Recent features

Taylor Town Kitsch, Ersatz Culture and the Art of Forgetting

As Liverpool rolled out the red carpet for Taylor Swift, America's biggest pop star and her hordes of cowboy hat-clad 'Swifties' , the city's culture chiefs congratulated themselves on the global media coverage. 'This is who we are' seemed the message. But in this time of forgetting, John Egan wonders, is kitsch really who we are and what we want to be?

“If we don't know where we are, we don't know who we are,”

Jon Egan

It may seem perverse to even pose this question, especially as Liverpool was only recently judged by Which? as the UK's best large city for a short break by virtue of its “fantastic cultural scene”. But ask it I must. Despite once proudly wearing the title of European Capital of Culture of 2008, is Liverpool really a cultural city? To paraphrase the BBC's celebrated Brains Trust stalwart, C.M Joad, I suppose it all depends on what you mean by culture?

My worry is that Liverpool appears to be operating under an increasingly narrow and debilitating definition of culture, or at least, offering to the world a version of its cultural self that seems weirdly stunted, shallow and ultimately synthetic - something the American art critic and essayist, Clement Greenberg might have characterised as ‘kitsch’. Writing in 1939, Greenberg's essay 'The Avant-Garde and Kitsch' defined the latter as embracing popular commercial culture including Hollywood movies, pulp fiction and Tin Pan Alley music. He saw kitsch as a product of rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, which created a new market for “ersatz culture destined for those who, insensible to the values of genuine culture, are hungry nevertheless for the diversion that only culture of some sort can provide.” These mass-produced consumer artifacts, by definition formulaic and for-profit, had driven out "folk art" and authentic popular culture replacing it with what were essentially commodities.

One does not have to be a Marxist (Greenberg was) or a cultural snob (he was possibly one of those as well) to be slightly worried that Liverpool's cultural brand is beginning to lean too heavily in the direction of the kitsch and the hyper-commercial. It was a concern, first articulated in the run-up to Liverpool's hosting of Eurovision last year by the Daily Telegraph’s Chris Moss, “Liverpool has chosen Eurovision kitsch over protecting its history and heritage”, and explored further in my Liverpolitan article, “Liverpool's Imperfect Pitch”. A feeling that has only been exacerbated by the recent Taylor Town phenomenon.

For the somehow blissfully unaware, Taylor Town was a “fun-filled” council-funded initiative to transform the city of Liverpool into a Taylor Swift “playground” designed to offer a “proper scouse welcome” to the American pop star and her legion of fans before three sell-out shows at the Anfield stadium. This included commissioning eleven art installations each symbolising one of the artist’s 11 albums – everything from a moss-covered grand piano to a snake and skull-clad golden throne – all designed to be instantly instagrammable.

A golden throne inspired by Swift's 'Reputation' era forms part of Liverpool's Taylor Town trail conveniently located for lunch options. Image: Visit Liverpool.

Sure, Liverpool wasn't the only port of call on Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour to dress-up for the Swifties, but wasn't there something about the hype and hullabaloo that went beyond due recognition and celebration of a major musical event?

My queasiness about Liverpool's Taylor Town re-brand is more than mere snobbishness, or a patronising disdain for popular culture. Our willingness to conflate the city’s very identity with the persona of the American pop icon carries worrying echoes of Councillor Harry Doyle's “perfect fit” mantra between Liverpool and Eurovision. This is somehow more than just a smart bit of opportunistic marketing; it implies some deeper and integral affinity. Public pronouncements by Doyle and Claire McColgan, invoking the spirit of Eurovision, suggested Swift's visitation was seen as an epiphanic moment of self-realisation. In a spirit of almost quasi-mystical reverie, Clare McColgan explained; “the world can be a very dark place and in Liverpool, it’s light.”

If Taylor Swift has somehow become the embodiment of our cultural identity and ambition, what exactly have we become? The American cultural writer and scholar, Louis Menand observed, “in the 1950s the United States exported a mass market commercial product to Europe [rock n roll]. In the 1960s, it got back a hip and smart popular art form.” He is, of course referencing The Beatles and sadly it seems that we are once again being sold short on this cultural transaction.

“Liverpool's cultural brand is beginning to lean too heavily in the direction of the kitsch and the hyper-commercial.”

Despite Doyle's claim that her arrival “was very much in the spirit of the city's musical history”, Taylor Swift is not The Beatles. In the words of the Canadian feminist writer and blogger, Meghan Murphy she “will be forgotten in 20 years, which cannot be said for Janis Joplin, Carly Simon, Etta James, Leslie Gore, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Whitney Houston, Aretha Franklin, or Tina Turner... And none of those women made it on account of being beautiful or having a string of celebrity boyfriends. Certainly, they will not be remembered for their ability to command the hysterical attention of legions of young fans. They were just very good.”

Swift may be a global superstar, a role model and a performer with genuinely admirable philanthropic and compassionate sensibilities, but she is also according to Murphy, bland, manufactured and ephemeral - the literal embodiment of kitsch. Merely staging one of her concerts does not boost our cultural capital or say anything true or meaningful about who we are. For Harry Doyle, the sheer scale of global media coverage is its own justification. “So far, our city has been featured on just about every media outlet worldwide, including the Today Show in the US”, he excitedly claimed, as if a simple volumetric calculation was enough to establish cultural prestige.

Making “the city part of the show” to quote Claire McColgan, and building a civic and cultural brand by staging big events, was the thesis underpinning the city's post-Capital of Culture prospectus, The Liverpool Plan. Describing Liverpool itself as “The Great Stage” it prefigured a reality that those concerned about the condition and accessibility of our waterfront and parks are beginning to realise has troubling consequences. There may well be a perfectly credible argument for hosting large scale events and showcasing the city's architectural and heritage assets, but this is no substitute for what cities, once saw as their responsibility to promote and nurture culture in its widest sense.

So, do we need a different yardstick for what makes a cultural city? If Liverpool wasn't a cultural city, or had not been a cultural city, then I would in all probability not be here. When my father accepted a job in Liverpool it was intended as a stepping-stone to Dublin, the city where my parents had met and always aspired to settle down. It was the discovery that Liverpool possessed everything that Dublin promised, that persuaded them to put down roots in a place that satisfied all their cultural appetites. This was a time when both UK and international opera and ballet companies regularly visited our city, when cutting-edge theatrical productions had their pre-West End runs in the city's array of thriving theatres. It was also the time when Sam Wanamaker was transforming the late lamented New Shakespeare Theatre into what The Guardian described as “one of the first multi-strand art centres in Europe” - a venue that was open 12 hours a day, staged contemporary theatre as well as films, lectures, jazz concerts and art exhibitions and put on “free shows for workers every Wednesday afternoon.”

“Taylor Swift may be a global superstar with admirable philanthropic sensibilities, but she is also bland, manufactured and ephemeral - the literal embodiment of kitsch.”

Moss-covered piano inspired by Swift's 'Folklore' era, one of eleven exhibits that made up the Liverpool Taylor Town trail. Image: Visit Liverpool

From the 19th century onwards, culture was embedded in Liverpool's civic project, the city’s self-image being proudly cosmopolitan rather than prosaically provincial. “High Art” might not be the exclusive criterion for what constitutes a cultural city, but it was, for a time at least, integral to Liverpool’s claim to that status. Now it would appear that culture has no intrinsic value other than as a means to an end. Taylor Town was, in Doyle's words, “much needed PR the city needs to attract investment and visitors.”

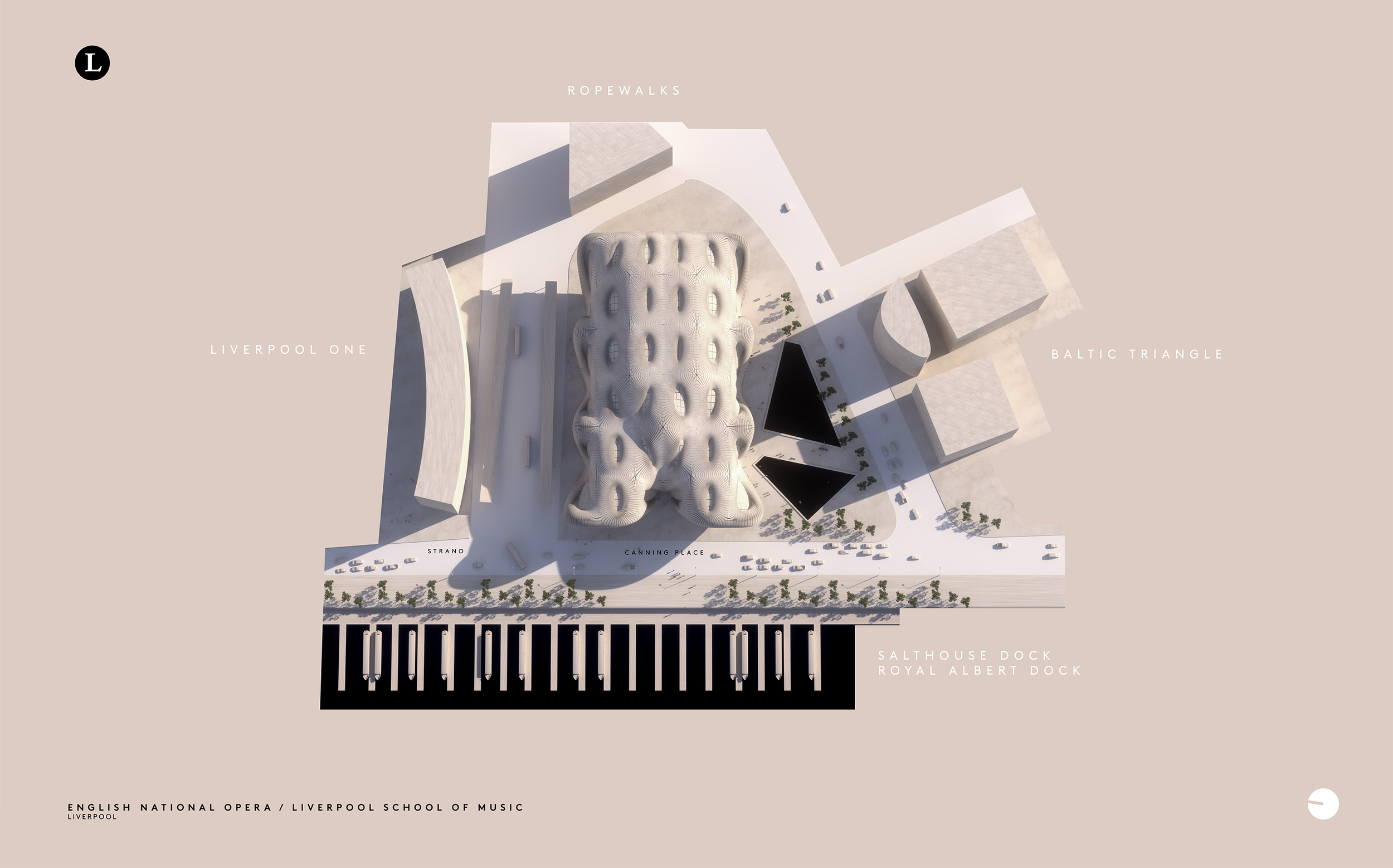

The irony is that a positioning or investment strategy focused on big events and blitz publicity is quite probably a less effective strategy than one focused on stimulating cultural quality and diversity of offer. Events may deliver a short-term boost to the tourism and hospitality sector, but smart cities understand that the depth, quality and originality of their cultural offer is what draws investment and attracts and retains people. Once again, it might be instructive to look to our regional neighbour, Manchester for inspiration. The Manchester International Festival (MIF) not only reveals a city that, unlike the organisers of LIMF (Liverpool International Music Festival), understands the meaning of the word "international," but is also a masterclass in intelligent place marketing. MIFs inspired, left-field commissions and collaborations are deftly configured to spell out one simple message - “Hey, we're just like London.” In other words, we're the sort of city that's ready-made for banished BBC executives, relocating corporates, boho entrepreneurs or the English National Opera (ENO). Manchester benchmarks its cultural strategy against cities like Barcelona and Montreal, disruptor second cities harbouring global ambitions.

There was a sad inevitability about the ENO relocation to Manchester after Liverpool had failed to make it beyond the shortlist. Liverpool's city leaders offered a flimsy defence of their laissez-faire approach to pitching - that this was a process-driven exercise where lobbying and advocacy were superfluous and potentially counterproductive. Yet as a well-placed Manchester source explained, “Yes, it was process-driven, but the timing worked for us, coming [so soon] after the Chanel Show which secured exactly the right kind of media coverage.” (Note - quality not quantity) “But the key was the availability of a versatile and conveniently available performance venue designed by Rem Koolhaas, that didn't really have a defined function or use-strategy.” The commissioning of The Factory / Aviva Studios was an audacious exercise in the ‘build it and they will come’ approach to urban regeneration, and proof that Manchester, like the Biblical wise virgins, is a city always primed with a trimmed wick and plentiful supply of oil.

Probably, a more significant consideration was the perception that Manchester had an audience for opera whilst Liverpool possibly did not. One of the most depressing episodes in my professional life came during a discussion with Liverpool's big cultural players whilst working on ResPublica's HS2 for Liverpool advocacy project. A prominent, though now departed, head of a prestigious cultural institution, lamented that they would love to deliver a more ambitious programme (as they had in 2008) if only they could “attract an audience from Manchester.” Yet as the success of Ralph Fiennes' Macbeth production at the Depot venue proved last year, this comment is as ill-informed as it is profoundly dispiriting.

“From the two fake Caverns and tat memorabilia of Matthew Street to the anodyne mediocrity of “The Beatles Story”, we are now celebrating what was once subversive popular art in the guise of the mass-produced ersatz culture to which it was once the antidote.”

The Beatles Story: A fake grave cast in authentic-looking granite to a fictitious character Paul McCartney claims he ‘made up’. Could this be any more ersatz or is it just ‘meta’?

Photo: Paul Bryan

For all its sophistication and legacy of transformed cultural assets, there is still a whiff of utilitarianism about Manchester's approach, and a view of culture as primarily an instrument of economic regeneration. Hence an emerging new strategy with a greater emphasis on what they term “cultural democracy” with a more equal and diverse distribution of cultural resources and opportunities.

Notwithstanding the undoubted quality of our visual arts assets and collections, Liverpool's performing arts offer is now sadly diminished and, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra excepted, is hardly commensurate with what you’d expect of an aspiring cultural city. If Liverpool is to entertain genuine claims to that title, then maybe we need another definition that isn't founded merely on physical assets or an eye-catching events programme?

For American essayist and poet, Wendell Berry “culture is what happens, when the same people, live in the same place for a long time.” For Berry “same people” doesn't entail ethnic homogeneity. His own Appalachian culture is a heady brew of English, Scots Irish, Cherokee and African influences that even a fledgling Taylor Swift, once wanted to get a piece of. His definition is closer to what Clement Greenberg saw as the antidote to kitsch - “folk art”. This is culture with roots, with an organic and intimate connection to place, with a character, accent and disposition that are distinctive and inimitable. By this yardstick, cultural cities are not just places that stage culture or boast a wealth of cultural assets, they also cultivate and disseminate it. It is in this sense that Liverpool can perhaps advance its most convincing claim to be a cultural city.

Liverpool's culture is as much an ambience and attitude as it is an archive of expressions and artefacts. It emerges in creative convulsions that emanate from a deep geology, a substratum of shared stories and memories. In the 1960s, it was Merseybeat, the poetry of McGough, Patten and Henri, the forgotten genius of sculptor, Arthur Dooley, and the phantasmagorical humour of Ken Dodd. (Are the jam butty mines of Knotty Ash just charming whimsy or, like Williamson's Tunnels, secret portals into the arcane depths of Liverpool's collective unconscious?). The early noughties, as the city began to dream of becoming a European Capital of Culture, happily coincided with another creative spasm, as Fiona Banner was shortlisted for the Turner Prize, Paul Farley won the Whitbread Poetry Prize, Delta Sonic Records were trailblazing Liverpool's third musical wave, and Alex Cox was back in town collaborating with Frank Cottrell Boyce on their, as yet unrecognised masterpiece, Revenger's Tragedy.

“Memory is the alchemy that transmutes the base metal of the everyday into the life-enhancing elixir of an authentic culture. But we live in a time of forgetting, of uprootedness, fracture and disinheritance, and even a city famed, and often derided, for its obsessive nostalgia, is not immune from this pervasive fixation with the immediate, the superficial and the kitsch.”

It's not just the social realist triumvirate of Bleasdale, Russell and McGovern whose writings are moored in the anchorage of their home port city. For novelists like Beryl Bainbridge, Nicholas Monsarrat and Malcolm Lowry, Liverpool looms and lurks in the shadows of their fiction even as a point of departure or an unspoken absence. For two contemporary Liverpool writers, the city is an object of almost erotic communion. Musician Paul Simpson's gorgeously poetic memoir, Revolutionary Spirit, and Jeff Young's Ghost Town are immersions in secret treasuries of memory and miracle. Young is Liverpool's cartographer of the marvellous, tour guide to our fevered Dreamtime for whom Liverpool “is the haunted place of remembering.”

Memory is the alchemy that binds past and present, that invisibly entwines the living with the dead. It's what transmutes the base metal of the everyday into the life-enhancing elixir of an authentic culture. But we live in a time of forgetting, of uprootedness, fracture and disinheritance, and even a city famed, and often derided, for its obsessive nostalgia, is not immune from this pervasive fixation with the immediate, the superficial and the kitsch. In a blisteringly brilliant essay in The Post, Laurence Thompson poses the question, why is Liverpool unwilling or unable to recognise the creative achievement of filmmaker and “great visual poet of remembrance,” Terence Davies, and his seminal trilogy Distant Voices, Still Lives?

“That such an impressive work of art came both from and was about Liverpool seems worthy of commemoration. Yet it’s impossible to imagine the Royal Court commissioning a major contemporary playwright to adapt a stage revival of Distant Voices, Still Lives... I’m not advocating Davies’s memory falling into the hands of the usual custodians of Liverpool’s heritage. What’s the point in putting up a blue plaque commemorating the original Eric’s when the current Eric’s is so unbelievably shite? But the choice between amnesia and kitsch must be a false dichotomy.”

The French seem more inclined to remember the seminal films of Terence Davies, than Liverpool, the city of his own birth. A retrospective held at the Paris Pompidou Centre in March 2024.

Alas, it seems we are increasingly opting for kitsch, not just in terms of our desire to bask in the reflected aura of Eurovision and Taylor Swift, but also in how we package and commodify our own cultural legacy. From the two fake Caverns and tat memorabilia of Matthew Street to the anodyne mediocrity of “The Beatles Story”, we are now celebrating what was once subversive popular art in the guise of the mass-produced ersatz culture to which it was once the antidote. Kitsch's suffocating omnipresence is a soporific that dulls memory and transports us into its own featureless geography. “If we don't know where we are, we don't know who we are,” explains Wendell Berry. For Berry, culture, identity and place are a sacred trinity without which human society withers and sinks into the shallow abyss that G.K. Chesterton termed the “flat wilderness of standardisation.” A time of forgetting is also a time of false belonging. Polarised politics, bitter culture wars and horrifying street violence are in different ways a thrashing around in search of connections to something enduring and meaningful in the bewildering Babel of post-modernity.

Consigning an artist of Terence Davies' stature to the margins of oblivion is sinful enough, but it is emblematic of a deeper estrangement and disconnection. A city that squanders its World Heritage Status, that's indifferent to its own cultural history and cheerfully embraces an architectural aesthetic of shabby and soulless mediocrity, is forsaking its very identity. In the spirit of Louis Aragon's Le Paysan de Paris, Jeff Young chronicles Liverpool’s neglectful disregard for the overlooked, the curious and the idiosyncratic, for the magnetically charged spaces and landmarks, like the sadly demolished Futurist cinema, that are the coordinates of our collective remembering. Ghost Town is an odyssey in search of a submerged city, drowning under the dead weight of the bland and the banal.

“The magic is leaching from the city, the shadows and alleyways are emptying, and so we walk through wastelands where the magic used to be, we gather autumn leaves from gutters and dirt from the rubble of demolished sacred places.”

Identity and culture are rooted in the original, the distinctive and the unwonted, in things that should be reverenced, not wilfully expended.

At the conclusion of his Gerard Manley Hopkins Lecture at Hope University earlier this year, I asked Jeff, how do we breach the chasm that seems to separate those who love the city, from those who govern it? There isn't a simple answer, but it must surely involve some thoughtful consideration of what it means to be a cultural city. Culture in its authentic form, is salvific. Being connected to a place, its story and to each other is to fulfil one of our most basic human yearnings.

For now, at least, the circus has left town. Eurovision and Taylor Swift have moved on to the next “destination.” But if we want to get in touch with our culture, we need to see through the eyes of poets and artists like Jeff Young and Terence Davies, to look beyond the empty stage for something part-buried and only half remembered - the immeasurable richness of a cultural city.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Main Image: Paul Bryan

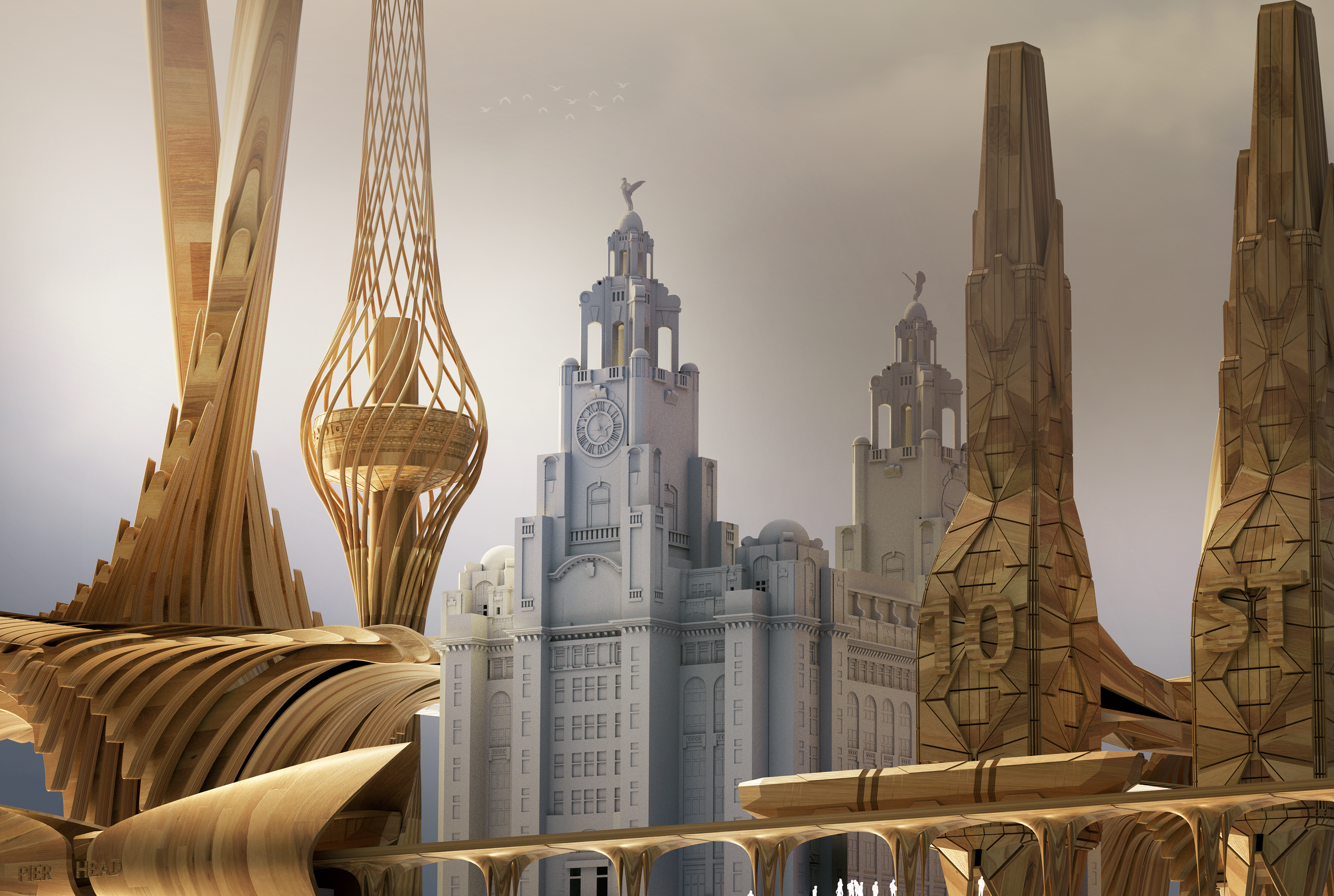

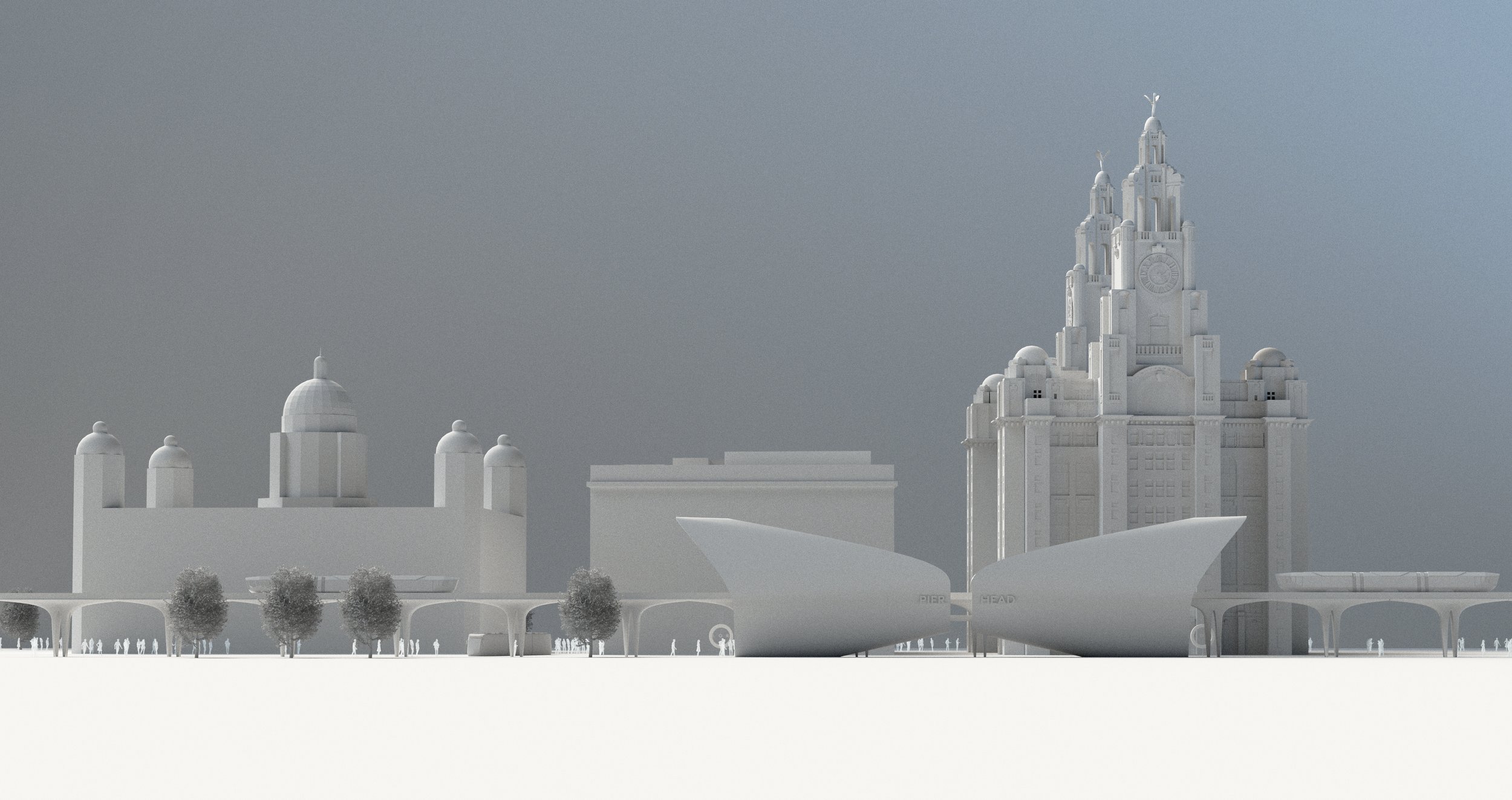

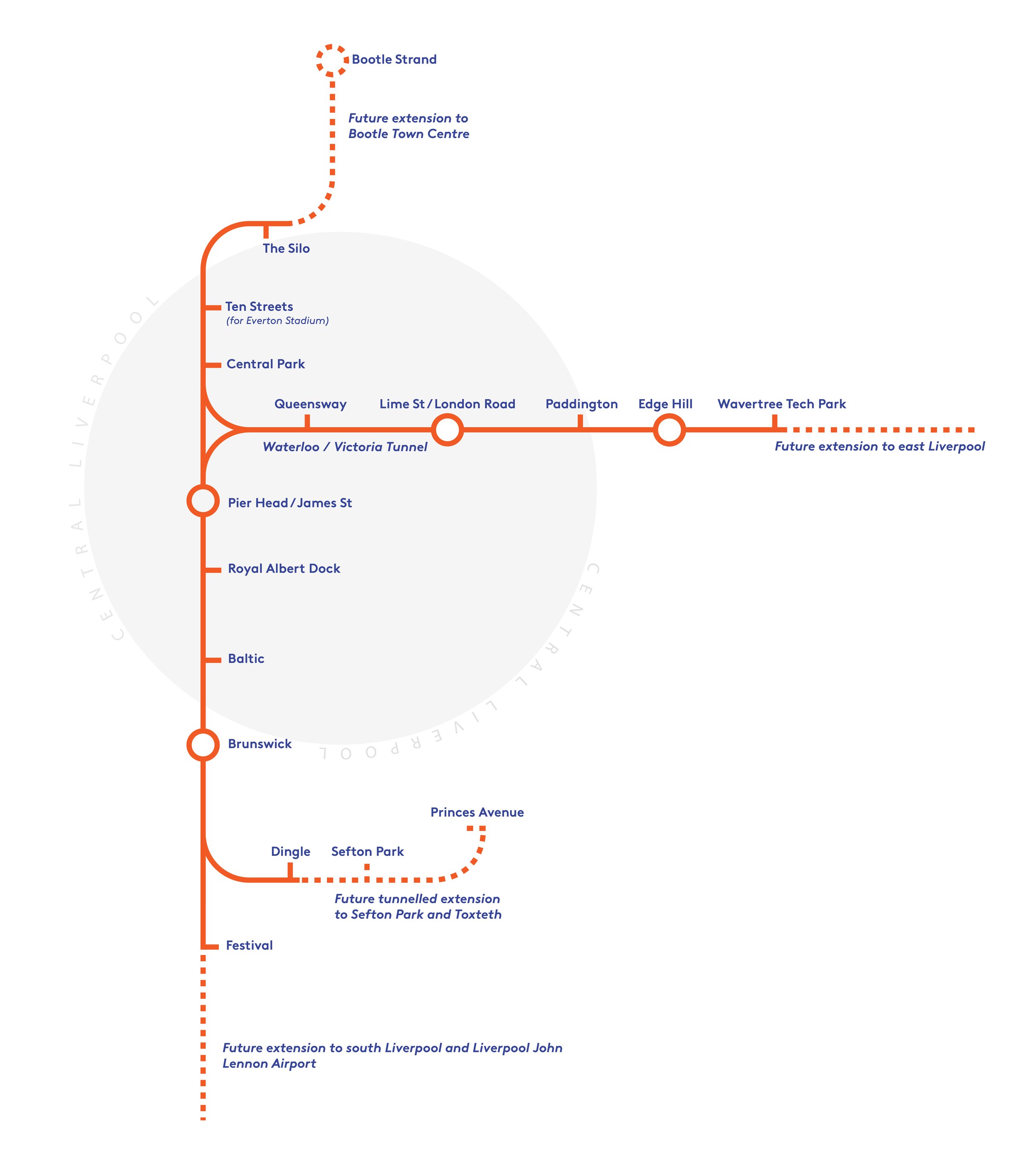

What next for the Wirral Waterfront?

As a child I found Wirral, and Birkenhead in particular, to be a deeply mystifying place. I knew that Ireland, where we went on holiday, was across the water, but where exactly was this other place? It wasn’t Liverpool, but was it even England or maybe Wales, or some strange liminal place existing outside my primitive geographical understanding?

Jon Egan

As a child I found Wirral, and Birkenhead in particular, to be a deeply mystifying place. I knew that Ireland, where we went on holiday, was across the water, but where exactly was this other place? It wasn’t Liverpool, but was it even England or maybe Wales, or some strange liminal place existing outside my primitive geographical understanding?

My earliest journeys across the Mersey did little to dispel Wirral's sense of disquieting otherness. The deep, dark descent into the underworld of the Mersey Tunnel only reinforced its obvious detachment from humdrum reality. This must be the other side of the looking glass.

Years later during my counter-cultural phase, and in the spirit of Parisian Surrealist explorations, we’d take “the metro” to Birkenhead in search of the merveilleux. Birkenhead’s numinous aura was only magnified by the eerie absence of people, the monumental grandeur of Hamilton Square echoing the ominous emptiness and abandonment of Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical city scapes.

In later years my associations with Birkenhead became more prosaic and practical through involvement in a succession of aborted regeneration initiatives and "visionary" but unrealised masterplans. Spending days talking to frustrated residents and world-weary stakeholders I was struck by their sad fatalism, as if the town had been subject to some strange and enervating enchantment. As Liverpool’s cityscape was magically transformed before their very eyes, Birkenhead seemed frozen in a state of suspended animation akin to Narnia trapped in its perpetual winter.

But of course there was nothing supernatural about the decline of Birkenhead. Once styled the City of The Future, Birkenhead has a proud and pioneering history. In addition to its global shipbuilding prowess, it’s the town that built the UK’s first public park, its first Municipal College of Art as well as Europe’s first tramway. Birkenhead’s curse is a toxic blend of economic decline and disastrous urban planning, making Birkenhead a place that’s easier to pass through than get to. Whilst cars, people and investment pass Birkenhead by, it’s tempting (and partially true) to point the finger at poor leadership and botched planning. But is there another more fundamental reason for the town’s baleful situation? Is it rooted in Birkenhead and Wirral’s deeper crisis of identity?

Regeneration has to be informed and framed by a sense of place - a clarity of purpose and identity. Without an existential paradigm regeneration is likely to be a series of disconnected and arbitrary interventions, very often aiming to undo the unforeseen consequences of a previously failed intervention. Birkenhead shopping centre is a palimpsest of flawed visions and ham-fisted initiatives. It is still just about possible to discern the archaeological remnants of what was, once upon a time, a high street (Grange Road), dissected, butchered and disfigured by ugly and already half-redundant modernist protuberances . This is town planning re-imagined as self-mutilation.

In 2001 Wirral Council attempted to resolve the peninsula's ambiguous identity with a bold, but alas unsuccessful bid for City Status. This was always a difficult proposition to sell given the uneasy relationship between the borough's urban Mersey edge and its bucolic hinterland. If Wirral isn't a city, then what is it? A municipal construct? A geographical descriptor? A lifestyle aspiration? Is it one place or an amalgam of places with quite different characteristics, histories and identities? It is difficult to suppress the suspicion that the failure to arrest the decline of its distinct urban centres has something to do with their slow immersion and disappearance into an amorphous and confused abstraction. It's little wonder that a Council without a settled sense of identity (its fractious communities historically divided about whether they should have an L or a CH postcode), should struggle to formulate or deliver a coherent regeneration vision. To borrow a Marxist analogy, Wirral's debilitating dialectic needed a resolving synthesis - and happily they found one.

‘Downtown Birkenhead needs to re-orientate itself and define its future in relation to an already burgeoning Liverpool City Centre…’

The Wirral Local Plan (currently awaiting Government approval) ingeniously united the borough's disparate communities and political factions with a strategy to vigorously defend its greenbelt and direct all new housing development onto urban and brownfield sites. Implicit in the plan are two revelatory and foundational propositions.

1) Wirral is not a homogenous place - its Mersey edge is a connected urban strip that is qualitatively different from the pastoral commuter settlements west of the M53. (Income disparity between the borough's most deprived and affluent areas is greater than in any other UK local authority area.

2) The history, identity and future of the urban edge is umbilically connected to the place it stirs out at across the Mersey (but sometimes thinks exists in a different hemisphere) - it’s Liverpool’s Left Bank.

Wirral's Left Bank vision was a new regeneration narrative to reposition and re-imagine the Mersey shore, but is also the core strategy against predatory housebuilders’ determination to challenge the no passaran defence of the greenbelt. However, this defence would only be sustainable if Wirral could make the Left Bank a sufficiently attractive and commercially rewarding location for the scale of building necessary to meet the borough's new homes requirement.

And herein lies the challenge. From New Ferry to New Brighton, the Left Bank littoral has, in recent decades - with one gloriously idiosyncratic exception (more later) - been a virtual regeneration exclusion zone. Turning what is often perceived as Liverpool's down at heel urban annexe into a thriving regeneration powerhouse is a challenge requiring exceptional presentational and practical capabilities.

The presentational brief has been curated by an impressive creative team, combining the branding and visualising expertise of designer, Miles Falkingham with the editorial acumen and eloquence of Birkenhead writer, David Lloyd, The Left Bank mood board, flawlessly realised in the eponymous digital and print magazine, presents a richly fertile incipient oasis, pregnant with possibilities and welcoming to innovators, prospectors and the independently inclined.

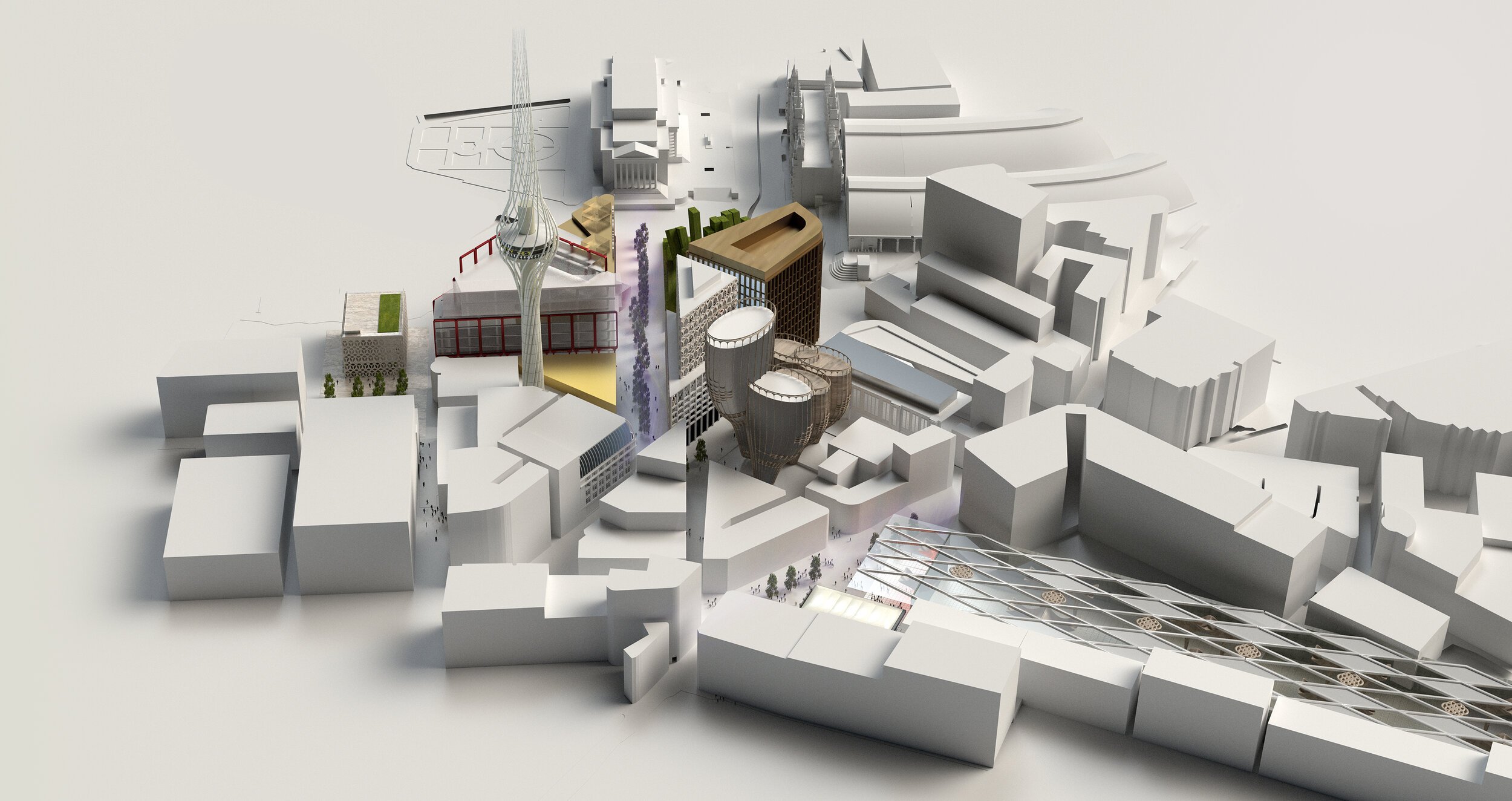

Birkenhead Dock Branch Park, conceptual visualisation.

The Left Bank

As a destination for the discerning, Left Bank is a counterpoint to a Right Bank (Liverpool) whose identity and character is being lost under the stultifying uniformity of the standard regeneration model.

But the Left Bank idea is more than a cleverly crafted re-branding exercise. It is also a set of values and sign posts to inform the delivery of what is potentially Wirral's most transformational regeneration windfall. Birkenhead 2040 outlines a radical vision for a re-imagined Birkenhead town centre underpinned by a series of successful Levelling Up and Town Deal funding awards totalling £80 million.

In 2016, following on from my involvement in a consultation on yet another undelivered regeneration project, I was one of a small group who produced an unsolicited document sent to Wirral's then Regeneration Director, entitled Manifesto for Downtown Birkenhead. A call to arms, it's opening paragraph set out the key challenge and imperative:

"Downtown Birkenhead needs to re-orientate itself and define its future in relation to an already burgeoning Liverpool City Centre. Reaching out and strengthening its sense of proximity and connectedness will be vital in attracting the energy, activity and people that are currently absent from a once vibrant centre."

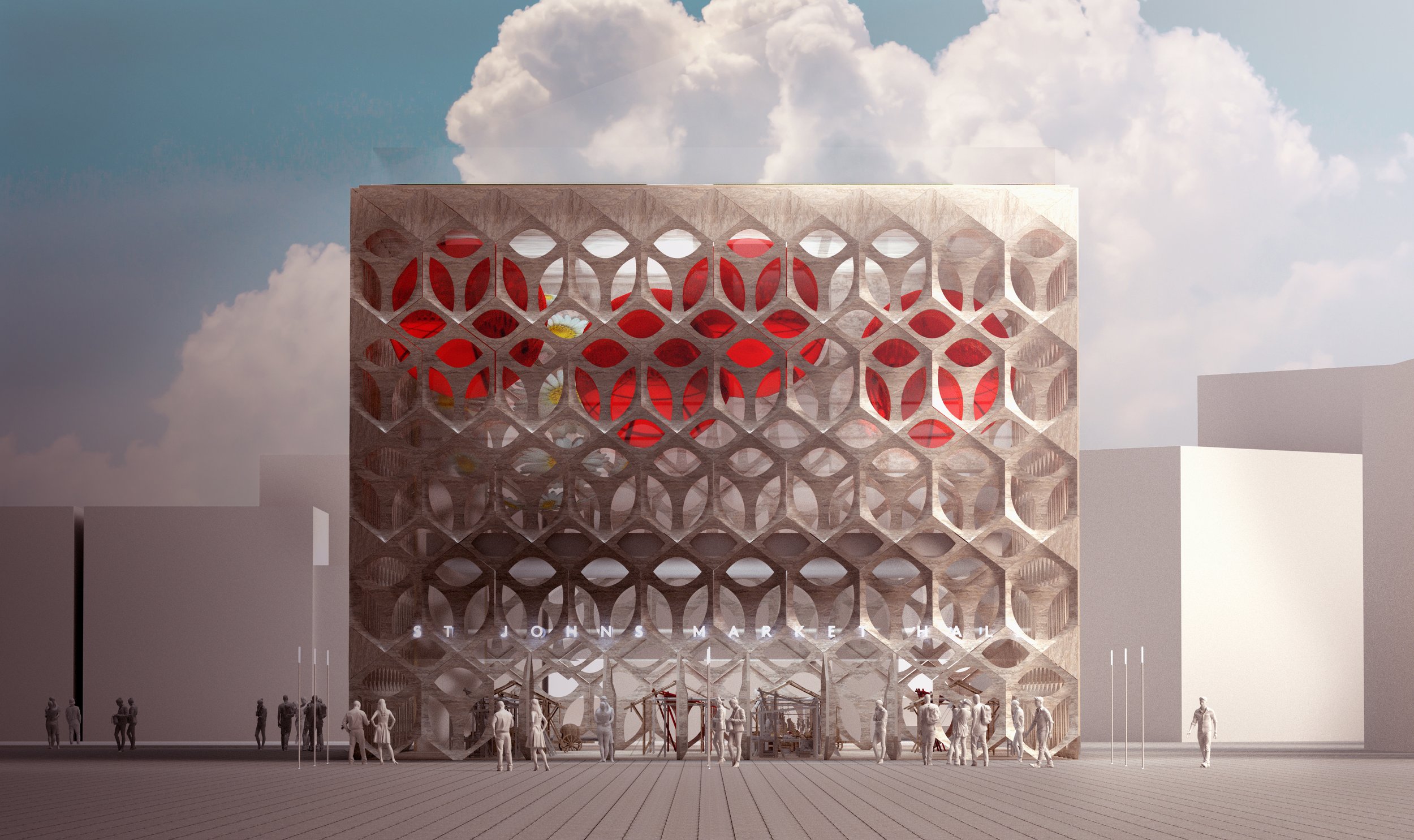

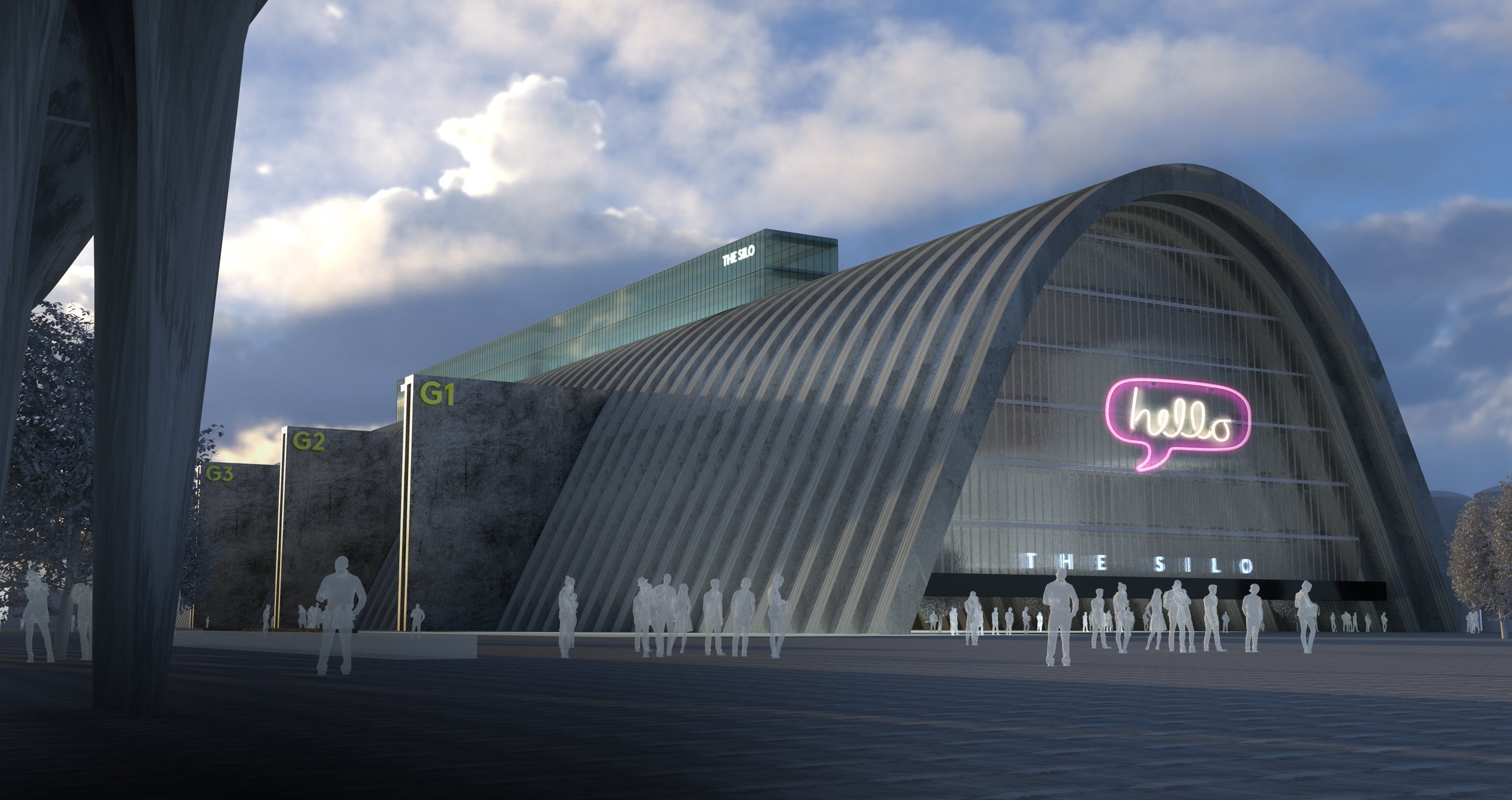

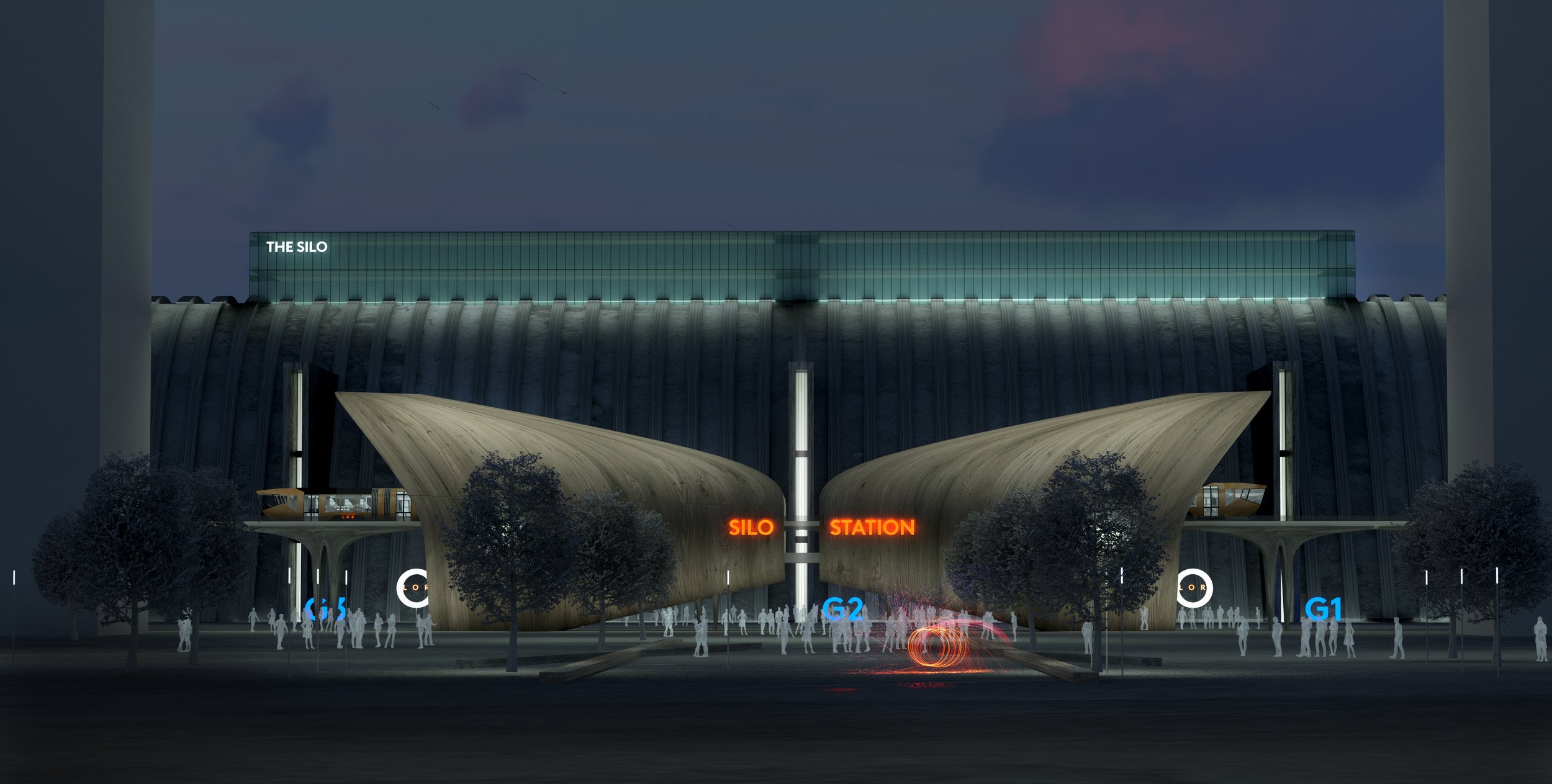

The content was a series of ideas offered or identified during our conversations with stakeholders, or arising from immersive wanderings around a town rich with unique and under-utilised assets. The ideas included creating the region's best urban market, transforming the abandoned Dock Branch railway into Birkenhead's "low-line" and creating a venue for the town's burgeoning new music scene. In 2019 a Festival of Ideas, held as part of Wirral's Borough of Culture programme rehearsed these and other possibilities that would become the anchor ideas for the successful funding bids.

But with both the ideas and funding to deliver transformational change, doubts are emerging as to whether Birkenhead may once again squander a golden opportunity. Following a flurry of key officer departures, including Alan Evans, the Regeneration Chief widely credited with delivering the successful funding bids, concerns are growing that the Council lacks the organisational capacity and technical skills to translate tantalising visions into tangible realities.

‘…it’s something that people would be willing to get off a train for.’

More worrying still, it is now highly probable that pragmatic imperatives will lead to the abandonment of one of 2040's flagship projects. When visionary Dutch architect Jan Knikker was engaged in 2015 by Liverpool developers, ION, to feed into their Move Ahead, Birkenhead masterplan, the possibility of an urban market as unflinchingly radical as his Rotterdam masterpiece became a beguiling statement of ambition. After all, Birkenhead had been a market town, and a re-imagined, relocated modern urban market was the one thing Liverpool didn't have to offer. In the words of Birkenhead Councillor and Wirral Green Party Co-Leader, Pat Cleary, "it’s something that people would be willing to get off a train for."

Citing spiralling costs, the proposal for a new market on the site of the former House of Fraser store at the interface between the St Werburgh's Quarter and the proposed Hind Street residential quarter, would now appear to be dead in the water. A proposal to move the existing market traders into the former Argos store in the Grange Precinct, which is owned by the Council, is being presented as a smart value for money solution that turns a vacant liability into a source of much-needed revenue.

For Cleary, this would be more that the death knell of one of 2040's most transformational projects, it would signify, in his words the replacement of a genuine "regeneration perspective by an asset management mentality." For Cleary, the future of the market is emblematic. If one piece of a coherent jigsaw can be removed, where does that leave projects like Dock Branch Park that could just as easily begin to look expensive and expendable. His is not a lone voice, Birkenhead MP, Mick Whitley, called on the Council to reaffirm its commitment to the new market, warning that the revised option "would mean years of work up in smoke." Following a fraught Council meeting on December 6th, it appears these concerns are unlikely to be heeded. Although officers were instructed to investigate two other options including refurbishing the existing market hall, the House of Fraser site looks likely to remain a boarded up monument to failed ambition.

Others intimately involved in the evolution of the 2040 vision are also worried that the integrity and spirit of the 2040 vision could be lost in delivery. Liam Kelly, whose Make CIC organisation is a key partner in the delivery of the proposed creative hub in Argyle Street, is willing to accept the need for pragmatism, but favoured a less costly iteration of the existing plan on the proposed site, explaining, "it doesn't have to be expensive to look great." For Kelly, the litmus test for 2040 overall will be the Council's willingness to sustain the coalition of stakeholders and co-creators who have worked with the Council in shaping the vision. As the various funding strands are blended and the overall delivery architecture is refined, Kelly believes, it's about "having the doers around the table and how difficult decisions are made" that will safeguard the integrity and deliverability of the 2040 blueprint.

‘Seeing the tragic and seemingly inevitable decline of the once vibrant Victoria Street, local entrepreneur, Dan Davies, embarked on a uniquely eccentric and joyous regeneration adventure.’

With a final decision on the market project now scheduled for February, the omens point increasingly in the direction of Argos. Both Cleary and Kelly stress the much bigger picture perspective that is somehow absent from the beancounting calculations underpinning the Argos proposition. Without a radically different and vibrant Birkenhead town centre, the viability and credibility of plans to build thousands of new homes on brownfield land at Hind Street and Wirral Waters becomes highly questionable. With Leverhulme Estates already launching a legal challenge in support of their plans for 800 greenbelt homes, the pressure on the Local Plan, and the fragile political consensus underpinning the Left Bank idea, may begin to exhibit destabilising cracks and fissures.

Away from Birkenhead there is another equally worrying indicator that when push comes to shove, pragmatism and asset management logic may be taking precedence over a commitment to the Left Bank aesthetic. There is no known precedent or template for the extraordinary regeneration story of Rockpoint and New Brighton. Seeing the tragic and seemingly inevitable decline of the once vibrant Victoria Street, local entrepreneur, Dan Davies, embarked on a uniquely eccentric and joyous regeneration adventure. Buying up empty and semi-derelict shops, he commissioned internationally renowned street artists to execute a series of spectacular murals celebrating the history, culture and identity of the town memorably dubbed, The Last Resort, by photographer Martin Parr.

This was not just about a lick of paint or a superficial facelift to cheer the spirits. Davies's restless energy and obsessive Canute-style audacity has reversed the tide of decline by bringing new businesses, cafes, venues, an art gallery, pub, recording studio and performance space to make Victoria Street possibly one of the most visually and creatively eclectic high streets in this part of England.

With an offer that caters for every demographic - from disadvantaged young people to socially isolated older residents - the breadth of Rockpoint's improvised and quirky inclusivity was perhaps most perfectly expressed in Hope - The Anti-Supermarket. Occupying the thrice-failed food store, Rockpoint transformed the unit into a multi-use space for artisan and independent retailers, social events, comedy, music and local am-dram performances. At a time when communities everywhere are witnessing a diminution of social capital and public space, Davies was delivering, under one roof, the kind of outcomes that 2040's proposed "creative" and "wellbeing hubs" can only promise. In a baffling decision, Wirral Council chose not to extend Rockpoint's tenure of the building, opting instead for the revenue rewards of a hardware store. Hadn't they read the magazine?

The Left Bank idea is an astute piece of positioning, and with an intelligently targeted and resourced campaign, it’s a necessary component in differentiating Wirral's offer, and guiding its regeneration direction. But the Market and Anti-Supermarket case studies also highlight the fragility of mood board-based regeneration, especially when those ineffable and immeasurable subtleties don't convert easily into the hard currency of public sector fiduciary imperatives.

But perhaps there is another flaw in a strategy that fails to distinguish between necessary and sufficient causation. Paris's Left Bank is not simply the bohemian haunts of the Latin Quarter and St Germain-des-Pres and nor is London's South Bank just Borough Market and its trendier residential enclaves. To return to Pat Cleary's challenge, what will make enough people get off the train, or even decide to put down roots in the new urban neighbourhoods envisaged in Birkenhead and the Left Bank? To be more than the One-Eyed town, doesn't Birkenhead need (and deserve) its equivalent of The Musee D'Orsay or Tate Modern? At the conclusion of the Manifesto for Downtown Birkenhead, we posed a question - shouldn't the town that invented public parks and pioneered mass transit reclaim its capacity for innovation and ambition?

“Important places are home to important institutions.... Far from being frightened of big ambitious ideas, we need to encourage them, test them and ultimately deliver them.”

Does 2040 lack the scale of ambition and impact necessary to deliver the catalytic stimulus that Birkenhead requires? Conceiving and delivering projects of that magnitude (including the discreetly mooted V&A of The North) and integrating and re-balancing the two banks of what a casual visitor might mistakenly believe to be one city, is a task that probably necessitated the invention of a City Region and a Metro Mayor.

In fairness to Wirral, the authority has been especially ravaged by the impact of austerity, hollowing out its core capacities and stretching services to breaking point. This is a difficult time to navigate the uncharted terrain of delivery, and the pressure and temptation to find pragmatic compromises may be difficult to resist.

In difficult and demanding circumstances, Wirral has formulated a complex and highly integrated planning and regeneration prospectus, an edifice where big picture objectives are founded on detailed and precisely crafted plans and projects. When Councillors meet to make a final decision on the future of Birkenhead Market in February, they may need to consider whether this is the moment to play a particularly precarious game of jenga?

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

*Main image: Eszter Imrene Virt, Alamy

Genghis Khan, Kirkby Market and me

Since the 1990s, the town of Kirkby, a suburb of Liverpool has undergone a continuous cycle of demolition and reconstruction. The changes, though well intentioned, have largely failed to address Kirkby's social problems or arrest the high rates of deprivation. Regeneration expert, John P. Houghton, who was raised in the town, recounts Kirkby's regeneration history and argues that the social cost of change has often not been worth the price.

John P. Houghton

From rural village to manufacturing powerhouse to struggling suburban overspill, Kirkby has had a chequered history. Just 6 miles from Liverpool, in the borough of Knowsley, the town was once the inspiration for the TV show Z-Cars, a police procedural majoring on social realism in gritty estates.

In recent years, Kirkby has seen some degree of investment, from new housing and schools to a brand new market and health centre, and it recently acquired a new train station. Artwork is layered around the town’s centre including winged chairs and a wise, old elephant riding a Viking longboat. But the picture remains mixed. Hope for better rubs shoulders with as yet unfulfilled promises, marked by peeling hoardings and discarded shopping trolleys. The one thing you can say for sure is that Kirkby is increasingly unrecognisable, with planners consistently favouring demolition and rebuild over subtler forms of intervention.

One man who would know is John P. Houghton, a regeneration expert who grew up in the town. In this article, he argues that the hard lessons from Kirkby’s past need to be applied to its future - that people should come before property. John believes keeping communities together and repairing the social fabric is better than constantly demolishing and rebuilding estates…

In the year 1218, the Shah of Khwarezmia made one of the worst decisions in all of human history; he picked a fight with Genghis Khan.

The Mongol leader had made a tentative peace-with-trade offer to the Shah, the ruler of a vast Central Asian empire, by sending a caravan of ambassadors to negotiate an agreement that would allow both medieval superpowers to co-exist. In response, the Shah killed the emissaries. Khan was so enraged by this act of provocation, he immediately declared war on the Khwarezmian empire and its unwise leader. Victory on the battlefield was swift, although the Shah himself escaped and fled.

Without his enemy’s body for proof of his conquest, Khan ordered his men to the Shah’s hometown, where they demolished and dismantled every single building until no structure was left standing. Even this was not enough to satisfy Khan’s desire for retribution.

His troops went on to re-direct a local river through the place where the town once stood, washing away the last stumps of human settlement and wiping the Shah’s birthplace from the map.

While the course of Merseyside’s River Alt is probably safe, I sometimes wonder if I’ve done anything to provoke similar wrath from the planning department that oversees my hometown of Kirkby in Knowsley. Let’s look at the historical record.

Here’s a list of the now-demolished buildings that played an important part in my early life: the estate where I was born and lived to the age of four; my infant school; my junior school; my secondary school; the church where I took my first Holy Communion; the swimming baths where I dived for rubberised bricks in my pyjamas; the sports centre with its infamous ski slope; the library; he college where I did my first work experience on the local newspaper; and the ‘Mercer Heights’ tower block where my uncle lived which offered views all the way to the Mersey.

One of the few buildings from my childhood still left standing is the house where I lived until I left for university at the age of 18. But don’t get your hopes up; this is not a pinprick of light amongst the darkness. The place I called home will make an unhappy appearance later in this story.

Tales of bloody vengeance aside, there is perhaps another explanation why my hometown has been involved in this seemingly endless cycle of estate clearance and re-construction. It’s an explanation that exposes the folly of putting property before people.

To understand that story, we need to take a look at the history of Kirkby.

Kirkby has seen investment in recent years but vast tracks of land are still hidden behind ageing hoardings. A local resident complained about ‘broken promises’ over a new cinema. Image: Liverpolitan

Over-spill

In 1951, Kirkby was a village of 3,000 people on the eastern fringe of Liverpool. Nearby, the government had built the Royal Ordnance factory to supply munitions to British troops during World War II. This had seen an influx of 20,000 temporary workers during those war years but the village itself had remained largely unchanged, with its rural economy sustained by the fertile soil of the surrounding farmland. But all of that was about to change utterly and at phenomenal speed. In the years that followed, Kirkby would grow at a pace barely seen in England since the Industrial Revolution.

The transformation was driven by the UK’s post-1945 approach to urban and economic development. As in other places such as Coventry and Plymouth, vast tracts of Liverpool had been destroyed or heavily damaged by the German Luftwaffe. For urban planners facing the challenge of rehousing both industry and tens of thousands of workers this opened up untold opportunities to realise their utopian civic dreams.

Post-war government policy subsidised clean-sweep demolition and the dispersal of populations out of cramped, bomb-ravaged city centres and into gleaming, structured ‘new towns’. Kirkby, with its ample land, brief flirtation with mass production and proximity to the city, was viewed as a prime spot to begin construction.

“The people who created Kirkby could build houses, but chronically undervalued the importance of ‘third places’, where people of all ages can rest, relax and play.”

Southdene was the first estate to be built in the new town in 1952, and was followed by many, many more. Although, as we’ll see, it took longer to deliver social and cultural amenities than it did new houses; the first shops were not opened until 1955, while the first pub only began serving in 1959. Kirkby Market started trading a year later.

By 1961, the population had rocketed from 3,000 a decade earlier to 52,000; a seventeen-fold increase in ten years. My grandparents, as children, were part of this vast wave of managed migration. Young families were attracted not only by the prospect of a home with a garden, but good chances of employment too. Liverpool City Council had bought the old Royal Ordnance site and working with factory owners and manufacturers had redeveloped it as Kirkby Industrial Estate. The future looked rosy.

However, the immediate problem on “Merseyside’s largest over-spill estate” was the absence of social infrastructure or, in simpler terms, the lack of anything to do outside of the house. Especially for the huge numbers of young people who lived there.

Tower blocks like Mercer Heights have been disappearing for years. But the new housing has merit if not the same great views. It will, however, take time to build back a lost sense of community. Image: Liverpolitan

“For building’s sake”

By the early 1960s, virtually half (48%) of the Kirkby population was aged under 15. The average for England was just over a quarter (27%). If you find buses or trains quite noisy when half the passengers are school kids, imagine an entire town like that. All of the time, with practically nothing for them to do.

Demographic imbalances are understandable in the post-war context. After all, around 880,000 British soldiers, or 6% of the nation’s adult male population, had shed blood on the battlefield in WW1. Another 384,000 died in WW2.

Less comprehensible is the failure to anticipate the consequences of concentrating thousands of families in a new town without support structures or social amenities. In his blog piece, New Jerusalem Goes Wrong, John Boughton cites a 1965 article in The Times: “no-one has yet built a cinema or dance hall and, possibly for this kind of reason, the 13 and 14-year old are the town’s most frequent law-breakers.”

On the same theme, one resident complained of the local council that “all they’ve built for is building’s sake but not to take the children into consideration. Have a look around here, where on earth can children play?” The people who created Kirkby new town could build houses, but chronically undervalued the importance of ‘third places’; spaces outside the home and workplace where people of all ages can rest, relax and play.

Even reforms to how the town was governed failed to deliver a change in thinking. The Kirkby Urban District, which had been established in 1958, was abolished in 1974 and merged with nearby authorities to form the Metropolitan Borough of Knowsley.

The new structure delivered the same old emphasis on volume housebuilding at the expense of essential infrastructure. Perhaps the new authority’s ambitions were thwarted by an infamous episode in Kirkby’s history.

Sloping off

The new Borough council may have been put off the idea of building anything other than houses by the experience of trying to instal a ski slope in the grounds of Kirkby sports centre. This is one of the oddest, and still most mysterious examples of urban misadventure in England’s post-war history.

The idea, first formulated in a smoky pub in 1973, was to offer residents the chance to get some exercise by emulating the professionals on the BBC’s popular winter sports show, Ski Sunday. In reality, neither the planners nor the contractors knew how to build a ski slope in a built-up urban environment. This most basic fact may have been exposed if the building contract had been put out for open and competitive tender. However, due process was almost completely ignored as deals were done over lunchtime drinks.

“An internal inquiry at the council, found that the [ski] slope had been built “without planning permission, over a water main, on land the council didn’t own. Due process was almost completely ignored as deals were done over lunchtime drinks.”

Costs spiralled as, during safety trials, both people and parts of the slope kept falling off. This required the addition of boundary fencing and frenzied attempts to ‘de-bump’ the surface; all to no avail.

The bumps may have been caused by the “haphazard collection of builders’ rubble” used to make the mound, according to a jaw-dropping BBC Nationwide investigation. This prompted an internal inquiry at the council, which found that the slope had been built “without planning permission, over a water main, on land the council didn’t own.”

The worst allegation was that the slope had been built the wrong way around, threatening to send terrified skiers into the path of oncoming traffic on the M57 motorway. Amid howls of derision, and before it was completed, the council stopped further construction in 1975 and, you guessed it, knocked it down.

Unlike the Kirkby skiers, the local economy was initially heading in the right direction. The teenagers may have been bored, but the adults were kept busy. With a new workforce and modern factory plants, the early years of the town were an economic success story. By 1967, Kirkby Industrial Estate supported a mammoth 25,000 jobs. After the youthful exuberance of the 1960s, however, came the strife of the 1970s and 1980s.

Art designed to lift the spirits has been widely used around Kirkby. Some pieces are more successful than others. It’s unlikely the shopping trolleys were deemed worthy of a public commission, but their presence still speaks powerfully and artistically. Image: Liverpolitan

Demolition and depopulation

In 1971, the Ford factory at Halewood, south Liverpool, where my dad worked on the assembly line, laid off 1,000 workers in the middle of a strike over pay and conditions. Many more redundancies followed as factories were shuttered and workforces shrank in the face of competition and technological advancement. This included factories in Kirkby such as Thorn Electrical, which closed with the loss of 600 jobs.

By 1981 almost a quarter (22.6%) of Liverpool’s working-age population was unemployed. For the rest of that decade, and into the 1990s, Kirkby was trapped in a self-reinforcing cycle of job loss and population decline. The residents of the new town had been promised a New Jerusalem. In reality, as one Liverpool Echo report succinctly summarised, they were “let down by central government planners, corrupt councillors and the private sector alike”.

The loss of jobs and households was exacerbated by the council’s decision to use demolition as a primary response to neighbourhood decline. The BBC paid another visit to Kirkby in 1982, to report on the demolition of a large estate in Tower Hill.

As the newsreader Jan Leeming explained, the development had been built “only twelve years ago” but, according to the council, had proven unpopular and stood completely empty for the last two of those years.

As the estate is dynamited, the camera's unforgiving lens focuses on the destruction and the reporter reveals an equally devastating fact. The council will continue paying for the development for another forty years.

There was, no doubt, a case for demolishing the most unpopular and poorly-built developments, but in Kirkby, as elsewhere, widespread demolition became a self-perpetuating cycle; damaging the environment, breaking up communities, and effectively admitting failure in the task of making a decent place for people to live.

Demolishing entire estates also entailed the destruction of social and community facilities like shops, youth clubs, GP surgeries, and play areas that were already in short supply. In contrast, as a 2010 LSE research paper by Anne Power explains, refurbishment “offers clear advantages in time, cost, community impact, prevention of building sprawl, reuse of existing infrastructure and protection of existing communities.”

“In Kirkby, widespread demolition became a self-perpetuating cycle; damaging the environment, breaking up communities, and effectively admitting failure in the task of making a decent place for people to live.”

By the 1990s, central government policy became more sophisticated. The post-war policy of clearance and construction was falling out of favour. There was growing interest in the idea of comprehensive or ‘holistic’ renewal that paid as much attention to social infrastructure and public services as to bricks and mortar.

Down the road from Kirkby, the revitalisation of the Eldonian Village in North Liverpool won the prestigious World Habitat Award for its model of comprehensive, community-based regeneration. A core element of the approach was to keep the existing community together by repairing and improving the physical and social fabric.

A little further away, Urban Splash made its name in Greater Manchester by purchasing properties and as one president of RIBA wrote, “instead of demolishing them as others would have, they turned them into cool lofts and workplaces”.

Meanwhile, Knowsley council continued demolishing housing stock in Kirkby, including maisonettes and high-rise tower blocks, like Mercer Heights. While clearance and construction in other parts of the country were falling out of favour as a model of regeneration, closer to home it was still being used to spur short-term job creation.

“Driven by debt and speculation”

By 2001, Kirkby was home to just over 40,000 people, its total population continuing to slide down from its 60,000 peak in the economic heyday of 1971. I was part of that outflow, leaving for university in 1996 and returning only ever temporarily to spend time with my family.

In 2011, on one such visit, I drove past my old house, the one mentioned earlier, where I’d spent the majority of my childhood years. I was shocked to find that it was not only empty, but vandalised and partially burned out. I wrote about the situation at the time and it was picked up by Aditya Chakrabortty for The Guardian.

Home sweet home, but not as John remembered it. Time can be cruel. Image: John P. Houghton

The crash of 2008 and the harsh recession that followed had exposed the danger of relying on a fundamentally unstable and over-inflated housing market to drive economic growth. In effect, Knowsley Council, like others, had used housebuilding as a short-term economic stimulant.

When an area declined, clean-sweep clearance and new home construction was used to create jobs and generate economic activity in the immediate supply chain. But these gains were only ever short-term. When you factor in the disruptive social impact of this approach the cycle of knocking down and rebuilding ultimately becomes damaging and self-defeating.

This wasn’t building to make a community, but boosterism to stimulate a brief burst of economic activity in the absence of anything more sustainable or useful. As Chakrabortty put it, “places such as Kirkby remind us that what’s collapsed isn’t [just the economies of] a handful of countries, but an entire model of economic development: one driven by debt and speculation, which ignored the need for productive industry.”

“Kirkby reverses its fortunes”

Kirkby’s prospects for the next few decades are brighter than they have been for a while. After the re-opening of Kirkby Market, the Financial Times in 2022 described private sector investment as “driving a retail revival in a deprived northern town.”

The Liverpool Echo came to a similar conclusion, citing data showing Knowsley “experiencing one of the strongest post-pandemic recoveries throughout the UK when it comes to local spending”. The council is exploring the idea of ‘community wealth building’ as a way to keep more of the money spent locally circulating within the borough’s economy.

The re-opening of the market was part of the long-running redevelopment of the town centre, which in turn is one of several investments in the town. A new train station, Headbolt Lane, opened in October 2023, connecting the Northwood neighbourhood to the line that runs straight into the centre of Liverpool.

If this recovery is to be sustained, the hard lessons learned from Kirkby’s past need to be applied to its future.

The profound social and economic costs of constant clearance and construction massively outweigh the short-term gains of using housebuilding to boost the local economy. Instead of widespread demolition and scattergun population dispersal, we should learn from projects that repair the social and physical fabric.

Neighbourhoods need more than just homes. They need pubs and parks, creches and community centres, libraries and lidos. Places that nurture a sense of community and give people the best environment to have a decent crack at life.

To ignore these lessons would be a folly worthy of the Shah of Khwarezmia.

Kirkby High Street on a sleepy Sunday. Images: Liverpolitan

John P. Houghton is a freelance consultant who works with councils, developers, housing associations, and community groups to make better places. A specialist in urban regeneration and economic development, John has advised the UK government on large-scale institutional investment in major projects. He was born and raised in Kirkby.

John regularly posts articles on his blog, Metlines in which an earlier version of this feature appeared. He can also be found on X (formerly Twitter) @metlines.

What do you think? Let us know.

Add a comment below, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Not So Red: Labour’s Slow Rise in the Scouse Republic

Liverpool wasn't always the ultimate Labour stronghold. For much of the past century, Conservatives have dominated local and parliamentary elections. Historian of the Left, David Swift, charts Labour's surprisingly slow rise to power in not-so-red Liverpool.

David Swift

You don’t often see Liverpool compared to Iran. And certainly a stroll through the city centre on a Friday or Saturday night brings sights you probably wouldn’t see in downtown Tehran.

In an essay comparing the politics of Iran and Egypt, the sociologist Asef Bayat pointed out that Egypt, despite having strong popular support for Islamist politics and a weak middle class, never established a religious theocracy along Iranian lines. The difference being that in Iran, the government of the Shah had successfully eliminated all secular opposition – liberals, socialists, trade unionists – so the Mullahs were the only people in a position to take over, despite a lack of broader support for their project. So Egypt had an Islamic movement but not an Islamic revolution, and Iran had an Islamic revolution without much of an Islamist movement.

Over the past 100 years something similar has happened in the political transformation of Liverpool. From a bastion of working-class Toryism, Liverpool has become a city with the five safest Labour seats in the country. Other areas with similar demographics have seen Labour’s support slide in recent years, but in Liverpool the party’s dominance has continued to grow.

Yet curiously, beneath the surface, just like in Iran, the dominant political movement has been anything but strong. Liverpool has undergone this Labour revolution with a much weaker, organised Labour movement than other cities. Don’t believe me? Look at the history.

This year marks the centenary of the election of Jack Hayes, the first Labour MP to sit for a Liverpool constituency – who won the 1923 Edge Hill by-election. This breakthrough came roughly two decades after other ‘Labour heartlands’ such as Manchester, East London, Glasgow, Leeds and South Wales had elected their first Labour MPs.

Before and even after Jack Hayes’ triumph, Liverpool was solidly Tory. From 1885 to 1923, with just a few exceptions, the city’s nine constituencies were won by the Conservative candidate in every parliamentary election. Toxteth was represented by people with little claim to working class roots; people with grand-sounding names such as Henry de Worms and Augustus Frederick Warr. It is hard to imagine now but for 14 years the MP for rugged Kirkdale was a Baronet called Sir John de Fonblanque Pennefather.

The most notable exception to Tory dominance at that time was the Liverpool Scotland constituency, centred on Scotland Road, which was dominated by Irish immigrants. Held by the Irish Nationalist T.P. O’Connor from 1885 until his death in 1929, his victory remains the only time a British parliamentary seat has been won by an Irish nationalist party outside the island of Ireland.

Of course, the Liberals had the occasional reason to celebrate too, winning Liverpool Exchange in 1886, 1887, 1906 and 1910 as well as Liverpool Abercromby in their general election landslide of 1906. But even at that election – a wipeout for the Tories and their worst result until 1945 – the Liberal Party only managed to win two of Liverpool’s nine seats, with the Conservatives taking six out of the other seven.

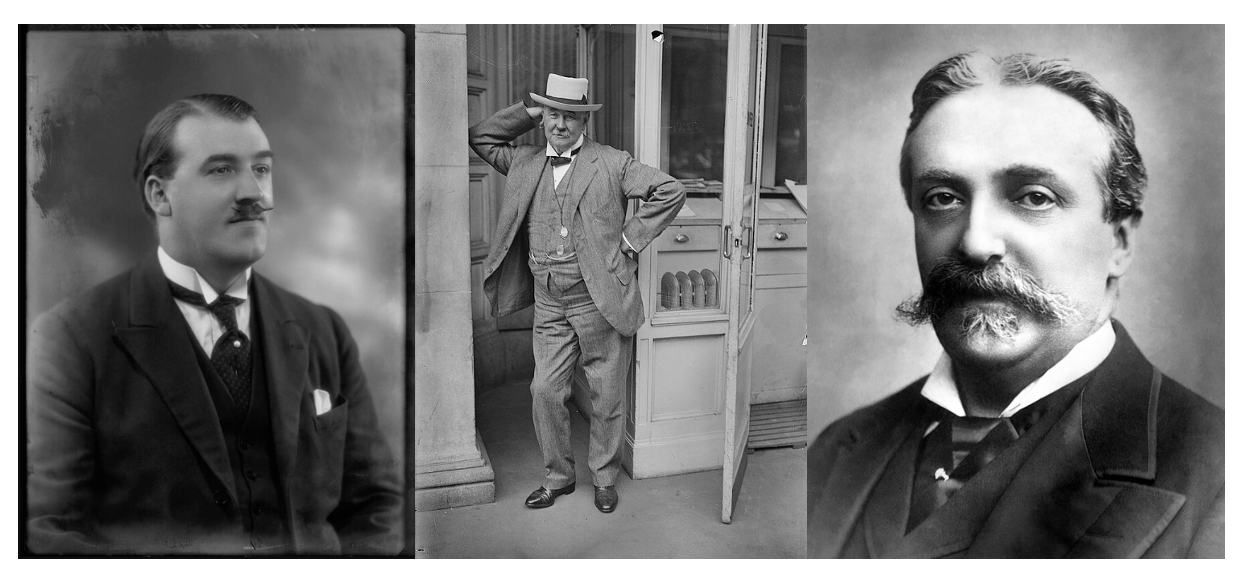

An Irish Republican, Tory Baron and Liverpool’s first Labour MP walk into a bar. But who’s who?

Left to Right: Jack Hayes Labour MP for Edge Hill (1923-31); T.P. O’Connor the Irish Nationalist MP For Liverpool Scotland (1885-1929); and Baron Henry de Worms, Conservative MP for East Toxteth (1885-95). Image credits in respective order (left to right): Bassano Ltd, public domain via Wikimedia Commons; Bain - Library of Congress (1917); Alamy

Some commentators have claimed Liverpool politics are based on rebelliousness or innate defiance and a willingness to speak up and go against the crowd. Which makes what happened in the 1906 general election all the more fascinating. Dominated by the issue of free trade, the Conservatives lost badly at the national level because it was feared their plan to impose tariffs on imported goods would damage trade. And yet even in this election, in a town as totally dependent on trade as Liverpool, even in a port city, Liverpolitans put two fingers up to the national trend and voted for the Tories anyway. Was this an early example of that noted tendency to contrarian defiance or slavish support for the party of power?

Of course, at this time, the six-year-old Labour party was not a serious force around the banks of the Mersey and their leader Ramsay MacDonald – who later become the first Labour Prime Minister, knew it too. In 1910, after a visit to the city he seemed to accept they had no prospects of winning there any time soon, writing with a note of sour grapes that ‘Liverpool is rotten and we had better recognize it’.

Why was Liverpool so slow to support the party of the working class?

One explanation often put forward is the narrowness of the parliamentary franchise which dictated who got to vote. It’s claimed voting restrictions prevented many working people from making their voices heard and it’s certainly true that this affected politics at this time, though perhaps not always in the ways most commonly understood. From 1867, men in ‘borough’ constituencies (usually towns and cities like Liverpool) were able to vote in general elections but only if they were defined as a ‘householder’. This meant a man living independently by himself or with his wife and children who also paid a minimum of £10 a year in rent. In theory, most working-class men could now vote, but in reality it’s estimated 40% of men nationwide were disenfranchised until these rules were relaxed in 1918.

This was because the lack of affordable accommodation meant many men still lived at home with their parents or in houses with multiple families, and so fell foul of the rule. In a port city like Liverpool, where seafaring was the second largest source of employment, this would have been particularly significant because so many men worked away for long periods. The 1921 census found there were twelve times as many men without a fixed address or workplace in Bootle than in St Helens.

Nonetheless, some historians have challenged the idea the franchise disproportionately affected working-class voters, noting that, on average, men from working-class backgrounds found work, left home and started families earlier than their middle-class equivalents. As noted by Neal Blewett in an article for Past and Present, middle-class professionals were more likely to be lodgers, who very often couldn’t vote. It’s too easy to use the disenfranchisement of working-class voters to explain Tory dominance in the city - especially since women, who have tended to favour the Conservatives by wide margins, were unable to vote in general elections until 1918. Perhaps the limitations on the voting franchise hurt rather than helped the Tories. In her influential book, The Iron Ladies (1987), journalist Beatrix Campbell claimed Labour would have won every election between 1945 and 1979 but for women’s right to vote.

The influence of sectarianism overstated

It’s also too easy to blame ‘sectarianism’ for Tory rule in Liverpool. According to this analysis, conflict between Protestants and Catholics divided the working class vote, with Catholics favouring ‘home rule’ for Ireland supporting the Irish Nationalist party (the IPP), while Protestants opposing greater Irish autonomy voted for the Conservatives. The argument goes that the conditions for a Labour breakthrough in Liverpool only occurred after Irish independence in 1922, when the sting went out of the nationalist cause. Catholic votes transferred to Labour, whilst Protestants, with the nationalist issue seemingly resolved, felt less inclined to vote Tory.

But many historians, such as Sam Davies, have downplayed the importance of sectarianism, arguing instead that Tory dominance resulted from the weakness of the Labour party in local politics and splits in the anti-Tory vote.

Famously, Churchill sent gunboats on the Mersey in 1911 to quell a dockers strike, but despite this Liverpool was still voting Conservative. Meanwhile in Glasgow … Red Clydeside was already represented in parliament. Image: HMS Antrim, Ernest Hopkins, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It’s instructive to compare the political situation in Liverpool to that of Glasgow - another town with a violent sectarian divide. While Liverpool outside of Scotland Road was staunchly Tory, in Glasgow, sectarian sentiment saw a surge in support for the Liberal Party. As far back as 1886, with the Liberal Government led by William Gladstone (a Liverpolitan), proposing Home Rule for Ireland under a less centralised United Kingdom, Catholic voters jumped at the opportunity to get behind the Bill. Nationally, the 1886 general election saw the Liberals lose over 150 seats as the issue proved unpopular. Yet in Glasgow, the Liberals won four of the city’s nine seats – with another two going to the ‘Liberal Unionists’ who, opposing the move, were no doubt supported by the city’s Protestants. Liverpool never saw anything like this degree of sectarian influence.

Back to that 1906 election, which by the way was only the second to be contested by the newly-formed Labour party. While Liverpool was busy voting Tory, in Glasgow, former shipyard worker George Barnes was elected as a Labour MP for Glasgow Blackfriars and Hutchesontown, a seat he held until he was elected for the new Gorbals constituency in 1918, alongside Neil Maclean, who won in Govan. By 1922, Labour was winning ten of the city’s 15 seats. In contrast, no Liverpool constituency elected a Labour MP until after the party had taken most of the seats in Glasgow.

“It is perhaps forgotten today, but back in the interwar years, the largest unions on Merseyside, the TGWU and the National Union of Seamen - representing dockers and sailors – had an inconsistent relationship with the Labour party.”

The importance of skilled workers and Nonconformists

One reason for Labour’s earlier breakthrough in Glasgow was its stronger concentration of skilled trades. Although like Liverpool, a major port, Glasgow relied less on distribution and more on the dominant industry of shipbuilding. This provided a stronger industrial base with many skilled jobs defended by well-organised trade unions. Even if we include the Cammel Laird shipyards in nearby Birkenhead, Liverpool never had a similar level of manufacturing jobs. There was far too much reliance on low-skilled, casual labour which was a lower priority for the wider trade union movement.

At this time, areas that voted Labour had either strong trade unions, or high levels of Nonconformist Protestants such as Baptists, Methodists, Quakers – or both. You can see this trend in places like South Wales, West Yorkshire, East Lancashire, and the Durham coalfield. Nonconformity was linked with moral and political liberalism: Nonconformists such as William Wilberforce had been prominent anti-slavery advocates, and were over-represented among critics of British imperialism. They also challenged elements of the British establishment such as the Church of England and the House of Lords. In Liverpool, however, the trade unions were small or weak, whilst most people were Catholics or Anglicans, with few Protestant Nonconformists.

It is perhaps forgotten today, but back in the interwar years, the largest unions on Merseyside, the TGWU and the National Union of Seamen - representing dockers and sailors – had an inconsistent relationship with the Labour party. In 1927, the Executive Committee of the Liverpool Labour Party (then known as the Liverpool Trades Council and Labour Party) was formed from clerks, postal workers, electricians, engineers, railwaymen, painters and insurance workers. Dressmakers, shop assistants, clerical workers, tailors and garment workers were all well represented in the membership – but representatives from the two dominant occupations in the city were conspicuous by their absence.

Tories still strong after World War 2 and the politics of normal

Even after the 1945 Labour landslide, the Conservatives continued to win elections in Liverpool. Tory MPs were elected for Walton and West Derby until 1964, and for Wavertree and Garston until 1983. At the 1959 local elections, six of Liverpool’s nine council wards were controlled by the Conservatives, and three of those were solidly working-class areas, including Toxteth and Walton.

During the 1970s, control of the council swung between the Tories and Liberals. When the Trotskyist Militant Tendency took over in 1983, they succeeded a Conservative-Liberal coalition.

When Labour was successful on Merseyside in this period it was not because of a strong local labour movement, but because political sentiment was tracking with the ‘normal’, with the city tending to vote in line with national trends

Speaking to political scientist David Jeffery, who studies electoral politics in Liverpool, he told me that after the Second World War there was a general trend towards the ‘nationalisation of politics’. By this he means that national rather than local issues became key determinants in deciding how to vote. Local politics began to matter a lot less, so the Liverpool vote tracked the national vote share. As elsewhere in the country, the party in power nationally would usually suffer in local elections.

As Jeffery explained, the Tory successes in council elections during the late 1960s were not driven by a surge in support for the Tories, but rather a collapse in the Labour vote due to the growing unpopularity of Harold Wilson’s Labour government in Westminster.

Then in the early 1970s, when Ted Heath’s Conservative government was unpopular, Labour and the Liberals did better in local elections, and in 1998, a year after Tony Blair’s Labour landslide, the Liberal Democrats once again took power of Liverpool City Council.

Prone to takeover – the problem with Labour’s low local membership

Even though there was a real change of the political culture and identity of the city in the 1980s, there was still not much of a labour ‘movement’. One of the reasons Militant was able to take over Liverpool Labour was because the local Labour party branches had relatively few members. They’d become hollowed out and simply didn’t have enough people to buttress against a well-organised and well-motivated sect.

Historically, in areas without strong trade unions there would be relatively few people in the local Labour party – put simply if you were not a union member or close to a union member you were far less likely to get involved with Labour. So once the unions lost their strength and influence from the 1980s onwards, alongside a decline in local government, the traditional working class routes into local politics dried up. Membership of Labour constituency branches (CLPs) in traditional working class areas has been on the slide ever since. As an example, the biggest constituency Labour parties today such as Hornsey and Wood Green in London have over 3,000 members, but one of Liverpool’s largest, Liverpool Walton, claims to have just over one thousand, and that might have been at the height of the Jeremy Corbyn membership surge.

One of the reasons Militant was able to take over Liverpool Labour was because the local Labour party branches had relatively few members. They’d become hollowed out and simply didn’t have enough people to buttress against a well-organised and well-motivated sect.

Just as in the early twentieth century, Liverpool today has a large working-class population, but it doesn’t have much of a labour movement – despite Labour consistently winning elections.

There have been well-supported social justice movements: such as during the dock strike of 1995-1998, the Hillsborough Justice Campaign, and more recently grassroots initiatives such as Fans Supporting Foodbanks. But this hasn’t translated into high membership or engagement with the Labour party itself.

Middle-class activists and the politics of identity

Labour’s membership surged under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn from just 198,000 in 2015 to 564,000 by 2017. But how many of these new members were from traditionally working class communities? Creative Commons C.C.0 1.0 via Wikimedia.

As far back as Tony Blair, commentators have noted how the ‘Islington set’ have become increasingly influential in the politics of the Labour party. People whose personal circumstances had taken them a long way from the traditional Labour voter were now shaping the party’s direction. During Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership in the 2010s, membership of the party grew, but often those new members were not from the traditional voter base. London, by comparison to Liverpool, has far higher levels of middle-class graduates and these are exactly the kind of people who have historically joined political parties. It’s not surprising that in places with more middle class voters, there’s been increased enthusiasm and engagement with Labour. But back in the Labour heartlands, not so much. This relative lack of enthusiasm and political engagement can be seen by comparing the turnouts of the last mayoral races in Liverpool and London: in both cases, everyone knew that the Labour candidate would win, yet in London the turnout was 40%, in Liverpool it barely reached 30%.

In recent years, the Liverpool Left has become more radical on cultural issues such as race and ethnicity - but it’s doubtful whether the city’s population is as liberal as their representatives on these issues.

The website, Electoral Calculus breaks down the demographics and political culture of each of the UK’s 650 constituencies, and ranks them according to their political opinion on economics (Left versus Right), internationalism (Global versus National) and culture (Liberal versus Conservative). It then uses cluster analysis to identify the influence of one of seven ‘Tribes’ in each constituency - including ‘Progressives’, ‘Traditionalists’, ‘Centrists’, ‘Kind Young Capitalists’, ‘Somewheres’, ‘Strong Left’ and ‘Strong Right’. It also estimates how each constituency seat voted in the Brexit referendum, a much finer grain of breakdown than exists in the official statistics.

Let’s take a look at how it assesses Liverpool’s five safest Labour seats:

Liverpool Walton - Traditionalist

27 degrees Left, 3 degrees Globalist and 1 degree Conservative; 52% voted Leave.

Knowsley - Traditionalist

26 degrees Left, 2 degrees Globalist, 2 degrees Conservative; 52% voted Leave.

Bootle - Traditionalist

25 degrees Left, 3 degrees Globalist, 0 degrees Social; 50% voted Leave.

West Derby - Traditionalist

26 degrees Left , 6 degrees Global, 1 degree Liberal; 48% voted Leave.

Liverpool Riverside – Strong Left

21 degrees Left, 29 degrees Globalist and 18 degrees Liberal; 27% voted Leave.

As you can see, the top four constituencies are classed as ‘Traditionalists’, according to the Electoral Calculus formula. The people in these seats have, on average, left-wing economic views but cultural and social views that are centrist or conservative.