Recent features

Face Value: What makes a good council?

Are diversity and representation the most important determinants of a good council? Reacting to our previous article, Child Labour, Liverpool’s Lib Dem Leader Richard Kemp, the city's longest standing councillor, leans on his years of experience to explain what he thinks makes for a successful council chamber.

Richard Kemp

There have been a lot of comments on the Liverpolitan Twitter feed recently after they published Child Labour, an article about the number of young councillors coming on to the scene in Liverpool.

I was struck by the defensive nature of some of them especially from those who had been elected as young councillors themselves. Yet no-one has suggested that young councillors are a bad thing. They can offer a viewpoint and an energy that older members of the chamber might struggle to bring. A good council will use the knowledge and energy of young people as part of a balanced team where their voices can be heard rather than dismissed as it so often is.

I thought that I might contribute to this discussion because although at 69, I’m clearly not a young councillor, I was once and my experience of moving through the ages might help the debate. I was first elected at 22, became the equivalent of a Cabinet Member at 24, and after 39 years in office, I’m now the longest serving councillor in Liverpool. In a variety of roles including as national leader of Lib Dem councillors I have supported elected members in more than 50 councils across the country so I’ve seen a lot of local government – both the good and the bad.

This experience does hopefully give me a long-term perspective from which to answer two related questions which I want to address - ’What should a good council look like?’ and ‘What does a good councillor look like?’

So to the first question. In a nutshell, a council should look as much as possible like the people of the area it represents. This applies both to the elected side of a council and also to its workforce, but in this article I’m just focusing on the elected side.

“When choosing candidates we have to be looking at factors like gender balance, ethnicity, age and class. Does what’s found in the chamber reflect what’s found out on the streets?”

Why is this important? Because having a diversity of councillors means that there is a diversity of knowledge and experiences within the council chamber. Different groups of people are impacted by decisions in different ways so having broad representation ensures that we keep our eyes open and our hearts sensitive to the different priorities of the groups that make up our population. That’s really important because even if our intentions are good as councillors we can’t presume we understand everything or even feel everything that is important to our electorate.

For example, I have never been discriminated against on the grounds of race, gender or sexuality. I can empathise with those who have and have a feeling for their challenges but I do not have that direct experience. Perhaps it’s the same with generational differences. I wasn’t born into the computer age, so I don’t have that instinctive feel that younger people do when discussing the challenges of technology, the industries of the future, the pitfalls of social media and issues around how we best communicate with each other. Ultimately, each person has their own stories to tell, and the better our representation, the more able we are to harness them to improve policies and more effectively monitor their success from different perspectives.

All of this means that when choosing candidates to stand for our parties we have to be looking at factors like gender balance, ethnicity, age and class. Does what’s found in the chamber reflect what’s found out on the streets? It’s worth looking at some of the available statistics. In Liverpool, according to the last census data 51% of our population are female and 49% male, while about 14% are from ethnic minorities including those born in other countries. A wide range of faiths are represented. Our population trends slightly younger than the national average with the under 30s clustering in the centre and average ages increasing as you move outwards especially to the north. When you start to look at profession and class, manual workers now make up a smaller proportion of our elected officials compared to when I first became a councillor, but that reflects changes in the city and society as a whole. The age of mass employment in big unionised factories like Tate & Lyle, Ogdens Tobacco, Dunlop, Courtaulds or, of course, the docks is long over, a decline which set in many years ago as computers and mechanisation took over.

Liverpool Council is currently completing a survey of councillors but the last one, conducted five years ago, showed that only 40% of elected members were female. However, the last five years has brought about a big change in that figure with Liverpool now one of the few councils in the country to achieve gender parity. We appear to have made less progress in other areas. Later this year we will have access to the first results from the 2021 National Census. This will provide us with the most up-to-date information about the make-up of the city’s population compared to that of its councillors. Those results should prove useful as we continue to try to improve representation.

Councillors from Liverpool and the Wirral had their say on our article, Child Labour

However, and this is an important point, diversity is not enough on its own. Having elected members that look like the community does not mean they’d make inherently better councillors. Being a councillor involves passion and compassion; with a strong civic desire to serve the community. It involves commitment. It involves hard work. Being who you are is only the start. It’s what you want to do and how you want to do that counts and it takes a council chamber full of people with vision and ability to make a good council that is both representative and capable.

If we turn our attention to the second question, ‘What does a good councillor looks like?’, we can see why the ideal council is difficult to create. Your average councillor has four calls upon their time. In addition to what can be the hard and demanding grind of the job of councillor, they also need to earn a living, care for their family and help run their political party which usually involves a lot of campaigning and canvassing. Juggling these different demands is a challenge and the level of difficulty lands differently on different people effected by things such as time of life, financial security, responsibilities for others and many other factors.

Being a councillor in a big city like Liverpool is a particularly arduous task if you do it properly and most councillors of most parties do. The life of a councillor involves attending council and committee meetings, keeping up-to-date with the constant stream of information and documents, coordinating with other councillors from your political group, and undergoing professional training when necessary. And all the while you are trying to weigh up matters, figuring out what decisions you have to take, and the need to make decisions is continuous. We then have to work within the communities that we represent, fact-finding and campaigning alongside the many volunteers who keep community life ticking over. For many of us council life is almost 24/7 and 365 days a year.

It’s worth noting that councillors do not receive a salary. Instead they receive a basic annual allowance which is worth £10,590 plus expenses. Those councillors who have additional responsibilities such as Cabinet members receive additional Special Responsibility Allowances (SRAs) but of course, many do not. This means, that most have no choice but to work for a living. Very few employers like the idea of a member of their staff being a councillor. The fact that we can legally demand unpaid time off to a certain level is unattractive to many which is why councillors often work for the public sector, unions or choose to be self-employed.

Outside of work, councillors have families and face the same pressures as the rest of the population. Those with added responsibilities such as caring for ageing parents or young children will inevitably have more on their plate than those who aren’t dealing with such issues. This is of course not unique to councillors but it’s worth noting because for some perfectly able individuals it can be an impediment preventing them from running for office or continuing their work once elected. In my experience, it’s easier to find the time to do things when you are a grandparent rather than when you’re weighed down with the challenges of parenthood.

Finally, all councillors except perhaps independents have to work inside their own political party undertaking political campaigning and policy development not only for local but also for national elections. What will surprise people who always think of us as politicians, is that party work often takes up a very small percentage of our time. More often than not, we tend to think of ourselves as councillors and not politicians.

All of these four factors intervene at different times to affect what we can do as councillors and even whether we can continue to do the job.

In future, if we want a more representative council we need as an organisation to understand the realities of these four competing pressures on councillors and provide support mechanisms to help people cope with them. For example, there’s a carers allowance whereby councillors with young children can get some support for childcare activities but none for those who have to care for relatives either older than themselves or those with physical or mental needs.

“The question of money gets raised from time to time. Some believe councillors should be paid more to attract better candidates. I don’t think that more money would actually change the makeup of the council, nor should it.”

I often mentor Lib Dem council groups and young people who are thinking of standing for office or even sometimes those who have been already been elected and they often ask me if I think being a councillor is a good idea. My answer is invariably, “Yes, but think through what that will mean to you and yours.”

Being an elected representative is a huge learning experience which we often fail to capture. On the job, I learned how to speak in public, how big organisations work and how to work effectively within them. I developed many skills in political and managerial leadership. I also picked up a lot of knowledge about people, communities and the way that the public sector responds to needs and problems.

I was lucky enough to find a job as a regeneration adviser which made use of those skills and knowledge sets. That was, however, by luck not judgement and no help was given to me to find work that would utilise my hard-earned experience. I think a major way forward for all councillors, except for old gimmers like me, would be to find a way of accrediting the learning experiences and training that we have acquired. Having people who know how the public sector works, can chair meetings, can speak in public, and understand how to interpret balance sheets and trading accounts should be a very attractive proposition for both public and private sectors if we could capture that and enable us to put it on our CVs.

For very practical reasons there are life factors which will inhibit the very young and very old from being councillors. Most young people want to experience life in a range of educational, work and leisure activities before settling down. At the other end of the timeline, I am finding it increasingly difficult to cope with some of the grind of council work. I can now only deliver leaflets for 2.5 hours before the knees go!

But saying that, there is an advantage to being an ‘old hand’. I have developed a deep well of ‘life experience’, some of it gained though my time at the council, but much of it elsewhere. I’ve learned how to listen, how and when to intervene, how to make a point and when it’s better to keep my mouth shut. I now have the confidence to know that I know a lot, but also that it’s OK to admit that there are areas where I know little or do not have the skills required. Always strive to surround yourself with great people – you don’t have to be an expert in everything.

The question of money gets raised from time to time. Some believe that councillors should be paid more to attract better candidates. I don’t think that more money would actually change the makeup of the council, nor should it. When I was first a councillor, we only received an allowance of £10 a day which wasn’t a lot of money even in 1975! But it didn’t affect my desire to do the job. You have to do it because you care and because you feel that being a councillor is your way of giving back to the community that you live in.

I’ve had a great deal of pleasure and satisfaction from my years as a councillor, but it has never been an easy job. When people tell me I am not doing enough of this or that or spending my time wrongly, I always challenge them to stand for the council themselves. Being an angry couch potato or keyboard warrior is much easier and few take up the challenge.

Most councillors of all parties do their best. Everyone can help us to do our job better by supporting us with their time and knowledge in a positive way. If you want more good councillors think of ways in which you could help the ones you’ve got now – that is if you are not prepared to put yourself to the electoral test!

Richard Kemp is the longest standing councillor in Liverpool. He is also the Leader of the Liverpool Liberal Democrat Group.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Child Labour

The latest local election results confirmed an ongoing trend – Liverpool’s councillors are being recruited at an ever younger age. But with low turnouts and widespread voter apathy, what does the emergence of ever more fresh-faced political candidates say about the health of Liverpool’s political culture? And should experience and proven competence trump youthful enthusiasm?

Michael McDonough and Paul Bryan

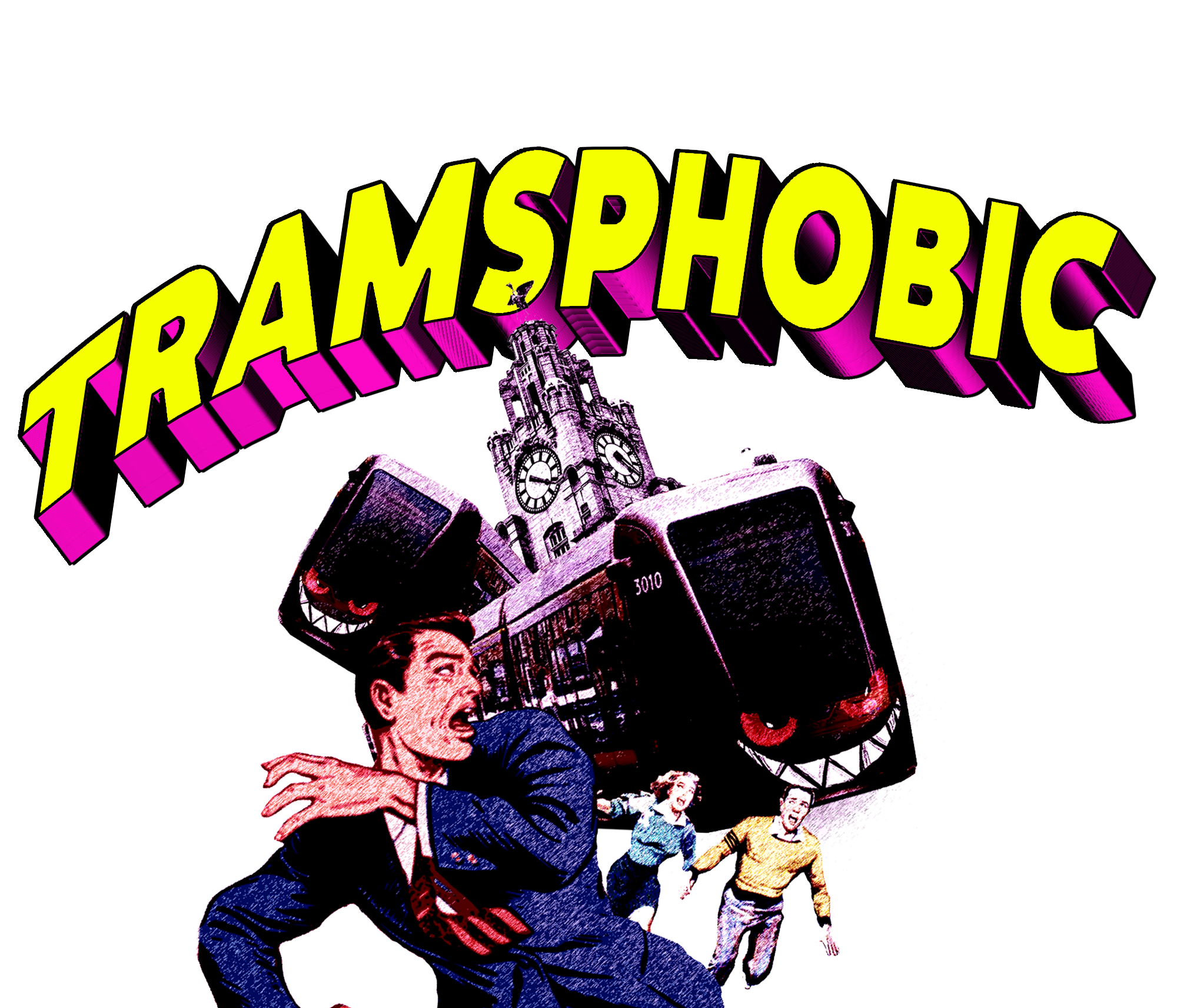

The latest local election results have confirmed an ongoing trend - Liverpool councillors (especially Labour ones) are being recruited at an ever younger age.

Sam East (Warbreck) and Ellie Byrne (Everton) both in their early twenties, join the likes of Harry Doyle (Knotty Ash), Frazer Lake (Fazakerley) and Sarah Doyle (Riverside) who became councillors at ages 22, 23, and 24 respectively (give or take the odd month – feel free to correct us). The latter three are now all serving in senior positions as part of the Mayor’s Cabinet.

Labour are not the only ones playing to this trend though. On the Wirral, Jake Booth, 19, took a seat last year for the Conservatives while in Liverpool the Tories recently appointed the frankly mature in comparison, Dr David Jeffery as their Chairman at the ripe old age of 27 (though he’s not a councillor).

The emergence of ever more fresh-faced local political candidates, which is often presented as energising and key to connecting with the city’s younger generation is nevertheless curious. Traditionally, solid life experience and proven competence in some other field of endeavour have been seen as valuable traits essential to making a decent fist of a job in public office. Demonstrable skills and previous success, which take time to accrue, have acted as a semi-reliable predictor that a candidate will land on their feet. But that kind of thinking is out of fashion. A fresh, young face is the recipe de jour.

Except it doesn’t seem to be working. The turnouts in the latest by-elections were abysmal- the puny 17% turnout in Warbreck putting the even more atrocious 14% in Everton to shame. Perhaps this should be a lesson that viewing politics though the lens of identity resonates far less than actually being credible.

None of this is to suggest that young people shouldn’t be in politics - far from it! And you could argue the older generation haven’t exactly pulled up any trees. Age and ability are not guaranteed bedfellows and we’ve all met unwise old-hands who are best left in the stable. But surely, even amongst the parroted outcries of ageism, track record counts for something?

The comments in the Liverpool Echo were a peach. “Shouldn’t those two be in school?” said one. “What life experiences can they bring to their roles. Jesus Christ!” said another. L3EFC expressed some doubt that “People fresh out of Uni” would be able to “stand up to the people who grease the wheels in this town.”

Which means we have to ask the question… can it be right that such inexperienced councillors are representing these deeply challenged areas which are crying out for leadership that can deliver on the ground? Will Councillor Ellie Byrne, the daughter of a sitting MP, deliver the kind of positive change Everton desperately needs? Does Councillor Sam East have the real-world nous to effectively tackle the issues holding back Warbreck? Or are these two eager and no doubt able politicians the product of a disinterested local Labour machine that doesn’t care or need to care about who it puts forward for election?

“The comments in the Liverpool Echo were a peach. ‘Shouldn’t those two be in school?’ said one. ‘What life experiences can they bring to their roles? Jesus Christ!’ said another.”

Of course, there are several reasons why young candidates are so attractive to party leadership. On the upside, they offer the classic and generally much needed injection of new blood. They hold out the potential for new ideas and new energy. And in Liverpool, where there is a dark shadow over much that has gone before, you can understand the desire to clear the decks and start afresh. But there’s another darker reason. Young councillors are pliable. They’re more likely to do what they’re told. While they’re still building their confidence, they won’t challenge the top dogs and that’s useful when your grip on power is weak. Mayor Joanne Anderson, herself relatively inexperienced as a councillor, has introduced young members to her Cabinet with responsibility for key portfolios including Development and Economy, Adult and Social Care, and Culture and Tourism. Without casting any aspersions on Cabinet members talents or potential, you can see their appeal.

We have to ask where the Liberal Democrats, Liberals, Conservatives and Greens are in all of this? Despite making admirable gains in many wards they still haven’t made much of a dent in the city’s ‘red rosette’ Labour strongholds and this despite the Caller Report offering them ammunition on a platter. As strong a campaign as the Green Party’s Kevin Robinson-Hale ran in Everton (albeit clearly under-resourced) he still only polled 362 votes. In Warbreck, the Lib Dems Karen Afford polled 874. This is not what engagement looks like. Perhaps it’s time all parties in the city took a long hard look at who they’re putting forward for local elections, what pledges are being made and why for the moment so many amongst the electorate simply couldn’t give a toss about what their local political parties have to say.

Ellie Byrne’s vacuous election promises were a case in point and a classic example of how an unengaged electorate enable party cynicism. Why bother getting too specific or measurable with your commitments when no-one is asking for it might be the rejoinder of the spin doctors, but it feeds the descent into low participation. A deeper critique suggests a more existential worry – our parties just don’t have any answers, scraping around in the bargain bin of ideas, and plucking out little more than platitudes of intention. Heaven forbid someone might actually come up with a plan to drive more employment.

It must be said in Liverpool the wheels turn more slowly. Many voters’ unflinching loyalty to party blinds them to individual failures, provoking little more than a shrug of resignation. Or worse, it depresses their sense of the possible. And that’s deadly, because if you don’t believe you can do much in life, the world has a tendency to deliver on your expectations.

But you can only hoodwink the voters for so long. When it comes to delivering results in the four years of office a councillor receives, competence beats willing nine times out of ten. A fresh face may serve you well enough amongst the cheap thrills of an election campaign, but does it really get the job done? Eventually, without the ideas or the know-how to deliver on them, you’ll get found out.

There is the temptation in Liverpool to think that little changes in the political sphere. That despite the odd bit of noise within the ruling party, on the outside all is stable and unchanging. A recent electoral modelling exercise suggested the upcoming 2023 boundary changes in electoral wards would have only the most superficial of effects. Labour, instead of holding 78% of council seats would now hold 79% it predicted. So much for turbulent times.

But bubbling away under the surface, something is happening and the results will be unpredictable. The recent by-elections were a warning, not just to Labour but to all parties. Sooner or later, voters will do what voters do. They don’t like being taken for granted.

All of this opens up a wider question about the city and its communities. Why are there so few people from a more professional background standing for election? What exactly is turning them off? Many of these people will be successful in their own lives. Could there be some really strong politicians and visionaries amongst the roughly 70% who don’t vote in local elections? Are there talented leaders amongst those Liverpolitans who look on at an unwelcoming, opaque and sewn-up political culture with distaste and disengagement?

Decades of brain-drain have undoubtedly had an impact. Liverpool has jettisoned so much of its professional class who left in search of opportunity they could not find at home. And now the parties are trying to fill the void by turning to ever younger graduates. If the trend continues we may well see in the coming years candidates organising their election campaigns around their GCSE examination calendar. An 18-year old Jake Morrison, who triumphed in 2011 over former Council Leader, Mike Storey to win the Wavertree seat may have well been a harbinger of times to come. He retired from politics aged 22.

Of course, at Liverpolitan, we always wish newly elected councillors well and hope to be pleasantly surprised by the new additions but we’d argue their election success is symptomatic of a much bigger elephant in the room, a room that clearly has fewer and fewer adults. It is a room dominated by established party complacency and a dash of arrogance; a city electorate detached from politics and a political culture devoid of real local talent and energy putting itself forward.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

How should we be governed? Six parties have their say…

The Council’s public consultation on future governance models for Liverpool is now open and at Liverpolitan we think you should get involved. But what’s the position of the parties? We asked six of them – Labour, Liberal Democrats, The Green Party, The Conservatives, The Liberal Party and the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) to write up to 400 words stating which of the three governance models they favour and why.

Liverpolitan

Well, we might not have got the referendum we wanted but the people of Liverpool still have a chance to have their say on how the city is run. The Council’s public consultation on future governance models is now open and at Liverpolitan we think you should get involved.

Healthy democracies require participation and in a city that often sets a high bar on shenanigans, figuring out how to keep our representatives and over-lords in check and on-track seems like a worthwhile way to spend our spring evenings.

So what do you need to do?

Visit https://liverpoolourwayforward.com

Read about the three options on the table, weigh up the pros and cons, talk to your friends and family, have a row about it, and complete the online survey by no later than the 20th June 2022.

The three options presented are:

1) The Mayor and Cabinet model – what we have now

2) The Leader and Cabinet model – what we had previously

3) The Committee model – what we had before the year 2000

Once the results of the consultation are in it’s then up to our councillors to decide how or indeed whether to implement the results. That may leave wiggle-room for all kinds of disagreements but there’s a strong suggestion that parties will attempt to honour the outcome. Any changes that take place will be implemented from the 4th May 2023 at the local elections.

But which models do each of the parties support?

We asked six local political parties – Labour, Liberal Democrats, The Green Party, The Conservatives, The Liberal Party and the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) to write up to 400 words stating which of the three governance models they favour and why. Each party either has local councillors in Liverpool now or in the case of the Conservatives and TUSC regularly field candidates in local elections.

Here’s what they had to say.

The Labour Party position

We approached Major Joanne Anderson for comment but did not receive a reply, although in a previous interview on BBC Radio Merseyside she said “I want to say neutral." However, an official party spokesperson gave us this statement:

by a Liverpool Party spokesperson

“The city wide consultation is now open and the Labour Party is committed to listening to what the residents of Liverpool have to say about how the City Council is run. It is important that no political party pre-judges the outcome of the consultation and that residents feel that that their voices are being heard. Based on the results of the consultation, the Labour Party will then take a formal position on the governance of our city.”

Model favoured: Undecided

Liverpolitan says: Labour’s position is not to have a position until the results of the consultation are in. They will then decide on their favoured model ‘based on the results’.

The Liberal Democrat position

by Councillor Richard Kemp, Leader, Liverpool Liberal Democrats

The ‘committee system’ is the Lib Dem choice for Liverpool’s governance

“There are three choices allowed in law by which the council can govern itself although some modifications can be made to the Leader and Committee models.

“I am working on the assumption that few in Liverpool would be mad enough to vote to keep the Mayoral system as it has been so badly devalued by Joe Anderson.

“The Leader and Cabinet model has many of the bad mechanisms that are contained in the Mayoral model. Much has been made of the fact that this is the model that the Lib Dems introduced in 2000 but we had little choice because the only two options that were available to us were the Mayoral or Leader models. Both of them concentrate power in the hands of a few people and do so in a way which encourages secrecy and makes it very difficult to challenge what the Cabinet wants to do. The Leader model was the least bad option!

“Since 2012, a third way has been available which is called the Committee system. This means that decisions are taken not by a one-party cabinet but by a number of committees which are representative of the political make-up of the council. That means that:

1. Decisions can be challenged at the time they are made by members of both the biggest party and the other parties on the council.

2. All councillors will be involved in decision making which means that they will know more about what is going on and have to account for the decisions that they make to the people.

3. The people of Liverpool will be more involved as well because there are far more people that they can ‘nobble’ about these decisions.

4. The system is much more accountable and transparent with far fewer decisions being made in the dark recesses of the council.

“We believe that this is the best way forward and will campaign for it in the coming months. However, there is no point in consulting with the people of Liverpool unless we are prepared to debate the issues with them and take heed of what they have to say. We hope that a clear expression of what people want will come out of the consultation. We will then support the people’s views and I challenge the other parties to do exactly the same.”

Model favoured: The Committee system

Liverpolitan says: The Lib Dem’s position is clear – they will be campaigning in favour of a Committee structure of governance but promise to abide by the results of the consultation.

The Green Party position

by Councillor Tom Crone, Leader, Liverpool Green Party

Democratic decision-making for a cooperative political culture

“We are very critical of this consultation. Once again, the people of Liverpool are being denied a proper say on how we are governed. In 2012, while voters in cities across the country were asked if they wanted an elected mayor, Liverpool Labour decided they knew best and imposed the mayoral model. The result was a decade of chaotic mismanagement. Now the city council is having to work round the clock trying to fix the mess left behind.

“This consultation does not have the same democratic authority as a referendum. Having three options makes a clear, unambiguous decision unlikely. The responses will need interpreting, and that will still leave the final decision with the Labour Party. That has a nasty whiff about it. We would much prefer to trust the people of Liverpool with the final decision.

“The Greens will be making the case for adopting the committee system. The committee system involves many more councillors in decision making and policy development. Under the current system even most Labour councillors have very little to do with real decision making. It is only Cabinet members who have real executive powers. Other democratically elected councillors are simply shut out. Even within the Cabinet, the Mayor sets the agenda and can predetermine outcomes. Power is really concentrated in a very small number of individuals. This leads to poor decision making, not least because it fails to make use of the skills and experiences of all the 90 councillors elected to represent their communities.

“The committee system, as well as sharing out power more fairly, also encourages much more constructive cross party working. The public rightly complains about “yah-boo” politics and it is shocking how often our debates in council chamber descend into pointless political point-scoring because really decisions are taken elsewhere. A committee system means different parties having to sit down together and really decide how best to deliver for the people of Liverpool. Councillors will soon realise that they agree on a lot, while learning to respect distinctive perspectives.

“The imposed Mayoral system opened the door to the shame of the Joe Anderson years, and slammed it shut on transparency and democratic accountability. It’s time to ditch the personality politics and let the people back in.”

Model favoured: The Committee model

Liverpolitan says: The Green Party’s position is clear – they will be ‘making the case’ for a Committee structure of governance.

The Conservative Party position

by Dr David Jeffery, Chairman, Liverpool Conservatives

The voters should decide whether we have a Mayor, not Liverpool Labour

“In 2012, referendums were held across 11 of England’s large cities on whether to introduce directly elected mayors. One city was conspicuous by its absence: Liverpool. Instead, in their infinite wisdom, the Labour-run city council decided to ignore the people and voted to bypass a referendum. They introduced the mayoral position by stealth, and parachuted in Joe Anderson – and we all know how that turned out. Of the three authorities which have adopted and then subsequently abolished the mayoral system, all three have done so following a referendum. If Liverpool Labour get their way, once again one city will be conspicuous by its absence: Liverpool.

“The truth is that this Labour council want to ignore voters. This consultation is a gimmick – the result is a foregone conclusion, likely designed to sooth internal party arguments and resentments that have built up under Joe Anderson. We’re told by Labour that a referendum would be too expensive - never mind the fact that seven Labour councillors rebelled over Labour’s budget, which built up excessive financial reserves – but those more sceptical than I might argue it’s not a surprise that this move came after Labour were forced into a humiliating second round of voting in the 2021 mayoral election.

“Decisions on how our city is run should not be made from on high in Labour Party backrooms. Our executive arrangements should not be a consequence of internal Labour Party management. This city’s government is not their plaything, and to treat it as such is an insult to voters.

“There are good arguments for a Mayor: studies have shown that, compared to a council leader, mayors better represent the whole city, are more outward-looking, and are better at bringing much-needed investment into the city. Mayors are put in office by the people, whilst council leaders are selected in grubby back-room deals within their own party, and as such mayors have a better claim to speak for the city as a whole.

“Indeed, it is arguable that the real issues with Liverpool’s politics isn’t the mayoral system, but the fact that Liverpool Labour allowed Joe Anderson to abolish the mayoral scrutiny committee because he didn’t like the type of scrutiny he was receiving.

“Liverpool Labour should do the right thing and give the people of Liverpool a vote on how they are governed. It really is that simple.”

Model favoured: Undecided

Liverpolitan says: The Conservative Party have yet to take a formal position but do see merits in the Mayoral system. However, they believe that it should be up to the voters, not parties to decide which model to choose through the implementation of a referendum.

The Liberal Party position

by Councillor Steve Radford, Leader, The Liberal Party

Time to wake up. Keep the Mayor, adopt Proportional Representation and ask questions

“In over 40 years in politics I’ve seen corruption and abuse of power in all models of local government in Liverpool.

“In the Militant years I saw the sale of land at knock-down prices, council officers withholding information, dodgy minutes and record keeping and much more that I sadly can’t put into print. And that was under the committee system.

“Key to the abuse of council procedures was a willingness by some to turn a blind eye to those who broke or undermined the rules. Later on, during the Lib Dem years things were little different and legal battles had to be fought just to uphold the basic right of council members to attend certain public meetings. That was under the Leader and Cabinet model.

“One of the reasons I fear abuse of power has gone on for so long in Liverpool is the failure of the police to uphold the law. Today, they are tasked with some very important investigations under Operations Aloft and Sheridan that have been triggered during the years of the Mayor and Cabinet model. We should watch the outcome of those investigations closely.

“So what’s the answer? Firstly, we must get rid of the first past the post voting system than gives an inflated majority to a lead party, creating a vacuum of safe seats where the electorate is totally taken for granted.

“Secondly, we need senior council officers selected on merit, not on how subservient they are to the ruling party. Some have been brave enough to stand up for professional standards. Others have not.

“On to the Mayoralty. Without a doubt, both central government and the business community prefer a Mayor with an agenda focused on the whole city, rather than a Leader who is just accountable to a ward and their own political council group.

“Liverpool is an internationally recognised city and we need a Mayor to put us on a level playing field with our global peers. If Liverpool has in the past elected the wrong mayors that responsibility ultimately lies with the electorate. Being candid, it’s about time residents looked more at the person, and less at the colour of the rosette.

“Some readers may know that I chair the City Region Scrutiny Committee – and from that role I can see how the Metro Mayor, Steve Rotheram quietly secures funds for the region by adopting more mature and less confrontational politics.

“We should have a Mayor but we need a more diverse council elected by proportional representation, and we need a more curious electorate willing to ask difficult questions of the candidates who canvass for their votes.”

Model favoured: Mayor with Cabinet

Liverpolitan says: The Liberal Party position is clear – they support retaining the Mayor with Cabinet structure of governance, but want to see the adoption of city-wide proportional representation for local elections.

The Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) position

by Roger Bannister, Leader, Liverpool TUSC

Response to Proposals on City Governance

“Three proposals have been put forward on models for council governance in advance of the ending of the term of office for the directly elected Mayor in 2023, which are referred to as The Mayor and Cabinet Model, The Leader and Cabinet Model and the Committee Model. Of these three models, TUSC supports the Committee model.

“TUSC takes this position because it is the Committee Model that gives most powers to the directly elected councillors, rather than concentrating many of them in the hands of one person, as the Mayor and Cabinet Model does, or in the hands of a relatively small number of people as the Leader and Cabinet Model does.

“It is the strong view of TUSC that the electorate is best served when power is more evenly shared amongst councillors, so that by making representation to a Ward Councillor about an issue, that councillor will be able to exert influence effectively on behalf of the people that he/she represents. This is less likely to be the case with the other two models.

“It is our belief that both the Mayor and Cabinet and the Leader and Cabinet models were devised in order to ‘speed up’ the council decision making process, and whilst this is not a bad thing in itself, if it is done at the expense of democratic process, it is potentially prone to corrupt practice. Given the current involvement of the police in the municipal affairs of Liverpool, this point must be taken very seriously indeed.

“It is also our belief that there is a large and growing disconnection from, and cynicism in local politics in Liverpool, which can be expressed quite vehemently when people speak to TUSC candidates and supporters during election periods. The introduction of a directly elected Mayor, not as in most cities following a referendum, but by will of the Council alone, has done little to halt this trend.

“Local government in Liverpool is at a crucial stage, with democracy under attack both from the recommendations of Max Caller, with a reduced number of councillors, and elections only on a four yearly basis. Now is not the time to further reduce democratic accountability as the first two options would do.”

Model favoured: Committee system

Liverpolitan says: The Liverpool Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) position is clear – they support the Committee structure of governance.

So there you have it. Some for the Committee system, some leaning towards keeping the Mayoral model and some steadfastly neutral or yet to declare. But now it’s over to you. Each model has its advantages and disadvantages. What do you think?

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Liverpool Waters: Peel’s recipe for anytown, anywhere

The debates around development at Waterloo Dock and the expansion of John Lennon Airport were of totemic significance to the city of Liverpool revealing a schism between competing visions of our future. Progress and ambition pitted against tradition and conservation or so we are led to believe. But as Jon Egan argues, in the first of our new Debating Our Future series, there may be a third way.

Jon Egan

The debates around the Waterloo Dock project in Liverpool Waters and the expansion of Liverpool Airport caused heated debate amongst Liverpolitan’s contributors leaving plenty of room for disagreement. But one thing we all agreed on was their totemic importance to the city, revealing a schism between competing visions of our future. It’s a discussion the people of Liverpool need to have. What kind of place do we want to be? In this article, Jon Egan self-identifies with those sometimes christened as ‘nimbys’ and puts forward his idea for a city built around the cultivation of difference, individuality and beauty.

In the months ahead, we’ll explore these issues from other perspectives as part of a new ‘Debating Our Future’ series. If you would like to contribute to the discussion with your own vision, contact team@liverpolitan.co.uk

It's rare we embark on journeys in pursuit of the familiar, the ordinary or the humdrum. Travel, they say, is about broadening the mind, experiencing new sights, sounds, flavour and ambiences. The places we cherish and remember are those most imbued with a capacity to charm and surprise. So for places and cities aspiring to become destinations, cultivating and conserving what makes them different and original seems like a rewarding strategy. For Liverpool, a city that loudly proclaims its originality and inimitability, this should be a simple and unchallenging task.

When travel is neither practical or affordable, we always have the consolation of reading about the places we yearn to visit, experiencing their enchantment vicariously, though often with the added patina of poetic imagination.

Italo Calvino’s 1972 novel, Invisible Cities, is predicated on a series of imaginary conversations between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan. The famed traveller regales the Mongol Emperor with tales of the many fabulous cities he has visited, but true to the spirit of Calvino’s magical realism, these are not actual cities, nor even possible cities. They are extraordinary and fantastical creations - parables and paradoxes that explore what the book describes as the “exceptions, exclusions, incongruities and contradictions” that characterise and differentiate cities. Towards the end of the book, Marco Polo describes a city that heralds a disturbing vision, an incipient possibility foreshadowing the endpoint of globalisation.

“If on arriving at Trude I had not read the city’s name written in big letters, I would have thought I was landing at the same airport from which I had taken off. The suburbs they drove me through were no different to the others with the same little greenish and yellowish houses. Why come to Trude? I asked myself, and I already wanted to leave. “You can resume your flight whenever you like”, they said to me, “but you will arrive at another Trude, absolutely the same detail by detail. The world is covered by a sole Trude which does not begin and does not end. Only the name of the airport is different.”

The Waterloo Dock project in Liverpool Waters has totemic significance. For modernists it stands for ambition, progress and status. For the conservation lobby it was loaded with deep symbolism representing the destruction and the desecration of heritage.

So what, you may ask, does this have to do with Liverpool and its future? The answer lurks somewhere in the subtext of a recent planning controversy that divided commentators and communities, polemicists and politicians.

The project was the proposed residential development on the partially infilled Waterloo Dock in Peel’s Liverpool Waters. For modernists and urbanist thought leaders the project had totemic significance, standing as a shorthand statement of ambition, progress and status. For the conservation/heritage lobby the project was similarly loaded with deep symbolism representing the destruction and the desecration of heritage. The fractious debates and the absence of a shared narrative or vocabulary suggest a city without a clear or shared sense of self, insecure about its past and uncertain about its future.

The Romal Capital proposals for Waterloo Dock in Liverpool Waters were unanimously rejected by the Liverpool City Council Planning Committee on 18th Jan 2022. The developers have appealed and the plans will now go before the government’s Planning Inspectorate

So which side am I on? Typically perhaps for a Libra, both and neither. I have lamented the city’s lack of ambition, absence of vision and its inability to answer, or even ask itself, the fundamental question - what is Liverpool for? But I have also questioned the assertion implied, or explicitly asserted by some, that development is nearly always an intrinsic good. Indeed, in the context of the Waterloo Dock debate, I found myself aligned with alleged nimbys, and in spirited disagreement with many allies including the Editor and Founders of this publication.

Maybe the partial infilling of the dock and construction of an inoffensively bland apartment building was not the greatest ever crime against Liverpool’s heritage, but neither was this drably functional box of micro-apartments the most aesthetically or socially desirable addition to our (formerly) World Heritage waterfront. The debate and passions were evidently focused on bigger agendas and deeper sensibilities.

Fly-through video panorama of Waterloo Dock, Liverpool filmed in January 2022

Looming almost literally over the Waterloo Dock debate is a bigger picture, a grander vision and a development proposition that has insinuated itself into being a substitute for an actual future vision for our city. Liverpool Waters is now so ingrained into the city’s discourse and psychogeography that you could be forgiven for thinking that it actually exists. Peel’s near messianic promise to deliver Manhattan or Shanghai on the Mersey was proclaimed with a prophetic urgency in 2007, imbuing its curiously cinematic CGI’s with a hyperreal potency. When choosing between the actuality of World Heritage Site designation and the ephemeral fool’s gold promise of Liverpool Waters, we opted for the phantasy.

Liverpool Waters has both framed and constrained the debate about what sort of city we want to be, and what kind and quality of development we should be encouraging and embracing. Tall buildings have an obvious glamour. UK cities in particular seemed to be in frenzied competition to erect the tallest buildings, as if this, above all else, was a shortcut to status and significance.

Peel’s phalanx of waterfront skyscrapers was Liverpool’s trump card ready to be played (at some ceaselessly rolling future 30-year date), catapulting us ahead of our provincial rivals and reasserting our true global status. But is this what we want for Liverpool - a derivative identity, a replicant city? Trude on the Mersey?

Without for one second surrendering to nimbyism, we can recognise that imitation and simulation should not be our template. Echoing Calvino’s prescient warnings about globalisation, Desmond Fennell, the essayist and philosophical writer, foresaw similar tendencies at work in the early days of Ireland’s embrace of cosmopolitan modernity. In a beautifully evocative passage, in his book, State of The Nation, Fennell laments the loss of Dublin’s once rich and distinctive urban culture and soul. He mourns the curious and idiosyncratic details and delights that once defined and differentiated places.

Liverpool Waters is now so ingrained in the city’s discourse and psychogeography that you could be forgiven for thinking that it actually exists.

“If he is a Dubliner, walking amongst the offensive tower blocks, one who can cast his mind back 20 years, he will remember the vast Theatre Royal with its troupe of dancing girls, The Capitol and the old Metropole with their tearooms, Jammet restaurant and the back-bar, the incomparable Russell, the Dolphin, Bewley's and the Bailey as they used to be, the elegant grocers shops staffed by professionals of the trade, the specialist tobacconists with their priest-like attendants... It would be an exaggeration to say that consumerism destroyed or reduced the quality of everything: it improved the quality of tape-recorders, computers and inter-continental missiles and many other things. But it destroyed many of the amenities and much of the pleasure of cities, and, in a sense, the city as such."

The steady erosion of difference, character and defining originality is in danger of creating a sense of alienation and disinheritance as places converge and identities become eerily homogenous. We lose our bearings as familiar places lose their landmarks and legibility.

All too often progressives and modernisers have a tendency to disparage ‘conservatives’ whether they are rabid xenophobes or harmless nimbys, as people living in the past, fearful of change, trapped by prejudice and insecurity. But sometimes those who question change do have a point, even if it escapes rational or tangible articulation. Loss is something that is easier to feel than it is to explain.

So am I proposing a future constrained by conservation and suffocated by the cult of heritage? The simple answer is no, and if I may be excused for recycling New Labour nomenclature, I believe there is a third way. It’s an approach that can be radical, imaginative and ambitious without being imitative or simulatory. In a recent Guardian Op Ed, Simon Jenkins added his voice to the argument for diverse and differentiated strategies for regeneration.

“The Leaders of Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham and Bristol can think of no other way of competing with London than by erecting garish towers of luxury flats in their central areas. They ignore the evidence that modern creative clusters - in design, marketing, the arts and entertainment - are drawn to historic neighbourhoods and old converted buildings… Northern cities regard their Victorian heritage as a liability not an asset.”

For Liverpool this should not mean a moratorium on tall buildings or intelligent contemporary design, but it should be a challenge to rethink and re-prioritise. We know from our experience that innovation and regeneration are about more than large-scale physical development and shiny glass towers. It’s about what happens in the cracks and gaps, the higgledy-piggledy neighbourhoods and Wabi sabi spaces where innovators and pioneers just get on with it. So let’s learn the lesson from the Baltic and formulate a planning framework for the Fabric District before its character and urban ambience are swamped by more identikit apartment blocks.

The decline of our port economy has bequeathed us an enviable array of empty buildings and fallow dockland areas ripe for reseeding as creative clusters. But areas like Ten Streets need more than protective planning frameworks, they need assertive interventions and clever curation if they are to fulfill their potential. Where are the big catalytic ideas that would stimulate investment and clustering in an area that may otherwise remain a squandered asset? If we see Ten Streets as the incubator for a world-class digital cluster, should it also be the home for Liverpool’s equivalent of Paris’ Ecole 42 - the digital “university without teachers” whose model and approach is now being embraced by cities ambitious to expand their technology and creative sectors.

And what about Ten Street’s brash and status-obsessed neighbour? It’s time to radically reappraise Liverpool Waters. As a benchmark for ambition it’s looking increasingly hackneyed, irrelevant and unrealistic. Even its most impassioned advocates are now beginning to question whether Peel is seriously committed to actualising this Fata Morgana version of Liverpool's future.

The debate about the northern docks should not be a battleground between nimbys and tall building fetishists. It should be about what the city needs and how the immense potential of vacant dockland can be harnessed to make Liverpool a different and more attractive city for its people, its visitors and investors. In San Francisco the development brief for its historic piers (former docks) proposes a mid-rise human scale built form aimed at preserving the setting of the city’s downtown cluster - an important part of its visual signature - but also to safeguard the city's view of the bay and sense of connection to its port history. Far from fostering mediocrity, the city has encouraged architectural excellence and experimentation with brilliantly innovative contributions from Thomas Heatherwick amongst others. Ironically, this was the approach favoured by UNESCO as the basis for the future evolution of our World Heritage Site. It’s also an approach that would have facilitated a more seamless integration with Ten Streets and wider North Liverpool.

Sometimes those who question change do have a point, even if it escapes rational or tangible articulation. Loss is something that is easier to feel than it is to explain.

Of course, we need to recognise that regeneration of the city centre alone will never suffice; Liverpool’s individual identity resides as much in its suburbs and neighbourhood high streets, its stunning parks and rich Georgian and Victorian legacy as it does in the more showpiece locations. Prefiguring Calvino's parable, Marxist critic Guy Debord and his Situationist collaborators warned that the redevelopment of Paris in the late 1950s signified a ruthless process of rationalisation, commercialisation and homogenisation where the authentic social life of cities was being replaced by spectacle - "all that was directly lived has become mere representation." Like their Surrealist forbears, the Situationists saw the city as a playground or dramatic stage promising limitless encounters with the extraordinary and the unexpected (le merveilleux quotidien).

It seems strangely apposite for a city seduced by the film-set flimsiness of Peel's promise, that we cherish our architectural heritage less for its intrinsic quality - its lived experience - than its capacity to mimic more significant and glamorous places. Sure, we can take pride in being the UK’s most filmed city, but is that it? Is our identity founded on an aptitude for imitation and representation?

Peel's penchant for visionary masterplans extends beyond the stalled blueprint for Liverpool Waters. Equally "ambitious and aspirational" are its plans to transform our humble provincial airport into a global hub with direct links to long haul destinations on every continent. Irrespective of the merits, feasibility or environmental impact of the plan, it is another ingenious attempt to stroke the ego of a city short on self-belief and uncertain about its place in the world.

Proper cities have proper airports, and the fact that Manchester has one, is less a matter of convenience than cause for a deep seated inferiority complex. But as latter day Marco Polo, Bill Bryson’s descriptions of Manchester as “an airport with a city attached” and “a huddle of glassy modern buildings and executive flats in the middle of a vast urban nowhere,” reveal, mere status symbols are not enough to make a city significant or memorable. In contrast, Bryson observes that “in Liverpool, you know you are some place.”

We need a regeneration prospectus based on the cultivation of difference and individuality, that cherishes what’s unique, irreplaceable and above all beautiful, but also fosters experimentation and originality. We want Liverpool to be the conspicuous and refreshing antidote to the nightmare of endless and interchangeable Trudes.

Being “some place” is not a bad guiding principle for a city seeking to nurture difference, and be a place that people want to come to, and are in no hurry to leave.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Once Byrned, twice shy?

Ellie Byrne is Labour’s candidate for the upcoming council by-election in Everton Ward. Until recently, we’d never heard of her. But that surname sounded oh so familiar. And then it clicked. She’s the daughter of Ian Byrne, the previous incumbent turned MP and for some reason, Labour is avoiding making that connection clear. So who is she, what are her credentials and how, in a city that needs to play it straight more than ever before, did she win the nomination to represent Labour?

Paul Bryan

The upcoming council by-election in Everton Ward (April 7th) has thrown up an interesting wrinkle. Labour’s candidate is a certain Ellie Byrne – a young woman in her early twenties who until recently we’d never heard of.

She keeps a fairly low profile on social media and there’s not much online to suggest she’s previously made a mark as an activist. Yet here she is standing for political office in one of the poorest wards in the country. And being Labour’s candidate in a one-horse, red-rose town, she’s almost certain to win. Which begs the question, who is she? And how did she win the nomination to represent Labour?

Let’s be honest about what caught our attention here. It’s that surname – Byrne. Sounds familiar. And it should because it’s also name of the previous incumbent, Ian Byrne, who announced his resignation at a feisty town hall meeting in January, which triggered this by-election. Ian Byrne is of note for two reasons. Firstly, because he is Ian ‘Two Jobs’ Byrne - the Everton councillor who also became the MP for Liverpool West Derby at the 2019 general election and who broke electoral convention and the rules of good sense by refusing to step down for over two years from his council position. He obviously felt the citizens of Everton and the citizens of West Derby needed him that badly that he had to represent them both. Lucky them.

The other reason why Ian Byrne is of note is because he is Ellie Byrne’s dad, although you wouldn’t know it by looking at any of Labour’s campaign materials. They and the Liverpool Echo which reported her selection are steering well clear of revealing the truth of their relationship as confirmed by residents who have been paid a visit by the Labour team. So what we have here, for clarity is the prospect of a father handing over the baton of office in his electoral ward to his young daughter, as if it was some kind of private enterprise. Now to be fair, there is going to be an election which has to be won, and Liverpool, it must be said, has a long history of keeping it in the family and I’m not talking about the propensity of Andersons (not related). A quick flick through the history books reveals a host of siblings, fathers, husbands, wives, sons and daughters, cousins and aunts who have been regular suckers of the proverbial town hall teat. Peter Kilfoyle’s book, ‘Left Behind’ is very good on this topic.

What do we know about her? From her Facebook profile we know she’s partial to Cadbury’s Cream Eggs, Hannah Montana, and Keeping Up with the Kardashians and for some reason likes Justin Bieber High School.

But still, does it pass the smell test? Given everything that we’ve recently learned about mismanagement and suspected corruption, after the police investigations and arrests, and Labour’s own Hanson Report into what it found to be a ‘toxic culture’ within the Liverpool Labour Group, wouldn’t you bend over backwards to avoid even giving the slightest impression of impropriety or self-serving? Wouldn’t a genuine sense of civic duty demand it?

Still, this could all be cleared up really easily. An interview with the candidate herself would be the chance for her to make her case and show what she’s made of. To show that she’s got here under her own steam. Because maybe she has. But sadly, the Labour Party are not letting her off the leash. No interviews allowed. Such a stance doesn’t breed confidence.

Liverpolitan spoke to Sheila Murphy, who was appointed by Labour’s National Executive Committee (NEC) to oversee the clean-up of the Liverpool Labour group. She was not having it.

“You’re not the only person wanting to speak to Ellie and there’s a bit of a story developing which I think is unfair. Ellie has been a member of the Labour Party for some time and is active in her community. She was selected by Everton members as part of a rigorous process based on her own ability but there won’t be any interviews.”

Sheila was keen to get across the message that Ellie was one of two young candidates (the other standing in Warbreck) and that if the Labour Party was to reinvigorate itself “these are just the kind of people we need to represent us.”

It’s certainly true that Ellie’s candidacy was supported by the official Labour Party apparatus. Following the Caller report, it was announced that candidate lists would be approved by the NEC at least until 2026. Everton ward members made their selection from a short-list that included Brian Dowling and Jean Barrett, both long-time party activists. Speaking to The Post, neither losing candidate had any complaints and positively glowed in their assessments of Ellie.

But doubts still remain. What do we really know about her? She grew up locally, attending Our Lady Immaculate and Notre Dame schools. She claims to have worked in the L6 Community Centre at some point possibly assisting with her father’s foodbank campaigns such as Right to Food. Her spartan Linkedin profile says she graduated from Liverpool University in 2021 with a degree in Law and History. From her social media profile on Facebook we know she’s partial to Cadbury’s Cream Eggs, Hannah Montana, and Keeping Up with the Kardashians and for some reason likes Justin Bieber High School. We also know that she was once pictured standing next to her ever-present dad and Jeremy Corbyn and that she seems to like posting shots of her pouting to the camera although she doesn’t post much at all and she’s hard to find on Twitter, Instagram and Tik Tok. What doesn’t shine out in any of the publicly available information is any kind of political heritage at all. Unless you include liking the Happy Pets app.

None of which is definitely a deal-breaker. Social media is an unreliable tool at the best of times although it’s all we’ve got if she won’t talk to us. But if there’s more to her and she wants your vote, I think she owes it to the electorate to come into the sunlight and tell us what she really thinks in her own words. What she stands for, and what she believes. A campaign leaflet produced by the party machine won’t cut it. If nothing else she should do it to prove that she isn’t just her father’s mouthpiece. That she’s got a mind of her own and the ability to make a difference. Otherwise, the faithful are just being taken for a ride. Again.

Liverpolitan spoke to some of the other parties and candidates contesting the seat. Kevin Robinson-Hale of the Green Party was previously a Chair of Labour’s Everton branch before quitting in 2019, a man well-versed in the ways of the dominant party around here. Yet he seemed a bit reticent to open up, “I haven’t got an opinion on Ian and I don’t know Ellie”, he said. He just felt that Everton voters “shouldn’t get a candidate they’ve never heard of” and residents shouldn’t be forced to “go out of their way to try and get things done.” He was at pains to say that unlike others he wouldn’t be looking to use the council seat as a stepping stone to parliament.

We also heard from Local Lib Dem Leader, Richard Kemp, who was quick to shoot down any suggestions of nepotism. “Having relatives as a fellow councillor is not unusual,” he told us. “My wife served alongside me for 23 years.” Indeed. But then he performed an about-face, thundering into his keyboard “Labour now seems to favour the inherited system of power and patronage in Liverpool! What next? Baron Byrne of West Derby!?” Richard seemed particularly exercised that Ian Byrne had timed his resignation “to allow his daughter to reach 18”, a curious piece of factual inaccuracy given that as we pointed out earlier, Ellie is actually a university graduate going on 23 years old. That snippet I suspect was picked up from a recent email to Liverpool Council and the Government Commissioners into which he was cc’d from a ‘Ms Bett and Residents’ who are extremely exercised by the selection of Ellie as Labour’s candidate. Although, he may have picked it up from a separate anonymous email from ‘Labour Activists in Everton Ward’ who are equally infuriated.

“Does Labour condone nepotism as a way to recruit councillor candidates?” they wrote. “To say we are startled by this information that the Candidate for this by-election is actually the daughter of the outgoing councillor is an understatement and we hope the National Labour Party if not the local Everton CLP rectify this situation before the election date to avoid a national scandal.”

Clearly, beneath the surface all is not calm in Everton ward and despite the efforts of Labour Party fixers, there appears to be considerable disquiet at Ellie’s selection at least amongst some of the group’s natural supporters. Right now, we’re left to wonder, what is it that makes Miss Byrne the perfect candidate to represent the interests of a ward which struggles with the basics of food and employment? Until, she speaks up we’ll never know. I guess the voters of Everton will just have to make up their own minds. But if the continual re-election of Malcolm ‘Milk'em’ Kennedy by neighbouring Kirkdale - who chose to live in Spain rather than in Liverpool - is anything to go by ... it looks like there will be few obstacles to Ellie Byrne enjoying a glittering political career, whether she’s up to the job or not. He may well have reluctantly stepped aside (three years after he perhaps should have done) but you can bet Ellie will be doing her best to keep the red flag flying, under the watchful guidance of Dad, Ian.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach.

Share the article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

No Platforming: Taking statues off their pedestals

Statues have been on the front line of the culture wars ever since protesters dragged the bronze figure of ex-slaver and merchant, Edward Colston into Bristol Harbour. Today, the fate of many other controversial statues still hangs in the balance. But while some argue for their removal and others try to re-contextualise them in brightly coloured outfits often designed to mock, Art Historian, Ed Williams argues there’s a third way of dealing with them - bring the statues down to our level.

Ed Williams

An unforeseen consequence of the enforced closure of our cultural institutions during the recent ‘lockdowns’ is that the curious and bored alike encountered, perhaps for the first time, the numerous statutes and public monuments located in our major towns and cities. Much like an open air exhibition, these free ‘exhibits’ were one of the few cultural experiences available during the uncertain and tedious days of enforced ennui.

Liverpool, like many cities of a similar ‘vintage’, has a plethora of statues. They are a testament to the city’s ‘fathers’ and an attempt to engender a sense of civic pride, commemorating as they do the legacy of the ‘big men’, the ‘great and the good’. These honoraries were predominately white, bourgeoisie males who (allegedly) conformed to the idealised values of piety, philanthropy, the championing of free trade or military prowess in some overseas campaign.

Though for many such art works elicit nothing more than indifference as they hurry past in the rain, for others contemporary reaction has become deeply politicised, ranging from visceral contempt to staunch defence. Most graphically, the toppling in Bristol of the statue of slave trading merchant Edward Colston and the perceived threat posed to others draws attention to the fiercely contested debate between those who seek their removal and those who feel that such change represents an existential challenge to ‘tradition’ and ‘history’, a reductive dispute that places figurative sculpture very much on the battle front in the ongoing ‘culture wars’. In light of such a polarised debate perhaps there is an alternative approach to removal or maintaining the status quo, one which seeks to re-imagine the role of public figurative sculpture altogether. Fundamental to this approach is to question why do sculptures exist? What, if any, function do they serve and can these aims be achieved via alternative means?

Different approaches to the statue problem. Some take direct inspiration from events in Bristol…

The vogue for erecting sculptures of the ‘worthy’ emerged in Britain during the late eighteenth century, a period in which the nascent British Empire sought to emulate, through wholesale adoption, the tastes and virtues of the great classical civilizations of Greece and Rome.

This fascination with statues reached its peak in the Victorian era when it approached something akin to mania. Liverpool, like the majority of towns and cities in the North of England had experienced relatively recent urbanisation. Unlike those great ecclesiastical centres of York, Chester, Hexham or Durham, most of the ‘boom’ towns of the Industrial Revolution lacked the convivial Roman ruins, medieval fortifications, or ancient sites of worship that conveyed a sense of historic importance, so a new civic story was required for these modern metropolises. Sculpture allowed a sense of ‘history’ to be created instantly. Committing a likeness to bronze, or more commonly embalming in marble those local or national heroes provided more than just a mnemonic memory device for the masses (something which the recently developed art of photography was mastering with ever greater verisimilitude). The statue was first and foremost a didactic tool for conveying officially sanctioned moral education. ‘Here before you stands’, his (rarely her) virtues and triumphs, dates and places listed instructively. This way, civic history, like classical history can be taught by rote through stone to future generations of proud civic citizens.

The toppling in Bristol of the statue of Edward Colston and the perceived threat posed to others places figurative sculpture very much on the battle front in the ongoing ‘culture wars’.

These moral lessons were further, powerfully enhanced by the sighting of works on plinths. The public were compelled to literally ‘look up’ to these individuals, lending them an almost god-like aura, respectful awe implicit in the architecture. Conversely they (the statues) cast a downward glance upon us, lesser mortals, few, if any of whom, would be deemed worthy of such sculptural dedication. This asymmetric relationship is perhaps the most contentious issue, in this author’s opinion. Why should we be compelled to look up? Craning one’s neck skyward is not the ideal way to view any artwork, especially when dealing with the additional height of those old regal and military favourites, the mounted equestrian statues. Frankly from this vantage point you might conclude that one stylized representation of a Victorian is much the same as the other (and oddly never too dissimilar to the late Prince Albert). Whilst the curious amongst us may trouble ourselves to read the plinth plaque (though many are so weather worn as to be illegible) their elevated position compromises comprehension. We simply cannot appreciate, nor begin to truly understand and scrutinize, the work from this position.

Stranger still perhaps is the location of such works, often arranged together in neat, parallel rows or clustered together as in Liverpool’s St John’s Gardens. Was this an attempt to create an open air pantheon of sorts? Yet as time passes, and we become ever more distant to the reasons why these people were heralded in the first place, the result often feels more like a dusty necropolis, a graveyard of dead luminaries, littering the city, lest the tourists be interested.

If such works now appear to be instructive failures could their continued presence perhaps reveal something more contentious? Are they not now reminders of a ‘once great past’, a symptom of the wider British malaise, the fetishization of previous times, those fabled ‘good old days’? This fatuous narrative remains a potent deceit, which serves to stymie progress, especially in a city like Liverpool where heritage is pinned as our number one asset. If things were indeed better ‘back then’, we truly are doomed. In light of the supposed ‘culture wars’ a wider debate is needed to determine the proper place of the past in our national dialogue, and one starting point may be statues and their continued legacy.

This author’s, perhaps provocative suggestion is not to remove these works, nor to ‘re-purpose’ them in the latest postmodern fashion by ‘dressing them up’ in colourful clothes, as was seen during the recent Sky Arts ‘Statues Redressed’ programme, but rather to remove them from their plinths and site them at ground level. This way we can encounter these figures more closely as physical equals and as fallible humans, not superior secular gods.

Such an approach is not unprecedented. More recent commissions such as the statues of Sir John and Cecil Moores in Church Street, The ‘Fab Four’ at The Pier Head and those of Sir Ken Dodd and Bessie Braddock at Lime Street Station are all sited at pavement level. Being devoid of plinths it allows us to interrogate their features and to consider them further as real people, rather than simply ‘grandees’. In short, we encounter and experience the statues as figurative artworks, not pieces of sociological propaganda. Divested of their lofty position, we can begin the process of critique from a more nuanced position. After all, the measure of history’s heroes and villains is rarely clear cut. Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the ‘Greatest Briton’ according to a BBC poll, was also an incompetent military adventurer (Gallipoli) and violent strike breaker (Gun Boats on the Mersey), who allowed millions to starve in Bengal during the Second World War. The truth is, simple judgements are not always easily arrived at. Life is complex. Besides, if you look at our most popular media tastes today, we tend now to prefer the flawed anti-hero, or loveable rogue over the unsullied but rather boring saints of yesteryear. Heath Ledger’s Joker was a far more compelling character than Christian Bale’s growling Batman. Such dubious figures may be perceived as models for redemption for those of an optimistic streak, or perhaps they remind us that we are all deeply fallible, despite our best efforts. In seeking to bring statues ‘down to our level’, we are effectively humanising them in order to better understand them. That doesn’t mean that we necessarily forgive them their sins, just that we are in a better position to take a view.

Clockwise starting top left: Stone relief of 2 slave children (St Martins Bank), a petition for its removal attracted approx 2000 signatures; Penny Lane street signs were defaced despite no proven link to slavery; Chained prisoners of war beneath a victorious Admiral Nelson (Exchange Flags), the figures are often mistaken for African slaves; Explorer Christopher Columbus dressed in an African-inspired Elizabethan ruff (Sefton Park Palm House) as part of the Sky Arts project, Statues Redressed. Images courtesy of Jane Anderson

Notwithstanding Lenin’s allegedly prophetic assertion that statues are for pigeons to shit on, commissioning figurative sculptures remains as popular as ever. Is this evidence of their continued cultural significance, or yet another example of a paucity of imagination when faced with the tyranny of ‘tradition’? Is their use so hard wired into our cultural psyche that we have no other alternative but to default to the obligatory statue as the go-to reminders of our latter day worthies? Who knows but at least today the metal and stone pantheon has been somewhat democratized with footballers, comedians, actors and musicians just as likely to get the nod (sometimes with dubious results). This is most probably a good thing as welcome evidence of a more meritocratic society which appreciates and applauds those whose lives and work resonate more with ‘ordinary’ people. A cynical alternative may be that we just set the bar on achievement too low or are just a bit too quick to judge greatness?