Recent features

Eurovision 2023: Liverpool’s Imperfect Pitch

When Liverpool won the right to host Eurovision 2023 on behalf of war-torn Ukraine, most people in the city celebrated. With its reputation for music and for fun nights out, allied to its compassionate heart, the city was seen as the perfect fit in difficult times. But some have warned that in mistaking kitsch for cool Liverpool risks reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of its cultural brand. Jon Egan wonders how we can subvert expectations to deliver on the European Song Contest’s higher purpose.

Jon Egan

Amidst the near-universal jubilation at Liverpool’s successful bid to stage Eurovision, I struggled to suppress an almost inchoate feeling of dissident cynicism. Is the European Capital of Culture now pitching its future identity on an ambition to be the European Capital of Light Entertainment?

Liverpool is a perfect fit for Eurovision we are told by the bid’s architects and cheerleaders, though this natural synergy with an event that was until very recently derided as a festival of musical mediocrity is at the very least an arguable proposition. No disrespect to Sonia (creditable second) and Jemini (nul points), but they are rarely name-checked when the city intones the sacred litany of its popular music icons. As travel writer and destination expert, Chris Moss opined in his recent Daily Telegraph article; “From Echo and the Bunnymen to The Farm, from The Mighty Wah to The Lightning Seeds, pop and rock culture in Liverpool has always been anti-establishment, iconoclastic and often disdainful of national media-driven circuses."

I’m old enough to associate the Eurovision Song Contest (as it was called once upon a time) with Katie Boyle, a BBC stalwart and actress whose deft professionalism and elegant gentility made her a perfect fit as TV host for an earlier incarnation of the continent’s festival of song.

I’m not quite old enough, however, to remember, what is now my favourite ever Eurovision-winning performance, France Gall’s weirdly off-key rendition of Serge Gainsbourg’s ironic masterpiece, Poupee de Cire, Poupee de Son. Yes, there was irony at Eurovision long before Conchita Wurst or the knock-about stage-Irish buffoonery of the late Sir Terry Wogan.

Eurovision’s durability is doubtless its capacity to adapt to the changing mores of social convention and popular culture, not to mention the seismic disruptions to the boundaries and very identities of its competing nations. Which of course, takes us to 2023 and a Eurovision overshadowed by the tragedy of war in Ukraine. So it’s time for me to swallow my cynicism and recognise that this Eurovision is more than a celebration of blissful superficiality. Eurovision, which was conceived as an event to help bring a war-ravaged continent back together, has rediscovered a higher purpose and it’s up to us to deliver it.

There are already some encouraging signs. Claire McColgan and her team are planning an events programme that will celebrate Ukrainian culture in its many guises and remind the watching millions why this is happening here and not there. Liverpool’s Cabinet Member for Culture, Councillor Harry Doyle, told a gathering of stakeholders that he’s open to ideas about how the city can derive the maximum benefit and the most enduring legacy from next year’s Eurovision. So, if Harry wants my two penn’orth worth, here goes.

Whilst researching an article for the Daily Post sometime in the run-up to the European Capital of Culture, I asked David Chapple, a former Saatchi & Saatchi creative and regular visitor to the city, how he would market Liverpool. His answer was stark and challenging -“Stop telling people what they already know, surprise them!” I’m not sure that we have ever managed to live up to David’s exhortation. As Chris Moss warns, there is a danger that by claiming a perfect fit with an event that “mistakes kitsch for cool” we may simply be reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of Liverpool’s cultural brand. Moss, born and bred in neighbouring St Helens, believes that a city that should be the UK's foremost cultural destination is committing another branding "blunder" (having tossed away its World Heritage Status) by claiming an almost umbilical affinity with what he provocatively dismisses as a "naff, brainless extravaganza."

Moss's rhetoric may be extravagant, but there is more than a kernel of truth in the proposition that we have consistently failed to articulate and market the breadth and quality of our cultural offer. Ensuring Eurovision simply doesn't serve to reinforce a constraining stereotype, has to be a guiding imperative.

“There is a danger that by claiming a perfect fit with an event that “mistakes kitsch for cool” we may simply be reinforcing a narrow and trivialised perception of Liverpool’s cultural brand.”

So rather than being the perfect fit, let’s set out to design an imperfect fit. Let’s confound expectations, stretch the envelope and deliver a gathering that offers more than the “glitter and sparkle” that Doyle describes as the essence of Eurovision, but also explores what he terms (somewhat vaguely) “the added layer of Europe.”

I’m certain that Harry, Claire and their team are sincerely committed to ensuring Liverpool’s Eurovision acknowledges the wider European and specific Ukrainian context, although the confectionary metaphor suggests an application of icing rather than an especially bespoke cake mix. Surely now more than ever the “added layer” is the essence.

Returning to David Chapple and his urgings to surprise, the challenge to Liverpool would be how do we stage and wrap Eurovision in a way that confounds stereotypical perceptions of the city, that expands and subverts expectations while revealing a facet of unsuspected seriousness and cultural depth? Given the unique circumstances of this gathering, it seems like an appropriate juxtaposition to pitch the exuberant excess of Eurovision with a broader conversation and cultural exploration of the event's unsettling backdrop.

Notwithstanding Joanne Anderson’s excusable hyperbole that “the eyes of the world will be on Liverpool,” Eurovision 2023 will attract enormous numbers of visitors and serious levels of media attention. Liverpool needs to embrace the opportunity, and the responsibility, to do more than simply host Europe’s ultimate carnival of camp.

Are there media partners with whom we could convene a Eurovision of Ideas - a virtual or even physical gathering of thinkers, policy-makers and artists from Ukraine, the UK and Europe to explore how the shattering reality of yet another European war can help us to forge a deeper and more durable sense of solidarity and a shared future?

Is there space to stage an expo for Ukrainian businesses including their burgeoning technology sector, to help them forge new contacts and explore new markets?

For Ukraine, Eurovision has become a symbolic staging post in a journey from isolation and the cultural suffocation of the Soviet era. This war is a painful and bloody episode within the struggle for a new cultural and economic relationship with its estranged continent. So, how do we ensure that the celebration of Ukrainian culture proposed by Claire McColgan is sufficiently resourced to be immersive and integral and not merely a quaint window dressing for the main event? Culture Liverpool is bidding for funds to deliver a European-themed cultural programme, but an email to cultural organisations inviting bids was hastily withdrawn in the absence of any definite funding commitment from Arts Council England. These are early days, but this is not a positive omen.

In a recent conversation with me, journalist and commentator, Liam Fogarty speculated that if Manchester or Glasgow were staging this Eurovision, the scale of ambition might be greater and the prospecting for partners, funders and co-creators more lateral and imaginative. He is perhaps not alone in that thought. For the first time in nearly two decades, we have been successful in a major bidding competition, but what happens when the circus leaves town? What's our pitch to ensure a positive legacy and how do we create this event in a way that shows a previously unsuspected vista of a more interesting and multi-faceted city?

This is a huge opportunity to redress the imbalance of cultural investment towards London (and even Manchester) by demanding the resources to give a platform to the diversity of a resurgent Ukrainian culture, emerging from what contemporary poet, Lyuba Yakimchuk has described as a “war of decolonisation.” At the end of the day, we’re standing in for the place that would, but for the obscene brutality of Putin’s invasion, be hosting this event. So, let’s stretch every sinew and apply every creative impulse to celebrate the identity of a nation that a deranged tyrant is seeking to wipe off the face of the map.

And of course, we already have a connection and relationship with a Ukrainian city dating back to the early 1950s when Odesa was in the Soviet Union. In truth, Liverpool’s twinning relationship with the Black Sea port had become a largely hollow civic anachronism - a relationship long since packed away in the lumber room of municipal memorabilia. Until now, the cultural highlight of the twinning relationship was an impromptu concert by Gerry Marsden on the Potemkin Steps when the Merseybeat legend led an aid convoy after the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

“For the first time in nearly two decades, we have been successful in a major bidding competition, but what happens when the circus leaves town?”

For Odesa, threatened with invasion and subject to merciless missile strikes, friendship and solidarity have acquired a new and vivid resonance. Steve Rotheram's ambition to make Eurovision Odesa’s “event as much as our own” is generous and laudable but it will only be honoured by a substantial financial and imaginative investment and genuinely collaborative curation.

Without prescribing what a co-created cultural programme might look like, there is massive scope for stunning and surprising collaborations. One of the many intriguing (and sadly unrealised) ideas championed by the much-maligned Robyn Archer, whose brief tenure as Creative Director for Capital of Culture 2008 marginally exceeded Liz Truss’s occupancy of 10 Downing Street, was to stage performances by the Dutch National Opera in the semi-dilapidated grandeur of Liverpool Olympia. Notwithstanding Liverpool’s uncharacteristic failure to extend our famed hospitality to the soon-to-be homeless English National Opera, we could perhaps invite Odesa’s renowned opera company to be part of our Eurovision cultural celebration in their sister city. Whether at the Empire, Olympia (or even my long cherished dream to stage opera in the epic setting of St Andrews Gardens aka the Bullring), we could at the very least promise them a performance that would not be interrupted by air raid sirens or the rumble of distant explosions.

Sharing the Eurovision limelight with Odesa must be the beginning of a longer-term commitment to work with a city still under daily Russian bombardment. Beyond cultural and humanitarian co-operation, there may be a myriad of ways in which we can assist with trade and reconstruction. Even before the damage inflicted by Russian missile and bombing strikes, Odesa's Soviet-era port infrastructure was in dire need of investment and modernisation. Through a concordat for economic co-operation between the two cities, Liverpool should be using the exposure of Eurovision to gather together and broker the expertise and potential investment partners to help Odesa recover from the trauma and devastation of the present conflict.

All this may seem too ambitious, unrealistic or even unnecessary. At the end of the day, all that’s expected of us is that we put on a show, manage the organisation with reasonable efficiency and make an appropriate gesture to recognise the special circumstances of this Eurovision.

Maximising the opportunity and legacy is an undertaking that would require a massive collaborative effort with support from the UK Government, broadcasters, and cultural institutions here and in Ukraine. But without an initiative and impulse from Liverpool it will simply not happen. The unprecedented context surrounding the hosting of Eurovision 2023 demands exceptional effort and imagination, and we will never have a more morally compelling case for partners to match rhetoric with tangible resources.

For Liverpool, to quote Liam Fogarty, we should view Eurovision as “the starting block, not the finishing line” in the process of repositioning the city, building our cultural brand and answering the fundamental question posed in Chris Moss’s Telegraph article - what does Liverpool want to be?

Are we content to be the perfect fit, and use the Eurovision stage to repeat what the world already knows - that we’re a place that can deliver a great night out? Or will we use it to express the depth of our generosity and hospitality, the breadth of our imagination and the magnitude of our ambition?

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

It’s Time to Get Interesting

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to Manchester’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

Jon Egan

“Manchester, hub of the industrial north” was the opening line of a 1970s TV advertisement for the Manchester Evening News. With a voice-over by the no-nonsense, northern character actor, Frank Windsor, and what looked like shaky Super 8 aerial footage of an anonymous northern cityscape, the advert spoke to the city’s deep sense of itself as the very acme of gritty, grimy northernness.

This long-forgotten televisual gem was brought to mind by a recent tweet from Liverpolitan which observed, sagely, that when Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of his own city’s expanding psychogeography. Under Burnham’s monarchic reign, Manchester has become the fulcrum of an aspiring northern nation. Its status as capital of the north is beyond dispute. Michael McDonough’s visionary prospectus for Liverpool’s Assembly District as a home for pan-northern regional government (beautiful and inspiring though it is) is destined to remain another sadly lamented ‘what if’. Liverpool’s own claims to northern dominance are a boat that has long since sailed and, like a great deal of our city’s historic wealth and prestige, are now securely moored at the other end of the Manchester Ship Canal.

Sorry if this sounds fatalistic and defeatist, but it’s an unavoidable truth. Manchester as regional capital has already happened and I can’t help feeling it’s actually entirely apposite. Liverpool is not, never has been and never will be the capital of the north for a very simple reason - we’re not in ‘the North.’

Let me explain. Some years ago when pitching for the brief that became the It’s Liverpool city branding campaign, my agency team and I presented an extract from a speech by then Tory Minister for Transport, Phillip Hammond. In it, he had been extolling the benefits of HS2, which he prophesied would unleash the potential of “our great northern cities.” To emphasise the point, and presumably to educate his London-centric media audience, he decided to identify these hazy and distant provincial relics that would soon benefit from an umbilical connection to London’s life-giving energy and dynamism. Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Sheffield, Bradford and even Newcastle (which wasn’t in any way connected to the proposed HS2 network) all made it on to his list. Our pitch focussed on Liverpool’s conspicuous absence from Hammond’s litany. We weren’t (as I opined in an earlier offering to this publication) ‘on the map’. We deduced that the speech was one more piece of definitive evidence that Liverpool wasn’t considered sufficiently great to merit a mention - nor important enough to be connected to a flagship piece of national infrastructure. But on reflection, there may have been another reason for the city’s omission. Perhaps we weren’t sufficiently northern! As if the inclusion of the offending syllables liv-er-pool would have somehow derailed this Lowryesque invocation of smoke stacks, cloth caps and matchstalk cats and dogs.

Of course, we are not talking about The North as a geographic region, or even an amalgam of richly diverse sub-regions, but as a mythic construct. However, as the French philosopher and founder of semiotics, Roland Barthes, would argue, myths are always distortions, albeit with powerful propensities to overcome and subvert reality. In this sense, northernness is not merely a point on the compass - It’s a complex abstraction, a constituent part of the English psyche and self-image that has strong connecting predicates and excluding characteristics. Geography alone is not enough to discern where The North begins and which enclaves and exclaves are to be considered intrinsic to its essential terroir. Isn’t Cheshire really a displaced Home County tragically detached from its kith and kin by some ancient geological trauma?

Thus when Government Ministers or London-based media commentators pronounce on "The North" they are all too often referencing a cloudy and amorphous abstraction defined not by lines on maps, but by indistinguishable accents, bleak moorlands and monochrome gloomy townscapes, nostalgically referred to as ‘great cities’. From this perspective, northerners are seen as honest, hardworking souls, who used to make things (when things were an important source of wealth and national prestige). Though stoical and resilient, they have a tendency, every generation or so, to get a bit bolshy, at which point it becomes necessary to reassure them of their place in our national life by relocating part of a prestigious institution to a randomly selected northern location, or by staging a second-tier sporting event such as the Commonwealth Games or perhaps even placating them with some vague commitment to ‘re-balancing’.

“When Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham talks about ‘The North’, he is essentially delineating the outer boundaries of Manchester’s expanding psychogeography.”

Manchester has been brilliantly adept at securing for itself more than its just share of these charitably dispensed national goodies. Largely that’s through a typically northern resourcefulness and pragmatism, but also because the city has ingeniously positioned itself as a shorthand synonym for the very idea of northernness.

Peter Saville CBE, the graphic designer who art-directed Factory Records and designed their most iconic album sleeves, also created the acclaimed Original Modern branding for Manchester in 2006. A predictably beautiful piece of graphic creation, it wove a vivid palette of cotton loom colours to represent a new Manchester, that was proud of its pioneering past but wanted to take that innovative DNA to recreate itself in the 21st century. It was wildly popular, but as an exercise in “re-branding” it didn’t succeed in challenging or reframing Manchester’s perceived identity. Instead, it merely set out to transmute it into something more contemporary and serviceable. Saville's project was to dig deeper into the Manchester’s vernacular version of mythic northernness, reflecting no doubt his immersion in Factory's overtly industrial aesthetic. It’s a restatement of core northern traits and a celebration of the city’s long-established narrative - the hub of the industrial north. Manchester’s sense of modernity was less about today and more an evocation of the 19th century, when it was considered the workshop of the world. Its originality was brilliantly expressed by the historian, Asa Briggs, who described it as the “Shock City of the age” - an urban phenomenon without peer or precedent in Europe and only matched by Chicago in North America. Cut forward to the early years of the Noughties. The opening of the ill-fated Urbis project – a new ‘Museum of the City’, conceived by Justin O’Connor and designed by Ian Simpson, was a bold assertion in shining glass and steel of Manchester’s boast to have been the world's first industrial city and the birthplace of the modern age. Despite the powerful statement of brand identity, it was a hopelessly unsuccessful attraction, closing after only two years in 2004. Its director candidly admitted that this monument to the city’s inventive and industrious spirit simply “didn’t work.”

Peter Saville’s Original Modern. Despite the fresh lick of paint, Manchester’s new branding campaign was curiously backward-looking.

In my article, Vanished. The city that disappeared from the map, I suggested that one radical option for Liverpool was to stop trying to compete with its eastern twin. Instead, I argued, we could become a new kind of urban entity - a city with two poles, which pooled our joint assets and balanced the two hemispheres of human consciousness to forge a global metropolis that could re-balance Britain without needing to turn to the patronising benevolence of London. Two hundred years after the building of the world’s first inter-city railway between Liverpool and Manchester, it seemed like a plausible and timely possibility to explore. I was wrong. Not because this idea is manifestly an anathema and heresy to every patriotic Liverpolitan (except me, it seems), but because Manchester is definitively and inexorably set on its own northern trajectory (even to the point where its most creative and happening urban district is aptly branded the Northern Quarter). Unlike Liverpool, Manchester's identity is embedded in its geography, and its literal place in the world. Its compass has only one co-ordinate and it isn’t west.

So where does that leave Liverpool? If we’re not part of The North, where in the world are we? Exiled and dislocated from our northern hinterland, we are a place apart; liminal and strangely detached from mundane geography. The recent media frenzy occasioned by the booing of the national anthem by Liverpool FC fans reignited a predictably shallow rehash of the “Scouse not English" debate, with the now familiar allusions to Margaret Thatcher’s alleged but never conclusively proven project to euthanize the city, compounded by the tragic injustice of Hillsborough. But these events were not the beginning of Liverpool's estrangement from its northern and English identity and its gradual drift to the edge of otherness. When in the second half of the 19th century our “accent exceedingly rare” began to emerge as something radically different to the dialects of neighbouring Lancashire, it was disparaged as “Liverpool Irish” - a vernacular that was deemed to be both alien and inherently seditious. As late as 1958, in Basil Dearden’s film Violent Playground - a British-take on the then topical theme of “juvenile delinquency” - the Liverpool street gang, led by a youthful David McCallum, are portrayed with accents that one reviewer of the DVD release, observed, “curiously owe more to the Liffey (Dublin's river) than the Mersey.” We were quite literally being depicted as foreigners in our own country.

Struggling to find a place within the recognised cartography of northernness, with a figure and stature too grandiose for the peripheral space allotted to us, where in the world can we find a comfortable and fruitful niche? The city that disappeared from the map has only one option - find a new map!

“Liverpool’s cultural programme is undoubtedly worthy, but how many people outside the city can name a single event, festival or programme that happens here?”

Let’s call it the map of interesting cities - places with an ingenuity and energy that is not defined by their geography, and whose confidence and chutzpah aren’t predicated on being the capital of anywhere or anything. Cities whose identity isn’t camouflaged or submerged into anything as nebulous as a region or a point on the compass. So let’s concentrate on being seriously interesting.

It’s a mantel that fits our self-image but we need more than the costume. It’s a project that demands a script and some serious acting. I genuinely think that Liverpool is an interesting city, it’s just that for too long we have marketed ourselves on the basis of our most boring and predictable traits.

We could take our cue from Austin, Texas, a city that markets itself with the slogan “Keep Austin Weird”. It based its civic renewal project on a determination “not to be Houston.” Austin’s promotion of independent business and cutting-edge creativity made it an early poster-child for Richard Florida’s boho-city thesis that diverse, tolerant and culturally cool metropolitan regions will exhibit higher levels of economic development. But Austin’s claim to be an interesting city pre-dates the self-conscious cultivation of weirdness as a kitsch merchandising gimmick. Austin devised and delivered what is now one of the world’s most prestigious gatherings of music, film and interactive media creatives at the annual SXSW festival. It’s an object lesson on how to make space for a genuinely international and seriously ambitious cultural proposition and use it to re-position and redefine a city.

Have we really built on the exposure of 2008 to deliver an internationally recognised programme of cultural events? For all the self-congratulatory posturing, Liverpool’s cultural programme is undoubtedly worthy, definitely diverse but how many people outside the city can name a single event, festival or programme that happens here? For all the energy and inventiveness invested in our pell mell of festive gatherings, we somehow manage to deliver a cultural calendar that is considerably less than the sum of its manifold parts. Places that use cultural events as the pivot for their positioning strategy generally do so by delivering one event or festival of genuine international scale and quality, as Edinburgh, Venice, Austin, San Remo, Cannes and Hay on Wye amongst others will testify. Similarly, “cultural cities” or UNESCO cities of music will normally look to validate that title with a programme that is commensurate with their claim or status.

I’m not going to predict or prescribe the event or theme that Liverpool needs to devise because there are bigger and better informed brains than mine who will be needed for that task. However, I do believe this city can build and sustain an international profile compatible with its brand and reputation by aiming higher and deploying its resources accordingly. For Austin, SWSX was not a travelling circus; it was an integral part of the city’s emergence from the shadows of Houston and Dallas to find its own profile and authentic magnetism. (For more information on Austin’s struggle to maintain its cultural identity try Weird City by Joshua Long).

Being interesting is a vocation. It demands creativity as well as rigorous discipline and hard work. It inevitably requires a style and quality of leadership that is absent from our dismal and discredited local politics. It’s ironic that the one aspect of our civic life that is without question unique and interesting, is so for all the wrong reasons. Liverpool's politics never fails to entertain, shock, frustrate and confound - if only it could achieve and deliver. In the 19th century, Liverpool not only spearheaded ground-breaking projects in rail, building technology and maritime engineering, we were also a wellspring for innovations in public policy and governance. Through pioneering initiatives like the introduction of the district nursing service and public washhouses, and the appointment of the world's first medical officer of public health, Liverpool's civic leaders responded to unprecedented challenges with entirely original structures and solutions. At a time when so many of the established prescriptions and paradigms are breaking down, we need to be plugged into the people and places that are responding creatively to challenges like climate change, technology & the future of work, life-long learning, democratic engagement or the next global pandemic.

Being interesting has to be a behavioural norm that finds expression across every sector and constituency. Are our politics interesting or innovative? Is our media intelligent and stimulating? Are we nurturing our most inventive businesses? Are we doing anything original or brave to address our challenges in education, housing or transport? How do we hope to stem the migration of talent, potential and ingenuity as too many of our best and brightest conclude that this city simply doesn't offer them a future? How do we emulate cities like Austin and become a magnet for innovators and entrepreneurs rather than a departure lounge?

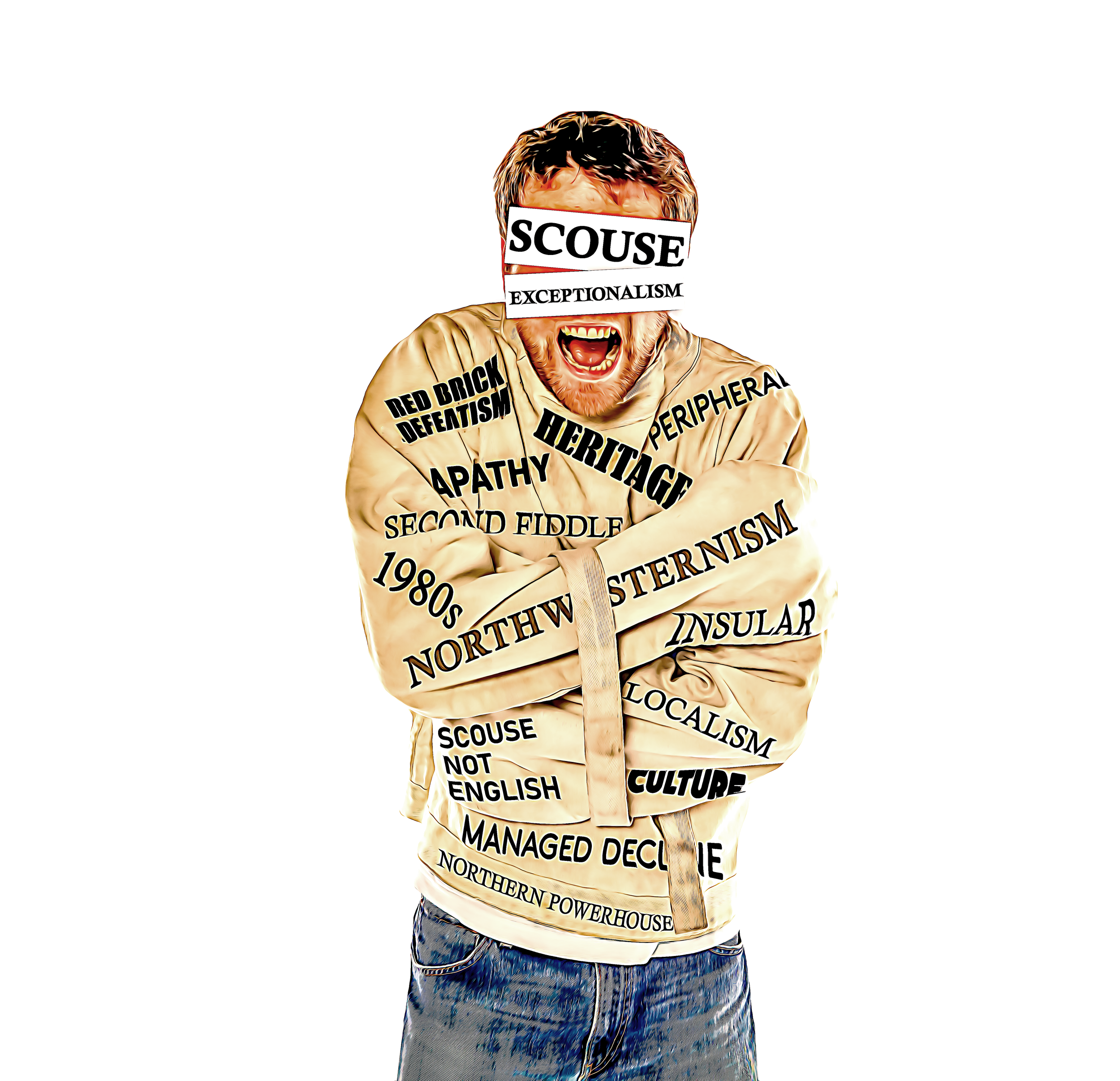

Being interesting is fundamentally about being interested and connected to the wider world! It’s about being aware of what’s happening outside the insular and constricting straight-jacket of scouse exceptionalism or parochial northernness. It’s being open to outside influences and ideas and forging connections and relationships with kindred cities. Maybe we could become the convenor of the interesting city network - a global family of midsize cities free from the gravitational drag of conformity and contingent geography? Cities like Portland, Rotterdam, Hamburg, Auckland and Vancouver whose commitments to liveability and sustainability has sparked inventiveness in transport, urban planning, smart technology and the cultural industries.

If there is a common trait or attitude that connects these cities it is that they are porous, with a capacity and willingness to absorb ideas, influences and people from outside and beyond. Their thinking and ambition is not stunted by a perspective that is either provincial or parochial. They have a place in the world defined more by attitude and outlook than their position on the map. More often than not, they are ports and portals for cultural and human exchange. Auckland and Vancouver have flourished as a direct consequence of immigration, welcoming industrious and ambitious migrants from South Asia and East Asia. Despite our boast to be the World in One City, Liverpool is one of the least demographically diverse cities in the UK. Having at last stemmed our population decline, we are still growing at a discernibly slower rate than comparable cities like Leeds and Manchester. So let's grow our population by becoming an overtly immigrant friendly city, and proactively targeting one potential migrant population with whom we already have an historic and cultural affinity. Doesn't it make sense for the home of Europe's oldest Chinatown to be promoting itself as a welcoming haven for Hong Kong residents fearful of mainland China's increasingly despotic designs on the former colony? "Hungry outsiders wanting to be insiders" was a phrase coined by West Berlin in the 1980s as a strategy to reverse demographic and economic stagnation. It's an approach that a city built for twice its current population could usefully emulate.

Our new narrative can be built on familiar and cherished aspects of (or at least claims about) Liverpool's core identity - open, welcoming and global. But it's time to live them rather than simply intoning them as glib marketing slogans and nostalgic musings. Brands are about behaviour; their truth and utility is measured by what you do, not by what you say, so let's be consistently and ambitiously global not provincial.

In the same way that we need to rethink and curate our cultural programme to be genuinely international in terms of reach and quality, we should be enlisting global talent and expertise to help us rethink and reshape our city. Rather than flogging off prime sites like Liverpool Waters and the Festival Garden to whichever developer or volume house builder is offering the biggest buck, let's hold an international design competition to deliver the most innovative and sustainable new waterfront communities. Twenty years ago, Liverpool Vision was able to excite architects of the calibre of Richard Rogers, Rem Koolhaas, Will Alsop and Norman Foster in opportunities at Mann Island and King's Waterfront. It's a tragic shame that none of their inspired visions came to fruition, but let's resolve to try harder and be clear and consistent about who we are and how we intend to renew and reposition our city.

It's tempting to imagine that being the Capital of the North will transform our destiny in a way that being European Capital of Culture failed to do. But it's not about titles. It’s about a fundamental change in disposition, attitude and culture - and finding a way to overcome the inertia and mediocrity that emanates from our moribund and discredited civic governance.

Above all, it’s about remembering that once upon a time we were the first world city - our compass is omni-directional.

Jon Egan is a former electoral strategist for the Labour Party and has worked as a public affairs and policy consultant in Liverpool for over 30 years. He helped design the communication strategy for Liverpool’s Capital of Culture bid and advised the city on its post-2008 marketing strategy. He is an associate researcher with think tank, ResPublica.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Referendum or bust – Liverpool’s last chance?

A discredited administration hamstrung by scandal. A weakened leader eyed by pretenders to the throne. A collapse of trust. And, underlying it all, a sense of drift and a loss of status in the world. For Boris Johnson’s Britain read Joanne Anderson's Liverpool. Both increasingly tottering on the precipice.

Liam Fogarty

A discredited administration hamstrung by scandal. A weakened leader eyed by pretenders to the throne. A collapse of trust. And, underlying it all, a sense of drift and a loss of status in the world. For Boris Johnson’s Britain read Joanne Anderson's Liverpool. Both increasingly tottering on the precipice.

Of course, it would be unfair to blame the city's current Mayor for more than a fraction of the woes afflicting Liverpool and its council. But her discarded pledge of a referendum to decide on whether to keep Liverpool's mayoral system was more than just another politician's broken promise. It was an affront to local democracy. The pitifully small response to the council’s subsequent governance consultation – just 3.5% of Liverpool residents replied - was inevitable. Launched in March, and conducted almost entirely online, the process was an artist's impression of a democratic exercise. The letter sent to each city household, directing its recipients to the Liverpool – Our Way Forward website, looked and read like a tax demand. Residents had 3 months to reply but a council taxpayer-funded "Have Your Say" supplement to promote the consultation was published with the Liverpool Echo on June 10th a mere ten days before the submission deadline. Perhaps if they were going to be this half-hearted they shouldn’t have even bothered. Its four vacuous pages contained plenty of room in which to set out the arguments for and against the various governance models on offer. Incredibly, it did not do so. An opportunity for meaningful engagement with Echo readers was spurned in what became a literal waste of space.

So what is to be done?

In his ground-breaking mayoral election campaign last year, as Liverpool absorbed the findings of the Caller Report into council misconduct, Independent candidate and eventual runner-up, Stephen Yip, called for a "re-set" of Liverpool City Council. He demanded top-to-bottom reforms in response to Caller's damning discoveries. The re-set phrase proved popular and was soon taken up by Labour's candidate, Joanne Anderson during her campaign. Once elected, however, she abandoned her commitment to resolve the mayoralty issue by means of a public vote, claiming a consultation would cost less than a full referendum which she deemed too expensive to justify. Since Joanne’s election, we have seen backsliding on the promises of more transparency and scrutiny of council business. Caller’s recommendation for a significant reduction in the number of councillors has been ignored, with the current 90 councillors being reduced merely to 85. Meanwhile, government-appointed commissioners now report that in several respects our council is going “backwards not forwards” in dealing with the issues it faces.

The loss of millions of pounds thanks to a botched energy contract showed systemic failings were not confined to the departments excoriated by Max Caller. There’s talk of more commissioners being drafted in, and more departments falling under their iron fist as skeletons continue to tumble out of closets. Not so much a re-set, then, as a return to politics as usual in Liverpool.

Stephen Yip and I agree that the first step towards an actual re-set is to let the people of Liverpool decide how their city should be led. Liverpool is local democracy’s ‘black hole,’ the only major city in England to have repeatedly denied its residents the chance to vote on how it should be run. The idea that Liverpool's citizens should be able to decide whether to keep or scrap the mayoral system is anathema to the control freaks at the Town Hall. Our politicians won't give us the mayoral referendum we are entitled to unless they are forced to.

Former Independent Mayoral Candidates, Liam Fogarty and Stephen Yip, launch ReSet Liverpool, a campaign to force Liverpool City Council to run a full referendum on city governance.

ReSet Liverpool

That’s why we are launching ReSet Liverpool, a petition-led campaign to give the people of the city the referendum they were promised. We reject the council's attempt to take such a huge decision on the city’s governance by itself. Options for the future running of Liverpool should be put directly to its residents at the ballot box.

Our petition aims to secure the 16,500 signatures (5% of the city's electorate) needed to trigger a referendum on whether Liverpool should retain the post of directly elected Mayor. A referendum held next May to coincide with scheduled elections for a Mayor and local councillors would come at minimal additional cost.

The final say on this issue should belong to the people, not politicians. It’s a matter of principle. Self-serving attempts to sideline the electorate are destructive. They weaken the already-strained connection between the people of Liverpool and their local council and lead to greater cynicism and indifference.

“The final say on this issue should belong to the people, not politicians. Options for the future running of Liverpool should be put directly to its residents at the ballot box.”

Without a referendum, Liverpool’s politicians are likely to revert to type. If they do move to abolish the mayoralty without public consent, then the simmering – and largely unreported - power struggles inside the council’s majority Labour group will burst open, absorbing the time and energies of all those involved. Mayor or no Mayor, in May 2023 every Liverpool council seat will be up for grabs on new electoral boundaries. As what is now 30 wards morphs into a whopping 70 smaller ones, once safe council positions will be under threat as councillors from the same party will be forced to compete with each other. The jockeying to be selected as candidates has already started and local parties’ fratricidal tendencies will be given full rein. The ward elections themselves will provide ideal conditions for the kind of hyper-local political warfare that appeals to party activists but no-one else. The chances of such a process producing a clear city vision, strong civic leadership and a coherent policy platform will be remote. Not for the first time, Liverpool politics will be all tactics and no strategy.

For ReSet Liverpool, a referendum on the mayoralty is the very least the people of this city deserve. May be it can also be the start of a broader campaign to reform our council and renew our city. If you are registered to vote in Liverpool, download a petition form (HERE) and if they live in Liverpool, get your friends, family and neighbours to sign up. Together, we have a chance to help kick-start that overdue process of civic renewal. It could be the last chance we’ll get.

Liam Fogarty is co-founder of ReSet Liverpool. A journalist, broadcaster and lecturer, he ran as an independent in Liverpool’s first Mayoral Election in 2012, finishing second.

Further Information

To find out more about Reset Liverpool and to download a copy of the petition, visit www.resetliverpool.org. Note: Only Liverpool residents over the age of 18 who are registered to vote can sign the petition. Completed petition forms should be returned to:

Reset Liverpool

301 Tea Factory

Fleet Street

Liverpool

L1 4DQ

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Introducing the Assembly District

History teaches us that no matter which party is in power in Westminster, only the north can be trusted to look after the north. But it should also teach us that the politics of agglomeration are divisive and will not end well for anyone but Manchester and Leeds. But never fear, Michael McDonough offers a solution - tearing up our current constitutional arrangements and establishing a new Northern Assembly for all of the north located on the banks of the Mersey. And he’s only gone and designed it … welcome to Liverpool’s new Assembly District.

Michael McDonough

Quite how Manchester Metro Mayor, Andy Burnham came by his coronation in the media as ‘King of the North’ is subject to conjecture.

Some such as journalist and author Brian Gloom speculate that it started as an internet meme, while others wonder whether it was a creation of Marketing Manchester, an agency never shy to position it’s home city as the centre of everything. Whatever its source, and Burnham has himself joked about ruling from a Game of Thrones-style castle, like all good observation comedy, its absurdity is centred on a degree of truth. You’d have to have been operating with your eyes closed since at least the emergence of David Cameron’s government in 2010, not to pick up the sense that Manchester has become the increasingly less unofficial capital of the north, much favoured by business, government ministers and media alike. It’s hard not to notice that whenever the north’s regional mayors get together for a photo op or conference, it’s Burnham that is usually centred as the pivot point around whom others orbit.

You could say this position is much deserved. Over several decades Manchester has played a very successful and canny game and has done much in the running of its economy that is both admirable and instructive to other regions with ambitions to raise their own performance. But this article is not intended as a Manchester love-in. The fear from the outside is that other regions, most notably its closest neighbour Liverpool, are caught in something of a gravity well, heading towards the event horizon, where the blackhole sucking in wealth and talent becomes inescapable.

The UK government appears to have been operating a policy known as agglomeration where the economies of towns increasingly centralise around cities, and the economies of cities are pulled towards the biggest and best of them. The idea is that a northern London will offer snowball effects that drive increasing productivity and opportunity. Any attempt to discuss the downsides are quickly dismissed as jealousy. But what happens to everywhere else? As any real political or investment efforts become increasingly centred on Manchester and Leeds, the north’s other towns and cities are forced to focus on more tertiary and lower value economic sectors to avoid this very obvious elephant in the room. No wonder there’s much discussion about transport. You need good trains and good roads to create a commuter belt.

Whether the north actually needs a ‘King’ is moot, it seems to be getting one, whether it likes it or not. In which case, maybe that King (or future Queen) really does need a castle or administrative centre from which to watch over their lands.

I’m being facetious, of course. But there is one idea that’s been doing the rounds for decades about the governance of the north that never truly goes away, even if no one has quite had the courage to turn it into reality. I’m talking about a Northern Regional Assembly or Parliament – a new constitutional arrangement that would put meat on the bones of devolution. I think it’s worth considering, for two reasons. Firstly, because history teaches us that no matter which party is in power in Westminster, nothing really changes for us. A Northern Regional Assembly would be founded on the simple understanding that only the north can be trusted to look after the north. And the second reason is that, done right, an Assembly could help to counter the divisive politics of regional capitals and agglomeration economics. Power could be distributed in a way that lifts up many communities, rather than few. For this reason an assembly must never be located in Manchester.

‘Let’s aim high. Consign talk of the ‘King of the North’ to the metaphorical dustbin and carve out a new sense of identity and purpose.’

I’ll leave the finer details to minds more attuned to the vagaries of politics and taxation, but it would almost certainly require a bonfire was made of existing local governance arrangements. This would not be yet another fatty layer of bureaucracy feeding off the twitching corpse of local democracy. It would be the pinnacle of a fundamental re-working of power – a place where the core cities and towns of the north would come together to fix and finance their priorities at scale. Cities like Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Newcastle joining forces with the Hull’s, Sunderland’s, Blackpool’s and York’s with one objective in mind – to challenge the economic pull of London and re-position the north as the economic engine room of the UK.

Maybe that sounds fanciful. Can we really reverse the economic gravity of the last 150 years? I don’t know the answer to that but I’d sure like to try. We should have some confidence about what is possible. Most of the UKs core cities reside in the north and our economy is bigger than that of whole countries such as Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, Portugal and Sweden. Our population is made up of 15 million souls and we account for about 20% of the UKs national GDP. While Westminster neglects to address the wealth inequalities that fuelled the demands for Brexit, isn’t it time we took power into our own hands and gave our region a stronger, collective voice? One where different parts of the north were incentivised to put aside regional rivalries and work together.

In which case, I’m going to ask you to imagine a world in which Liverpool becomes the focal point and home of that Northern Assembly. Is that really so far-fetched an idea? Some would immediately dismiss the prospect. Our council is after all essentially under special measures being guided towards competence by government appointed commissioners because we couldn’t manage it ourselves. What credentials do we have? But I’d simply say, why not? We may have had a politically turbulent history and a less than stunning present, but we also have a tradition in the last one hundred years of standing up for the many, not the few. Perhaps there is no more natural home for a regional assembly based on pan-northern equality and fairness as opposed to agglomeration, soft power and resource thirsty regional capitals.

Besides, despite all its issues, Liverpool is a city with an enviable international draw, incredible setting and bags of waterfront space to house such an assembly. A parliament might actually give Liverpool Waters some actual purpose too, while raising our own city’s aspirations. Some of our own will decry it as pie in the sky. But let’s not throw rocks or weave excuses. Let’s aim high. Consign talk of the ‘King of the North’ to the metaphorical dustbin and carve out a new sense of identity and purpose. One that is not only forward looking and aspirational but is also collaborative with its neighbours and based on a desire to see balance, fairness and justice intertwined into the north’s wider politics. it’s already there in the minds and hearts of northern people. Now let’s put it there in the institutions that represent us.

And so in the rest of this article, I’ve taken the liberty of going ahead and designing it. I hope you don’t mind the presumption but they do say a picture is worth a thousand words. I’ve created a series of visuals to conceptualise a new government district centered on Liverpool’s Central Docks.

Assembly District - Principles and Functions

Assembly District fly through.

Today, the site is owned by Peel Holdings and development plans are proceeding at a snail’s pace. A recent consultation was announced for some kind of canalside park, but it’s a blank canvass and no buildings have been announced. The creation of a new political ‘village’ or district laid out to intertwine with neighbouring developments such as Stanley Dock and Ten Streets could be the final piece of the jigsaw for Liverpool’s waterfront regeneration.

This new district would have to accord with some key functional imperatives and some core design principles. For function, the area must be able to accommodate our representatives and supporting administrative staff comfortably and securely. It must capitalise on the economic opportunity by creating desirable workspace which will be attractive to inward investment, and it must be broadly open to the general public to enjoy offering new facilities which are available to all.

From a design perspective, the development should be ambitious and contemporary, forward-looking, sustainable and transparent. This area should boast a ‘postcard design’ while being the embodiment of openness to enshrine in the built form the idea that our representatives work for us, not themselves or even their parties. A trigger for the designs should be northern solidarity. In addition, I’d like to create an element of pleasure through the creation of quality, yet surprising recreational space.

The Ten Streets and Central Docks area today

The Plan

Conceptually, the Central Docks plot would be divided into two areas: river and canal side to the west and further inland to the east. The waterside plots would feature the landmark structures and open space, while the east side could house complimentary mixed-use facilities including both work and residential schemes. Mirroring the adjacent Ten Streets grid pattern, the plans would see a series of new tightly packed, pedestrianised streets opening up the Central Docks site before reaching a series of new waterways and ‘blue spaces’ which will be reclaimed from parts of the site that are currently infilled docks.

New architecture on the site will be encouraged to straddle our quaysides, complimenting and working with water space rather than requiring for it to be filled in to create room for building. This in meant as both a symbolic and practical gesture of compromise in a city often at loggerheads with itself on how to reach for the stars architecturally without compromising existing heritage.

The centre piece of this new district would be the Northern Assembly building. Built across a series of pillars and positioned across the quayside to create a floating form, the building would be in a perfect position for security being largely surrounded by water and accessed only from one side. As a landmark for the north of England, the assembly would feature a circular internal layout to encourage parliamentarians to work together as one collective, while ensuring all areas of the north where represented equally. Cladded in steel and glass, with an undulating façade, the building would take some inspiration from Germany’s Reichstag building in which the public are free to observe parliamentary sessions as part of a commitment to transparency.

On the riverside of the Assembly building, a new public space would be built on a series of interconnected concrete pier structures inspired by Heatherwick Studio’s ground-breaking and beautiful Little Island Park in New York. Each of the up to 50 piers would represent core towns and cities as part of a linear park space on the water’s edge topped with attractive landscaping and robust Mersey-friendly planting. The piers are also symbolic of Liverpool’s position as an arrival and departure point for the whole of the north of England. Together with green spaces throughout the site, reclaimed and newly created blue space and interconnecting bridges this area would become a landmark open space for the city, a riverside space to think, debate, contemplate and engage with politics in a new heart of central Liverpool.

Two other landmark buildings neighbouring the Assembly are proposed for the water-side plot – one striking, multi-use cultural building and one mixed use 35-storey office and hotel.

The office and hotel building has been given a classic robot form with square body, head and antennae – this slightly retro but nevertheless futuristic form pointing to the need to put the industries of tomorrow at the heart of the north's strategy.

The form of the cultural building, which could house museums, exhibitions, performance and meeting spaces as well as a visitors centre, is modelled on a modern interpretation of Liverpool’s Anglican cathedral while it’s four brick turrets are an echo of the city’s landmark Liver Building. The overall effect is somewhat church-like to reflect the central role that faith and secular belief and moral values have in our communities and their deep historical roots in the region.

Transport

One of the key issues facing Liverpool’s central and north docks area is that of connectivity. To compare Central Docks to waterside redevelopment plots in London’s Battersea and Docklands areas it’s clear that a development of this scale and footfall would require a comprehensive transport strategy.

Conceptual design for Ten Streets station, Northern Line.

One possible solution would be the development of a station on the Merseyrail Northern Line to the western edge of the site. Built across existing railway viaducts and positioned equidistant between Moorfields and Sandhills. This new station could multiple audiences including the emerging creative Ten Streets district, Assembly District and also Everton’s Bramley Moore Stadium a few hundred yards north.

One of the key factors slowing down the regeneration of the north Liverpool docks has been access to the city centre and transport in general. Whilst a station at Ten Streets would go a long way to addressing this problem, the influx of new high density development may increase the viability of further transport infrastructure. The plans to the east of Central Docks envisage a concentration of high density homes and commercial and administrative buildings. The substantially increased footfall and employment in the area could support the creation of a new light rail link connecting directly with Lime St station through the currently disused Waterloo/Victoria tunnel alignment.

For illustrative purposes and to create a sense of arrival at the new Ten Streets station, I am proposing two wing-like structures addressing a new public square. Essentially abstract in form, they provide a modern interpretation of the industrial cranes that would once have been seen in the area. They also serve an important function, providing weather-proof covering for 4 escalators which take passengers up to the station’s platform level.

The Northern Assembly is the first of a two part article exploring the development of the Central Docks area. For our next article I will be exploring how the Ten Streets district itself could take advantage of Liverpool’s digital and gaming sector and if extended pull the area closer to the city centre.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

Child Labour

The latest local election results confirmed an ongoing trend – Liverpool’s councillors are being recruited at an ever younger age. But with low turnouts and widespread voter apathy, what does the emergence of ever more fresh-faced political candidates say about the health of Liverpool’s political culture? And should experience and proven competence trump youthful enthusiasm?

Michael McDonough and Paul Bryan

The latest local election results have confirmed an ongoing trend - Liverpool councillors (especially Labour ones) are being recruited at an ever younger age.

Sam East (Warbreck) and Ellie Byrne (Everton) both in their early twenties, join the likes of Harry Doyle (Knotty Ash), Frazer Lake (Fazakerley) and Sarah Doyle (Riverside) who became councillors at ages 22, 23, and 24 respectively (give or take the odd month – feel free to correct us). The latter three are now all serving in senior positions as part of the Mayor’s Cabinet.

Labour are not the only ones playing to this trend though. On the Wirral, Jake Booth, 19, took a seat last year for the Conservatives while in Liverpool the Tories recently appointed the frankly mature in comparison, Dr David Jeffery as their Chairman at the ripe old age of 27 (though he’s not a councillor).

The emergence of ever more fresh-faced local political candidates, which is often presented as energising and key to connecting with the city’s younger generation is nevertheless curious. Traditionally, solid life experience and proven competence in some other field of endeavour have been seen as valuable traits essential to making a decent fist of a job in public office. Demonstrable skills and previous success, which take time to accrue, have acted as a semi-reliable predictor that a candidate will land on their feet. But that kind of thinking is out of fashion. A fresh, young face is the recipe de jour.

Except it doesn’t seem to be working. The turnouts in the latest by-elections were abysmal- the puny 17% turnout in Warbreck putting the even more atrocious 14% in Everton to shame. Perhaps this should be a lesson that viewing politics though the lens of identity resonates far less than actually being credible.

None of this is to suggest that young people shouldn’t be in politics - far from it! And you could argue the older generation haven’t exactly pulled up any trees. Age and ability are not guaranteed bedfellows and we’ve all met unwise old-hands who are best left in the stable. But surely, even amongst the parroted outcries of ageism, track record counts for something?

The comments in the Liverpool Echo were a peach. “Shouldn’t those two be in school?” said one. “What life experiences can they bring to their roles. Jesus Christ!” said another. L3EFC expressed some doubt that “People fresh out of Uni” would be able to “stand up to the people who grease the wheels in this town.”

Which means we have to ask the question… can it be right that such inexperienced councillors are representing these deeply challenged areas which are crying out for leadership that can deliver on the ground? Will Councillor Ellie Byrne, the daughter of a sitting MP, deliver the kind of positive change Everton desperately needs? Does Councillor Sam East have the real-world nous to effectively tackle the issues holding back Warbreck? Or are these two eager and no doubt able politicians the product of a disinterested local Labour machine that doesn’t care or need to care about who it puts forward for election?

“The comments in the Liverpool Echo were a peach. ‘Shouldn’t those two be in school?’ said one. ‘What life experiences can they bring to their roles? Jesus Christ!’ said another.”

Of course, there are several reasons why young candidates are so attractive to party leadership. On the upside, they offer the classic and generally much needed injection of new blood. They hold out the potential for new ideas and new energy. And in Liverpool, where there is a dark shadow over much that has gone before, you can understand the desire to clear the decks and start afresh. But there’s another darker reason. Young councillors are pliable. They’re more likely to do what they’re told. While they’re still building their confidence, they won’t challenge the top dogs and that’s useful when your grip on power is weak. Mayor Joanne Anderson, herself relatively inexperienced as a councillor, has introduced young members to her Cabinet with responsibility for key portfolios including Development and Economy, Adult and Social Care, and Culture and Tourism. Without casting any aspersions on Cabinet members talents or potential, you can see their appeal.

We have to ask where the Liberal Democrats, Liberals, Conservatives and Greens are in all of this? Despite making admirable gains in many wards they still haven’t made much of a dent in the city’s ‘red rosette’ Labour strongholds and this despite the Caller Report offering them ammunition on a platter. As strong a campaign as the Green Party’s Kevin Robinson-Hale ran in Everton (albeit clearly under-resourced) he still only polled 362 votes. In Warbreck, the Lib Dems Karen Afford polled 874. This is not what engagement looks like. Perhaps it’s time all parties in the city took a long hard look at who they’re putting forward for local elections, what pledges are being made and why for the moment so many amongst the electorate simply couldn’t give a toss about what their local political parties have to say.

Ellie Byrne’s vacuous election promises were a case in point and a classic example of how an unengaged electorate enable party cynicism. Why bother getting too specific or measurable with your commitments when no-one is asking for it might be the rejoinder of the spin doctors, but it feeds the descent into low participation. A deeper critique suggests a more existential worry – our parties just don’t have any answers, scraping around in the bargain bin of ideas, and plucking out little more than platitudes of intention. Heaven forbid someone might actually come up with a plan to drive more employment.

It must be said in Liverpool the wheels turn more slowly. Many voters’ unflinching loyalty to party blinds them to individual failures, provoking little more than a shrug of resignation. Or worse, it depresses their sense of the possible. And that’s deadly, because if you don’t believe you can do much in life, the world has a tendency to deliver on your expectations.

But you can only hoodwink the voters for so long. When it comes to delivering results in the four years of office a councillor receives, competence beats willing nine times out of ten. A fresh face may serve you well enough amongst the cheap thrills of an election campaign, but does it really get the job done? Eventually, without the ideas or the know-how to deliver on them, you’ll get found out.

There is the temptation in Liverpool to think that little changes in the political sphere. That despite the odd bit of noise within the ruling party, on the outside all is stable and unchanging. A recent electoral modelling exercise suggested the upcoming 2023 boundary changes in electoral wards would have only the most superficial of effects. Labour, instead of holding 78% of council seats would now hold 79% it predicted. So much for turbulent times.

But bubbling away under the surface, something is happening and the results will be unpredictable. The recent by-elections were a warning, not just to Labour but to all parties. Sooner or later, voters will do what voters do. They don’t like being taken for granted.

All of this opens up a wider question about the city and its communities. Why are there so few people from a more professional background standing for election? What exactly is turning them off? Many of these people will be successful in their own lives. Could there be some really strong politicians and visionaries amongst the roughly 70% who don’t vote in local elections? Are there talented leaders amongst those Liverpolitans who look on at an unwelcoming, opaque and sewn-up political culture with distaste and disengagement?

Decades of brain-drain have undoubtedly had an impact. Liverpool has jettisoned so much of its professional class who left in search of opportunity they could not find at home. And now the parties are trying to fill the void by turning to ever younger graduates. If the trend continues we may well see in the coming years candidates organising their election campaigns around their GCSE examination calendar. An 18-year old Jake Morrison, who triumphed in 2011 over former Council Leader, Mike Storey to win the Wavertree seat may have well been a harbinger of times to come. He retired from politics aged 22.

Of course, at Liverpolitan, we always wish newly elected councillors well and hope to be pleasantly surprised by the new additions but we’d argue their election success is symptomatic of a much bigger elephant in the room, a room that clearly has fewer and fewer adults. It is a room dominated by established party complacency and a dash of arrogance; a city electorate detached from politics and a political culture devoid of real local talent and energy putting itself forward.

Michael McDonough is the Art Director and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a lead creative specialising in 3D and animation, film and conceptual spatial design.

Paul Bryan is the Editor and Co-Founder of Liverpolitan. He is also a freelance content writer, script editor, communications strategist and creative coach

Share this article

What do you think? Let us know.

Write a letter for our Short Reads section, join the debate via Twitter or Facebook or just drop us a line at team@liverpolitan.co.uk

How should we be governed? Six parties have their say…

The Council’s public consultation on future governance models for Liverpool is now open and at Liverpolitan we think you should get involved. But what’s the position of the parties? We asked six of them – Labour, Liberal Democrats, The Green Party, The Conservatives, The Liberal Party and the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) to write up to 400 words stating which of the three governance models they favour and why.

Liverpolitan

Well, we might not have got the referendum we wanted but the people of Liverpool still have a chance to have their say on how the city is run. The Council’s public consultation on future governance models is now open and at Liverpolitan we think you should get involved.

Healthy democracies require participation and in a city that often sets a high bar on shenanigans, figuring out how to keep our representatives and over-lords in check and on-track seems like a worthwhile way to spend our spring evenings.

So what do you need to do?

Visit https://liverpoolourwayforward.com

Read about the three options on the table, weigh up the pros and cons, talk to your friends and family, have a row about it, and complete the online survey by no later than the 20th June 2022.

The three options presented are:

1) The Mayor and Cabinet model – what we have now

2) The Leader and Cabinet model – what we had previously

3) The Committee model – what we had before the year 2000

Once the results of the consultation are in it’s then up to our councillors to decide how or indeed whether to implement the results. That may leave wiggle-room for all kinds of disagreements but there’s a strong suggestion that parties will attempt to honour the outcome. Any changes that take place will be implemented from the 4th May 2023 at the local elections.

But which models do each of the parties support?

We asked six local political parties – Labour, Liberal Democrats, The Green Party, The Conservatives, The Liberal Party and the Trade Unionist and Socialist Coalition (TUSC) to write up to 400 words stating which of the three governance models they favour and why. Each party either has local councillors in Liverpool now or in the case of the Conservatives and TUSC regularly field candidates in local elections.

Here’s what they had to say.

The Labour Party position

We approached Major Joanne Anderson for comment but did not receive a reply, although in a previous interview on BBC Radio Merseyside she said “I want to say neutral." However, an official party spokesperson gave us this statement:

by a Liverpool Party spokesperson

“The city wide consultation is now open and the Labour Party is committed to listening to what the residents of Liverpool have to say about how the City Council is run. It is important that no political party pre-judges the outcome of the consultation and that residents feel that that their voices are being heard. Based on the results of the consultation, the Labour Party will then take a formal position on the governance of our city.”

Model favoured: Undecided

Liverpolitan says: Labour’s position is not to have a position until the results of the consultation are in. They will then decide on their favoured model ‘based on the results’.

The Liberal Democrat position

by Councillor Richard Kemp, Leader, Liverpool Liberal Democrats

The ‘committee system’ is the Lib Dem choice for Liverpool’s governance

“There are three choices allowed in law by which the council can govern itself although some modifications can be made to the Leader and Committee models.

“I am working on the assumption that few in Liverpool would be mad enough to vote to keep the Mayoral system as it has been so badly devalued by Joe Anderson.

“The Leader and Cabinet model has many of the bad mechanisms that are contained in the Mayoral model. Much has been made of the fact that this is the model that the Lib Dems introduced in 2000 but we had little choice because the only two options that were available to us were the Mayoral or Leader models. Both of them concentrate power in the hands of a few people and do so in a way which encourages secrecy and makes it very difficult to challenge what the Cabinet wants to do. The Leader model was the least bad option!

“Since 2012, a third way has been available which is called the Committee system. This means that decisions are taken not by a one-party cabinet but by a number of committees which are representative of the political make-up of the council. That means that:

1. Decisions can be challenged at the time they are made by members of both the biggest party and the other parties on the council.

2. All councillors will be involved in decision making which means that they will know more about what is going on and have to account for the decisions that they make to the people.

3. The people of Liverpool will be more involved as well because there are far more people that they can ‘nobble’ about these decisions.

4. The system is much more accountable and transparent with far fewer decisions being made in the dark recesses of the council.

“We believe that this is the best way forward and will campaign for it in the coming months. However, there is no point in consulting with the people of Liverpool unless we are prepared to debate the issues with them and take heed of what they have to say. We hope that a clear expression of what people want will come out of the consultation. We will then support the people’s views and I challenge the other parties to do exactly the same.”

Model favoured: The Committee system

Liverpolitan says: The Lib Dem’s position is clear – they will be campaigning in favour of a Committee structure of governance but promise to abide by the results of the consultation.

The Green Party position

by Councillor Tom Crone, Leader, Liverpool Green Party

Democratic decision-making for a cooperative political culture

“We are very critical of this consultation. Once again, the people of Liverpool are being denied a proper say on how we are governed. In 2012, while voters in cities across the country were asked if they wanted an elected mayor, Liverpool Labour decided they knew best and imposed the mayoral model. The result was a decade of chaotic mismanagement. Now the city council is having to work round the clock trying to fix the mess left behind.

“This consultation does not have the same democratic authority as a referendum. Having three options makes a clear, unambiguous decision unlikely. The responses will need interpreting, and that will still leave the final decision with the Labour Party. That has a nasty whiff about it. We would much prefer to trust the people of Liverpool with the final decision.

“The Greens will be making the case for adopting the committee system. The committee system involves many more councillors in decision making and policy development. Under the current system even most Labour councillors have very little to do with real decision making. It is only Cabinet members who have real executive powers. Other democratically elected councillors are simply shut out. Even within the Cabinet, the Mayor sets the agenda and can predetermine outcomes. Power is really concentrated in a very small number of individuals. This leads to poor decision making, not least because it fails to make use of the skills and experiences of all the 90 councillors elected to represent their communities.

“The committee system, as well as sharing out power more fairly, also encourages much more constructive cross party working. The public rightly complains about “yah-boo” politics and it is shocking how often our debates in council chamber descend into pointless political point-scoring because really decisions are taken elsewhere. A committee system means different parties having to sit down together and really decide how best to deliver for the people of Liverpool. Councillors will soon realise that they agree on a lot, while learning to respect distinctive perspectives.

“The imposed Mayoral system opened the door to the shame of the Joe Anderson years, and slammed it shut on transparency and democratic accountability. It’s time to ditch the personality politics and let the people back in.”

Model favoured: The Committee model

Liverpolitan says: The Green Party’s position is clear – they will be ‘making the case’ for a Committee structure of governance.

The Conservative Party position

by Dr David Jeffery, Chairman, Liverpool Conservatives

The voters should decide whether we have a Mayor, not Liverpool Labour

“In 2012, referendums were held across 11 of England’s large cities on whether to introduce directly elected mayors. One city was conspicuous by its absence: Liverpool. Instead, in their infinite wisdom, the Labour-run city council decided to ignore the people and voted to bypass a referendum. They introduced the mayoral position by stealth, and parachuted in Joe Anderson – and we all know how that turned out. Of the three authorities which have adopted and then subsequently abolished the mayoral system, all three have done so following a referendum. If Liverpool Labour get their way, once again one city will be conspicuous by its absence: Liverpool.

“The truth is that this Labour council want to ignore voters. This consultation is a gimmick – the result is a foregone conclusion, likely designed to sooth internal party arguments and resentments that have built up under Joe Anderson. We’re told by Labour that a referendum would be too expensive - never mind the fact that seven Labour councillors rebelled over Labour’s budget, which built up excessive financial reserves – but those more sceptical than I might argue it’s not a surprise that this move came after Labour were forced into a humiliating second round of voting in the 2021 mayoral election.

“Decisions on how our city is run should not be made from on high in Labour Party backrooms. Our executive arrangements should not be a consequence of internal Labour Party management. This city’s government is not their plaything, and to treat it as such is an insult to voters.

“There are good arguments for a Mayor: studies have shown that, compared to a council leader, mayors better represent the whole city, are more outward-looking, and are better at bringing much-needed investment into the city. Mayors are put in office by the people, whilst council leaders are selected in grubby back-room deals within their own party, and as such mayors have a better claim to speak for the city as a whole.

“Indeed, it is arguable that the real issues with Liverpool’s politics isn’t the mayoral system, but the fact that Liverpool Labour allowed Joe Anderson to abolish the mayoral scrutiny committee because he didn’t like the type of scrutiny he was receiving.

“Liverpool Labour should do the right thing and give the people of Liverpool a vote on how they are governed. It really is that simple.”

Model favoured: Undecided

Liverpolitan says: The Conservative Party have yet to take a formal position but do see merits in the Mayoral system. However, they believe that it should be up to the voters, not parties to decide which model to choose through the implementation of a referendum.

The Liberal Party position

by Councillor Steve Radford, Leader, The Liberal Party

Time to wake up. Keep the Mayor, adopt Proportional Representation and ask questions

“In over 40 years in politics I’ve seen corruption and abuse of power in all models of local government in Liverpool.

“In the Militant years I saw the sale of land at knock-down prices, council officers withholding information, dodgy minutes and record keeping and much more that I sadly can’t put into print. And that was under the committee system.