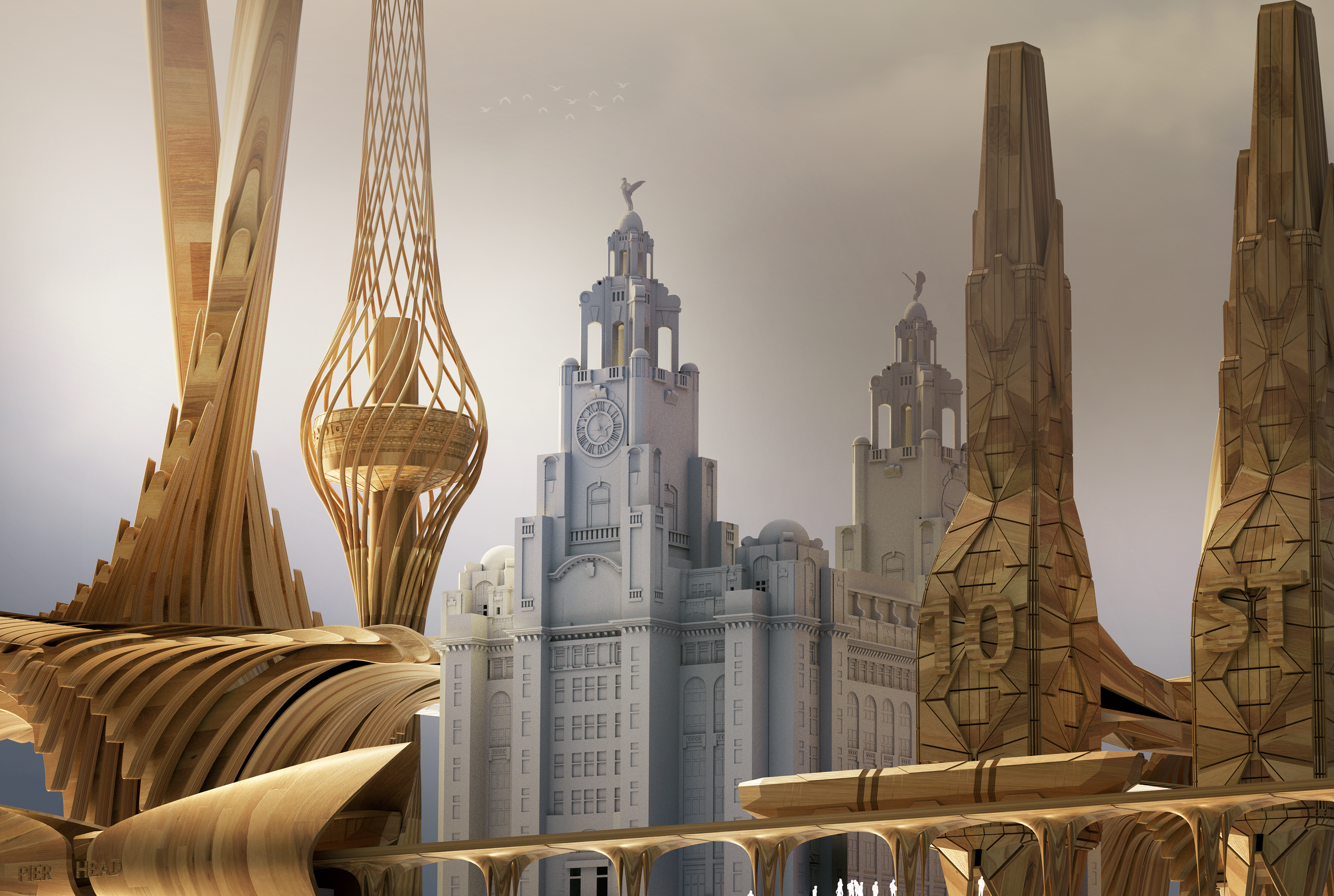

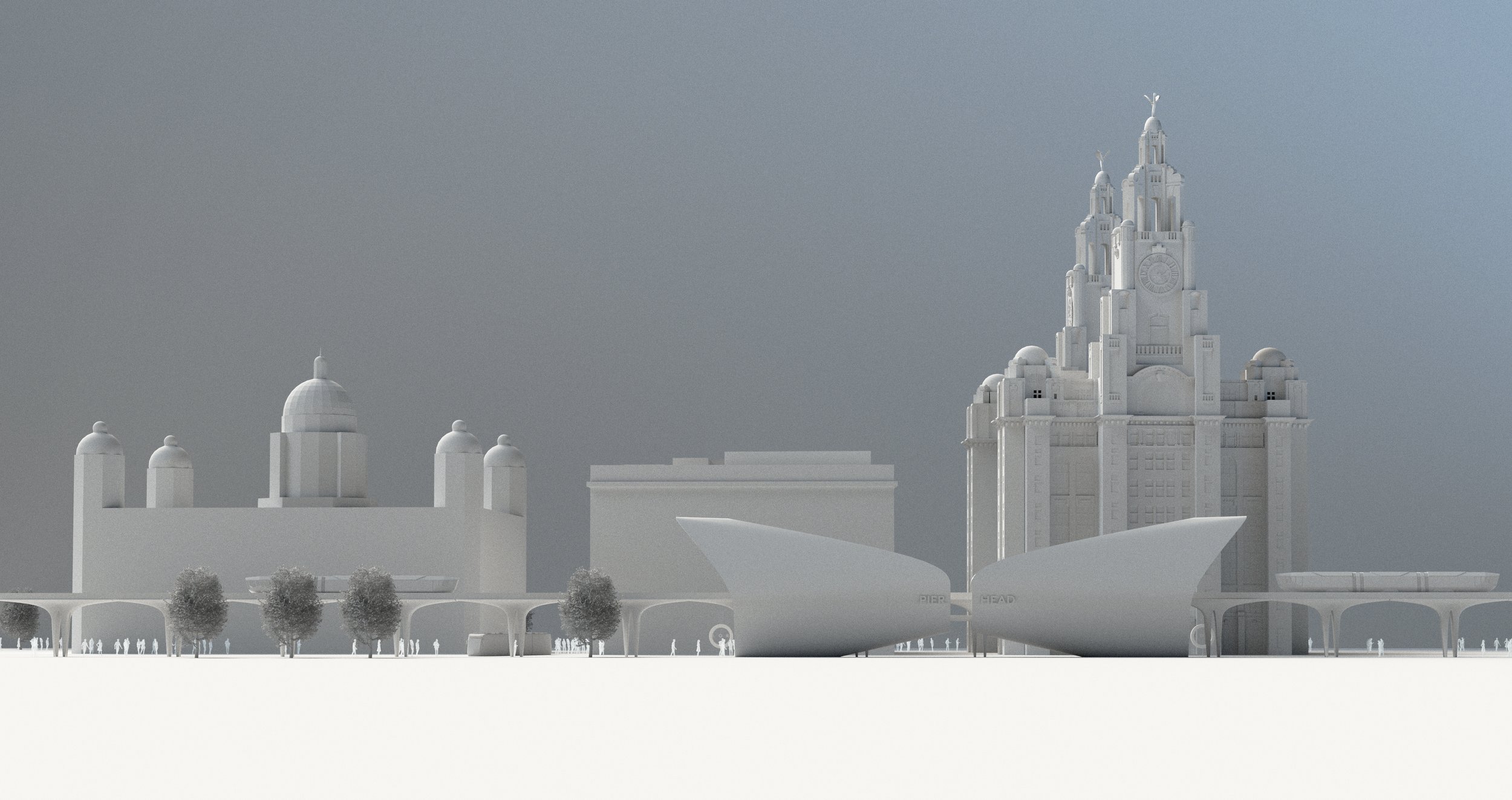

One of the things that makes Michael interesting to me (other than the fact he’s had to develop skin as thick as a rhinosaurus to bat off ‘the army of gobshites’ who take him on or even pose as him online) is the fact that despite a successful career as a 3D designer and animator which has taken him to the capital, he continues through his design work to try to make a positive contribution to his home city of Liverpool and the discussion about its future. He does this without fanfare or gratitude and in fact, often in the face of quite complacent criticism from ‘locals’. Often by people with far less talent or insight than himself. For over ten years now, entirely under his own steam, Michael has been dreaming up new ways to re-imagine Liverpool’s urban landscape – designing outlandish opera houses, cathedral-like train stations, gothic bridges, and new visions for the docks. None of them have been built or are ever likely to be. They are not fully formed architectural plans, more dreamscapes of the imagination and we’ve made a showcase of that work in this feature article.

But why does he bother? What’s the point? Aren’t they just castles in the air built before AI and Midjourney made fantastical images the prerogative of all? To believe so would be to miss what’s really going on. There’s a much harder edge lying beneath the glossy visuals. He’s making the case for ambition as an antidote to a city-wide loss of nerve.

“We should be thinking in the same way world cities do like London, Singapore and New York. All these places have big ambitions. We should be looking to emulate that,” says McDonough. Instead, he believes Liverpool increasingly seems resigned to a lower status and too often its mediocre plans reflect that. Small schemes are favoured over transformative ones and then heralded as being the way forward. Anything substantial or showy is typically treated with hostility and suspicion.

“I keep hearing that in Liverpool we’re different, that we have our own models of success, but it’s a language of defeatism, masked and airbrushed as some kind of urban superiority.” He rejects this idea totally. “Being different doesn’t mean you reject ambition, scale and big ideas. That doesn’t make you different, it just makes you stupid.”

‘There’s an obsession in Liverpool’s planning circles with ‘context’ – the idea that new developments must be submissive to the city’s crown jewels."

Michael’s designs are meant in sharp contrast to the veritable cottage industry of ‘place-making’ peddlers, much favoured in recent years by our city leaders, whose low aspiration output chimes with this defeatist mindset. Meanwhile, the same old local architectural practices win job after job, churning out budget off-the-shelf buildings that further erode what makes the city special. There’s an obsession in Liverpool’s planning circles with ‘context’ – the idea that new developments must be submissive to the city’s crown jewels. But that attitude just results in bad buildings and Michael’s designs deliberately shun such restrictions. Some of his designs will inspire, but also enrage.

“The irony,” says McDonough, “is that those buildings we love so much are there purely because of ambition, because of power and commerce. They didn’t just land there as gifts from God.”

The point of history is to learn from it, not to fetishize it. We do Liverpool’s history a disservice by feeble attempts at mimicry. The Liverpool of yesteryear was bolder and more global in its perspective and if we are to take something useful from the past, it should be that. What Michael is attempting to do with these designs is to remind the city that it’s capable of bigger ideas, capable of re-imagining itself, capable of statement architecture, and capable of challenging its city rivals.

“What pushes me to create these designs is a desire to make people see the city differently – and by that I mean primarily the people who live and work within it. Because if we can awaken that boldness of old, so much is possible in our future,” says Michael. That is the lens through which he’d like people to view his designs. Of course, design is subjective. What might be considered beautiful by one person, can be viewed as horrendous by another but he claims to welcome those reactions. “One of our motivations for founding Liverpolitan magazine, was to create a place where thoughts and ideas on the city’s built environment could be shared, discussed and visualised – to think beyond self-constrained limitations,” he concludes. And indeed that is part of our mission.

So buckle in. This is Michael’s contribution. We hope others will be inspired to contribute in the future. It’s a long read. You may need a cup of tea. But there are lots of pretty pictures and food for thought.

Enjoy.

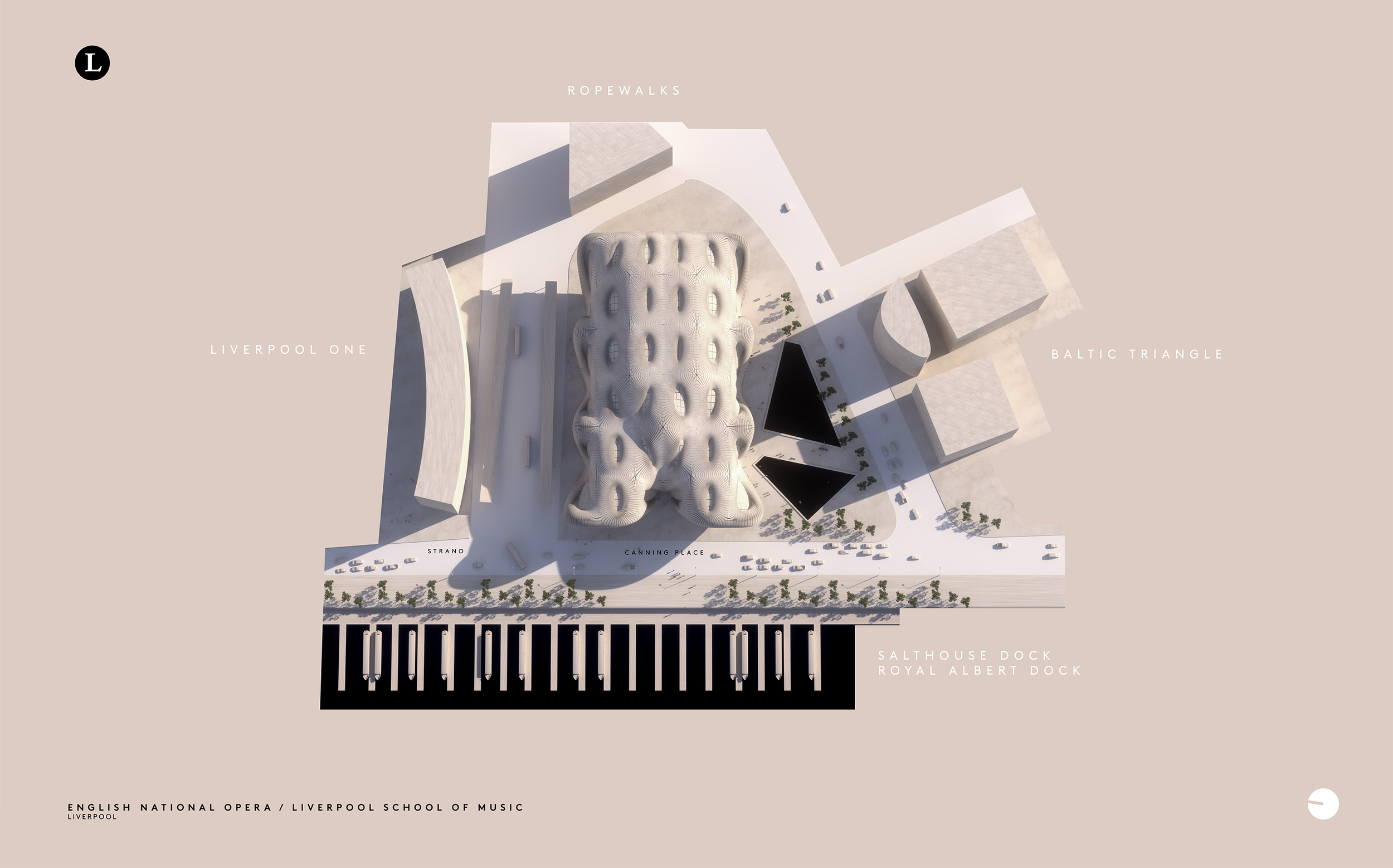

English National Opera, Liverpool

Post-Eurovision, Liverpool emerges with its reputation for hosting big events enhanced and attention inevitably turns to ‘what next?’ So how should the city attempt to capitalise on this positive exposure? Capitalise being the key word here – turning the benefits of a one-off event into something long-lasting, and preferably given a tangible physical form.

Step forward candidate 1: The English National Opera (ENO). This prestigious London-based institution has been told by its funders, Arts Council England, that if it wants the purse strings to remain untied, the institution needs to up-sticks and move to the regions, and rumour has it that Liverpool is very much on the short-list. Some will question why a city like Liverpool needs opera, but even if Tosca and Turandot are not your kind of thing, attracting such a high profile organisation will only add to Liverpool’s cultural offer and open up new job opportunities for young people who might otherwise fly the nest.

Dreaming up a new opera house on the banks of the Mersey, is something that dates back to the wild and unfunded dreams of former Mayor Joe Anderson. But this time, at least in theory, the prospect sounds a little more plausible. Not fully plausible mind – a recent article in The Post claimed the move might be more northern outpost than wholesale relocation, akin to Channel 4’s setup in Leeds. Still, it’s not completely out of the equation – especially if a new facility could combine uses with other functions – education, meeting space, performance arts. Back in 2021, the then-chancellor, Rishi Sunak allocated £2m for a feasibility study into some kind of new immersive music attraction. So despite initial talk of yet another Beatles-focused space, perhaps there’s scope for blending these projects onto one site to make the whole more achievable.

‘The point of history is to learn from it, not to fetishize it. We do Liverpool’s history a disservice by feeble attempts at mimicry.’

The most obvious location is the site of the now defunct former police station headquarters at Canning Place off the Strand. It’s a big site in a glamorous location with the potential to integrate the city centre more closely with the Baltic Triangle. In scale, Michael is proposing a building similar to the much lauded Copenhagen Opera House, which also has a waterfront setting, but he’s keen to avoid any slavish adherence to ‘context’ – “the space is big enough to create its own”, adding new aesthetic design cues to Liverpool’s urban environment rather than forever replicating (usually in impoverished form) what is already there. For Michael, this means “no warehouse-style blocks, no red-brick, and a departure from straight lines.” Some have said they can see a cobra snake in this design and others an elephant (hopefully not of the white variety). “I didn’t intend either but if they’re there, they’re there,” says Michael. “It’s all about organic, smooth, natural forms.” The final two images in the set, which show the interior of the main auditorium, were created using artificial intelligence more as an experiment in what is possible with the technology.

As an added bonus, Michael is proposing to demolish the John Lewis car park, which adds a “blocky barrier to the growth of the city centre eastwards,” as well as eroding the sense of occasion that this landmark structure deserves. A new solution would have to be found for the bus depot that sits beneath it (not to be confused with the Paradise Street Bus Station which would remain unaffected).

Liverpool Overhead Railway

Many people have long been fascinated by the Liverpool Overhead railway and perplexed by its loss. Extending seven miles along the length of the city’s impressive docklands from Seaforth and Litherland in the north to the Dingle in the south, the line survived for just 64 years before the decline in dock employment ate too deeply into its commuter base. There can be little doubt that if the Overhead Railway had survived into the modern era instead of being dismantled in 1956-57, it would have become another iconic symbol of Liverpool reminiscent of the Chicago ‘L’ trains. Not only that, but it may have long ago expedited the regeneration of the north docks into other uses. Instead, minus viable transport provision, we have had to watch on powerless as docks have lain derelict for decades under the tattered banner of Liverpool Waters.

As much as it’s fun to sit within an old Overhead carriage within the Liverpool Museum (and marvel at its spacious dimensions and varnished wooden interiors), Michael would much prefer to see it rebuilt. The case is becoming stronger with the soon to open Bramley Moore Dock Stadium, the Titanic Hotel and new apartments in the Tobacco warehouse extending the city centre and creating a line of activity to the attractions centred around the Albert Dock.

‘The Liverpool Overhead Railway may have long ago expedited the regeneration of the north docks into other uses. Instead, minus viable transport provision, we have had to watch on powerless as docks have lain derelict for decades under the tattered banner of Liverpool Waters.’

However, Michael says “we cannot and should not merely recreate a pastiche of the old line.” Technology and engineering have moved on, and the old structure was difficult and expensive to maintain. Besides, its heavy-set viaducts blocked views of the river from further inland, which might be unwelcome today. If the city are ever to rebuild the Liverpool Overhead Railway, he feels it should “celebrate the past but not be beholden to it.” A little like London’s Docklands Light Railway (DLR), his version 2.0 is a fully-fledged railway, not a monorail, elevated by organic and elegant concrete columns that avoid the blocky and very nineties form of the DLR design.

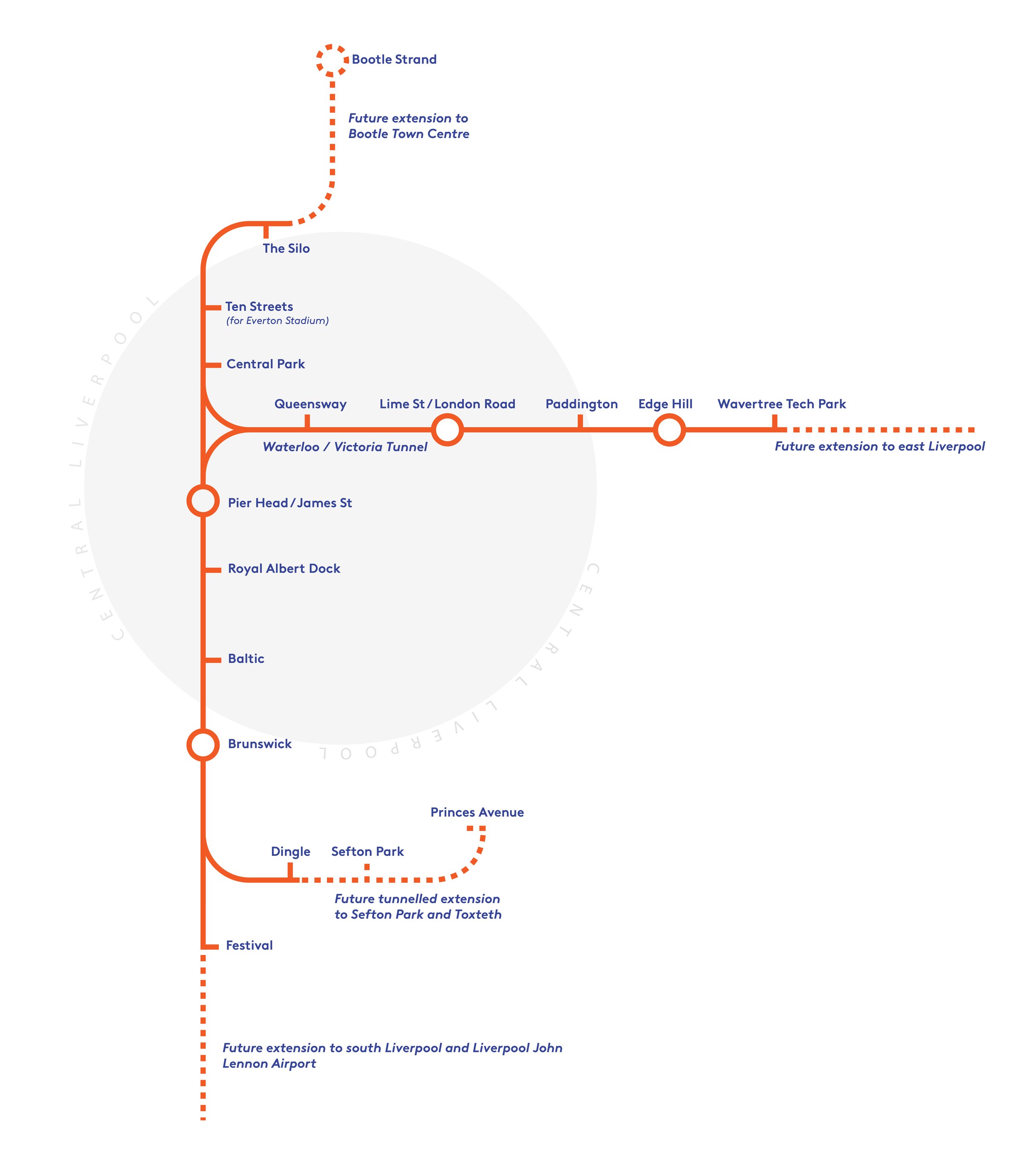

To maximise its utility, Michael’s new Liverpool Overhead Railway would not simply follow the old route but would connect more widely. Starting at Bootle in the north to better integrate that area as part of our metropolis, the line would connect the Everton stadium and key attractions centred around the Albert Dock before heading off south to the airport, and perhaps also east via the disused Waterloo or Victoria tunnels. The design of the structure would be modern, and the trains capable of running on conventional tracks (like the recently introduced Merseyrail ones) opening up options for integration with the wider rail network.

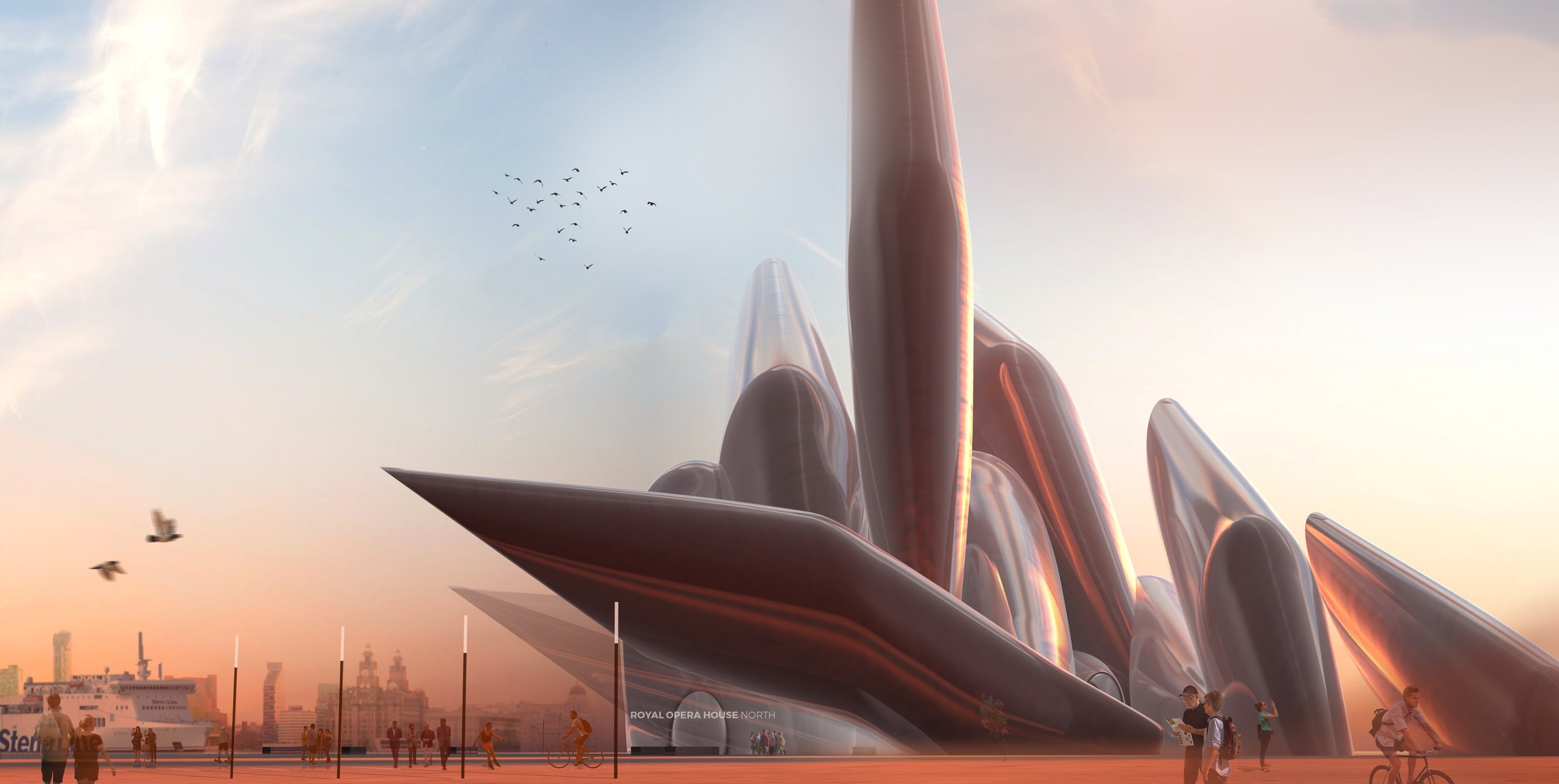

Royal Opera House North & Wirral Cultural Centre

At Liverpolitan, we’ve always believed the Wirral Waterfront to be Liverpool’s great missed opportunity. Overlooking one of the finest riverside vistas in the world, the left bank of the Mersey should be prime real estate, and yet it’s almost apologetically unimpressive – as if frightened to upstage its more famous brother. Surely, we can do better? “People laughed at the idea of Salford Quays hosting the BBC and the Imperial War Museum North,” says Michael, “but with its spectacular setting, the Wirral Waterfront should be aiming higher again.”

Two waterfronts, one city has to be the future but to really make that idea count, at some point we’ll need a significant intervention in the landscape. Wirral Council are doing good work in master planning a new Birkenhead with a better relationship to the river and Liverpolitan is all for it. But to seal the deal, argues Michael, “the Wirral needs something that stands out, something that can be seen from the Liverpool side – something that says ‘Look at me, come over to the Left Bank.’”

Given the 0.7 mile width of the Mersey between Liverpool and Birkenhead, any new landmark structure would need to be huge, gargantuan even. Taller than the 210 feet Ventilation Tower. Possibly taller than the 328 feet Radio City Tower. Cathedral-like in scale and presence. It was along those lines that McDonough put forward this earlier concept for a Royal Opera House North – aligned so that “you can see it as you look down Water Street – the two sides of the river visually connected with an iconic landmark; a catalyst for seeing Birkenhead through new eyes.”

The design is dominated by a series of steel funnels with a glinting chrome façade pointing in all directions of the compass including skyward. They would be wrapped around a central auditorium which could also have uses as a cultural centre exploring the Wirral’s fascinating history from the Vikings to its use as a monastic retreat, not to mention shipbuilding and its colourful background as a smugglers paradise.

‘The Wirral needs something that stands out, something that can be seen from the Liverpool side – that says ‘Look at me, come over to the Left Bank.’

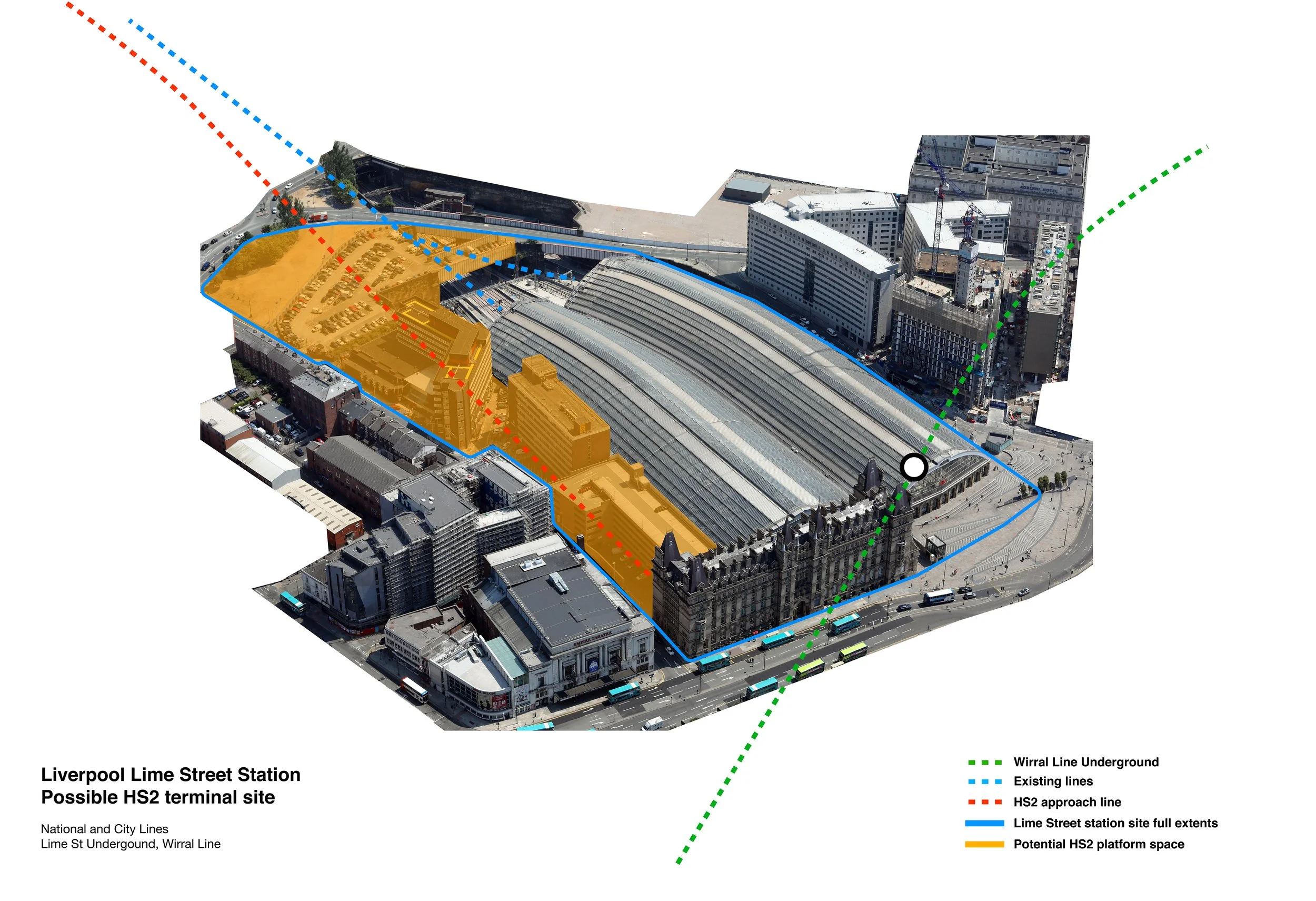

Liverpool HS2

It’s all gone a bit quiet on the High Speed 2 railway project hasn’t it? Maybe that’s a good thing – just get on and build it. But for Liverpolitan, HS2 has always been something of a poker-tell, not so much about the lack of commitment of the national government to invest anywhere outside of the south – which to be honest, we can all take for granted. No, what HS2 really reveals in full technicolour is the shallowness of Northern solidarity – some places, most notably Manchester and Leeds are consistently favoured over others like Liverpool and Newcastle. Despite the sweet words of ‘King of the North’, Andy Burnham, arguments about agglomeration are forever used to draw money and opportunity towards these investment blackholes and away from everywhere else. And HS2 has been the smoking gun. More’s the pity that Liverpool’s own leaders have been too foolish to notice (or they never cared).

When the Conservative government announced the Integrated Rail Plan for the North and Midlands in late 2021, the media was full of a wailing and gnashing of teeth. Cutting HS2’s eastern leg to Leeds and scaling back plans for Northern Powerhouse Rail was seen as more evidence of the perfidiousness of London and Whitehall. Right on cue, Liverpool’s often hapless Metro Major Steve Rotheram, joined in the venting, complaining that “we were promised Grand Designs, but we’ve had to settle for 60 Minute Make Over.”

Not for the first time, a fair reflection of Liverpool’s own particular interests was absent, but with the help of railway campaigners like Martin Sloman and Andrew Morris of 20 Miles More, Liverpolitan spotted it. The truth was, the plan might have been less good for Leeds and Manchester but it was better for Liverpool. Fresh high speed track was going to be laid closer to the city in a dedicated spur that would relieve capacity constraints and increase the scope for an expansion in freight services. In addition, the need to widen the narrow throat entrance to Lime Street was also finally acknowledged. Hurrah!

‘What HS2 really reveals in full technicolour is the shallowness of Northern solidarity – some places, most notably Manchester and Leeds are consistently favoured over others like Liverpool and Newcastle.’

Still, wanting the best for Liverpool means building new track all the way into the city centre serviced by a full specification HS2 station. By the way, what happened to the commission set up by Steve Rotheram in March 2019 and announced with full fanfare at the MIPIM Property Exhibition, which chaired by Everton CEO Denise Barrett-Baxendale, was going to choose between 2 possible locations for a new “architecturally stunning” HS2 station in the city centre as well as 5 routes in for the track? Quietly dropped?

Focusing on the most likely outcome of a redeveloped Liverpool Lime Street, Michael has put together some outline designs, which incorporated the grade-II listed Radisson Red Hotel (previously the North Western Hotel) as the main entrance to the station.

To read Liverpolitan’s cutting dissection of HS2 and the Integrated Rail Plan for the North and Midlands, check out ‘HS2 – A Liverpool Coup?’ by Michael McDonough and Paul Bryan

Or to read Martin Sloman’s examination into the options for a city centre station, try ‘Lime Street or Bust? The Options For Liverpool’s HS2 Station’

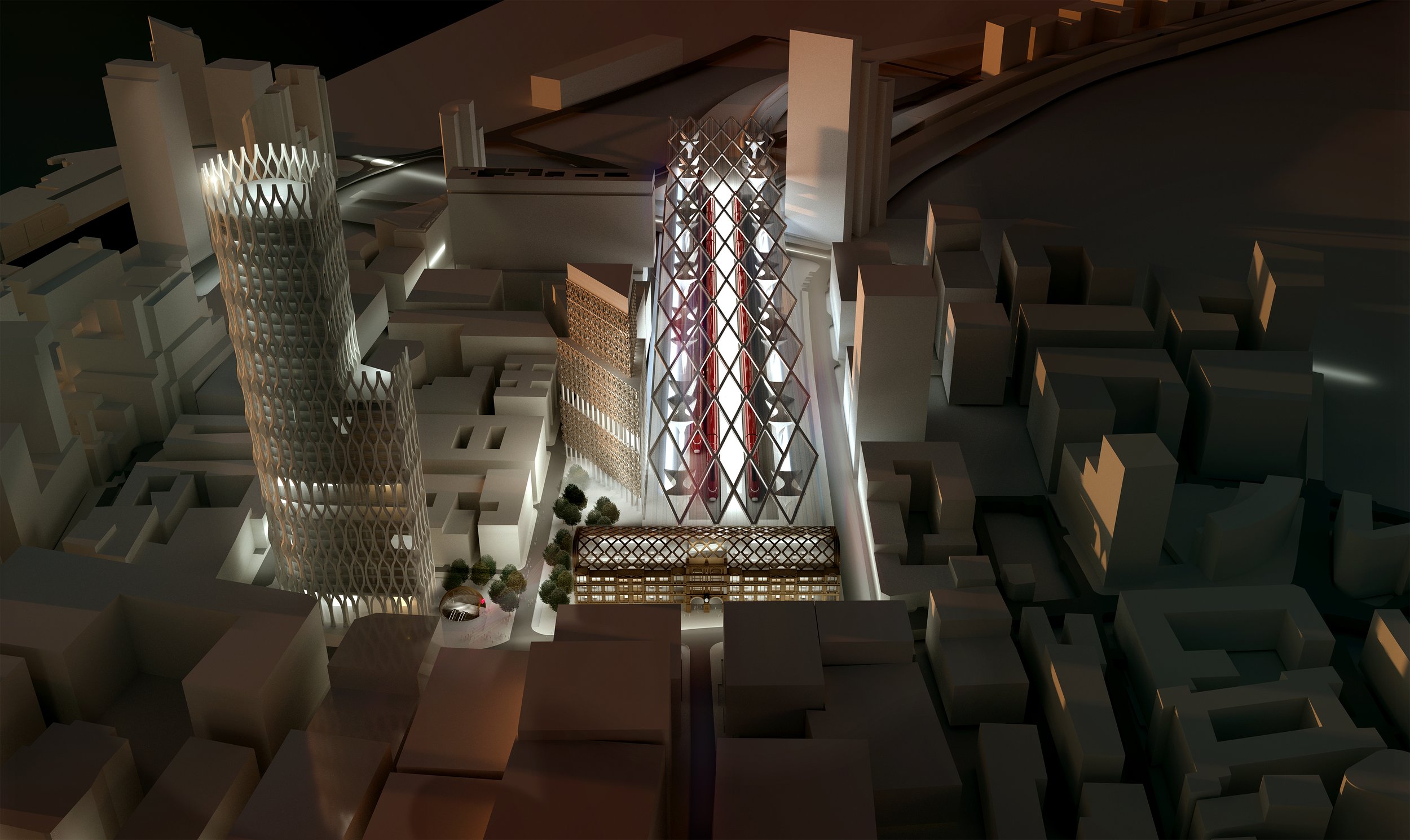

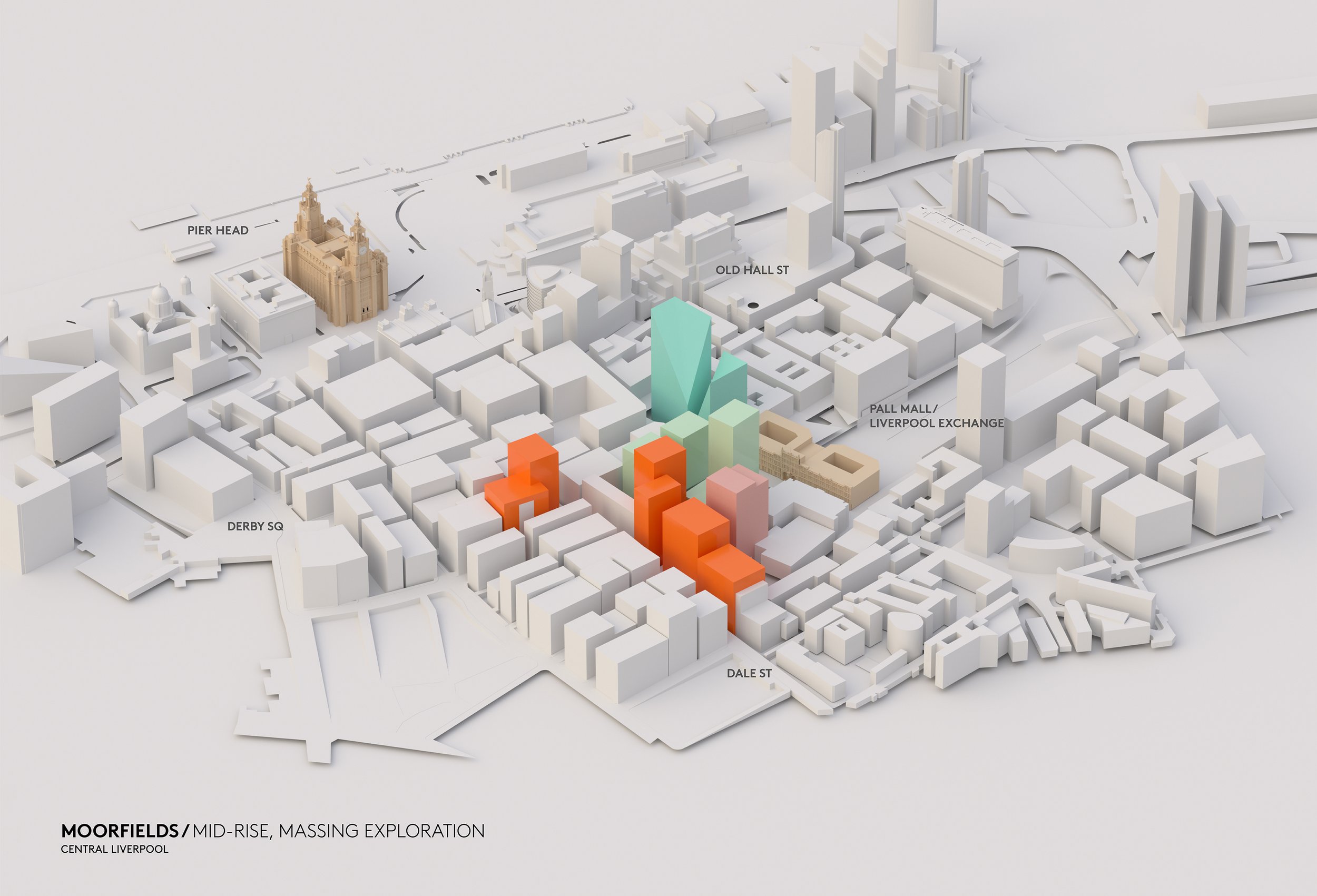

Moorfields and the Commercial District

Back in March 2023, Liverpolitan tweeted about the state of Moorfields, which we described as “a regrettable symbol of Liverpool's down at heel CBD.” We noted that the area is littered with dereliction, empty office buildings and signs of homelessness, and asked the question, “Have we become so used to this embarrassing patch that we no longer see it as failure?”

The tweet received almost 45,000 views and provoked a whole host of online conversation with the issue later picked up by the Liverpool Echo. Councillor Nick Small, who after the recent local elections is now the city’s Cabinet Member For Growth and the Economy, got involved, agreeing that the site needs to be developed. There was some discussion about whether robust plans for the area were in place already as part of the City Centre Local Plan and Strategic Investment Frameworks (SIFs). But mostly, to the extent that the local BID or the Council have acknowledged the issue, action on the ground seems in short supply.

To some extent, the lack of regeneration may be an issue of plot owners sitting on parcels of land and waiting for a payday, but as a subsequent squabble between Merseyrail and the Council over who was responsible for cleaning the grotty Moorfields escalator showed, a lack of concerted coordination between agencies leaves ample scope for things to fall between the cracks.

Moorfields is littered with dereliction, empty office buildings and signs of homelessness. Have we become so used to this embarrassing patch that we no longer see it as failure?

Michael McDonough argues that Moorfields is another of Liverpool’s great missed opportunities and it’s hard to disagree. The area’s city centre location, great transport links, and historic setting within the traditional heart of Liverpool commerce, should with the right support, allow it to live again. “The whole area needs re-invention and the drift towards noisy bars and tourism serves to cheapen its prospects,” says Michael. He claims that demolishing the rotten Yates Wine Lodge should just be the start. “Moorfields can handle density and scale and is the perfect place to rebuild Liverpool’s grade-A office offer” centred around the idea of prestige and talent.

In these visuals, Michael wanted to rebuild the entrance to Moorfields Station with mid-rise commercial office space above – no more going up to go down. He also took a stab at upgrading the former Exchange Station offices, which “may have been grand from the front, but from the rear leave a lot to be desired” – failing to properly address the park that will hopefully one day be re-instated as part of new public realm within the wider Pall Mall development.

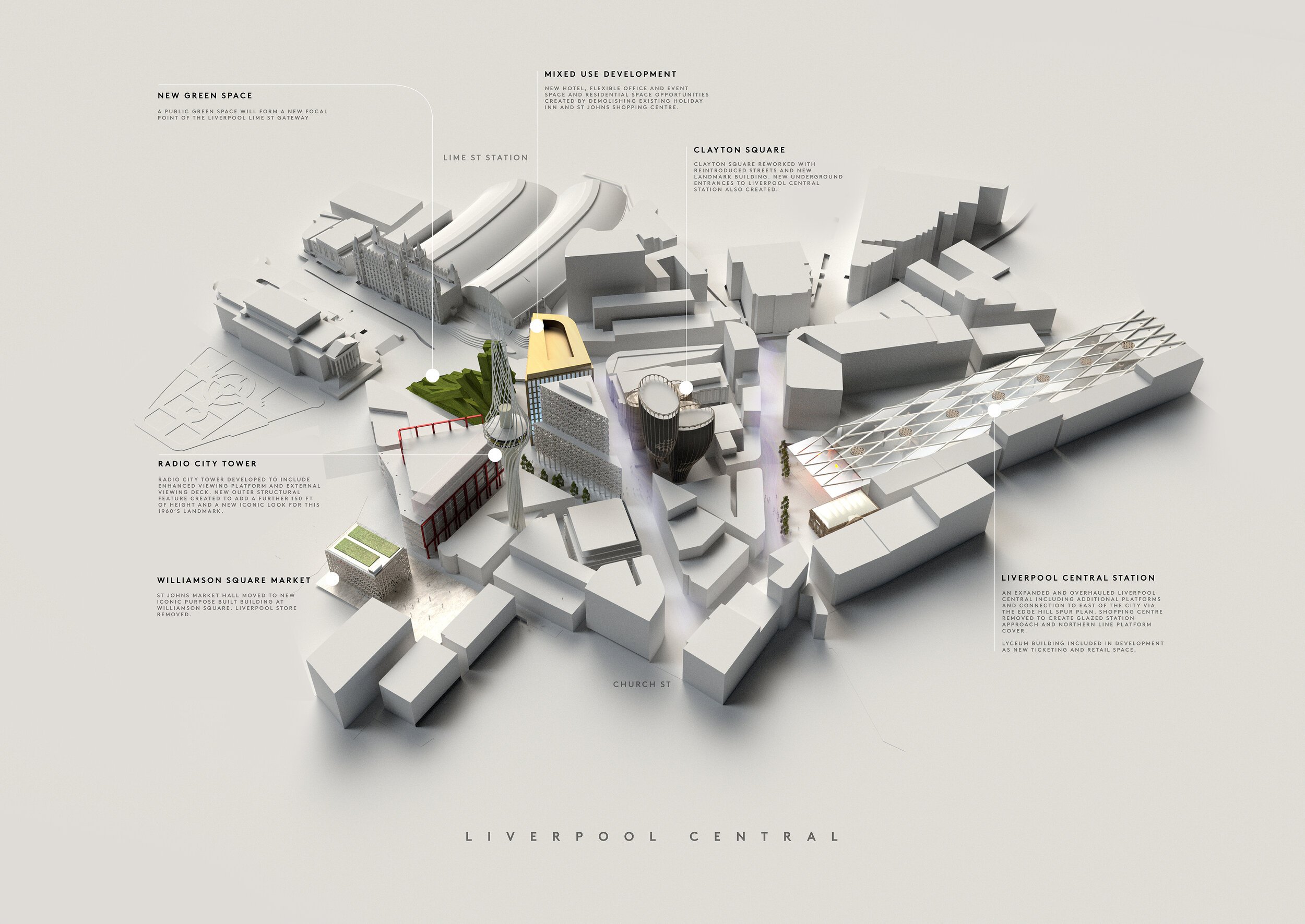

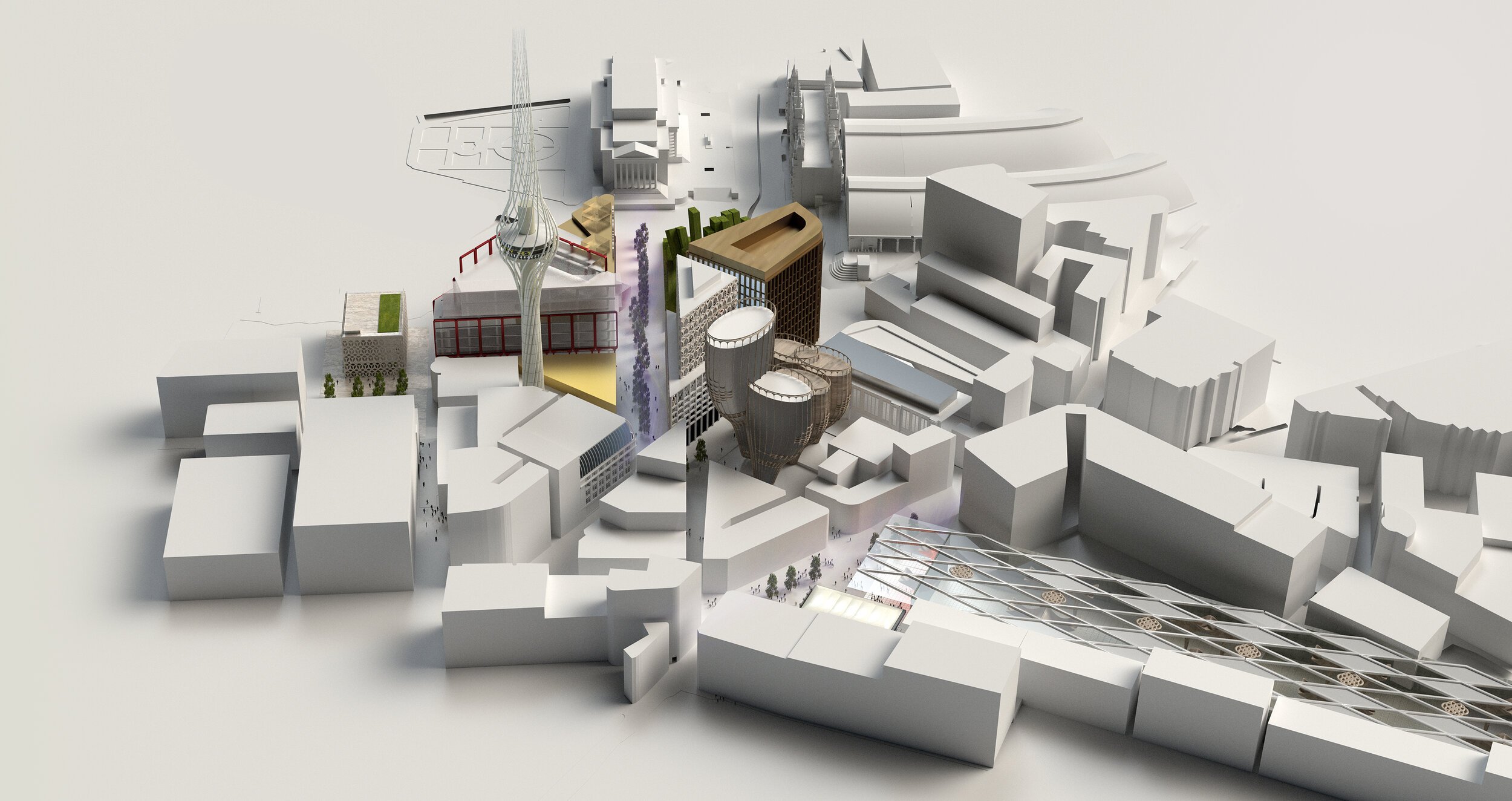

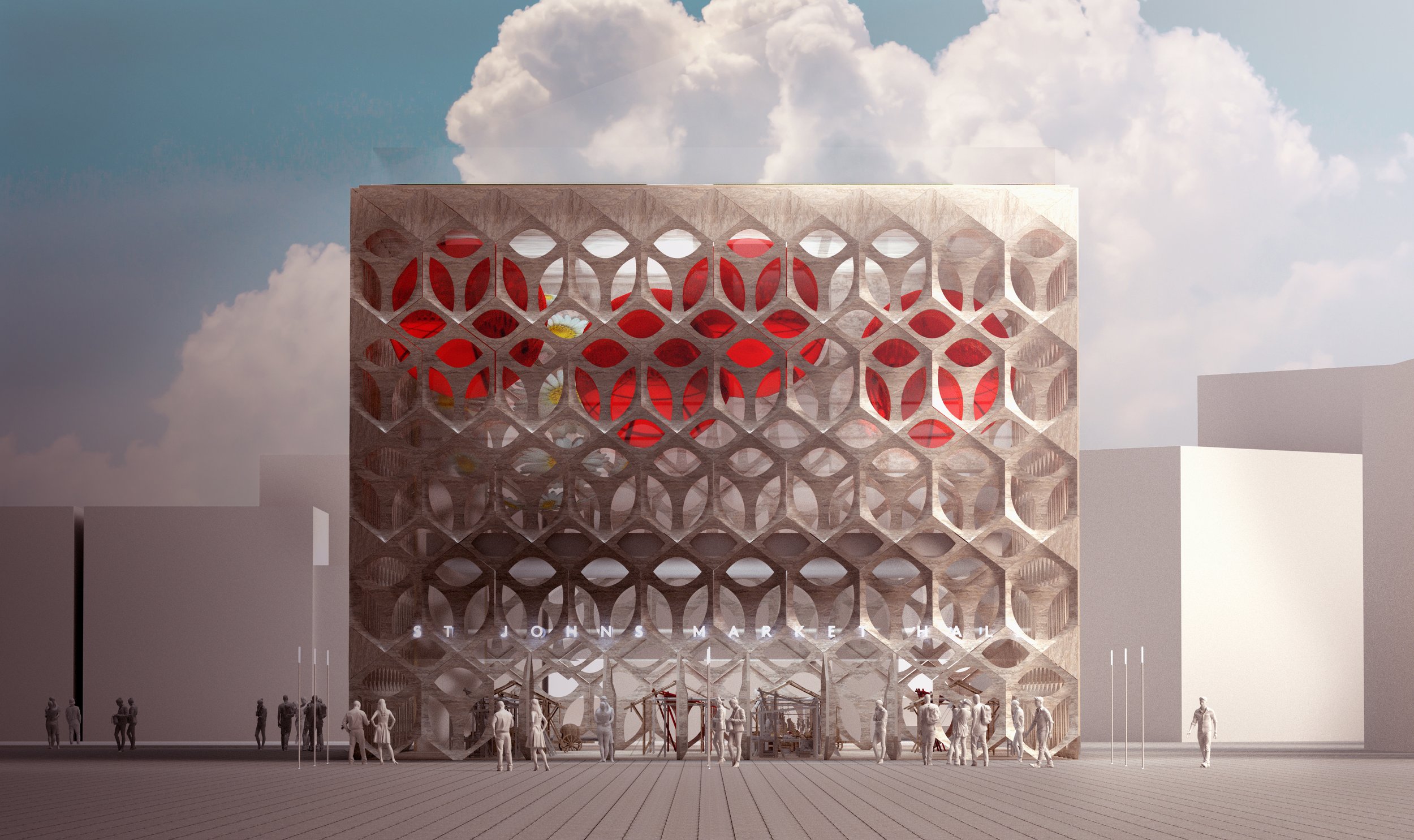

St Johns and Central Liverpool

Far, far and away McDonough’s biggest bugbear with Liverpool’s built environment has to the St Johns Shopping Centre. We know it’s commercially successful and last time we looked it had a 97% retail occupancy rate. It clearly fills an important niche within the city’s shopping offer with its cheaper rents for retailers. But damn if isn’t an ugly pig of a building (no offence to our porcine brethren). Arriving at Liverpool Lime Street, that’s the first thing you see. Talk about first impressions. Squatting over a network of old streets and the site of what would be today, if it hadn’t been bulldozed, a much valued Victorian market, Michael believes St Johns is a “dated lump of a building that acts as a physical and psychological barrier between London Road and the rest of the city centre.” It’s not a stretch to suggest that St Johns has played a role in the former’s decline. Repeated, half-hearted attempts to patch the shopping centre up have failed and its blue plastic blanket and struggling traders’ market are a testament to “a succession of bad planning decisions going back fifty plus years.” A lasting solution to all of these problems, says Michael, “requires demolition.”

The images Michael has put together here are a collection of different attempts to reinvent this “ugly and misfiring section of Liverpool.” The main driving force behind his designs is a desire to remove this “lumpen barrier” and re-stitch together our centre “in a more permeable way that evokes expressions of pride rather than cringes.” Michael wants to see a much better front door to Liverpool Lime Street – our city’s once grand hello and goodbye point. He’d like to replace this “parody of the city’s greatness” with something more iconic and ambitious.

‘St Johns is a dated lump of a building, its blue plastic blanket and struggling traders’ market a testament to a succession of bad planning decisions going back fifty plus years.’

The eagle-eyed might spot the use of neon and a prominent clock tower as a modernised callback to what the site has lost. As Michael says, “we can’t always recreate the past but we can be inspired by its best bits.” He’s also given the Grade 2-listed but still a bit ugly, Radio City Tower, a makeover, adding an elegant polished steel lattice of radiating lines which add height, fluidity and tricks of light to recast a regional landmark into one of world significance.

Read more about Michael McDonough’s vision for St Johns in the Liverpolitan feature, A New Central Liverpool.

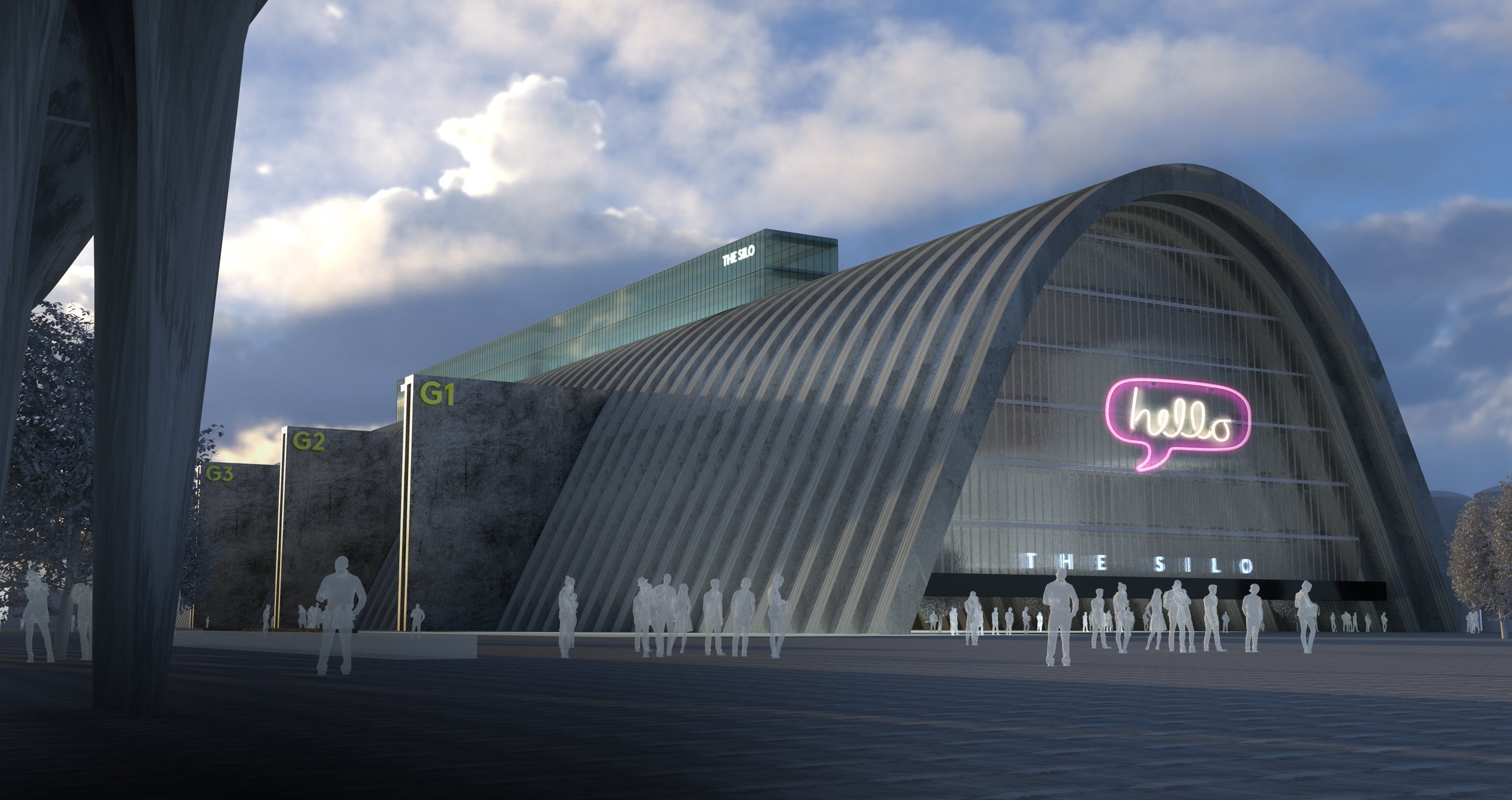

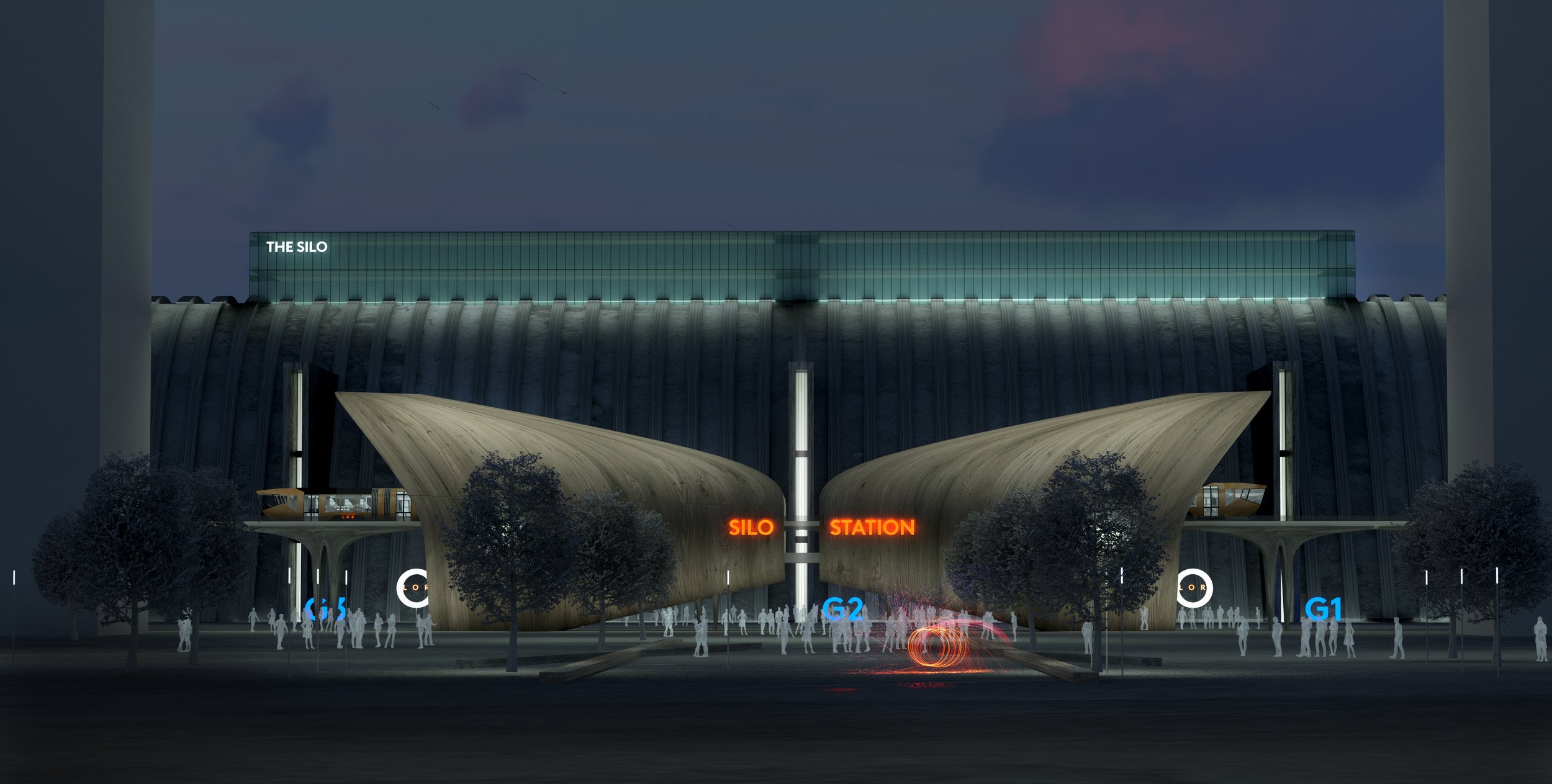

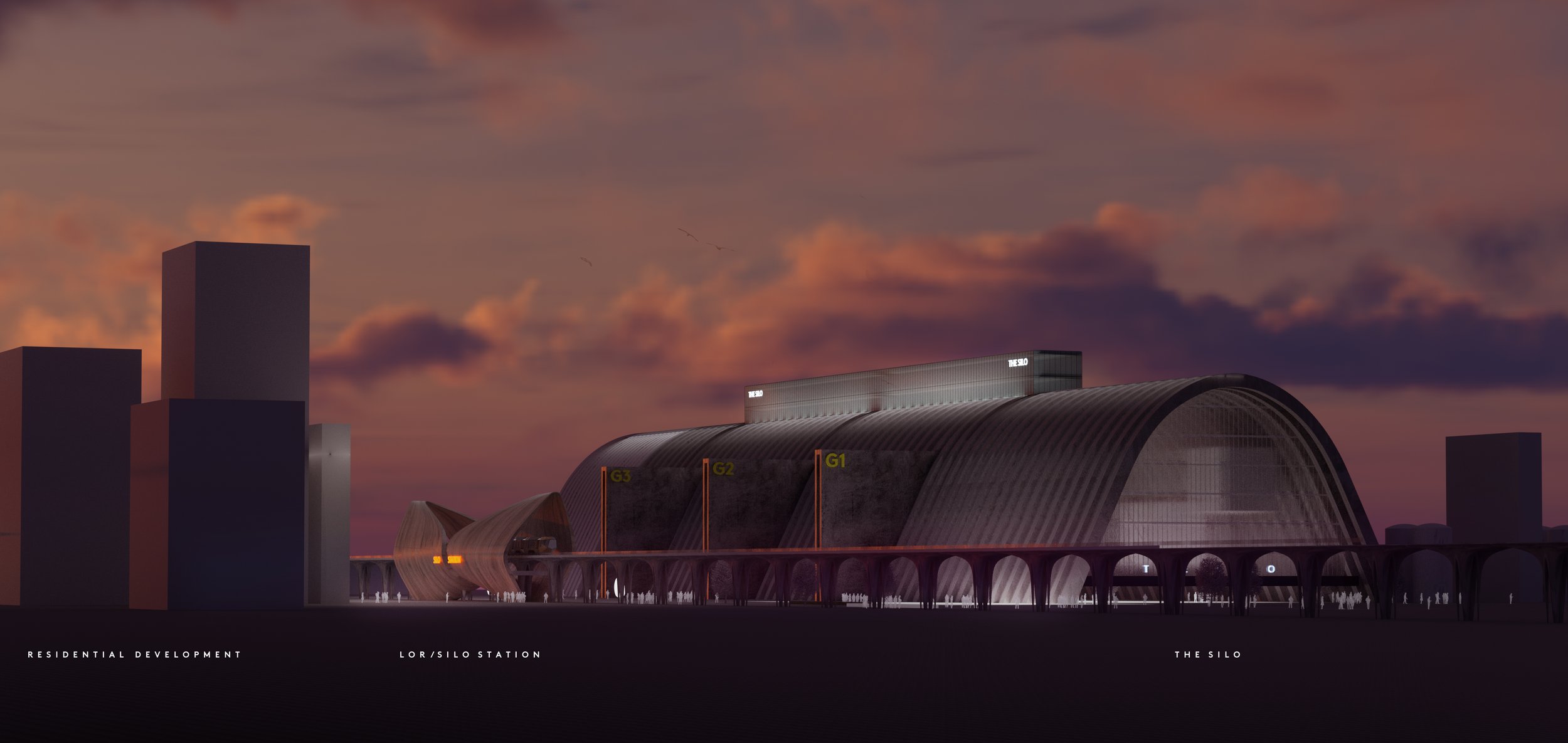

The Silo

The former grain silo in the north docks is one of Liverpolitan’s favourite buildings in Liverpool. If it was just a little further south, closer to the Tobacco warehouse and Bramley Moore, we could imagine it being repurposed as a truly iconic, high capacity arts, events and business hub. However, the silo is located deep within the working part of the dock estate with industrial infrastructure all around it, so that idea is likely to remain a dream. Still, just imagine what could be done with this incredible structure. For McDonough, the project would “represent a development challenge similar to how London’s Bankside Power Station was transformed into the Tate Modern.”

For these visuals, Michael has re-imagined the space as a media industry hub – with film, TV and radio studios and education space for our universities – “a back-up plan in case the Littlewoods Film Project doesn’t deliver.” There would also be a theatre venue, gallery space and office facilities for the production sector – which he describes as “the perfect tonic to act as a catalyst for the regeneration of North Liverpool.” Another possible use, he suggests, might be a central hub for burgeoning logistics businesses if the new Freeport ever takes off. As you can see, Michael has taken the liberty of re-instating the Liverpool Overhead Railway, with ‘Silo Station’ ready to whisk visitors straight to the doorstep.

‘What Michael is attempting to do with these designs is to remind the city that it’s capable of bigger ideas, capable of re-imagining itself, capable of statement architecture, and capable of challenging its city rivals.’

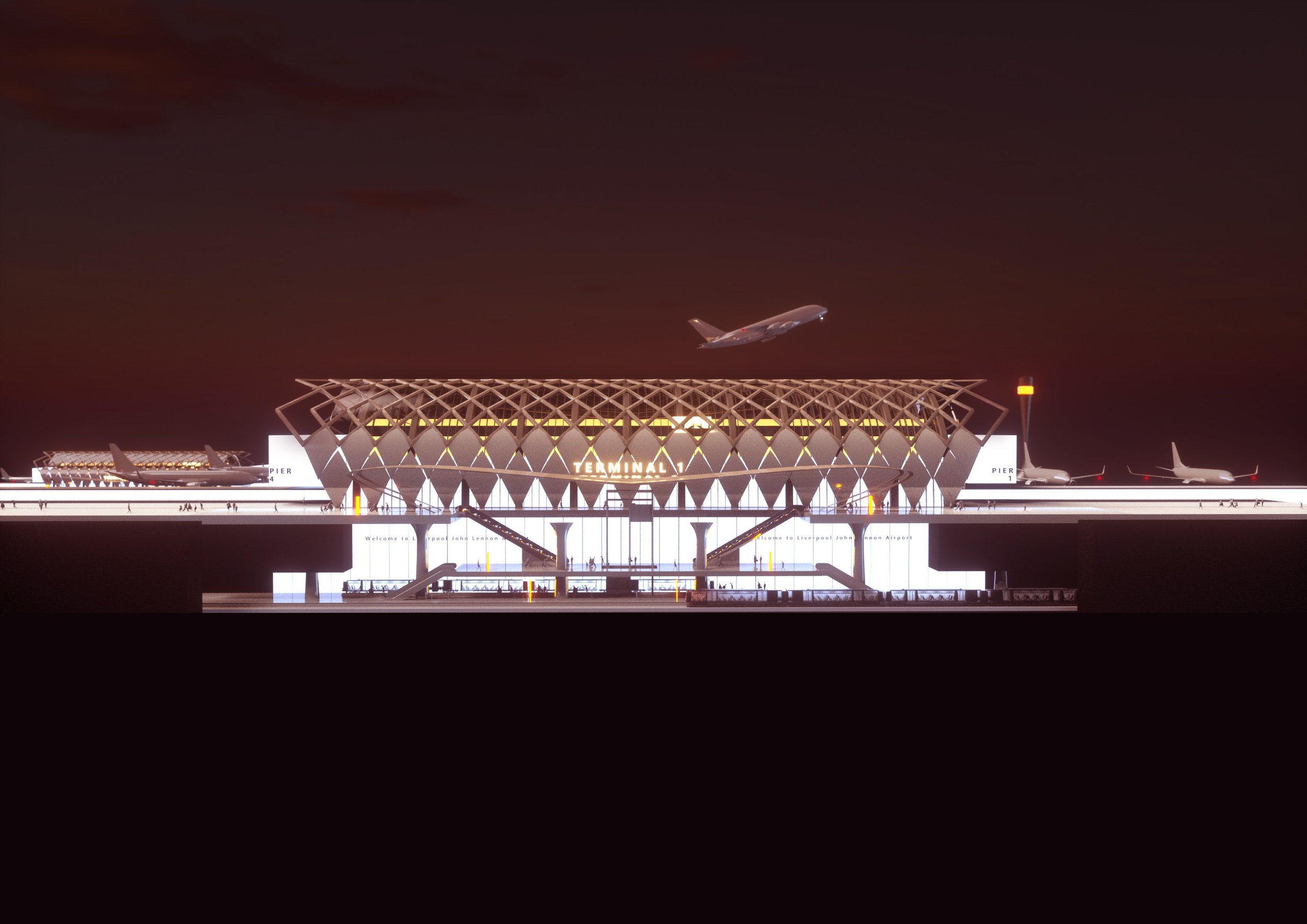

Liverpool John Lennon Airport

Not for the first time, Liverpool John Lennon Airport finds itself in a strange position. Back in the years following World War 2, JLA (minus the Beatles moniker) lost its opportunity to become the north’s most important airport when the Ministry of Defence, which had requisitioned it for the RAF, sat on the asset while its Manchester rival grew. It’s been an uphill struggle ever since.

Not that Speke Airport, as some still call it, hasn’t had its days in the sun. For a time in the early 2000s, Liverpool was THE favoured location for budget airlines in the northwest as passenger numbers ballooned from 0.6 million in 1997 to 5.5 million in 2007. That growth stalled as its much larger rival came to its senses and stopped turning its nose up at budget travellers. Still, JLA has remained a valuable strategic asset for the city, and despite the devastating blow that Covid dealt to its passenger numbers and its finances, the airport is making a solid recovery. Finally free of the dominant stranglehold of Ryanair and Easyjet, the airport is now diversifying its offer, attracting new airlines such as Lufthansa, Air Lingus and Wizz Air. And JLA continues to pick up a steady stream of awards for the efficiency of its operations, where queues tend to be largely absent.

Sad then, that Liverpool Airport has found itself consistently under attack in recent years from local environmental activists such as Liverpool Friends of the Earth and the Save Oglet Shore campaign group, who appear to want to make an example of it, by opposing all possible expansion. In fact, it’s been pretty clear in Liverpolitan’s own Twitter debates with these groups that there are those who would like to see the airport closed altogether – its miniscule contribution to the nation’s CO2 output too much for some. Others claim the farmers’ fields to the south are too ecologically important to lose or that air quality is impacting the health of local residents – the result in part of some very strange and short-sighted choices by the Planning Department on where to locate new residential developments. Inexplicably, our council continues to have a very ambivalent attitude to what should rightly be viewed as a key enabler of our economic prosperity.

‘The reality is, the healthy human desire to travel and see the world will not and should not be legislated away by those with a dystopian vision of the future.’

The reality is, the healthy human desire to travel and see the world will not and should not be legislated away by those with a dystopian vision of the future. The technical challenges to realising a cleaner way to fly are immense, but they are not uniquely Liverpool’s burden and no other city would so blindly hobble itself in restriction.

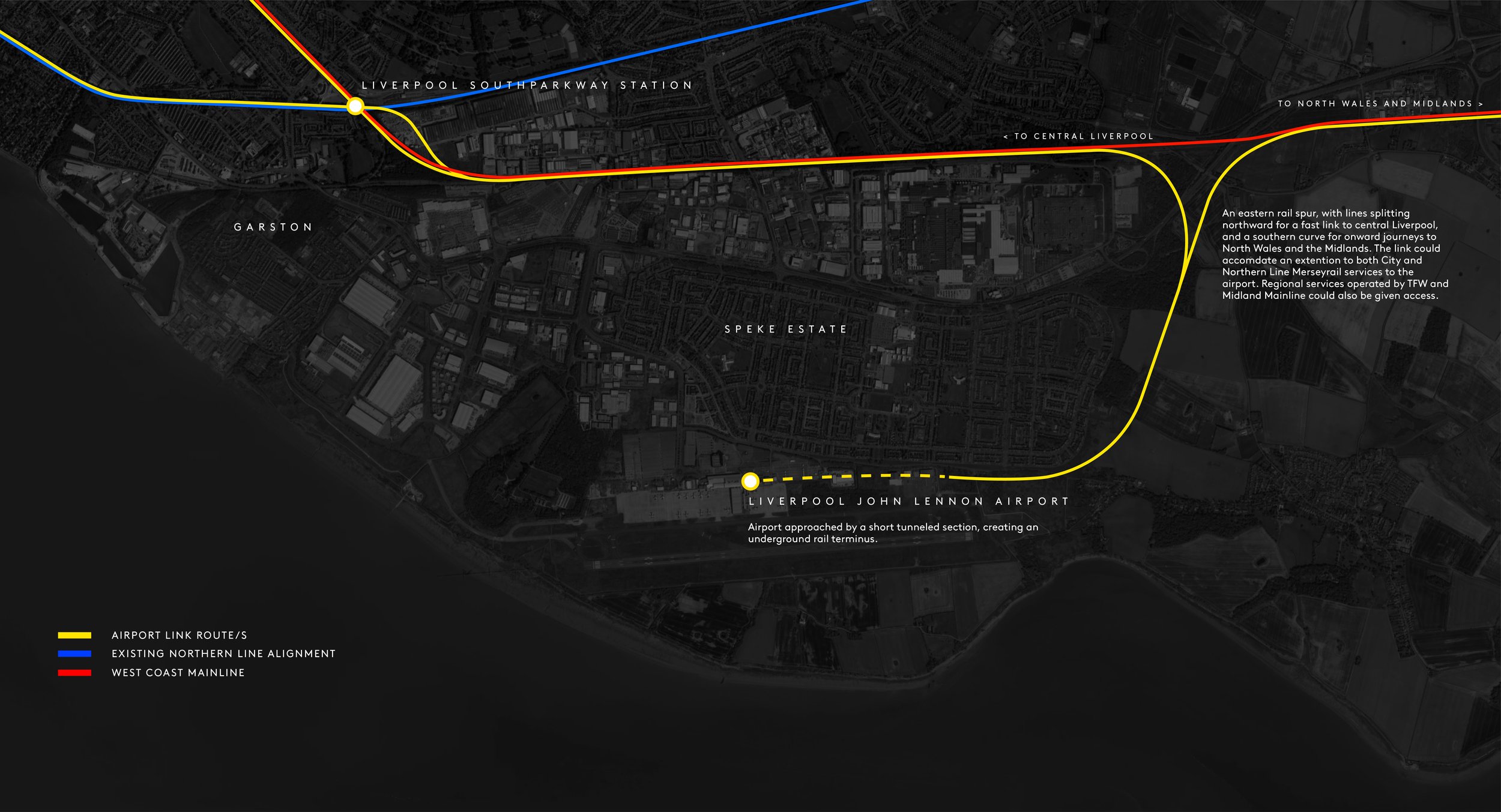

Michael McDonough grew up next to Liverpool John Lennon Airport and has seen its infrastructure grow from “a small, bland, industrial shed of a terminal into something more befitting,” and at some point in the future he believes it will need to expand. Michael argues that better public transport provision should be a priority with an extension of the Northern line or a tram connection mooted as alternatives. In these designs, Michael has proposed a train line that tracks underground for the final few hundred meters to arrive directly at a much expanded terminal. The capacity of the current structure is around 7 million, so if JLA can hold onto its post-Covid gains and continue to build upon them, discussions about what comes next will be inevitable. “The myopic few who claim the northwest already has a large airport and doesn’t need another, are shutting their eyes on the obvious.,” says Michael. “Demand for flying will continue to rise and the north can easily sustain a larger Liverpool John Lennon Airport at Speke.”

Northern Assembly

Given the shenanigans at Liverpool City Council in recent years, it might seem strange to suggest our city as the seat of political governance for the whole of the north. But a Labour government is a distinct possibility come 2025 and they’ve often flirted with the idea of greater regional devolution and a northern assembly to govern our unruly mob. Manchester is the usual default option, of course, but at Liverpolitan we can’t be having that. Perhaps only Newcastle can offer the grandeur of our riverside estuary setting here on the Mersey. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Liverpool took inspiration from its darkest days to become a paragon of democratic values? To take accountability and citizen engagement as its governing principle, to put behind it the days of boss politics and party before city, and instead show the world how local government is done when at its best.

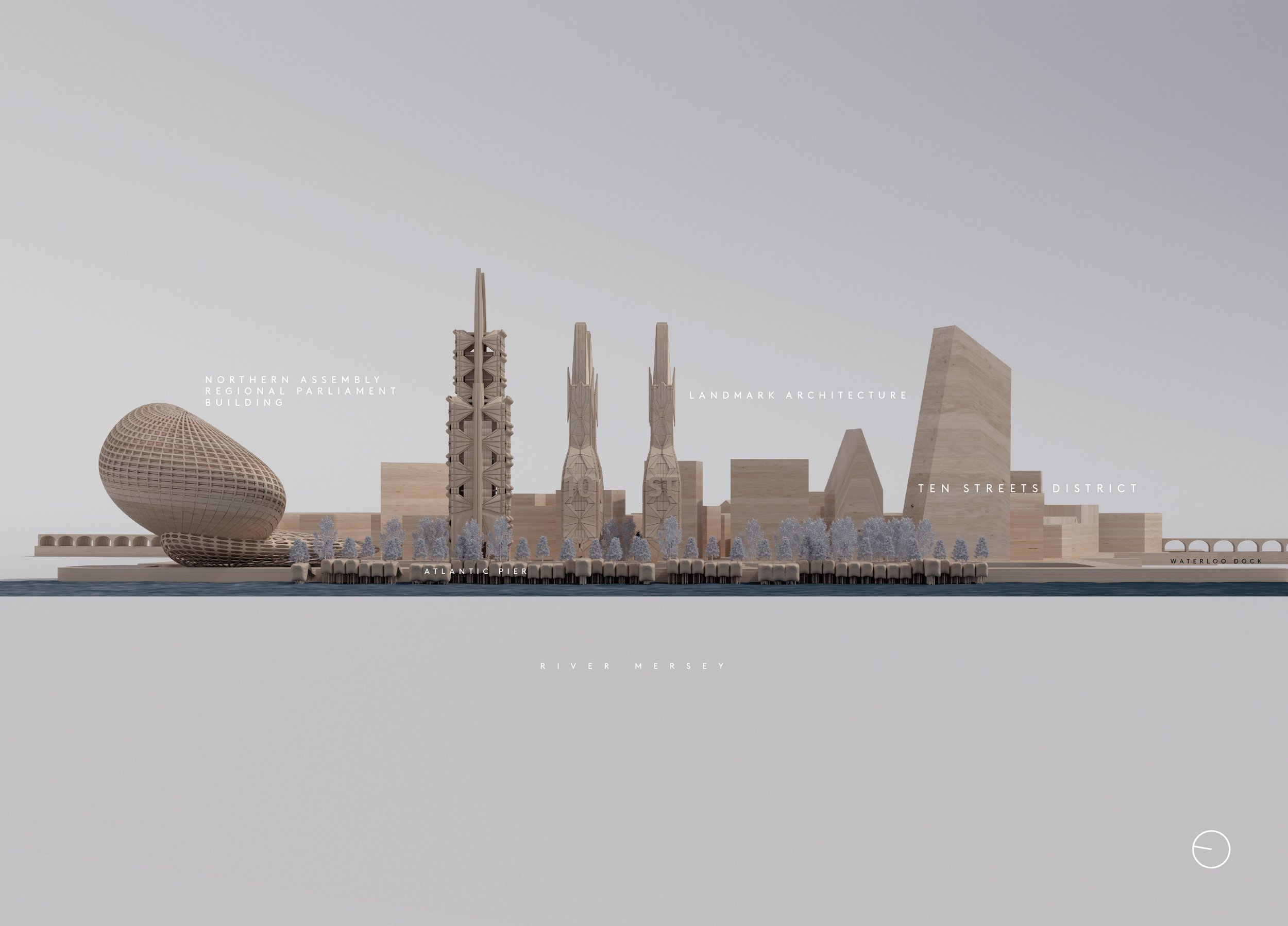

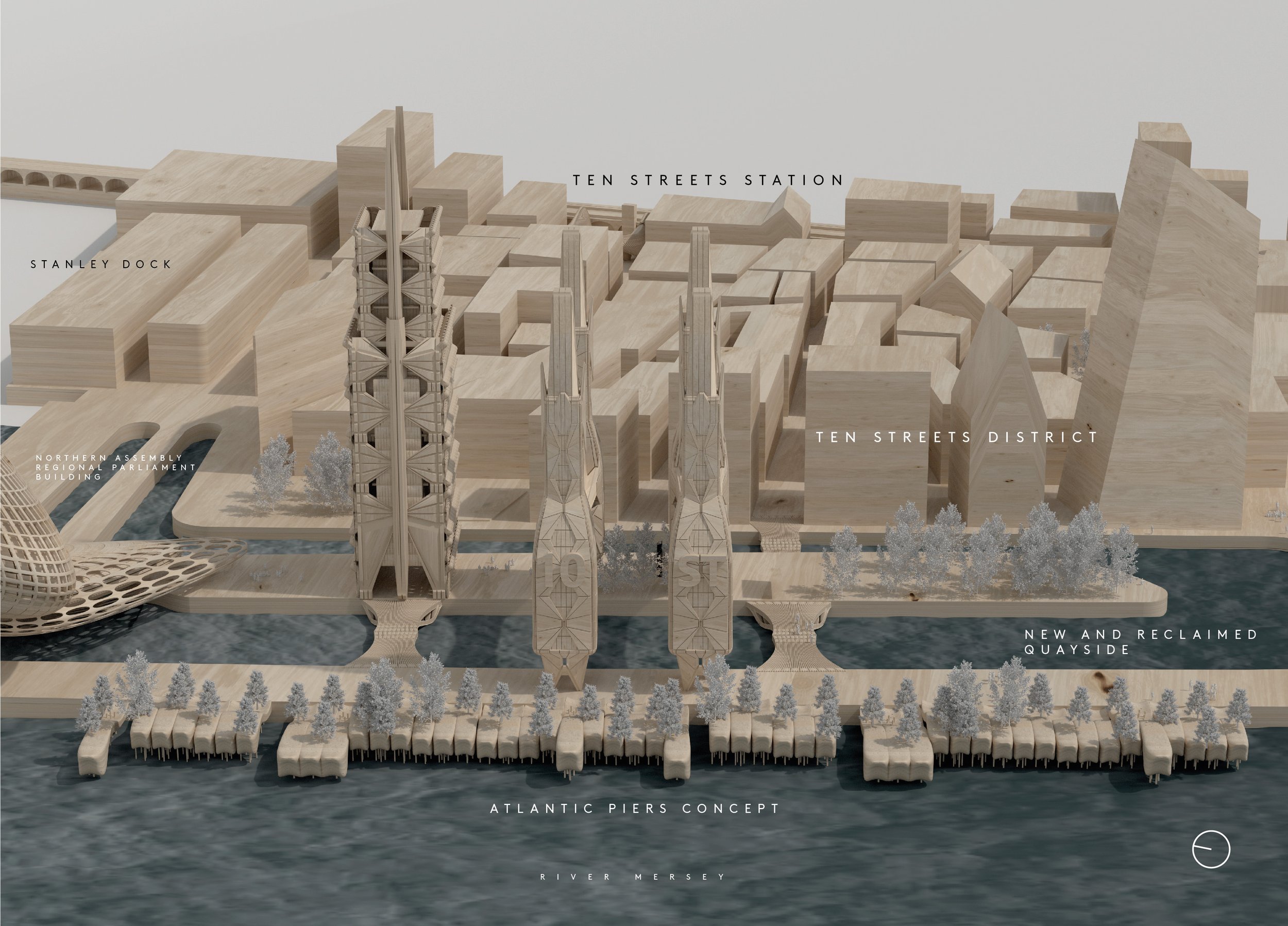

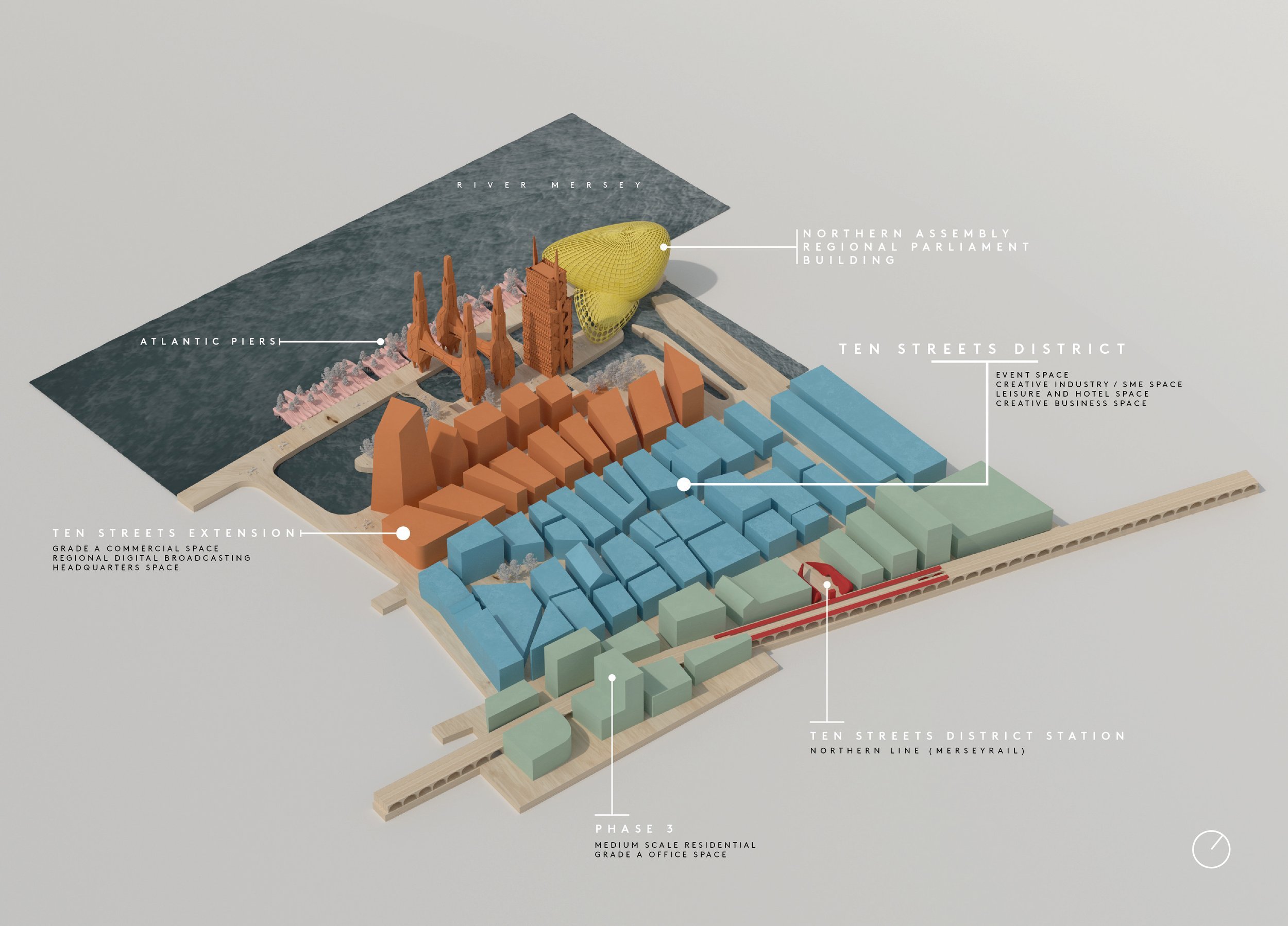

McDonough’s design of a new Assembly district is based on a wholly different concept to Peel’s current underwhelming plans for Liverpool’s central docks – albeit quite capable of incorporating a sizeable, new park. The site encompasses a parliament building, ancillary office space, a new cultural centre with notes of modern gothic and an extension of a revitalised mixed-use Ten Streets area including substantial residential to repopulate the area and give it life. In these days when the potential for terrorist attacks is sadly a design factor, Michael believes the location’s riverside setting has unique advantages, making it defensible for security services. Addressing concerns about the loss of ‘blue space’ at Waterloo Dock, he has increased the provision of waterways by reclaiming some of the infilled land, and bridging buildings across it. This Michael explains is “meant as both a symbolic and practical gesture of compromise in a city often at loggerheads with itself on how to reach for the stars architecturally without compromising existing heritage elements.”

Naturally, this substantial expansion of our city centre, requires transport infrastructure, which Michael has designed in with a new station at Vauxhall on the Northern line. Such investments in transport become more viable as we add additional all-year-round uses instead of just relying on the footfall that the new Bramley Moore stadium will provide.

‘Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Liverpool took inspiration from its darkest days to become a paragon of democratic values? To put behind it the days of boss politics and party before city, and instead show the world how local government is done at its best.’

For a fuller exploration of this concept, read Michael McDonough’s Liverpolitan feature, Welcome to the Assembly District.

Liverpool Central Station

The redevelopment of Liverpool Central Station has long been on Merseytravel’s wish list and it’s not hard to understand why. Boasting the highest passenger numbers of any underground station in the UK outside of London, Liverpool Central is, despite recent minor refurbishment, “a dark, dated and cramped station prone to over-crowding,” according to Michael. Its current single island platform structure and track layout on the Northern Line section also places restrictions on train capacity. A full scale expansion of the station, which the Liverpool Combined Authority are pushing central government for, would allow more trains to run through services linking up the Northern and City lines via a re-used Wapping Tunnel. This would in turn free up capacity at Lime Street Station enabling it to focus on its role as an intercity and regional transport hub.

A few years ago there were grand plans to convert the old Lewis’ department store which sits next to Central Station into a new shopping centre accommodating new residential blocks. A side benefit of the scheme was the use of Lewis’ ground floor to open up a new, additional entrance to the station itself. However, the proposed scheme, which ultimately came to nothing, left intact the tired, almost prefab current station entrance – “a pale shadow of what was once a magnificent Victorian railway terminal,” says Michael.

McDonough believes that when the time comes to rebuild this thing, we should “go all out and design a station that lets in the light.” These visuals imagine a doubling in the size of the station envelope, with an additional platform, and the complete removal and replacement of the shopping arcade with a dedicated railway concourse at the street level front end. The plan would allow the floor above the underground platforms to be removed allowing sunlight to reach down to create a much more welcoming environment. Reinforced as a major local transport hub for the city, and with the poorly performing shopping centre now gone, Michael believes the wider site offers potential to “accommodate new office and residential accommodation at impressive scale.”

‘The proposed scheme, which ultimately came to nothing, left intact the tired, almost prefab current station entrance – a pale shadow of what was once a magnificent Victorian railway terminal.’

New Brighton Pier and Observation Tower

The advent of foreign travel certainly did for many of Britain’s seaside resorts. Still, nostalgia aside, glancing through old photographs of New Brighton does makes the heart bleed for what was lost. It’s hard to think of a more striking example of the region’s self-destructive attitude towards its built environment than the loss of the old ballroom and tower, fire or no fire. Not to mention its pier, pleasure grounds and lido. Daniel Davies of Rockpoint Leisure has been doing his bit in recent years to bring a bit of hip to Victoria Street and the Championship Adventure Golf course is well worth a visit too. In fact, there are tentative signs that Wirral Council are starting to understand what they have, even if the area has been stripped of many of its key attractions. Liverpool’s Left Bank can and should be a treasured beauty spot, a place for families to enjoy and a haven for the avante garde and edgy. Now is the time to think bigger.

Michael hasn’t yet worked on a full plan for New Brighton but bringing back some kind of landmark beacon with a viewing deck, visible from the other side of the Mersey and prominent to the passing cruise ships feels like it should be part of the picture. Back in the early 2000s, sculptor Tom Murphy proposed a 150-foot statue of the Roman god, Neptune, to sit in the waters at the mouth of our mighty river – Liverpool’s equivalent of the Statue of Liberty or the Colossus of Rhodes. Oh, how we’d like to have seen that! Or if money was no object, two of them either side of the river standing proud like the Argonaths of Lord of the Rings. In the meantime, Michael McDonough took a stab at a slightly less monumentalist beacon a few years ago.

‘Back in the early 2000s, sculptor Tom Murphy proposed a 150-foot statue of the Roman god, Neptune, to sit in the waters at the mouth of our mighty river – Liverpool’s equivalent of the Statue of Liberty or the Colossus of Rhodes.’

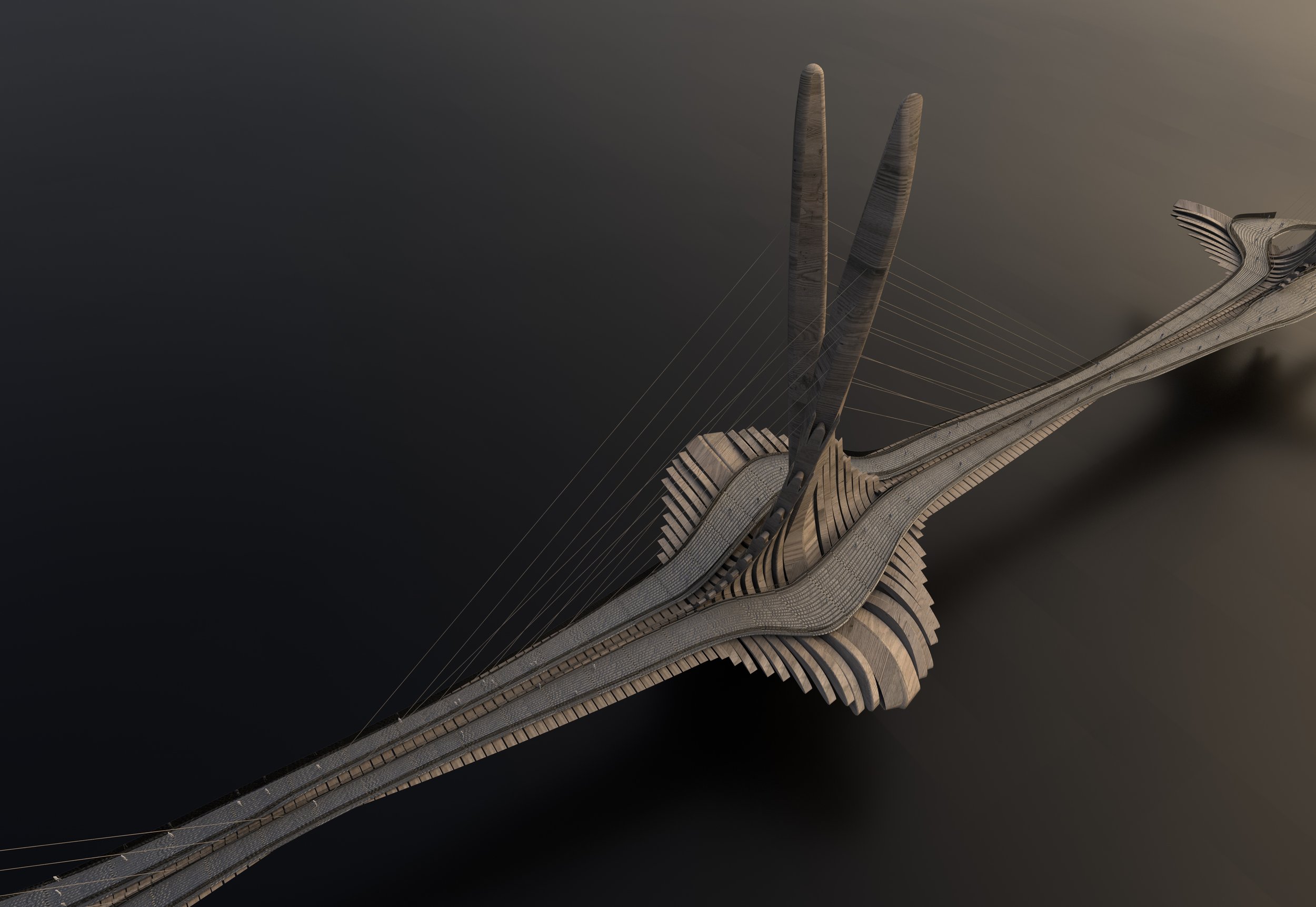

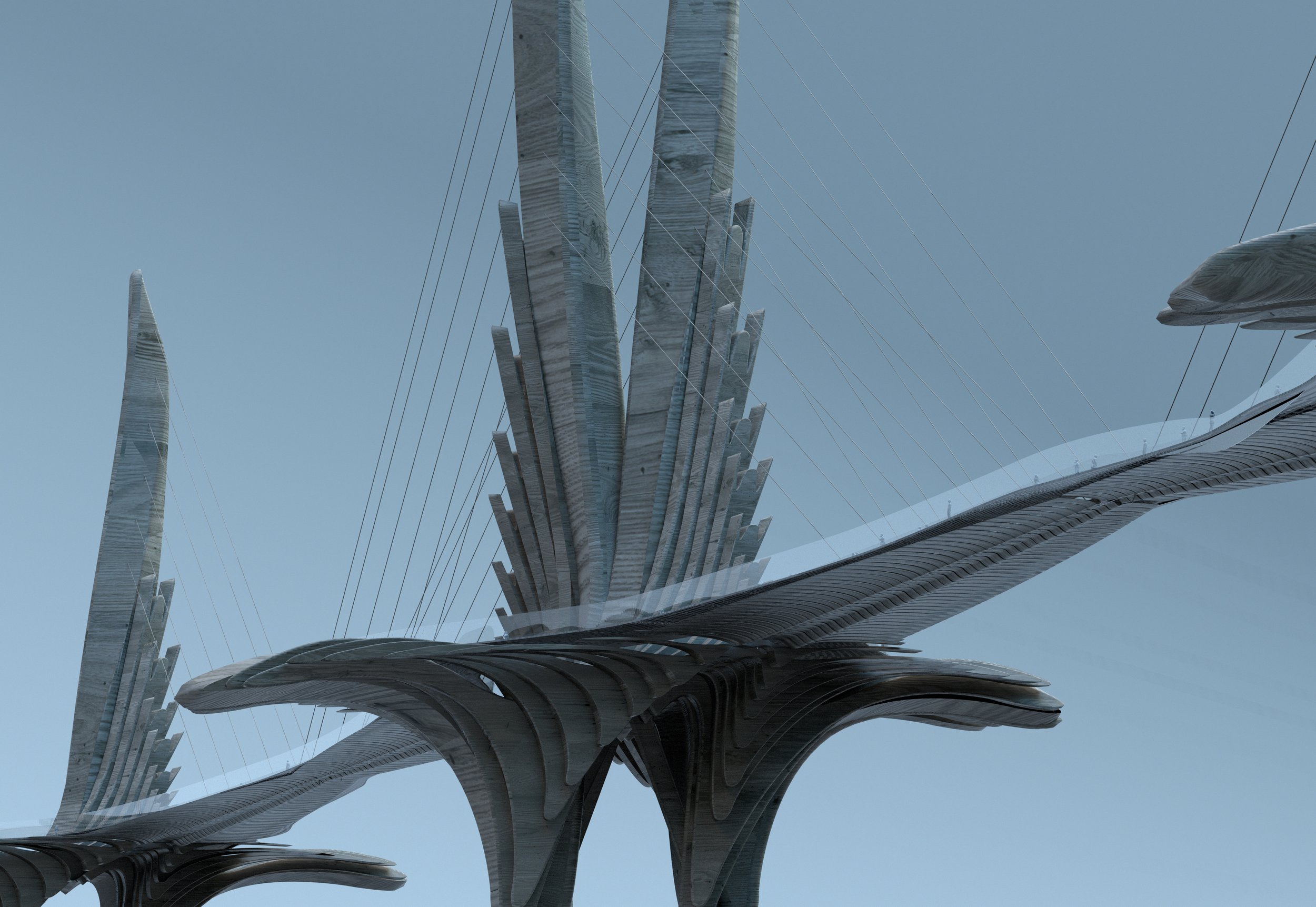

The Liverpool ‘Angel’ Bridge

Unashamedly a flight of fancy and almost certainly the most outlandish of McDonough’s ideas, the concept of a bridge linking Liverpool and Birkenhead delivers an element of San Francisco’s Golden Gate magic and then tries to one-up it. There’s something slightly Game of Thrones about this design, which Michael says he wasn’t consciously thinking about at the time. “It’s intended as statement architecture,” says McDonough, “A big ‘Here I am’ to the world that would forever add a new image to the iconography by which Liverpool is known.” The idea behind it is to unlock the two sides of the Mersey as one urban centre, transforming Birkenhead’s prospects for the better. It would, of course, be ludicrously expensive and so is likely to remain one for the mind’s eye. “Building this kind of structure would take serious doses of civic ambition and that’s the kind of vision we don’t often see in these parts,” said Michael.

For those worrying whether the bridge would undermine the Mersey tunnels, it has been designed as pedestrian-only, although it could be adapted to accommodate light rail or electric tram-buses. In terms of location, on the Liverpool side, Michael imagines it would sit between the Albert Dock and the Museum of Liverpool, while over at Birkenhead, the bridge would land at Woodside, right next to his alternate proposed site for an Opera House North.

“It’s intended as statement architecture”, says McDonough, “A big ‘Here I am’ to the world that would forever add a new image to the iconography by which Liverpool is known.”

…and finally.

Project vision and designs by Michael McDonough. Article by Paul Bryan.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Can Liverpool be Liberated from Labour?

From black ops-style campaigns to discredit rival independent candidates by the local Labour Party to the unlikely rise of the ultimately doomed anti-corruption movement, Liberate Liverpool, the city’s local elections proved to be one of the most fiercely contested in years. And then Labour won. Writing for UnHerd on the eve of the election, Liverpolitan Editor Paul Bryan describes the fervid atmosphere of the campaign amongst the hopes and shattered dreams of candidates of all colours.

Local Elections 2023

Paul Bryan

This article by Liverpolitan Editor, Paul Bryan was published by UnHerd on 3rd May 2023 on the eve of the 2023 Local Elections in Liverpool. To read the whole feature visit…

Before Liverpool can bask in the joy of hosting next week’s Eurovision Song Contest, it must first contend with tomorrow’s local elections — and the rounds of mudslinging that have come with it. Take one of Labour’s election pamphlets, pushed through the letterboxes of residents in the south of the city. Disguised under the banner of Garston Resident News, the leaflet mined old social media posts belonging to independent councillor, Sam Gorst, who had been expelled from the Labour Party in December 2021 for associating with Labour Against the Witchhunt, a group opposed to “the purge” of pro-Corbyn supporters for alleged antisemitism.

Under the headline “Sickening”, Gorst was criticised for historic posts in which he called Queen Elizabeth “a useless bitch” and the Jewish former Liverpool Wavertree MP Luciana Berger, who eventually resigned from the party, a “hideous traitor”. The pamphlet also claimed that he lived in a “leafy” area and insinuated that he had jumped the queue on social housing, although that accusation is contested.

But if the intention was to make an opponent look bad, Labour may have shot itself in the foot. A joint statement released by the Liberal Democrats, The Liverpool Community Independents, The Green Party and the Liberal Party described the leaflet as “cynical”, “dishonest” and “shameful”. Their calls for a clean fight, however, have fallen on deaf ears, not least because the mud is being thrown in all directions amid widely reported allegations of Labour corruption and incompetence.

“In cities with a more contested political complexion, one might expect such failures to be severely punished at the ballot box. But this is Liverpool, and ousting Labour is the toughest of political challenges.”

Snippet taken from a Labour election pamphlet disguised under the banner of Garston Resident News,

To read the whole article visit…

https://unherd.com/2023/05/can-liverpool-be-liberated-from-labour/

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

The tales we tell. Why Scouse stories of strength and resistance matter

Liverpool should never turn its back on a troubled past. On the contrary, as Patrick Devaney argues in this reply piece, it's not our suffering but our record of showing strength through adversity that defines us and the stories we tell about ourselves.

Patrick Devaney

In a recent op-ed entitled, Why we need to stop banging on about Thatcher and the Toxteth bloody riots, Liverpolitan Editor, Paul Bryan argued that focusing on the city’s past risks pinning Scousers as “irrelevant, backward-looking, and worst of all, passive in the face of the present” and can offer us only “a shrunken vision of our place in the world… a tiny Scouse Republic of Retreat.” I feel compelled to respond to this as I believe there is no need to look down on the hard times the city has been through or shy away from the broken images of urban decay that haunt our past. It is what it is, and we are who we are. There is no shame in who we are and highlighting the challenges we’ve faced in the past does not mark us with a “Petty Scouser” point of view.

Rather, for me, one of the key reasons we shouldn’t be turning our backs on the past is the fact that, unfortunately, the future increasingly now looks more like the past. It’s not like austerity ever really went away, but now, with austerity 2.0 biting up and down the country, we need the strength to pull together more than ever. Furthermore, there’s no reason to think that the outward-looking agency Paul craves cannot be found in the extreme challenges the city’s inhabitants have faced together. Communal adversity can spur social and political movements that change the world. However, there are limits to how far identity can take us and I intend to show in this response article that while our common heritage offers us strength in our identity, that very identity can only take us so far because of the very ideals of justice and kinship that it is built upon.

For a prime example of the power shared adversity offers we can look to New York in the 1960s and 1970s where we see similar images of urban decline to those that grip the imagination when thinking about the Toxteth Riots and 1980s Liverpool. Influential American city planner, Robert Moses, carved out city projects from roads and bridges to housing and parks that treated the existing New York landscape like a blank sheet of paper. With his eyes on the suburbs and the ubiquity of the motorcar, he cut through densely packed working-class and ethnic residential communities to construct the Cross-Bronx Expressway. His plan led to the demolition of hundreds of residential and commercial buildings and displaced the families and businesses they housed. Moses also enacted a slum clearance programme that designated many more densely populated and stable Bronx neighbourhoods inhabited by mostly working and lower-middle class Jewish, Italian, German, Irish and Black communities as being slums. Ultimately, Moses forced more than 170,000 people to abandon their homes for demolition in the interests of “progress” and “modernisation”. However, despite this marginalisation and wanton destruction, something began to stir in those ruined blocks and devastated neighbourhoods. Underneath the busy expressway that the better-off used daily to pass them by, youngsters in the Bronx began defining themselves through the formation of a new culture built on spray paint and tags, breakbeats and heavy bass, rhymes and ‘disses’ and pops and locks. In the face of Moses’ actions, Hip Hop was born and has been acting as a force for cultural and social revolution ever since.

It all sounds familiar, doesn’t it? Social dislocation, economic deprivation and racial discrimination wrought by an uncaring overseer that cares not for the people of certain communities. So, what do we do then, when our history is filled with similar social dynamics? Do we turn our backs on events because they’re “negative”, or build upon them because they’re real? As the Bronx experience clearly shows, when times are hard, they can fuse a shared sense of identity within the communities that live through them. This can be a source of strength so powerful it can push even the most marginalised in society to change the world.

‘So, what do we do when our history is filled with similar social dynamics? Do we turn our backs on events because they’re “negative”, or build upon them because they’re real?’

In fact, nation-states are built upon that very power. The shared myths and heritage we teach ourselves and the persecutions we have faced together are what bind us to people we have never and will never meet. From wars fought and lost, to great works of art, pride in scientific advances, songs and literature or notable sporting moments, our shared experiences and memories, both first-hand and passed down, all contribute to a common idea of identity that moves us beyond the limits of our own personal horizons. That’s why I think it is so self-defeating to turn our backs on the common myths we share as people from Liverpool. They offer a source of strength that can power us to change the world again.

These stories from our past are not restrictive either. We don’t need to get caught up in definitions when discussing our common heritage. Rather than defining who we are, it creates a shared foundation upon which we all can build as people of this city, whoever we may be. A gravitational pull around which we, no matter our background, are all orbiting in our own way. This includes many potential variations among us with some focusing on the implications of this story and others on their recollections of that event. Our common heritage does not lock us into our past, but rather offers us a rich tapestry upon which we all have the chance to make a mark, shaping and defining our ideas of this city and who we are as we move into the future. We are in charge here.

If we turn our gaze north of the border to Scotland, we can even see how these common myths can generate real political power. The Scots, whom people from Liverpool should be proud to call brothers and sisters, have a recognised nationality that has enabled them to fight back against the diktats of Westminster in ways we can only dream of. Scotland’s common myths form a foundational basis for a recognised national identity that offers them real political power, while ours do not.

Interestingly, however, while huge swathes of the Scottish national identity undoubtedly come from centuries of wars with the English, there is no denying the fact that it was Edinburgh and London together that spread the borders of the British Empire from one end of the world to the other just as much as it was Liverpool and Glasgow too. I would argue then that much of what feeds the Scottish National Party’s continued impressive showing at recent Scottish elections is more to do with the Poll Tax and Prime Ministers than it is to do with English kings like Edward I. If Scottish nationalism in its current form is built at least in part on the marginalisation it feels today, then it is built on the same marginalisation felt in Liverpool, as well as communities across the North of England, through the Midlands, and into Yorkshire. Therefore, despite our common imperial history and the decades of marginalisation we’ve lived through together, Scotland has a much better deal than the rest of us. Scottish common myths have delivered free universities and free prescriptions while ours, even though they are similar in nature, see us with Conservative commissioners running our city.

Clearly then we can see strength in communal stories and shared identities but now it is time to examine how our communal stories and our shared identities are incompatible with these deterministic types of identity politics. For me, our heritage is not defined by what happened to us or, even worse, by what ‘they’ did to us; I see us as being defined by how we acted in those circumstances. When the time came to say no, we said no; when things went too far, we pulled them back; when they attacked us, we stayed strong together; and when they denied us justice, we did not give up the fight. Yes, we have swallowed a lot of “bitter pills”, as mentioned in the article I felt compelled to respond to here, but those bitter pills are not the focus of our gaze when we peer into the past. Instead, we are searching for and leaning on the common strength we found within ourselves to swallow them and keep going, together. It is not the Hillsborough disaster that defines us but the decades-long fight for justice.

‘Yes, we have swallowed a lot of “bitter pills”, but they are not the focus of our gaze when we peer into the past. Instead, we are leaning on the common strength we found within ourselves to swallow them and keep going.’ It is not the Hillsborough disaster that defines us but the decades-long fight for justice.’

Our heritage is built upon solidarity and standing together in the face of adversity. Yes, the idea of being “Scouse, not English” stems from a long history filled with gunboats on the Mersey, contrition over our role in the slave trade, and solidarity and action in the face of marginalisation, but I believe making our identity political in nature would be incompatible with the ties that bind us.

This is because a key point here is that our stories mustn’t simply be cartoons and scare stories to tell our kids. There needs to be substance behind them for them to have real meaning. Yes, Thatcher is a scary spectre from our past, but it is because of the real actions she took against the city. Managed decline was real and, in many ways, with central government commissioners overseeing the city right now, it still is. It’s not enough to simply go on about Thatcher; the people of Liverpool must stand for what she was trying to stamp out. Her war on society in support of international finance and global market forces tore the country apart, but in Liverpool, we stood strong and fought back against the propaganda levelled against us and our neighbours. There is no need to mention Murdoch’s rag by name, but by turning our back on the hate it peddles we have set ourselves apart in hearts and minds from our compatriots who are more readily exposed to the bile it spews.

Therefore, despite our unique perspective on the British experience, it is what we must stand for that means the notion of being “Scouse, not English” can only take the people of this city so far. An independent scouse republic on the banks of the royal blue Mersey, although intriguing to imagine, would be hard to square with our relationship with justice. To pull ourselves apart from neighbours who have shared our hard times would be to abandon them to the malicious will of a common tormentor. Yes, we can celebrate who we are and shine a light on the transgressions of the state but when it counts, we must stand together.

Finally, it is important to reiterate that our stories from our past couldn’t be more relevant to our future and the challenging times that lay ahead. We need the strength they give us and dare I say it, people up and down the country need it too. The community spirit needed to stare injustice in the face and stand for what is right, no matter the odds. We can’t and shouldn’t turn our backs on that now. We’ve been here before and as a city, we are stronger for it. If it is a question of image, then we should own it. The message should be don’t feel sorry for us because of the difficult times behind us; we own who we were, who we are, and who we will be. In fact, don’t worry, this city, for all we’ve been through together, is here for you. The difficult times we have experienced as a city equip us to help anybody who needs it with the difficult times ahead that we all will share.

Patrick Devaney is from Liverpool but lives in Barcelona, Spain where he works as Editor of the Digital Future Society Think Tank. He also works as a consultant for UNESCO on the digital transformation of education. You can tweet Patrick at @PatrickDevaney_ or reach out to him on LinkedIn.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Why we should stop banging on about Thatcher and the Toxteth Bloody Riots

Journalists arrive in Liverpool to tell the same story over and over again - the city cast as the lead in a Shakespearean morality play, fuelled by righteous anger, touched by tragedy, let down by treachery. Yet is our own obsession with the 1980s feeding the media stereotypes?

Paul Bryan

My personal experience of the 1981 Toxteth Riots existed, as for so many others in Liverpool, solely on television. The nightly news reports showed lines of police officers cowering under shields as youths hurled stones and set light to cars and buildings. I didn’t know why it was happening but I knew it was exciting and so did my friends – as if through some mechanism of the collective unconscious we quickly turned it into a street game, unimaginatively called ‘Toxteth Riots’. The rules were fairly simple. All you had to do was clutch a metal bin lid and defend yourself from rocks and stones hurled somewhat half-heartedly by your mates. The winner was the one who could stick it out for the longest. Writing about this now, I’ve only just realised, we were instinctively putting ourselves in the shoes of the police. They at least seemed understandable. Still, it didn’t hold our attention for long. We got bored of it after two nights.

If only I could say the same about the national media. 41 years later and they’re still using the Toxteth Riots as the go-to framing device for just about any story on Liverpool. Of course, in no way do I mean to belittle the experiences of those who were there, or those who suffered under the social forces that made life more difficult. But for me growing up, the riots always felt like something distant, from some other Liverpool, far off and largely irrelevant. If anything, the Toxteth Riots were a boon – they gave me the chance to meet TV scarecrow, Worzel Gummidge at the International Garden Festival three years later, thanks to the intervention of Michael Heseltine, unofficially crowned the Minister for Merseyside.

I mention this personal story because I’ve noticed a tendency in the media and in political circles to describe Liverpool as a single unit, with a single, monolithic outlook and I find this approach unhealthy and untrue. The Toxteth Riots as history and metaphor have become something of an unquestionable foundation stone in our understanding of Liverpool’s journey. I’m not for one minute doubting their significance, but merely wish to flag that, due to the vicarious nature in which they were experienced by many, the events will never speak to us all in the same way and I think that’s worth acknowledging given the sometimes over-simplified, stripped-down caricature of ‘Scouse’ tales that we are often encouraged to identify with. And if that applies to someone who was alive at the time, you can bet it will apply even more to those who were as yet unborn.

The Toxteth Riots sit as the starting point of a master narrative that is told and retold ad finitum. Typically, it’s a story pitched as one of strife and rebirth – a city on its knees rising phoenix-like from the ashes with the regeneration that followed. Either that or it’s used to evidence our home town’s long history of racial inequality. There are further beats in the story of course and usually they point to ‘basket-case’ – a city that just can’t seem to catch a break or get its house in order. A place that is frankly perplexing. Journalists visiting Liverpool tell the same story, time after time, yet they never tire of it, new facts on the ground serving merely to embellish an already familiar pattern.

It would be easy to point the finger at outsiders here, but this game plays out amongst Liverpool’s inhabitants too and I’ve begun to wonder… does the incessant focus on the 1980s (and we must throw the hate figure that is Margaret Thatcher into the same pot) does the constant repetition serve the city’s best interests? Do these references still yield insight or are they just a reheating of old battles, about as useful to understanding Liverpool today as the Suez crisis is to making sense of Britain’s contemporary approach to foreign policy?

A case in point. This week, the Mayor of Liverpool, Joanne Anderson was interviewed by a journalist from the left-leaning New Statesman magazine, enticed no doubt by the city’s hosting of the Labour Party Conference. Ostensibly about Liverpool’s current political crisis, the article began like this… “In 1981, the violent arrest of a young black man near Granby Street in Toxteth, Liverpool, led to nine days of rioting.”

“Journalists visiting Liverpool tell the same story, time after time, yet they never tire of it, new facts on the ground serving merely to embellish an already familiar pattern.”

What followed was a tick list from the unofficial media guide to Liverpool which we presume is handed out by the NCTJ on journalism graduation day. Margaret Thatcher, ‘managed decline’, European Capital of Culture and the regeneration of the Albert Dock, Derek “Degsy” Hatton and the Militant Tendency, gang warfare and the shootings of young children, now sadly updated with new names. Welcome to Fleet Street’s version of Punxsutawney where we’re all doomed to live the same day, every day. Bill Murray, at least, found a way out. In Liverpool, we’re still looking.

Truth is, the story could have been about anything – crime, the opening of an arts festival, or an important football match and it could have been published anywhere – The Telegraph, The Guardian, The New York Times or Unherd. It doesn’t really matter what the initial prompt is, as long as the story stays the same. Liverpool, the city, is perennially cast as the troubled lead in a Shakespearean morality play, fuelled by righteous anger, touched by tragedy, let down by treachery, now sadly a watchword for – (insert your favoured macro-political, agenda-driven blank here).

Refreshingly, the Mayor was not too impressed with the New Statesman article. On Twitter, Joanne claimed the writer had “focused on a whole load of scouse stereotypes” and accused him of “lazy journalism”. I found myself in agreement so I reached out to the Mayor for further comment, and to my surprise she replied. What she had to say, for a local Labour leader is, I think, important and worth hearing. But you’ll have to wait a while. You see, first I have this theory and it involves turning our attention inwards. It’s the real meat in this piece. For as much as we might want to blame the media, I believe that the press are, in large part, reflecting back what we as a city put out about ourselves.

Sometimes, our own worst enemy

Compare these two statements. The first is by a journalist, Oliver Brown, Chief Sports Writer at the Telegraph, who was writing about Liverpool’s complex relationship with the establishment in light of some fans failing to observe a minute’s silence to mark the death of the Queen.

“Liverpool is a city that feels that it has been shunted to the margins of British society. It is scarcely an unfounded view.”

The second is from Kim Johnson, MP for Liverpool Riverside who was describing her sense of betrayal at Labour Leader, Keir Starmer writing in the Sun in 2021.

“We are the Socialist republic of Liverpool, a city that marches to the beat of a different drum, a resilient city that will always come back fighting. But we have a long memory and will not forget this betrayal by the leader of the Labour Party, in our Labour city.”

Can you spot the similarities? For starters, they are both quite careless in their use of the collective – back to that sense of the monolithic, singular opinion to represent the Liverpool way. But they also both spoke to something else – a powerful sense of grievance baked into the city identity. Kim Johnson’s quote in particular was the perfect crystallisation of a view that has become increasingly noisy in recent years – the idea that Liverpool is ‘Scouse, not English’ – a place apart, waged in a perpetual battle to get a fair deal, coalescing around some sense of the ‘Other’.

A few weeks back, the Liverpool Echo’s Dan Haygarth, in a quite remarkable article, attempted to explain why so many in the city reject national identity. As explanations go it was comprehensive, yet strangely unconvincing, but it was a perfect reflection of what passes for common sense around here. Supposedly, our 19th-century Irish roots had turned us into ‘rebels’ sceptical of authority; our coastal location transformed us into natural internationalists who looked out rather than in; a history of being ‘let down by the establishment’ first by the Thatcher government in the 1980s and then over the Hillsborough disaster had for many ‘broken the city’s relationship with England beyond repair.’ Throw in the generosity of EU European Objective 1 funding followed by savage post-2010 cuts from Westminster, a Brexit vote that went the wrong way and a nasty article in the Spectator under Boris Johnson’s watch and a seemingly irresistible case was made for a city destined to walk alone.

Haygarth’s article concludes – “The phrase 'Scouse, not English' not only encapsulates Liverpool's civic pride and a healthy rebellious spirit, but expresses a feeling that the city has been so often let down by the establishment of this country. It should come as no shock that large swathes of this Labour-voting, outward-looking, and heavily-Irish city do not feel like they have much in common with the rest of England.”

“They also both spoke to something else – a powerful sense of grievance baked into the city identity… a mutual connection made through the collective swallowing of bitter pills… our loudest voices complicit in the forging of our own myth of alienation.”